Lords of France

Consolidation part 2: Successes ch1

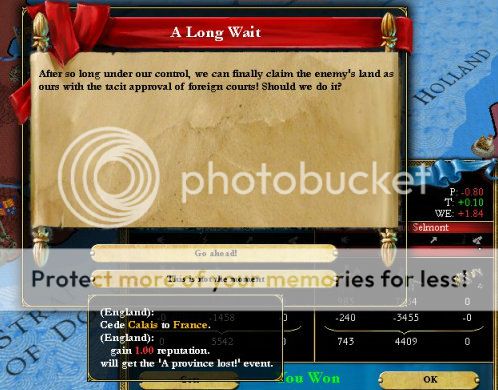

Although chaotic, the transitory period of the 1460s resulted in multiple gains for the French crown. The nature of these successes were different, arising from the divided nature of the French government at Charles VII's death: de Villenueve and d'Ursine, hired by Charles and deeply influenced by his nature, clashed with Francois multiple times, which essentially delegated Francois to domestic matters until d'Ursine's death in the later 1460s. So we have the occasional successes of the Crown acting on its own, and the occasional successes of the Counseil on its own. Occasionally, however, the goals of the two bodies would coincide and lead to a great diplomatic or domestic victory: I will deal with those successes first.

On Command and the annexation of Orleans

Portrait of Armand de Villenueve by the Dutch painter Roger van der Weyden, likely commissioned during de Villenueve's time as the commander of an Italian mercenary regiment

De Villenueve could arguably be called France's greatest marshal: with the exceptions of some of the generals of the Revolutionary Wars, his were the greatest singular achievements (an invasion across the Channel, the end of the 100 Years War). Further, he committed to several major top-down reforms (the Levy Reforms), introduced cannon into the French armies, and last but not least, he cowrote one of the first great books on the subject of war, known a

On Command. The writing of

On Command, though, was more than an intellectual or even purely military achievement: it facilitated the annexation of the strategically crucial Duchy of Orleans.

Map showing the location of the Duchy of Orleans, located a week's ride from Paris

However, before I discuss the annexation of Orleans, I feel that I should discuss first the imposing figure that is Armand de Villenueve, and secondly the kind of strategy he argues for in

On Command, because it very much explains the unheard-of aggressive strategy that the French crown took with regards to her vassals and enemies.

Armand de Villenueve was born in the province of Dauphin, at the southern part of France, bordering the Duchy of Provence. As such, his estate was never threatened by the English, so, like many other Provencals, as a youth he oft wondered what the purpose of loyalty to the French crown was. Many of the Provencals looked to the East, to Italy, as an example of how rich they could be if they separated from the crown and oriented themselves towards Italian trade. De Villenueve was so enamored of Italy that, the moment he turned 15, he took his suit of armor, his horse, his sword, and his Italian manservant Antonio and joined an Italian mercenary brigade.

Through the late 1430s and early 1440s he fought across Italy, serving in the light cavalry of the condottieri Frederico da Montefeltro. But he wasn't only a soldier: during his many leaves he studied the works of Petrarch under the Italian humanists, and became a rather skilled painter under the tutelage of Georgi Santi (the father of Raphael). This humanist training all contributed to de Villenueve's writings in

On Command, which is often compared to

The Prince in terms of its utterly secular viewpoint. It contributed to something else, however: de Villenueve, aided by his already fierce intelligence and his charisma, but also by the connections he fostered within the city of Urbino, became one of the chief officers in the Army da Montefeltro, and led the cavalry in the taking of Urbino by Frederico da Montefeltro. After this he became the general of the newly formed Urbianti army, fighting in wars against the Papacy, the Naepolitans, the Florentines, and the Milanese, and returning successfully from all of them.

A painting of de Villenueve's cavalry brigade, which proved instrumental in bringing Urbino under the control of Frederico da Montefeltro

This gave him a sharp sense of perspective. Fighting against nearly all of Urbino's neighbors led de Villenueve to appreciate the safety and unity brought by a strong government such as the French one, and became a sort of French proto-patriot in a fashion similar to Machiavelli's proto-Italian patriotism. The destruction of the Byzantine Empire by the Turkish army drove de Villenueve even further towards Ile de France: he saw that the bastion of Christianity in the East could not be defended by Italian money or mercenaries. This isn't to say that de Villenueve advocated for a new Crusade: he simply feared that a Europe comprised of weak states would suffer the same fate as the Byzantine Empire: upon hearing the news he left the service of the Duke of Provence*, and began to work in the French army, and in late 1453 he was appointed Marshall of France.

Although Charles was impressed by de Villenueve's record, he feared that his experience as the leader of the 5,000 man Urbianti army wouldn't scale up to leading France's 40,000 man force. However, de Villenueve swiftly showed his competence against the Army of Aquitaine and in the raids against England. He did this alongside Louis D'Orleans, the Duke of Orleans, who was designated the leader of the armies of France's vassals. The two worked together as the collective Commanders in Chief during the last stages of the war. This led to a deep relationship between the two, which led to the first cooperative effort between the Counseil and the new king Francois.

The French court in 1460, after the crowning of King Francois I. Jean des Ursins (also known as D'Ursine, or the Bear) and Armand de Villenueve, acting as the chiefs of the French army and diplomatic corps respectively, dominated French foreign policy during the early 1460s, with Francois I and Ignazio Mancini having slightly more free will domestically

The safety of Paris, it was agreed, was of tantamount importance to the French government: it was the largest center of intellect and commerce in the country, and accounted for ~10% of the realm's taxes. Furthermore, the trade which flowed through the city was now coming in in floods due to the civil war in England and wars going on in Northern Italy: if that safety were to be continued then the French crown could become very rich indeed. This security required that Paris not be accessible by any possible enemies. To help this purpose, de Villenueve was sent to foster his relationship with the Duke of Orleans, and d'Ursine was sent to Burgundy and the Holy Roman Empire to somehow undermine the court in Bourgogne.

De Villenueve took this as the opportunity to do what he had wanted for a decade: to write on his experiences, and create a book which would drive French strategy. In Louis D'Orleans he had found the perfect cowriter: although the two had comparable experiences, Louis D'Orleans had lived a far more educated life than de Villenueve and was the better writer. For the next 2 years, the two wrote a book on the subject of Command, with the Duke of Orleans devoting more and more time to writing the book and less and less time ruling his kingdom.

The level of strategic thinking present in

On Command would not be replaced until Clausewitz. Further, it influenced French strategy making (acting as an ideal for French generals until Frederickan warfare replaced it in the 17th century), so I feel that it is necessary here to provide a short discussion of its argument.

De Villenueve and D'Orleans focus primarily on the character of

Fortuna, the goddess of luck, who they say presents herself in several forms:

"No battlefield is ever alike: any battle will occur in different places, at different times, with different weather, involving different men and fighting with different arms. Even if one were to gather all of the veterans of a battle to the same field, at the same time of day and with the same weather and forced them to fight with the same weapons, they would be different men". With this said, De Villenueve felt that the role of the Commander was to account for these variables as much as possible, while realizing that total control is impossible. How does a commander account for this?

De Villenueve and D'Orleans give three specific methods to deal with the variables of chance: scouting/raiding, a strong logistical and support staff, and a defensive (although aggressive) stance. What does de Villenueve mean by defensive, though aggressive?

His argument is essentially a repeat of Clauswitz' statement, that the Defensive is the stronger form of war: by acting defensively, you are forcing the enemy to go through the vagaries of chance: they must extend their supply lines, attack you on the terrain you decide, and generally wear down their troops. However, de Villenueve isn't arguing for a passive stance towards warfare: instead, he urges for scouting and raiding formations to take advantage of the opponent's lengthened supply lines and make sure that you aren't

force, to the defensive, which diminishes the information advantage one gets from being on the defensive.

The strategic theory forwarded by de Villenueve and d'Orleans argued for and normalized the use of professional and dedicated raiding forces to keep the opponent from benefiting from what would become France's typically defensive strategic posture.

The difference between raiding tactics, which de Villenueve sees as important but not crucial, and the tactics used for an army (as well as the difference between choosing to go on the defensive and being forced on the defensive), is how de Villenueve explains why his defensive strategy brought him to think of an invasion of the British aisles: the English were

forced on the defensive by the destruction of the Army of Aquitaine, and by raiding the English countryside, he kept the English on a forced defensive while giving him intel on any expansion of English forces, which led to France's eventual grand victory and the end of the War.

This difference between forced and planned defensives is what brought D'Orleans to see the logic of annexation. D'Orleans, related to Francois I by blood, had always been the Kingdom's greatest advocate in the Estates. He'd served within the French government and army, and had helped implement and make policy when the King needed him. However, by 1461, he was an aged, childless man. The Duke of Provence, relying on an old French law, pressed to have D'Orleans succeeded by a man agreed upon by the estates. De Villenueve had, by this point, befriended the Duke, and through his friendship, started arguing for the French crown.

Over the 1450s and 60s, de Villenueve impressed upon D'Orleans the feelings of the Conseil on the security of Ile de France. Furthermore, as D'Orleans and de Villenueve became closer, de Villenueve revealed some higher level state intelligence: the Duke of Provence was planning a revolt. Now, it wasn't a plausibility just yet--the Duke was looking for possible allies--but if he had Orleans in his hand he would be able to take Ile de France before the French army would be able to react to the attack. With this information, the Duke of Orleans had made his decision: on his death, he would bequeath the Duchy of Orleans to the French crown.

And so,

On Command was one of those rare books which impacted political, military, and intellectual history. It impacted French strategic thinking for more than a century and it resulted in the annexation of the Duchy of Orleans. But it had one last effect. The Duke of Orleans had far more than his land to give: he wished that his extensive treasury be dedicated to the creation of an Army Academy which would teach a dedicated Officer corps and a dedicated support staff. This makes perfect sense from the perspective of D'Orleans: he'd been arguing for years now for the importance of a large logistical/support staff, as well as the importance of scouting/raiding operations, operations which, in light of the de Xaintrelles debacle, relied highly on the skill of the commanding general. As such, the French Royal Academy of the Army in Orleans was split into 3 schools: a Cavalry school for Cavalry commanders, a Logistical school (which later included sieges and training for Artillery Officers), and an Infantry school to train Infantry officers. In 1465, Jean Bureau, the Scourge of England, the Great Raider, and the defeater of the Army of Aquitaine, retired and became the second Headmaster of the Academy. He worked to instill the same sense of duty that he felt the Duke of Orleans had, which produced a nobility which, at least, didn't actively hate the French government.

As such, the writing of

On Command left the French Army decades ahead of its enemies theoretically, and left the French government in a very beneficial situation with regards to her vassals.*

The results of the writing of On Command by Louis D'Orleans and Armand de Villenueve: the theoretical advantage that it brought to the French army, the annexation of the Duchy of Orleans, and the creation of the French Royal Academy of the Army, the first Royal Academy

*Can anyone tell that I was reading some Clauswitzan theory on the bus to and from my girlfriend's?