French Exploration and Colonization, from 1500 to 1550

Part Two: Colonization

Exploration part 2

Simon de Saint Omer's promotion led to a new form of French colonization. While France maintained small trading posts and military bases in Canada and Greenland before 1524, these bases rarely housed more than 50 people in them at a time. The new French colonization led to a totally different form of settlement, a totally different economic system in the colonies, and a totally different relationship between the French colonists and the Indians*. The first French colony, Louisville, was set up in 1525.

The first French colony, Louisville. 'New World Claimed' is a malus given to Catholics in the early game if the Spaniards and Portuguese manage to get a Pope-sponsored monopoly over the New world

Louisville was originally seen as

the gateway for France to the New World: a half-way home for the ships en route to Canada. But within 10 years of its establishment, Louisville was already obsolete. Louisville was obsolete for two reasons:

-Her unforgiving climate made her uniquely poor as a half-way home. She was not a warm-water port, which led to the loss of several ships trying to return from Canada. Furthermore it would take centuries before the French would have developed the building techniques to deal with the acute cold of the Arctic.

-The long-range fishing ships which Louisville had been home to through the 1510s and 1500s were able to make a cross-Atlantic trip on their own.

The Herring Buss, a Flemish invention, was a long-coming technological advance past the age-old Viking Longship. It came out of financial necessity--namely a need to exploit their predominance over the Northern Atlantic. Busses would depart from Finistere and be out in sea for months at a time, only returning in the Fall, filled to the brim with fish--a trip thought impossible until 1520. Simon de Saint Omer already saw a great deal of potential in the ships: if the French could transverse the whole Atlantic in one go, then the colonization of the Americas could begin in earnest. But it wasn't until 1526 that such a voyage was tried, but in 1528 a buss containing 100 settlers landed on the island of Unamalik, the soon-to-be settlement of Villenueve.

The fortress of Villenueve

Now I will split up the discussion of early French colonization into 3 different topics--trade, French-native relations, and religion.

Trade in the French Colonies

As I said, fishing was the main trade good of the French colonies during early exploration, and this remained the case until nearly 1600. The massive fishing areas of the Northern Atlantic allowed for a massive haul, to the degree that the design of the Flemish buss was held as a state secret for 2 decades before the English found a beached one in northern Scotland. Fishing was a fantastic market--it required little to no contact with the Indians, it was a food resource, and it was easily smoked and salted and sold across Europe. French smoked salmon became a Europe-wide delicacy through the early 16th century, and these funds were plowed back into the French commercial marine, which became one of the most innovative in the world, alongside the English and Portuguese.

But with the French settling of the Canadian coast came new trading goods, goods which relied on positive Franco-Indian relations. These goods were primarily 'military' goods, used to increase France's military capacity, but they soon became important in a colonial context. The dense forests of Sangueway became one of the largest sources of wood for French capital ships starting in 1560, but combined with Indian knowledge the elk wood led to a mass production of canoes and kayaks, which were by far the best way to travel across Canada until the 19th century. The copper mines of Kespek gave both copper which was sent east to be turned into cannon in France, but starting in 1540 was also used to arm the local Indian tribes.

A depiction of urbanized fur traders, dated 1777. It was only in the 18th century that fur trading would become an urban venture, until then it was primarily the work of French frontiersmen who rarely saw 'civilization

But it was furs that became the primary good of Canada. Furs were to Canada what cotton was to the American South; just as cotton, a highly breathable cloth, became key to English survival in the hot climate of the South, furs, which provided much needed warmth, were key to French survival in the North. Eventually furs would become not only the main clothing of the French military in Canada, but would become a fashionable clothing item in and of itself.

French-Indian Relations

The transition to copper, furs, and logging as resources required a huge about-face from France's earlier Indian Policy. De Saint Omer saw the Indians as a potential threat, a de Villenuevan 'variable' which had to be controlled. This was possible in the settlements of Louisville and Villenueve, where the tribes were relatively small and unconnected to larger Indian nations. But the native American tribes remained the largest military force in the Americas until the 18th century, and once France moved out of the islands on the coast and started dealing with the tribes on the mainland, it became clear that she would have to take a more diplomatic approach. This led to the rise of one of France's greatest ambassadors, alongside d'Ursine in greatness. Firmin d'Estrees was one of the first generation born in French Canada, and he knew the language of the Huron and Mikmack tribes. His first negotiation occurred at the age of 16, when he was sent on his own from Villenueve to the tribes of Kespeck armed only with a brace of pistols and carrying a bag of shells and steel knives. The plan was to have him negotiate for mining rights for the French with these items alone.

When he met the tribal leader, he was taken aback. The Indians, who had a far better diet than the colonial Frenchmen, were on average a foot taller than the Canadiens, but the chief Hassun was by all records taller than 6'7". Moreover it seems that he had learned how to read from earlier French expeditions. D'Estrees came expecting that Hassun would ask for more materials (perhaps rifles), but was surprised when he communicated the French want to mine in the hills of Kespek. Hassun responded that he wanted two things: a treaty with the French saying that they wouldn't move troops onto the mainland, and to be converted to Catholicism. At the request of Hassun, d'Estrees baptized the whole Mikmak tribe (

This is a historical event! Although it was a Huron tribe which asked to be converted, and Cartier who was like 'oh yeah'...and didn't. Because Cartier was a dick.), and agreed that the French would ship Bibles to the tribe within the year's end. This was the beginning of generally positive French-Indian relations

A drawing of the Indians teaching French scouts how to use canoes to go across Lake Flanders

Religion in Canada, 1500-1550

Religion in early French Canada is a spotty subject. Unlike, say, the Spaniards, who explicitly colonized South America as a missionary act, the French saw Canada as a military holding, and it wasn't until very late that Canada had its own missionaries. This is odd considering that France was the center of Catholicism through the 16th century, producing most of the religion's monks as well as the Society of Jesu in the 1580s. But in some ways a lack of religiosity helped the Canadian colony greatly in the early 16th century. The French frontiersman, as a 'type' was a man who lived off the Indian tribes, who rarely saw the metropole. An ability to communicate with the Indians on their terms was the mainstay of the frontiersman's way of life, and indeed the key social trend in French Canada in until the 17th century was an integration with the Indians rather than the other way around.

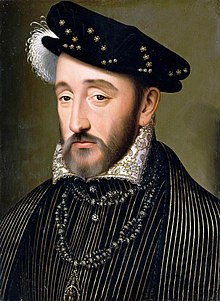

This aroused horror in the French. Henri II considered a policy of separation of the French from the Indians, only convinced by the junior diplomat d'Estrees not to do so at the last minute (

Note: segregation between the French and Indians happened historically, which really weakened the urbanization of Canada). D'Estrees knew from experience that the Indians were open to conversion to French culture and religion, but that doing so required a great deal more tact than say, the Spaniard missionaries.

Instead, French missionary efforts came out of the old French monastic strategy of attaining faith through education and criticism. D'Estrees's first act in the French court was to try to convince Robert de Bosquet to allow monastic orders into the colonies. The Monastic orders, seen as an internationalistic and possibly destabilizing force, weren't allowed into Canada in the early 16th century. The first group of monks, a Franciscan order under Henri de Rouchlet, came to Villenueve in 1550. With this step, Canada had started along the path from frontier to colony.

Canada and the French Court in 1548, soon before the death of Henri II

*Although I don't like the term 'Indian', it was the term that contemporaries used so I guess I'll stick with it.