A Duel on the Hustings

In August 1833, Grey and his ministry were still enjoying the comfort of the full support of the commons, and a smooth administration. The prime minister, who had occupied his position near-continuously since 1830, was known by now as a great reformer, having been the architect of the passing of the – somewhat aptly nicknamed – Great Reform Bill only the year before. The great Whig engine of reform had, however, slowed by the later summer. Over a year had passed since Grey's triumph, and it was beginning to look like, exhausted by their monumental victory – having extended the franchise by 60% and swept away the last archaic vestiges of electoral corruption – the Whigs were becoming increasingly conservative. With Grey himself, this much may have been true. An awareness that William was growing ever more against reform, and an apparent shift in his own personal views, had seen the prime minister shift noticeably towards the blue end of the political spectrum. This didn't mean he was completely done, however.

Am I not a Man?

Abolitionism had long been prevalent in Britain by the time Grey entered office. Since the time of the French Revolution, members of high and fashionable society had advocated the rights of the black slave. Indeed, Wedgewood's famous "Am I Not a Man And a Brother?" plate served[1] as a very prominent reminder of the fact. Equally, slave rebellions had been as common in the colonies as corpulent, sweating, inappropriately dressed members of the plantocracy growing ever richer from their cash crops. Never, though, had the two sentiments come together as effectively as during the short period known as the Baptist War.

In late 1831 – in political terms, aeons before Grey's reforms had been passed – stirrings in the West Indies, in particular, Jamaica, grew stronger. It had long been the case that 'native' (for, in truth, slaves were no more native to the colonies than you or I) preachers were given some sense of autonomy – notably as far as religious doctrine was concerned. The prevalent denomination amongst the slaves were the Baptists (who differ notably from the denominations practised by those back in metropolitan Britain in that greater doctrinal significance is placed on John the Baptist when compared with Jesus Christ) who, thanks to religious autonomy, were able to run their own chapels and appoint their own pastors and deacons – usually educated slaves, though one would find the occasional white missionary.

One such deacon was Samuel Sharpe, a black 'native' who had been allowed an education, and was therefore respected amongst his fellow slaves. Sharpe had long held the belief that emancipation was nigh. As with many other educated slaves, he was attuned to the abolitionist movements in London, and had full faith in the fact that King William would free all slaves in the colonies. Indeed, when Sharpe's deacon – a white missionary by the name of Thomas Burchell – returned from Britain after his Christmas holiday, Sharpe believed that he had returned with emancipation papers. Believing himself to be a free man, he organised a simple general strike aimed at crippling the rich plantation owners during the integral sugar harvest period. Many responded, and on Christmas Day 1831, slaves across Jamaica put down their tools.

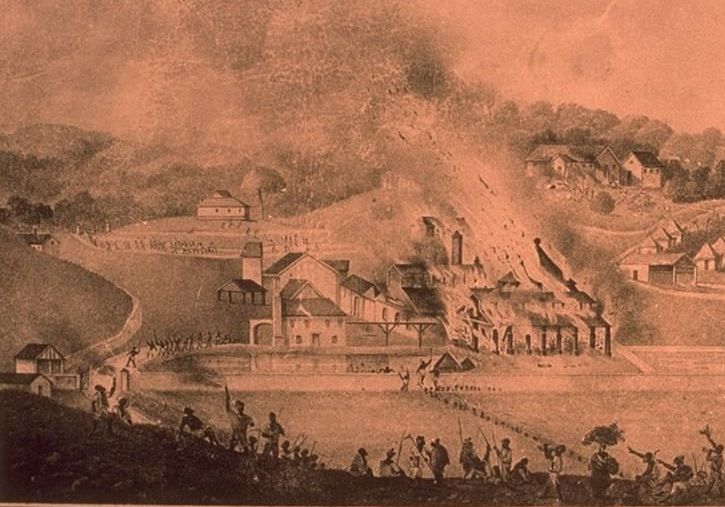

As an educated reader, I'm sure I do not, therefore, need to tell you that 'simple' strike was nothing of the sort. It is a general rule in societies functioning via capitalist structures that owners do not like their workers striking. The plantocracy of Jamaica were no exception. Plantation owners struck back at the slaves, who in turn burnt crops. Within hours, Sharpe's strike had turned into an all out war.

A sketch depicting Samuel Sharpe.

The Baptist War – named after the preachers who first organised the peaceful strike – lasted for the ten days between Christmas Day 1831 and the 4th January 1832. For this reason, and, indeed, due to the less than 'warlike' nature of the conflict, the affair is sometimes also known as the Christmas Rebellion. Rebellion is certainly a more accurate term, as, like so many others of the so-called wars that would erupt and then fizzle out after about a week, very little actual fighting – that is, as defined by the standards of the day; two more or less equally equipped sides fighting an honourable battle of tactical skill – occurred. Indeed, where conflict arose, neither were they equal nor honourable. In the ten days of fighting, only fourteen of the British garrison – under the command of the marvellously named Sir Willoughby Cotton –were killed, compared with over two-hundred slaves. Neither of these figures are particularly Earth-shattering, especially when it is taken into account that around sixty-thousand slaves rebelled, yet they serve to highlight the brutality with which 'native' rebellions were suppressed. The British Army were however, when compared to the plantocrats themselves, tame. On top of the two-hundred or so slaves killed during the actual fighting, anywhere between three-hundred and ten and three-hundred and forty further 'natives' fell victim to judicial executions, apparently taking varied and unorthodox forms. The threshold for execution was lowered, too – one man was executed for the theft of a pig; another, a cow.

This is not to say, nonetheless, that the members of the plantocracy were not at least somewhat justified in their actions – after all, it must be noted that what was initially a peaceful strike had completely ruined the lucrative sugar harvest, while the total value of property damage by slaves is estimated at around £1,150,000[2]. Despite this, even those at the time thought the colonials' actions somewhat extreme. Later that year, two parliamentary inquiries were conducted, the findings of which would contribute to Grey's last great hurrah: the abolition of slavery.

The destruction of an estate during the Baptist War.

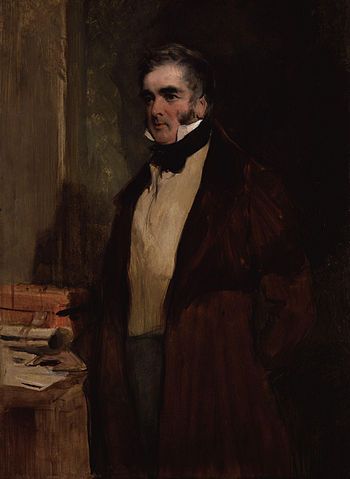

The Abolition of Slavery Act of 1833 was not nearly as contentious and controversial as Grey's last great reform. Whereas the Reform Bill took three separate parliaments to see it pass, the abolition of slavery, it seemed, was a more universally accepted. Indeed, twice before had parliament voted in favour of anti-slave trade laws – first in 1807 during the Ministry of All the Talents, and again in 1824, during the Tory Liverpool administration – and the idea of abolitionism had been popular for decades. There was even legal precedent: Lord Mansfield's ruling in the famous

Somerset v Stewart case suggested that any slave to set foot on British soil is no longer a slave. He went on to say that "the state of slavery is of such a nature that it is incapable of being introduced on any reasons, moral or political". The Abolition of Slavery Act received Royal Assent on the 28th August 1833.

William Murray, the Earl of Mansfield.

A Great Man in His Time

Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey resigned from all political offices on the 16th July 1834. He had been prime minister for nearly four years, and his ministry – having survived Absolutist threats and general elections galore – was notable for its passing of two great reforms; that of the electoral system, and the abolition of slavery. It was for these feats that Grey would primarily be remembered – as a great reformer. Indeed, it was this aspect of his political nature that saw him move increasingly towards the blue end of the spectrum, wary of alienating a king who was, at best, only a moderate supporter of reform. In his later years, Grey grew into a true conservative statesman, arguing in September 1834 at the Grey Festival organised in his honour that further reform should be "according to the increased intelligence of the people, and the necessities of the times". He would go into a quiet, contented retirement at his estate, Howick, spending time with his dogs, his books, his family and criticising his successor – Viscount Melbourne – for associating with the 'radical' Daniel O'Connell.

The Resulting Duel

With Grey's departure from politics, the Whigs were left leaderless, and the country was left without a prime minister. The duty of appointing Grey's successor fell to William, who needed to pick a man acceptable to both himself and the Whig party at large – still the largest faction in the Commons. William decided on Grey's former Home Secretary William Lamb, the 2nd Viscount Melbourne. Lamb had been in politics for nearly twenty years, and was a noted centrist who favoured finding the middle ground, having worked with Canning and Goderich as well as Grey. Though he had largely remained relatively unknown whilst serving in the various cabinets[3], he was known as a competent administrator – notably being praised for his anti-alarmist handling of the Swing Riots of 1831.

Despite this, Melbourne hesitated greatly before taking up the position. He did not like the idea of the extra work brought on by the office of premier, but did not want to let his friends or his party down by refusing both Grey (who agreed with William that Melbourne would be a good man to allow to try and form a government) and the king. It is often said that it was his secretary, a man by the name of Tom Young, who finally convinced him, saying "Why, damn it all, such a position was never held by any Greek or Roman: and if it only lasts three months, it will be worth while to have been Prime Minister of England[4]". This convinced Melbourne, who accepted the king's offer readily and formed a government.

William Lamb, the Viscount Melbourne.

But, as is the perennial theme of British politics, it was not so easy. William continued to oppose the Whigs' reforming ways, and, despite the fact that Melbourne was yet to actually reform anything, dismissed him in November, directly going against the will of the people. The leader of the Tories in the Commons, Sir Robert Peel – famous for having shaped the modern police force in the United Kingdom – was charged with the job of taking over and trying to form a government, the Duke of Wellington having already declined. Peel he was in Italy at the time of Melbourne's dismissal, and Wellington, leader of the Tories in the Lords, was therefore asked to form a caretaker government. The ministry lasted for three weeks, and passed without note. Peel returned in December and took over the running of the government from Wellington, who was allowed to remain as Secretary of Foreign Affairs. In returning to office, the new prime minister wished to distance himself from the "old Tories" such as Wellington and Knatchbull, publishing the so-called "Tamworth Manifesto", in which he accepts the Reform Act of 1832 and announces that he would pursue reform where grievances had arisen. Also notable is the fact that the Manifesto saw the Tory party officially become the Conservative party – a new, altogether more moderate representation of the United Kingdom's right wing. With his new Conservatives (still colloquially referred to as "Tories"[5])

Sir Robert Peel, Bt.

Despite this, parliament was dissolved on the 29th, and elections were scheduled for January and February. The 1835 elections would be the first in the country for three years – a comparatively long time when compared to the three-in-three period of 1830-1832. Going into the hustings with a chip on his shoulder after his dismissal, Melbourne was keen to prove that the popular vote was still with the Whigs. Peel, on the other hand, was keen to increase his share of the Commons and try to break away from the accursed prospect of a minority government. Also notable was the fact that 1835 saw the new Conservative party contest an election for the first time. Daniel O'Connell of the Irish Repeal Party had by this time ceased contesting elections as leader of a separate party, and had instead joined with Melbourne and his Whigs in the hope of stopping Peel from obtaining a larger slice of the legislative cake. Battle lines were drawn, and the two parties each went on their respective campaign trails with much to prove.

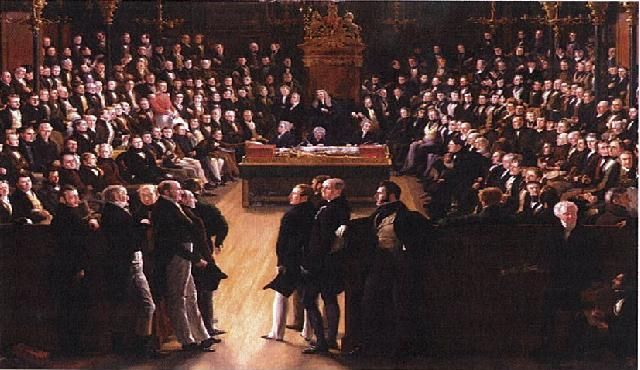

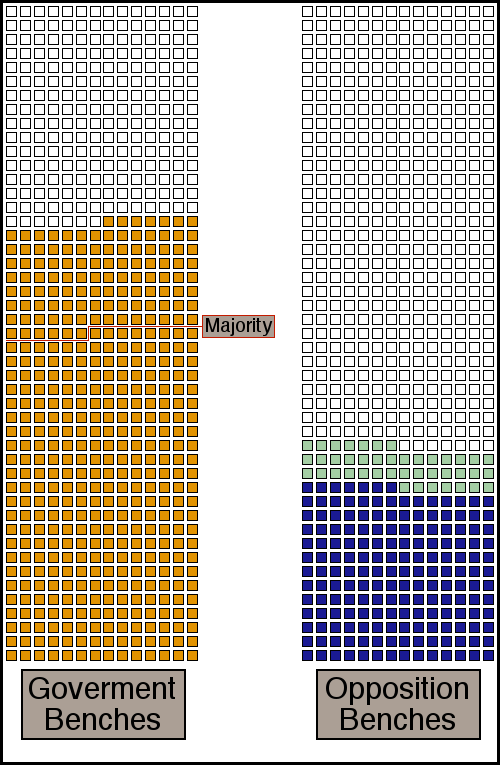

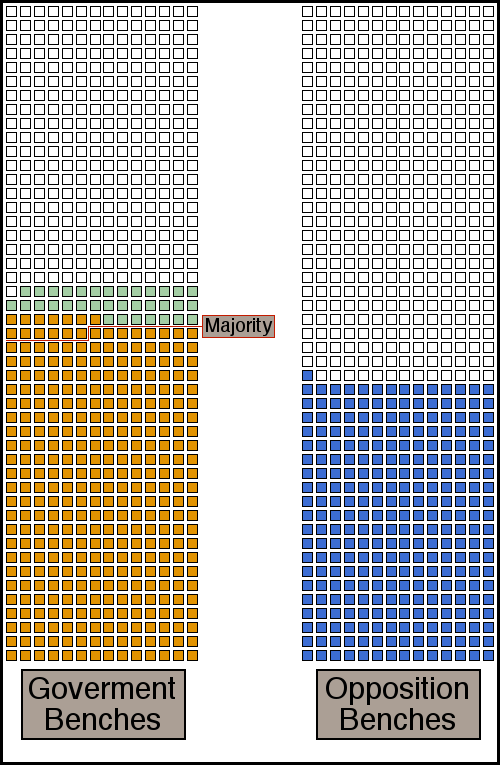

Voting was scheduled for the month-long period between the 6th January and the 6th February, with each constituency (excepting Orkney and Shetland and the University constituencies) having declared by the 27th January. With three-hundred and seventy seats, Melbourne's Whigs had managed to hold onto their majority in the Commons, though went into the next parliament with a reduction in seats of nearly ten per cent. Peel, meanwhile, had managed to increase his standing in the Commons considerably, winning two-hundred and eighty-one seats – a swing of over thirteen per cent. Neither man, however, was to get the result he desired.

The 12th Parliament of the United Kingdom.

In spite of the Whigs' outright majority, Peel was given the chance to form a minority government, which he accepted. Melbourne, however, was not prepared to sit back idly and let this state of affairs continue to pass. He renewed his alliance with Daniel O'Connell, creating an alliance against any bills deemed unsavoury by the Whigs. He was successful, defeating Peel on many occasions. Indeed, Peel's ministry were only really successful in carrying out their promised reforms in the Church of England. Frustrated by a lack of progress, Peel resigned on the 8th April 1835. William had no choice but to cede to the will of the public, and Melbourne was reinstated as prime minister.

1: No pun intended.

2: About £52,000,000 today.

3: He had, however, achieved a degree of fame in 1812 when his wife, Lady Caroline Ponsonby, had a very public affair with Lord Byron.

4: Sic. Naturally, he means the United Kingdom.

5: From this point onwards, any reference to the Tories will be with regards to the Conservatives unless context implies otherwise. Toryism, meanwhile will refer to the absolutist principles of the old Tory party.

), so, this is very intresting for me, and of course well written.