"Poor Estados Unidos; so far from God, yet so close to the Empire of Mexico" - Porfirio Diáz

Table of Contents:

Antonio López de Santa Anna

Part One: Republic

A Note from the Author

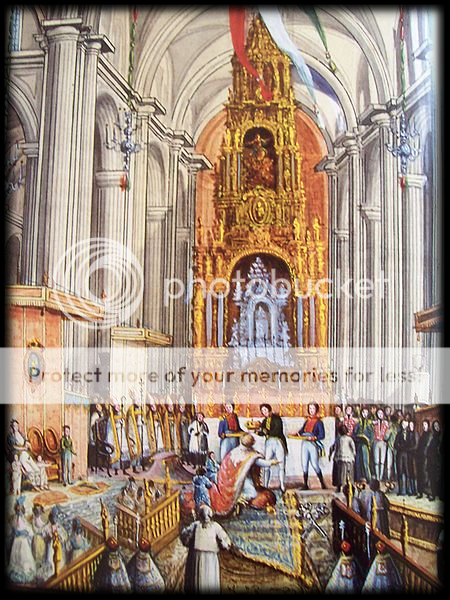

Prologue: From Empire to Republic

Prologue: The Limits of Federalism

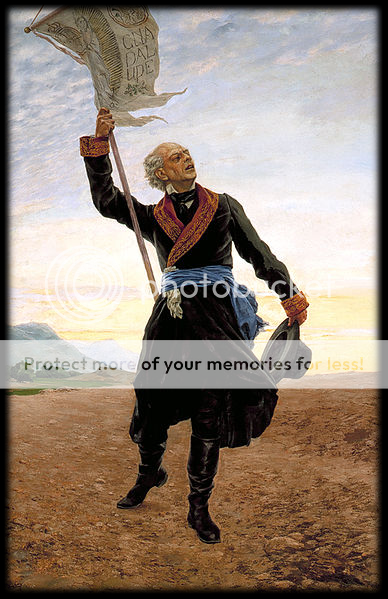

Cometh the Hour Cometh the Man

Of Hubris and Nemesis

Last edited: