Rome AARisen - a Byzantine AAR

- Thread starter General_BT

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Eleutherios or whatever the spelling.

It rings a bell. Damn this AAR is big, so much characters.

It rings a bell. Damn this AAR is big, so much characters.

This

And BT, Iwant CHAOS. You have denied me too many civil wars in the last few update, I believe this peanut gallery (like the term? a friend of mine reminded me of it) demand blood. Oh and I love the 'theme song'. It is fitting

Sorry I don't have time to make proper comments at the moment, but I thought you all would appreciate another update at the least.

"Κάλλιο να σου βγει το μάτι παρά το όνομα."

"It's better to lose an eye than to get a bad name." – Roman proverb.

June 7th, 1262

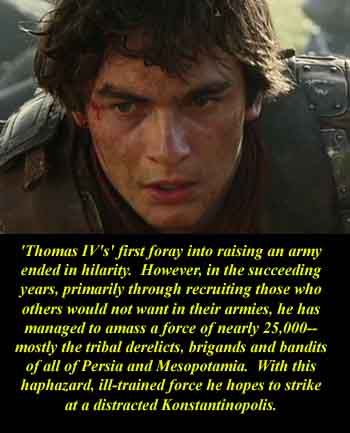

Alexandros Komnenos, Junior Emperor of Persia, glowered at the instrument in his right hand. His face wrinkled up, and for a moment, its dark scowl made him look older than his 30 years. The silver instrument in his hand blandly glinted back, as if mocking its master. It’d been a gift from his wife Šahrzād—that alone would have made him glower.

She’d even commented he’d needed it to learn, “proper manners.”

That was three weeks ago, the last time he’d seen her and son and namesake Alexandros—the boy was five, and surprisingly quiet like his uncle Nikephoros. Alexandros could only barely tolerate that Persian trollop, but he loved his ‘Little Alex’ more than his own life. Being kept from seeing him because of Thomas’ ‘insistence’ that preparations had to be made for his madcap army made Autokrator Alexandros Komnenos an angry man.

An angry man whose furious gaze was directed at the cause of this missing time—his cousin, the self-styled Thomas IV, Emperor of the Romans.

Alexandros was sure his dimwitted cousin had no idea how fortunate he was that the junior Persian Emperor’s mouth was currently filled with mutton. For in Alexandros’ hand was a wondrous invention used by the locals called a fork, and its doubly pointed prongs could just as easily find their way into Thomas’ eye as they could the mutton sitting on the Emperor’s plate.

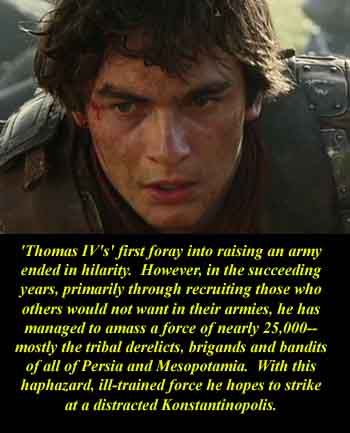

“…and abd-al Nasif also raised 4,500 men from Gilan,” Thomas droned on, detailing the contribution of this ‘noble’ or that ‘elect man.’ Almost all were Muslim, and more than a few were no elites of any regard—the ones Alexandros recognized he knew to be tribal leaders from the mountains of Gilan or Azeribjian, not the leaders of any organized, civilized people. The junior emperor swallowed, and promptly stuffed another piece of mutton into his mouth, before looking over at his elder brother.

Nikephoros Komnenos only folded his arms and gave one of his perpetual sighs.

“That’s 25,000 men,” the senior Persian Emperor nodded. Nikephoros at 32 still looked beefy, hale and hearty, even if he still spoke quietly. Unlike Alexandros, who sat and ate his lunch in silks befitting an emperor, Nikephoros looked, and felt, much more at home in his half-kit armor. Also unlike his younger brother, the elder Emperor was not sitting—he leaned against one of the doorways to the small room.

“125,000, you mean,” Thomas interrupted. “Surely that Spain has erupted, and the Danes are on the move, you’re going to support my claim with your armies?”

Alexandros scowled—Thomas had opened his mouth at a moment when Alexandros’ mouth was not filled with food. Before he could catch his tongue, the junior of Gabriel’s sons spoke.

“No,” he said, stopping angry words from tumbling out. His cousin was daft!

“And why not?” Thomas demanded, hands on his hips like he was wont to do. Alexandros shoved another bit of mutton in his mouth, but at his cousin’s imperious stare, he decided to speak anyway—rude or no.

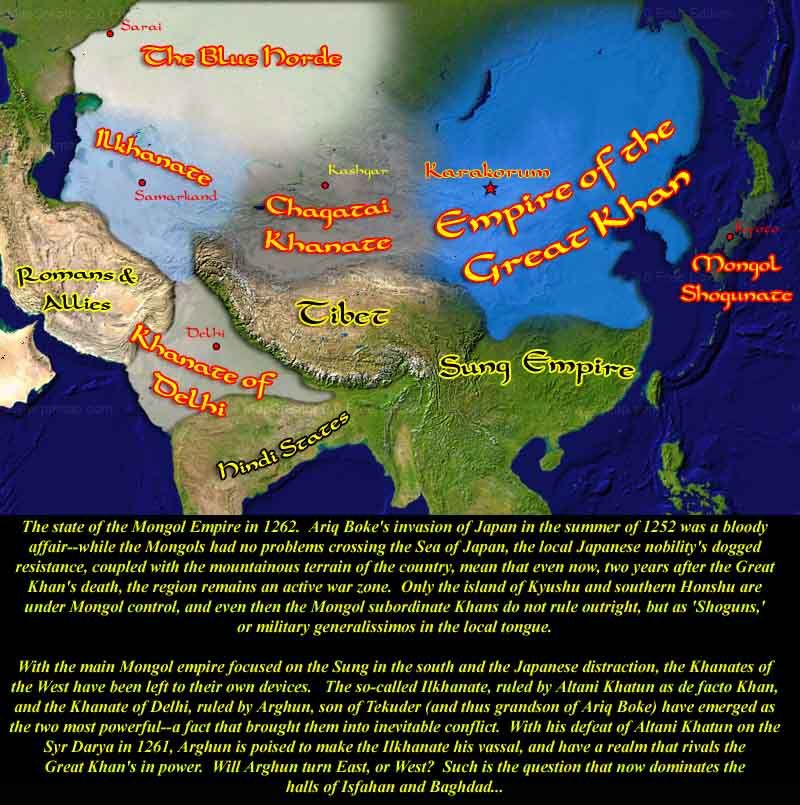

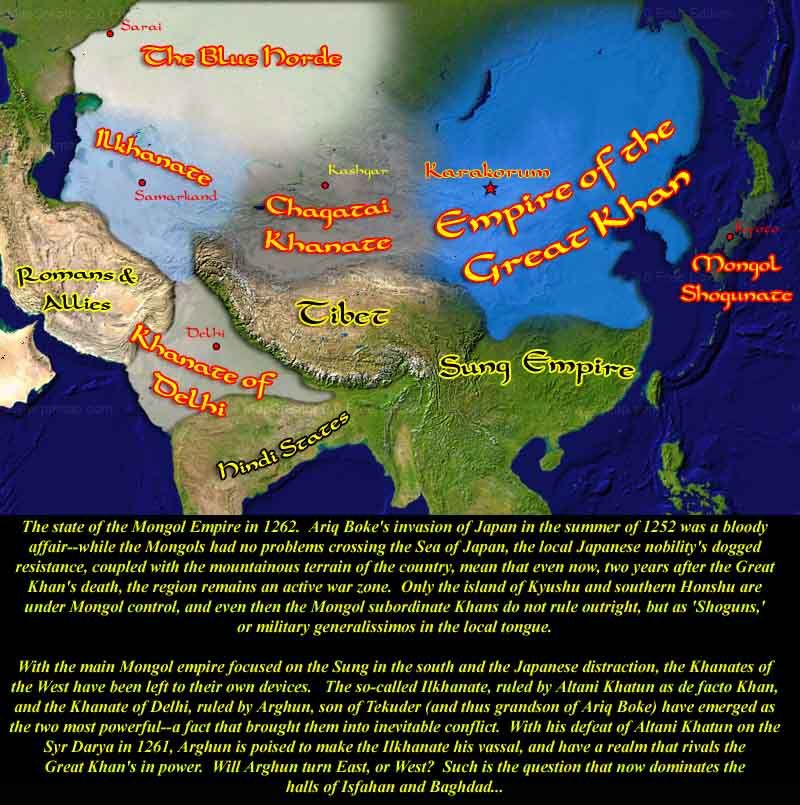

“Arghun Khan has defeated Altani Khatun,” Alexandros muttered once his mouth was cleared of mutton. “Thrice, actually. Took Samarkand and spared the city once she knelt as his vassal.”

“And what does that have to do with my claim to my rightful throne?” Thomas asked dangerously. “Altani Khatun was your father’s enemy, and he bested her! Besides,” Thomas waved his hand dismissively, “she’s in Samarkand! What does that have to do with Romanion?”

“Nothing,” Nikephoros grunted, “and everything.”

“Nothing and… what do you mean?” Thomas frowned, clearly perplexed. Alexandros sighed—his cousin could have always been considered a dullard at best.

“We can’t fully back you without leaving Persia exposed,” Nikephoros explained gently, while Alexandros snorted, stabbing the mutton with his ‘fork’ once more and biting another chunk. The device really was ingenious, he had to admit.

“And if ‘dis Arghun, or Mahmu’th, as he’s now calling hi’thself,” Alexandros waved the fork around as he spoke, “has taken Samarkan’th, he’th now on our bor’ther.” He swallowed. “And if he’s bested Altani, its only a matter of time before he starts looking our way. We aren’t going to leave Persia exposed.”

Alexandros watched as his cousin’s face fell. The stupid boy. He looked over at his brother—Nikephoros shook his head gently. Alexandros stabbed his fork into another piece of mutton and stuffed his face. It kept his mouth shut.

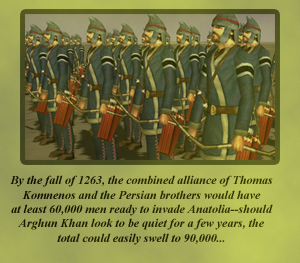

“But,” Nikephoros jumped in before Thomas could lodge a complaint, “we are willing to send three tagmata, plus levies…”

“Three tagmata? Out of thirteen?” Thomas hissed.

“25,000 soldiers,” Nikephoros nodded. “They’ll have barracks in Samarra and Mosul…”

“So they won’t even follow my crusaders across the border?” their cousin complained. “Even if you send those troops, that’d bring my men to 50,000! Imagine what we could do if we went into Anatolia with 50,000! That little brat has his armies in Cherson and Spain! He…”

“…has seven tagmata in his Anatolian army that are untouched!” Alexandros finally snapped. Was Thomas blind, or a fool? Hadn’t he seen the reports? The grain provision numbers that their contacts spoke of? Yes, many of the young whelp’s soldiers went West and North. And those ten didn’t even count the eight in the Reserve Army Asbjorn’s people spoke about! “Do you want us to lurch into a war with an enemy at our back, against superior numbers?!”

“You’ll have my men!” Thomas angrily spat back, on his feet.

“Useless lot they are!” Alexandros was up too, his face inches from his cousins’s. “Tribesmen! Louts! The dregs of mankind! How will those boys with wicker shields and shaky spears stand against mailed skoutatoi!? Idiot!” Alexandros added harshly. As his cousin’s face went ashen and broken, he spat onwards. “Do you think we’re fools that’ll lunge into this with only a codpiece on?”

“What about Georgios Donauri’s?” Thomas shouted onwards.

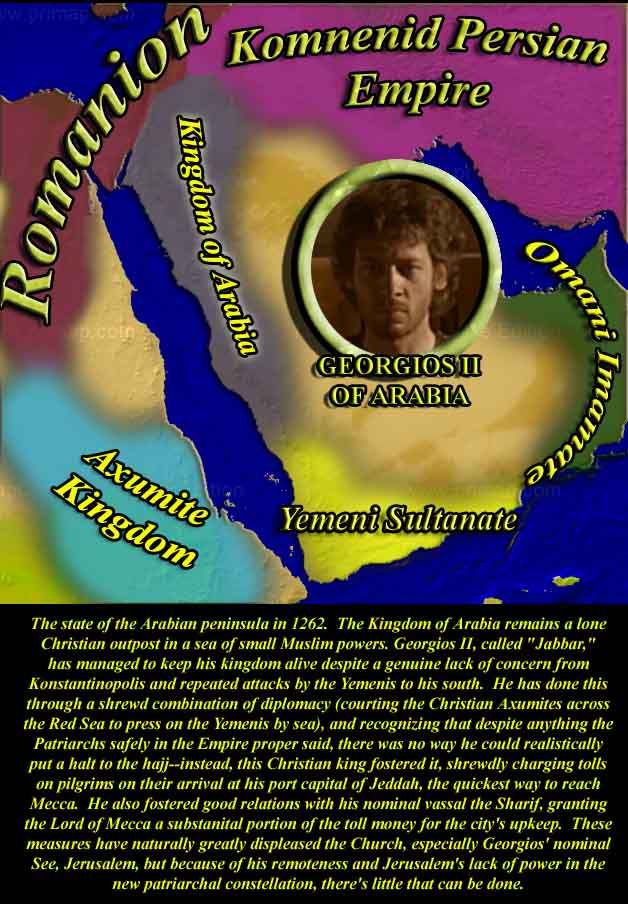

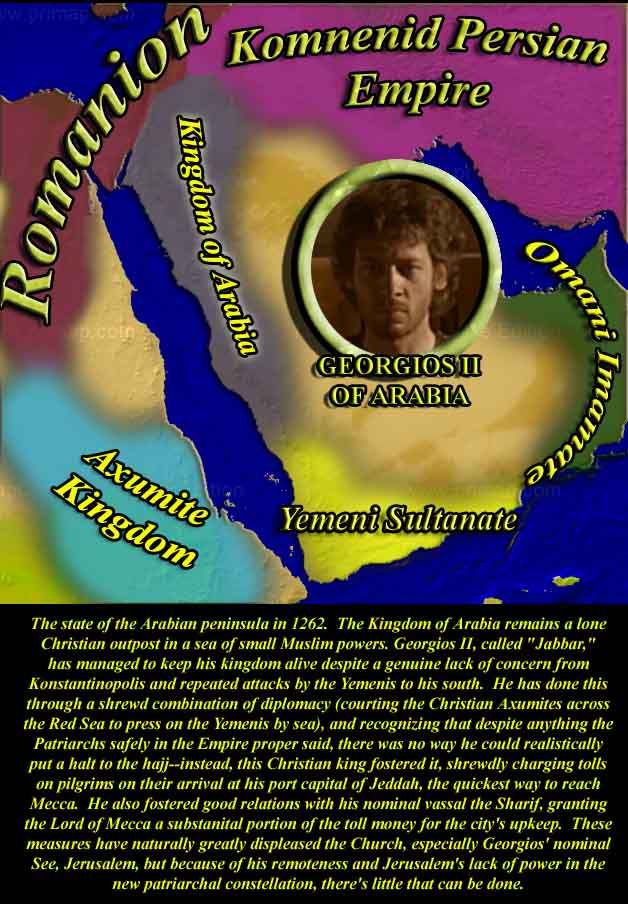

Alexandros cleared his throat—he felt a thick wad of spit on his tongue, and it took all his will to spit at the ground, not at his cousin. “He’s the only man the Church hates more than my father!”

“At least father is still a Christian,” Nikephoros added glumly. “Not a follower of Aionymos or Aionyos…” Alexandros didn’t see his brother’s confused shrug, but he knew it was there. Saying Georgios II Donauri of Arabia had converted to the words of some madman from the desert wasn’t the truth—Georgios took the sacraments and confessed his sins as any good Christian, but the Patriarch of Jerusalem was incensed that the son of the famous strategos of the same name not only let the hajj continue unfettered, but let men like the one calling himself “Timeless One” preach in the streets of Jeddah and Mecca. Already, Alexandros had heard from merchants in Karbala and Najaf that every year, more and more people came to Mecca not for the hajj but to hear the words of this Aionios, as he called himself in Greek. While Alexandros might join the Patriarchs in disapproving of how lenient Georgios had become, he couldn’t fault the man—he and his court were lone Christians in a heathen sea, far more so than even the court in Persia.. Some leniency meant survival, more could be a godsend, as Georgios’ popularity with the people in his Kingdom testified.

“But he said…”

“…an empty promise!” Alexandros cut his cousin off. “He promised you what? 10,000 men?”

“20,000!” Thomas’ jaw jutted forward. Alexandros thought he looked like some proud crane, strutting about moments before a hunter’s arrow struck it down.

“Arabia doesn’t even have 10,000 men, Thomas,” Nikephoros sighed. “Georgios sent you some empty words, so that in the…” Nikephoros stopped suddenly. Alexandros couldn’t help but smile darkly. Nikky always had the more careful tongue, something Alexandros found himself thankful for on more than one occasion.

“…once you won,” Nikephoros said in a deadpan, “he could get you to pressure the Patriarch of Konstantinopolis to call off his Jerusalem hounds.”

For several seconds, Thomas stood, mouth agape, like some twisted oak halfway between standing tall and lurching over to the ground. Finally, a single word escaped his obviously confused lips.

“Oh.”

“Alexandros is right, Thomas,” Nikephoros advanced into the verbal gap, not letting either cousin take advantage of the silence, “you have many eager men, but they aren’t trained, and they aren’t well equipped. Hold your troops just inside the border, outside of Baghdad,” Nikephoros sighed. “Train them, and we can see about equipment,” the eldest brother added, pinching the bridge of his nose. Alexandros frowned—that was a sign his brother was in thought, and the thought he was mulling was something Alexandros might not like…

“You mean…” Alexandros started to interrupt, but Nikephoros simply talked over him.

“Thomas is right too, Alexandros,” the eldest, and thus senior, said quietly. “Now is perhaps the best time we’ll have in decades to do something about Konstantinopolis. Thomas’ men are raw, but given some discipline, even the rawest recruits can gain a spine.” He pinched his nose again. “It will take time… Alexandros, you’re the better captain of the barracks, you should look to his recruits, while I see to their equipment.”

Alexandros started to open his mouth to complain, but he bit off his words before they leaked out. Nikephoros was up to something—he always was up to something. Usually it was clever, and usually it was to Alexandros’ benefit—so the younger brother folded his arms and listened.

“Probably a year?” Nikephoros raised an eyebrow.

“At least,” Alexandros finally huffed. “Most wouldn’t know a kontos if I swung it and hit them in the head. A year might turn them into acceptable light troops. Holding a battleline against skoutatoi?” He pursed his lips and shook his head.

Nikephoros nodded. “Good. A year will give me time to make preparations in the East—calling up some politkoi to watch the frontiers, perhaps shift a few of them and a tagma or two West...” Nikephoros grunted, “…and gauge what is going on with the Mongols. If they look threatening, we can hold some troops back. If they look distracted…” A thin smile finally crossed his normally dour lips.

“However,” the eldest Komnenid present added, looking squarely at Thomas. “Our help will have a price.”

“Name it,” Thomas folded his arms, grinning at Alexandros in triumph.

“My brother and I are co-Emperors to you, equal in rank and authority, of all of Romanion and her dominions,” Nikephoros said simply.

“But, it’s my…”

“Our,” Alexandros glanced momentarily at his brother, before stepping closer to his cousin, “throne, dear cousin. Our throne. Just as our fathers were joint rulers, so shall we be.”

“But…”

“No joint imperial title, no army,” Alexandros crossed his arms. He didn’t need to look at his brother to know he was nodding as well. Nikephoros always came up with the plans—Alexandros wasn’t happy, but he hoped this turned out like his brother’s other schemes…

==========*==========

Battle of Azov

From Sandra Levy-Day’s Fire and Reform: The Last Komnenid Army, University of Cordoba Press, 1984:

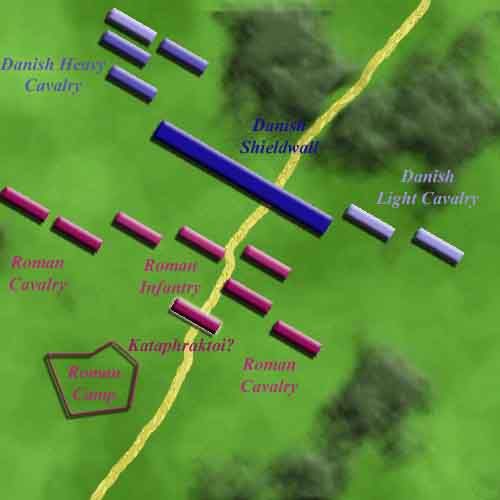

…The Battle of Azov is certainly not remarkable in Roman history for its size—while very large for the standards of its day, the Romans fielded much larger armies elsewhere during the campaigns of 1262-1265. If anything, the one remarkable thing about the Azov campaign was the sheer aggressiveness of Bataczes. Roman tradition on the steppe had called for cautious, even reserved campaigns—every Roman commander facing a foe on the Russian steppe had first lured them away from the steppe—Emperor Manuel towards the Black Sea coast, the Megaloprepis into the Kodori Valley. After his landing in Cherson, however, Isaakios Bataczes did exactly the opposite—after five days of raiding the theme’s stores for weapons and supplies, the Roman commander sailed across the Straits of Kerch to Tmutarakan, then began a frantic march north.

While many have commented that Bataczes did this with inferior numbers as well (some 25,000 versus 50,000 Danes sieging Azov and laying waste to the entire theme), this historian is inclined to remind them that the Roman army was a disciplined, almost wholly tagmata host, compared to the Danish force which had many levies as well as a hardened, veteran core. Thus, the number disparity is deceiving.

A new theory put forward by J.D. Hanson is that Bataczes’ speed came at a price—his army marched with few food stores beyond a limited pack train. This would explain why Bataczes was able to march so quickly, covering 60 miles in three days—and also would explain why the Roman was so eager to do battle, before his men had to fight on empty stomachs, or worse, his force would have to divide to forage.

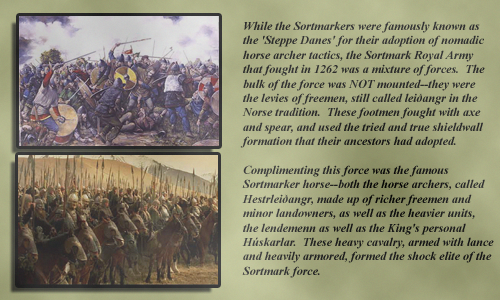

On hearing the news of Bataczes’ landing, King Olaf did not remain idle—the Sortmarker lord left 10,000 men to mind the siege lines, while the bulk of his army, still a handsome 40,000, moved rapidly south to intercept. The Sortmarkers were enthusiastic that the Romans were coming north—after all, hadn’t the steppe Danes beaten back the furious Mongols, the Rus, the Poles, and anyone else that had dared enter their domain?

However, Bataczes didn’t oblige to an immediate battle. On the morning of July 27th, 1262, after his scouts made contact with the larger Danish force, Bataczes backpedaled slowly, stopping and turning about three times. Each time, the Danes also halted and began to put themselves in battle array, when the Romans suddenly broke ranks and began to move yet again.

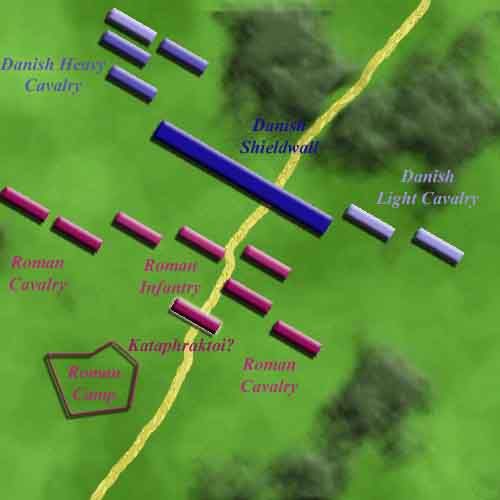

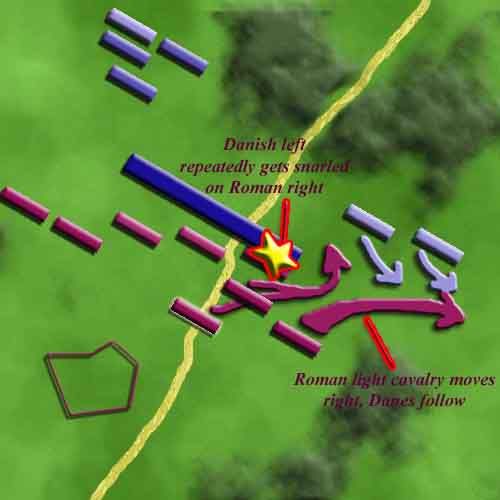

Finally near 3 PM and just outside his own camp, Bataczes’ men turned to finally fight. The Roman command had selected his ground carefully—the Danes were forced to deploy with woods at their back, while the Roman right was partially covered by woods. Despite these tactical obstacles, the tired and thoroughly annoyed Danes deployed for battle opposite their Roman counterparts.

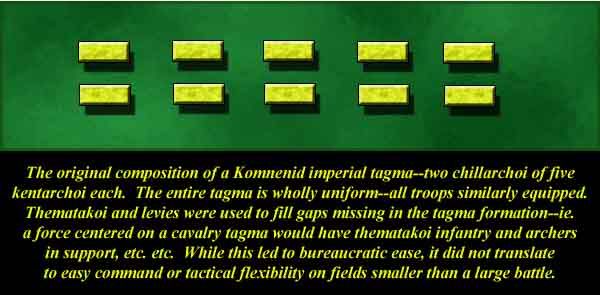

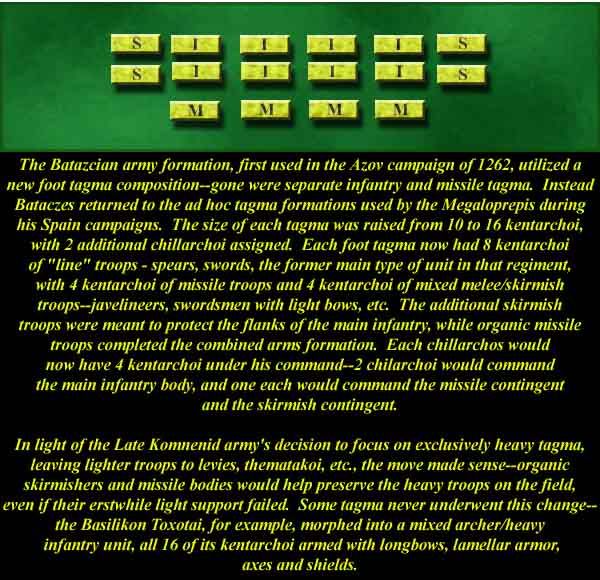

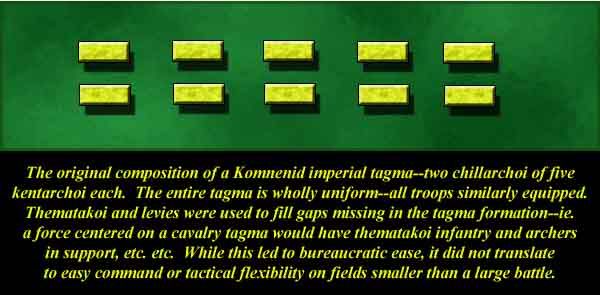

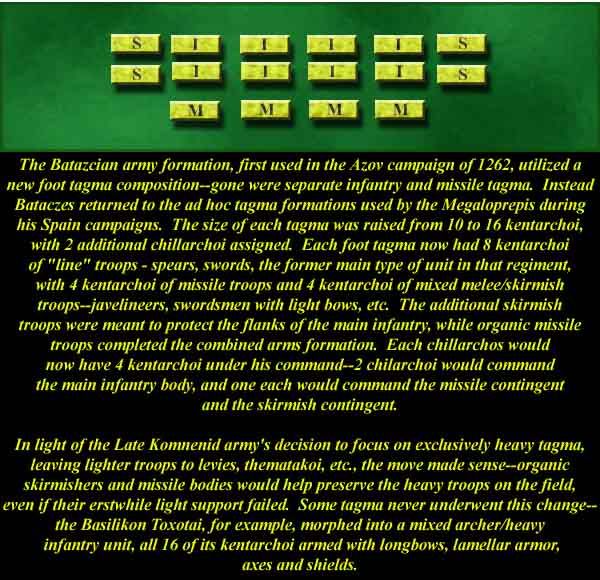

The Roman deployed his much smaller army in an unusual formation—the three foot tagmata at its core were arrayed en echelon from southwest to northeast. The central infantry tagmata were ad hoc formations, fundamentally different from the old imperial tagma. The fields of Azov were where Bataczes hoped to test his ideas on army composition—he probably did not imagine these standardized forces would become the new focus of the Late Komnenid Army.

Behind these forces, Bataczes seemingly arrayed his army in the standard Roman fashion—the lighter cavalry tagmata and thematakoi of the steppe were deployed to the wings, while the gleam of kataphraktoi mail glinted from the rear of the Roman spearline. Significantly, Bataczes’ echelon allowed for the cavalry on his right to deploy closer to the Danish line, while his left was partially refused, making that flank harder to attack.

Opposite the Romans, King Olaf arrayed his much larger Sortmarker army—even with the detachments left to continue the Azov siege, the force numbered 25,000 foot and nearly 15,000 horse. The Danish leiðangr shieldwall, made of yeomen and foot retainers from the cities of the steppe, occupied the center of the Danish line. These men were hardy and tough—while less heavily armored than their Roman counterparts and less disciplined, they were certainly capable of holding the line against a determined enemy.

Behind these, the Danish King then aligned the true core of Sortmark’s army—her feared cavalry. The King placed his personal Húskarlar cavalry in the rear, to the right of the Danish line—the place of honor, and where Olaf intended to launch his primary attacks on the Roman army. Other jarls and their lendmenn also crowded on the Danish right—Jarl Thorkil Estridsson, Jarl Knud Hvide, and countless others amongst the great and mighty of the Danish realm. The Sortmarker Hestrleiðangr, those commoners who had adopted the steppe-style of mounted combat, formed the cavalry on the Danish left.

Olaf’s strategy was simple—his force was larger, and he intended to pin the Roman center in place with his infantry while the heavy Sortmark battles broke the Roman left through repeated charges. The húskarlar and lendmenn were well equipped for the task—they were equipped with heavy mail (and in the case of the King’s personal húskarlar, barding for their horses as well), lances, and bone-crushing axes. While by royal decree all of them carried a bow and two quivers of arrows, those were weapons of last resort, against enemies who refused to stand their ground and fight—Mongols, Pechenegs, or Cumans.

Olaf’s Hestrleiðangr held no such scruples—indeed, the Hestrleiðangr had been the secret to the surprise success of Sortmark over the last century. Yet despite their important military position, these common folk and yeomen were not according positions of honor—bows were acceptable weapons for these lesser folk. Their role in Olaf’s plan was to pin down the Roman right flank through harassing fire, while victory and glory went to the King and his heavily armed retainers on the opposite side of the battlefield.

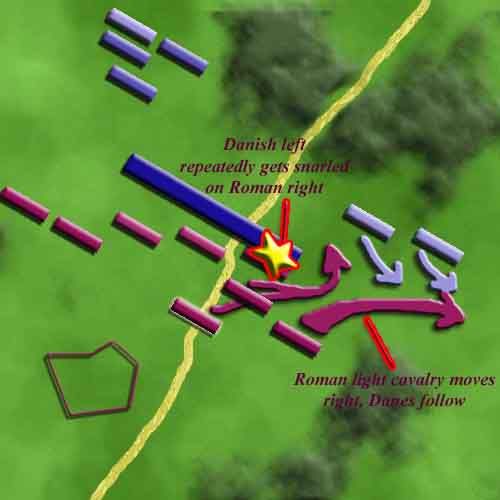

The engagement began with the Sortmarker infantry pressing forward, but the Roman oblique deployment disrupted the leiðangr shieldwall, creating gaps for the Roman lighter skirmish units to infiltrate and cause havoc on the Danish left. The shieldwall pulled back before it became fully engaged, regrouped, and tried yet again. Three successive attacks were mounted, and while the Romans gave ground, they didn’t break, nor were they fully held in place. The Danish King and his heavy cavalry were thus compelled to sit on their right flank, waiting for the moment when the Romans were unable to move so they could successfully attack the distant, refused Roman flank.

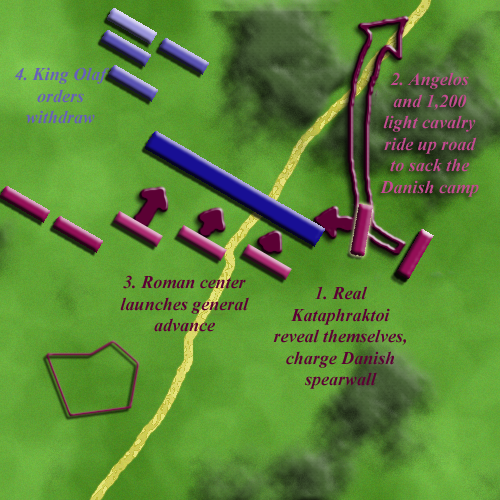

Meanwhile, as the Danish left reformed for yet another attack, the Romans were on the move—Bataczes himself led a force forward straight at the flank of the shieldwall, even as a tagma of light cavalry rode to the far Roman right, pulling much of the Danish Hestrleiðangr after. The Danes undoubtedly saw these shabbily dressed riders moving forward at a slow trot with long spears and were confused. No light cavalry would have moved so slowly, so deliberately towards the shieldwall, bristling as it was with leiðangr archers, and no light cavalry would have tried to charge on formed men with lances. Yet onward the host came, two deep, abnormally long spears at the ready, their banners furled. The Danish thegns on the left ordered their archers to open up. Against lightly armored Cuman riders, the archer fire would be devastating…

…but the unfortunate leiðangr on the Danish left did not face lightly armored men of the Skythikon tagma.

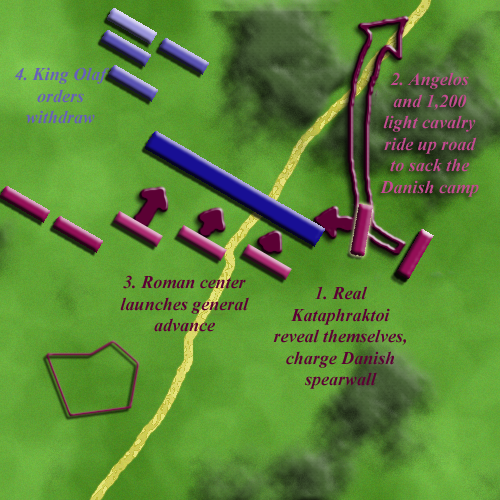

The ‘Cumans’ shrugged off the fire from the Danish light bows—and it was probably then that the leiðangr realized what they faced wasn’t another ride of light cavalry intent on harassing their already tiring formation. If they hadn’t, once that long line reached two hundred yards from the Sortmark line, all doubt disappeared. A horn sounded, we are told, long and low, followed by another, then another, and rider after rider yanked off their mottled furs—and the brilliant sheen of metal glinted bright in the afternoon light. Banners unfurled, trumpet calls echoed, as the Athanatakoi tagma of kataphraktoi revealed itself in all its glory.

Bataczes the night before had ordered extra furs confiscated from the Cherson docks to be sewn loosely onto the armor of the Athanatakoi tagma, making the men, from the distance, appear to not be heavily armored kataphratkoi. Bataczes even ordered the horse with barding on the front of the line and several horses in from the flanks to have furs sewn onto their barding as well—the extra weight, as well as heat, meant the kataphratkoi had to advance at a walk till the absolute last second before breaking into a charge. A few excess helms and breastplates for the actual Kumanatoi completed the trick.

Their disguises gone, another horn sounded, and Bataczes shouted the

words that had long since entered into Roman legend—“κατάφρακτοι, έτοιμος κοντοι!”

“Kataphraktoi, ready kontos!”

We can only imagine the terror in the leiðangr as 1,200 kataphraktoi lowered their lances, and with Bataczes himself at their lead, or how the ground shuddered and the world turned to turmoil as those long lances cracked the flank of the Danish line.

Yet Bataczes’ whirlwind did not stop there.

The Roman Strategos knew his heavy cavalry was good for one charge, and one charge only. So behind them, hidden behind their wide mass came his Kumanatoi tagma of light cavalry, charging in and through the gaps made by the kataphraktoi and into the rear of the Danish army. Their orders were simple—one chillarchoi was ordered to roll up the Danish flank as best it could. The other, led by none other than 18 year old Ioannis Angelos of later infamy, would charge directly for the Danish camp, its supplies, and the secondary mounts and seasonal foals that kept the Danish cavalry ahorse.

To his credit, King Olaf read the writing on the wall, and decided on seeing his left flank crack that discretion was the better part of valor, ordering his army to retire from the field—the Danish army was larger, in its own element, it could afford a setback and come back to fight again. In fact, Danish right and center retired in good order, but the Danish left routed from the field, the leiðangr fleeing back to their hearths and homes. However, an organized retreat takes time—time the Danes did not have.

For if the legends are to be believed, young Ioannis Angelos first earned his reputation in that pell-mell charge past the cataphracts into the rear of the Danish army, rampaging through the Danish camp, setting it ablaze and taking over a thousand prisoners of war, as well as most of the Danish camp followers and the all important backup mounts. Once there, enraged at an injury caused by an angry Danish camp follower that would eventually cost him his eye, Angelos took a page from the book of the Bulgarontocus—he blinded all his male prisoners, save every tenth one, then, after stripping them of clothes and arms, sent two kentarchoi to herd them towards the retreating Danish army. The sight was so horrible that Olaf’s columns ground to a halt. Within minutes of that terrible sight, order amongst the leiðangr broke down—instead of an organized but retreating force, the Danish King soon had a panicked mob surrounding him and the lendemenn and huskarlar.

Angelos dispatched another kentarchoi to drive the Danish secondary mounts out of the camp, while he personally led his final unit in the most gruesome (and, like the blindings, unauthorized) act of the day—he and those 300 men set about beheading as many of the camp followers as possible, then throwing the detritus into bags. As Olaf’s army milled about in confusion and the rest of Bataczes army rumbled forward towards the Danish rear, according to legend Angelos crudely labeled each bag with writing in both Greek and Danish:

“Kneel or die.”

The arrival of fifty horses, laden down with sacks, was said to have made the Danish King faint.

While we cannot confirm if the legend is true, what we do know is that, pinned between his ruined camp and a shambling mass of blinded men and the spear-line of the Roman army, King Olaf lost his nerve. A rider galloped towards the man Roman army, bearing a flag of truce.

Future historians have called the terms offered by Bataczes generous—Olaf and his army were allowed to retire to Sortmark, the King was to pay the Roman Empire a yearly tribute of 1,000 pounds of silver and 100 pounds of gold for the next ten years, and his three sons, Karl, Skjalm, and Svein, were to be sent to Konstantinopolis for their “education.” However, one must keep in mind the absolute disaster Angelos running the Danish secondary mounts into the steppe was for the Sortmarker army. Without their secondary mounts, the Sortmarker cavalry, especially the hestrleiðangr, were hamstrung. Just as importantly, the loss of the mounts meant the Sortmarker ability to breed replacement mounts was similarly hamstrung for the foreseeable future. In fact, between 1264 and 1268 the King of Sortmark was forced to send embassies to the Rus and even as far afield as Samarkand and France seeking horses…

So Romanion manages to push back one enemy, but another is already preparing to mass on the border. How many Persians are coming? A lot will depend on the decisions of a distant man somewhere between Delhi and Samarkand—Arghun Khan could mean the difference between a small army of bandits and brigands moving into Anatolia, versus an organized Persian offensive 19 tagmata strong. Meanwhile, Ioannis Angelos has made a name for himself (if bloodily), while Bataczes has earned a laudable victory… will this general be as loyal as everyone assumes he is? And what’s coming in Spain? More plots in Konstantinopolis as Rome AARisen continues!

"Κάλλιο να σου βγει το μάτι παρά το όνομα."

"It's better to lose an eye than to get a bad name." – Roman proverb.

June 7th, 1262

Alexandros Komnenos, Junior Emperor of Persia, glowered at the instrument in his right hand. His face wrinkled up, and for a moment, its dark scowl made him look older than his 30 years. The silver instrument in his hand blandly glinted back, as if mocking its master. It’d been a gift from his wife Šahrzād—that alone would have made him glower.

She’d even commented he’d needed it to learn, “proper manners.”

That was three weeks ago, the last time he’d seen her and son and namesake Alexandros—the boy was five, and surprisingly quiet like his uncle Nikephoros. Alexandros could only barely tolerate that Persian trollop, but he loved his ‘Little Alex’ more than his own life. Being kept from seeing him because of Thomas’ ‘insistence’ that preparations had to be made for his madcap army made Autokrator Alexandros Komnenos an angry man.

An angry man whose furious gaze was directed at the cause of this missing time—his cousin, the self-styled Thomas IV, Emperor of the Romans.

Alexandros was sure his dimwitted cousin had no idea how fortunate he was that the junior Persian Emperor’s mouth was currently filled with mutton. For in Alexandros’ hand was a wondrous invention used by the locals called a fork, and its doubly pointed prongs could just as easily find their way into Thomas’ eye as they could the mutton sitting on the Emperor’s plate.

“…and abd-al Nasif also raised 4,500 men from Gilan,” Thomas droned on, detailing the contribution of this ‘noble’ or that ‘elect man.’ Almost all were Muslim, and more than a few were no elites of any regard—the ones Alexandros recognized he knew to be tribal leaders from the mountains of Gilan or Azeribjian, not the leaders of any organized, civilized people. The junior emperor swallowed, and promptly stuffed another piece of mutton into his mouth, before looking over at his elder brother.

Nikephoros Komnenos only folded his arms and gave one of his perpetual sighs.

“That’s 25,000 men,” the senior Persian Emperor nodded. Nikephoros at 32 still looked beefy, hale and hearty, even if he still spoke quietly. Unlike Alexandros, who sat and ate his lunch in silks befitting an emperor, Nikephoros looked, and felt, much more at home in his half-kit armor. Also unlike his younger brother, the elder Emperor was not sitting—he leaned against one of the doorways to the small room.

“125,000, you mean,” Thomas interrupted. “Surely that Spain has erupted, and the Danes are on the move, you’re going to support my claim with your armies?”

Alexandros scowled—Thomas had opened his mouth at a moment when Alexandros’ mouth was not filled with food. Before he could catch his tongue, the junior of Gabriel’s sons spoke.

“No,” he said, stopping angry words from tumbling out. His cousin was daft!

“And why not?” Thomas demanded, hands on his hips like he was wont to do. Alexandros shoved another bit of mutton in his mouth, but at his cousin’s imperious stare, he decided to speak anyway—rude or no.

“Arghun Khan has defeated Altani Khatun,” Alexandros muttered once his mouth was cleared of mutton. “Thrice, actually. Took Samarkand and spared the city once she knelt as his vassal.”

“And what does that have to do with my claim to my rightful throne?” Thomas asked dangerously. “Altani Khatun was your father’s enemy, and he bested her! Besides,” Thomas waved his hand dismissively, “she’s in Samarkand! What does that have to do with Romanion?”

“Nothing,” Nikephoros grunted, “and everything.”

“Nothing and… what do you mean?” Thomas frowned, clearly perplexed. Alexandros sighed—his cousin could have always been considered a dullard at best.

“We can’t fully back you without leaving Persia exposed,” Nikephoros explained gently, while Alexandros snorted, stabbing the mutton with his ‘fork’ once more and biting another chunk. The device really was ingenious, he had to admit.

“And if ‘dis Arghun, or Mahmu’th, as he’s now calling hi’thself,” Alexandros waved the fork around as he spoke, “has taken Samarkan’th, he’th now on our bor’ther.” He swallowed. “And if he’s bested Altani, its only a matter of time before he starts looking our way. We aren’t going to leave Persia exposed.”

Alexandros watched as his cousin’s face fell. The stupid boy. He looked over at his brother—Nikephoros shook his head gently. Alexandros stabbed his fork into another piece of mutton and stuffed his face. It kept his mouth shut.

“But,” Nikephoros jumped in before Thomas could lodge a complaint, “we are willing to send three tagmata, plus levies…”

“Three tagmata? Out of thirteen?” Thomas hissed.

“25,000 soldiers,” Nikephoros nodded. “They’ll have barracks in Samarra and Mosul…”

“So they won’t even follow my crusaders across the border?” their cousin complained. “Even if you send those troops, that’d bring my men to 50,000! Imagine what we could do if we went into Anatolia with 50,000! That little brat has his armies in Cherson and Spain! He…”

“…has seven tagmata in his Anatolian army that are untouched!” Alexandros finally snapped. Was Thomas blind, or a fool? Hadn’t he seen the reports? The grain provision numbers that their contacts spoke of? Yes, many of the young whelp’s soldiers went West and North. And those ten didn’t even count the eight in the Reserve Army Asbjorn’s people spoke about! “Do you want us to lurch into a war with an enemy at our back, against superior numbers?!”

“You’ll have my men!” Thomas angrily spat back, on his feet.

“Useless lot they are!” Alexandros was up too, his face inches from his cousins’s. “Tribesmen! Louts! The dregs of mankind! How will those boys with wicker shields and shaky spears stand against mailed skoutatoi!? Idiot!” Alexandros added harshly. As his cousin’s face went ashen and broken, he spat onwards. “Do you think we’re fools that’ll lunge into this with only a codpiece on?”

“What about Georgios Donauri’s?” Thomas shouted onwards.

Alexandros cleared his throat—he felt a thick wad of spit on his tongue, and it took all his will to spit at the ground, not at his cousin. “He’s the only man the Church hates more than my father!”

“At least father is still a Christian,” Nikephoros added glumly. “Not a follower of Aionymos or Aionyos…” Alexandros didn’t see his brother’s confused shrug, but he knew it was there. Saying Georgios II Donauri of Arabia had converted to the words of some madman from the desert wasn’t the truth—Georgios took the sacraments and confessed his sins as any good Christian, but the Patriarch of Jerusalem was incensed that the son of the famous strategos of the same name not only let the hajj continue unfettered, but let men like the one calling himself “Timeless One” preach in the streets of Jeddah and Mecca. Already, Alexandros had heard from merchants in Karbala and Najaf that every year, more and more people came to Mecca not for the hajj but to hear the words of this Aionios, as he called himself in Greek. While Alexandros might join the Patriarchs in disapproving of how lenient Georgios had become, he couldn’t fault the man—he and his court were lone Christians in a heathen sea, far more so than even the court in Persia.. Some leniency meant survival, more could be a godsend, as Georgios’ popularity with the people in his Kingdom testified.

“But he said…”

“…an empty promise!” Alexandros cut his cousin off. “He promised you what? 10,000 men?”

“20,000!” Thomas’ jaw jutted forward. Alexandros thought he looked like some proud crane, strutting about moments before a hunter’s arrow struck it down.

“Arabia doesn’t even have 10,000 men, Thomas,” Nikephoros sighed. “Georgios sent you some empty words, so that in the…” Nikephoros stopped suddenly. Alexandros couldn’t help but smile darkly. Nikky always had the more careful tongue, something Alexandros found himself thankful for on more than one occasion.

“…once you won,” Nikephoros said in a deadpan, “he could get you to pressure the Patriarch of Konstantinopolis to call off his Jerusalem hounds.”

For several seconds, Thomas stood, mouth agape, like some twisted oak halfway between standing tall and lurching over to the ground. Finally, a single word escaped his obviously confused lips.

“Oh.”

“Alexandros is right, Thomas,” Nikephoros advanced into the verbal gap, not letting either cousin take advantage of the silence, “you have many eager men, but they aren’t trained, and they aren’t well equipped. Hold your troops just inside the border, outside of Baghdad,” Nikephoros sighed. “Train them, and we can see about equipment,” the eldest brother added, pinching the bridge of his nose. Alexandros frowned—that was a sign his brother was in thought, and the thought he was mulling was something Alexandros might not like…

“You mean…” Alexandros started to interrupt, but Nikephoros simply talked over him.

“Thomas is right too, Alexandros,” the eldest, and thus senior, said quietly. “Now is perhaps the best time we’ll have in decades to do something about Konstantinopolis. Thomas’ men are raw, but given some discipline, even the rawest recruits can gain a spine.” He pinched his nose again. “It will take time… Alexandros, you’re the better captain of the barracks, you should look to his recruits, while I see to their equipment.”

Alexandros started to open his mouth to complain, but he bit off his words before they leaked out. Nikephoros was up to something—he always was up to something. Usually it was clever, and usually it was to Alexandros’ benefit—so the younger brother folded his arms and listened.

“Probably a year?” Nikephoros raised an eyebrow.

“At least,” Alexandros finally huffed. “Most wouldn’t know a kontos if I swung it and hit them in the head. A year might turn them into acceptable light troops. Holding a battleline against skoutatoi?” He pursed his lips and shook his head.

Nikephoros nodded. “Good. A year will give me time to make preparations in the East—calling up some politkoi to watch the frontiers, perhaps shift a few of them and a tagma or two West...” Nikephoros grunted, “…and gauge what is going on with the Mongols. If they look threatening, we can hold some troops back. If they look distracted…” A thin smile finally crossed his normally dour lips.

“However,” the eldest Komnenid present added, looking squarely at Thomas. “Our help will have a price.”

“Name it,” Thomas folded his arms, grinning at Alexandros in triumph.

“My brother and I are co-Emperors to you, equal in rank and authority, of all of Romanion and her dominions,” Nikephoros said simply.

“But, it’s my…”

“Our,” Alexandros glanced momentarily at his brother, before stepping closer to his cousin, “throne, dear cousin. Our throne. Just as our fathers were joint rulers, so shall we be.”

“But…”

“No joint imperial title, no army,” Alexandros crossed his arms. He didn’t need to look at his brother to know he was nodding as well. Nikephoros always came up with the plans—Alexandros wasn’t happy, but he hoped this turned out like his brother’s other schemes…

==========*==========

Battle of Azov

From Sandra Levy-Day’s Fire and Reform: The Last Komnenid Army, University of Cordoba Press, 1984:

…The Battle of Azov is certainly not remarkable in Roman history for its size—while very large for the standards of its day, the Romans fielded much larger armies elsewhere during the campaigns of 1262-1265. If anything, the one remarkable thing about the Azov campaign was the sheer aggressiveness of Bataczes. Roman tradition on the steppe had called for cautious, even reserved campaigns—every Roman commander facing a foe on the Russian steppe had first lured them away from the steppe—Emperor Manuel towards the Black Sea coast, the Megaloprepis into the Kodori Valley. After his landing in Cherson, however, Isaakios Bataczes did exactly the opposite—after five days of raiding the theme’s stores for weapons and supplies, the Roman commander sailed across the Straits of Kerch to Tmutarakan, then began a frantic march north.

While many have commented that Bataczes did this with inferior numbers as well (some 25,000 versus 50,000 Danes sieging Azov and laying waste to the entire theme), this historian is inclined to remind them that the Roman army was a disciplined, almost wholly tagmata host, compared to the Danish force which had many levies as well as a hardened, veteran core. Thus, the number disparity is deceiving.

A new theory put forward by J.D. Hanson is that Bataczes’ speed came at a price—his army marched with few food stores beyond a limited pack train. This would explain why Bataczes was able to march so quickly, covering 60 miles in three days—and also would explain why the Roman was so eager to do battle, before his men had to fight on empty stomachs, or worse, his force would have to divide to forage.

On hearing the news of Bataczes’ landing, King Olaf did not remain idle—the Sortmarker lord left 10,000 men to mind the siege lines, while the bulk of his army, still a handsome 40,000, moved rapidly south to intercept. The Sortmarkers were enthusiastic that the Romans were coming north—after all, hadn’t the steppe Danes beaten back the furious Mongols, the Rus, the Poles, and anyone else that had dared enter their domain?

However, Bataczes didn’t oblige to an immediate battle. On the morning of July 27th, 1262, after his scouts made contact with the larger Danish force, Bataczes backpedaled slowly, stopping and turning about three times. Each time, the Danes also halted and began to put themselves in battle array, when the Romans suddenly broke ranks and began to move yet again.

Finally near 3 PM and just outside his own camp, Bataczes’ men turned to finally fight. The Roman command had selected his ground carefully—the Danes were forced to deploy with woods at their back, while the Roman right was partially covered by woods. Despite these tactical obstacles, the tired and thoroughly annoyed Danes deployed for battle opposite their Roman counterparts.

The Roman deployed his much smaller army in an unusual formation—the three foot tagmata at its core were arrayed en echelon from southwest to northeast. The central infantry tagmata were ad hoc formations, fundamentally different from the old imperial tagma. The fields of Azov were where Bataczes hoped to test his ideas on army composition—he probably did not imagine these standardized forces would become the new focus of the Late Komnenid Army.

Behind these forces, Bataczes seemingly arrayed his army in the standard Roman fashion—the lighter cavalry tagmata and thematakoi of the steppe were deployed to the wings, while the gleam of kataphraktoi mail glinted from the rear of the Roman spearline. Significantly, Bataczes’ echelon allowed for the cavalry on his right to deploy closer to the Danish line, while his left was partially refused, making that flank harder to attack.

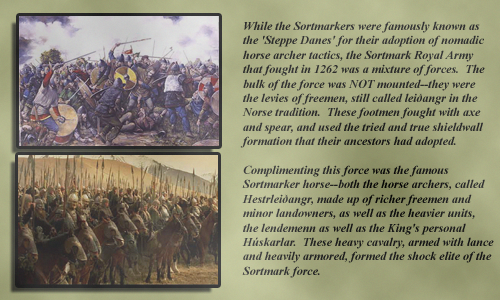

Opposite the Romans, King Olaf arrayed his much larger Sortmarker army—even with the detachments left to continue the Azov siege, the force numbered 25,000 foot and nearly 15,000 horse. The Danish leiðangr shieldwall, made of yeomen and foot retainers from the cities of the steppe, occupied the center of the Danish line. These men were hardy and tough—while less heavily armored than their Roman counterparts and less disciplined, they were certainly capable of holding the line against a determined enemy.

Behind these, the Danish King then aligned the true core of Sortmark’s army—her feared cavalry. The King placed his personal Húskarlar cavalry in the rear, to the right of the Danish line—the place of honor, and where Olaf intended to launch his primary attacks on the Roman army. Other jarls and their lendmenn also crowded on the Danish right—Jarl Thorkil Estridsson, Jarl Knud Hvide, and countless others amongst the great and mighty of the Danish realm. The Sortmarker Hestrleiðangr, those commoners who had adopted the steppe-style of mounted combat, formed the cavalry on the Danish left.

Olaf’s strategy was simple—his force was larger, and he intended to pin the Roman center in place with his infantry while the heavy Sortmark battles broke the Roman left through repeated charges. The húskarlar and lendmenn were well equipped for the task—they were equipped with heavy mail (and in the case of the King’s personal húskarlar, barding for their horses as well), lances, and bone-crushing axes. While by royal decree all of them carried a bow and two quivers of arrows, those were weapons of last resort, against enemies who refused to stand their ground and fight—Mongols, Pechenegs, or Cumans.

Olaf’s Hestrleiðangr held no such scruples—indeed, the Hestrleiðangr had been the secret to the surprise success of Sortmark over the last century. Yet despite their important military position, these common folk and yeomen were not according positions of honor—bows were acceptable weapons for these lesser folk. Their role in Olaf’s plan was to pin down the Roman right flank through harassing fire, while victory and glory went to the King and his heavily armed retainers on the opposite side of the battlefield.

The engagement began with the Sortmarker infantry pressing forward, but the Roman oblique deployment disrupted the leiðangr shieldwall, creating gaps for the Roman lighter skirmish units to infiltrate and cause havoc on the Danish left. The shieldwall pulled back before it became fully engaged, regrouped, and tried yet again. Three successive attacks were mounted, and while the Romans gave ground, they didn’t break, nor were they fully held in place. The Danish King and his heavy cavalry were thus compelled to sit on their right flank, waiting for the moment when the Romans were unable to move so they could successfully attack the distant, refused Roman flank.

Meanwhile, as the Danish left reformed for yet another attack, the Romans were on the move—Bataczes himself led a force forward straight at the flank of the shieldwall, even as a tagma of light cavalry rode to the far Roman right, pulling much of the Danish Hestrleiðangr after. The Danes undoubtedly saw these shabbily dressed riders moving forward at a slow trot with long spears and were confused. No light cavalry would have moved so slowly, so deliberately towards the shieldwall, bristling as it was with leiðangr archers, and no light cavalry would have tried to charge on formed men with lances. Yet onward the host came, two deep, abnormally long spears at the ready, their banners furled. The Danish thegns on the left ordered their archers to open up. Against lightly armored Cuman riders, the archer fire would be devastating…

…but the unfortunate leiðangr on the Danish left did not face lightly armored men of the Skythikon tagma.

The ‘Cumans’ shrugged off the fire from the Danish light bows—and it was probably then that the leiðangr realized what they faced wasn’t another ride of light cavalry intent on harassing their already tiring formation. If they hadn’t, once that long line reached two hundred yards from the Sortmark line, all doubt disappeared. A horn sounded, we are told, long and low, followed by another, then another, and rider after rider yanked off their mottled furs—and the brilliant sheen of metal glinted bright in the afternoon light. Banners unfurled, trumpet calls echoed, as the Athanatakoi tagma of kataphraktoi revealed itself in all its glory.

Bataczes the night before had ordered extra furs confiscated from the Cherson docks to be sewn loosely onto the armor of the Athanatakoi tagma, making the men, from the distance, appear to not be heavily armored kataphratkoi. Bataczes even ordered the horse with barding on the front of the line and several horses in from the flanks to have furs sewn onto their barding as well—the extra weight, as well as heat, meant the kataphratkoi had to advance at a walk till the absolute last second before breaking into a charge. A few excess helms and breastplates for the actual Kumanatoi completed the trick.

Their disguises gone, another horn sounded, and Bataczes shouted the

words that had long since entered into Roman legend—“κατάφρακτοι, έτοιμος κοντοι!”

“Kataphraktoi, ready kontos!”

We can only imagine the terror in the leiðangr as 1,200 kataphraktoi lowered their lances, and with Bataczes himself at their lead, or how the ground shuddered and the world turned to turmoil as those long lances cracked the flank of the Danish line.

Yet Bataczes’ whirlwind did not stop there.

The Roman Strategos knew his heavy cavalry was good for one charge, and one charge only. So behind them, hidden behind their wide mass came his Kumanatoi tagma of light cavalry, charging in and through the gaps made by the kataphraktoi and into the rear of the Danish army. Their orders were simple—one chillarchoi was ordered to roll up the Danish flank as best it could. The other, led by none other than 18 year old Ioannis Angelos of later infamy, would charge directly for the Danish camp, its supplies, and the secondary mounts and seasonal foals that kept the Danish cavalry ahorse.

To his credit, King Olaf read the writing on the wall, and decided on seeing his left flank crack that discretion was the better part of valor, ordering his army to retire from the field—the Danish army was larger, in its own element, it could afford a setback and come back to fight again. In fact, Danish right and center retired in good order, but the Danish left routed from the field, the leiðangr fleeing back to their hearths and homes. However, an organized retreat takes time—time the Danes did not have.

For if the legends are to be believed, young Ioannis Angelos first earned his reputation in that pell-mell charge past the cataphracts into the rear of the Danish army, rampaging through the Danish camp, setting it ablaze and taking over a thousand prisoners of war, as well as most of the Danish camp followers and the all important backup mounts. Once there, enraged at an injury caused by an angry Danish camp follower that would eventually cost him his eye, Angelos took a page from the book of the Bulgarontocus—he blinded all his male prisoners, save every tenth one, then, after stripping them of clothes and arms, sent two kentarchoi to herd them towards the retreating Danish army. The sight was so horrible that Olaf’s columns ground to a halt. Within minutes of that terrible sight, order amongst the leiðangr broke down—instead of an organized but retreating force, the Danish King soon had a panicked mob surrounding him and the lendemenn and huskarlar.

Angelos dispatched another kentarchoi to drive the Danish secondary mounts out of the camp, while he personally led his final unit in the most gruesome (and, like the blindings, unauthorized) act of the day—he and those 300 men set about beheading as many of the camp followers as possible, then throwing the detritus into bags. As Olaf’s army milled about in confusion and the rest of Bataczes army rumbled forward towards the Danish rear, according to legend Angelos crudely labeled each bag with writing in both Greek and Danish:

“Kneel or die.”

The arrival of fifty horses, laden down with sacks, was said to have made the Danish King faint.

While we cannot confirm if the legend is true, what we do know is that, pinned between his ruined camp and a shambling mass of blinded men and the spear-line of the Roman army, King Olaf lost his nerve. A rider galloped towards the man Roman army, bearing a flag of truce.

Future historians have called the terms offered by Bataczes generous—Olaf and his army were allowed to retire to Sortmark, the King was to pay the Roman Empire a yearly tribute of 1,000 pounds of silver and 100 pounds of gold for the next ten years, and his three sons, Karl, Skjalm, and Svein, were to be sent to Konstantinopolis for their “education.” However, one must keep in mind the absolute disaster Angelos running the Danish secondary mounts into the steppe was for the Sortmarker army. Without their secondary mounts, the Sortmarker cavalry, especially the hestrleiðangr, were hamstrung. Just as importantly, the loss of the mounts meant the Sortmarker ability to breed replacement mounts was similarly hamstrung for the foreseeable future. In fact, between 1264 and 1268 the King of Sortmark was forced to send embassies to the Rus and even as far afield as Samarkand and France seeking horses…

==========*==========

So Romanion manages to push back one enemy, but another is already preparing to mass on the border. How many Persians are coming? A lot will depend on the decisions of a distant man somewhere between Delhi and Samarkand—Arghun Khan could mean the difference between a small army of bandits and brigands moving into Anatolia, versus an organized Persian offensive 19 tagmata strong. Meanwhile, Ioannis Angelos has made a name for himself (if bloodily), while Bataczes has earned a laudable victory… will this general be as loyal as everyone assumes he is? And what’s coming in Spain? More plots in Konstantinopolis as Rome AARisen continues!

Okayyy  ferocious little bastard, blinding and beheading prisoners of war! I forsee a brilliant but short career for the little Ioannis, most people with those kind of tendencies tend to accumulate a lot of enemies. Nice update, as per usual, BT. I really liked the overview of the "Batazeian reform", I just have one question though; kentarchoi is a "grecification" of the latin centuria, and I know chillarchos means "ruler of a thousand", so how many men does a kentarchoi consists of?

ferocious little bastard, blinding and beheading prisoners of war! I forsee a brilliant but short career for the little Ioannis, most people with those kind of tendencies tend to accumulate a lot of enemies. Nice update, as per usual, BT. I really liked the overview of the "Batazeian reform", I just have one question though; kentarchoi is a "grecification" of the latin centuria, and I know chillarchos means "ruler of a thousand", so how many men does a kentarchoi consists of?

And just a little nit picking; Alexandros really shouldn't be unfamiliar with forks, seeing as forks were first introduced to Venice by a Roman (Byznatine) princess around 1000ad.

And just a little nit picking; Alexandros really shouldn't be unfamiliar with forks, seeing as forks were first introduced to Venice by a Roman (Byznatine) princess around 1000ad.

Poor Danes.

If I were Alexandros (Whom I start to like. Lavish, brilliant strategist that cares not about what others think? Hell yeah!) I would stroke Thomas down and be done with it. Do they really need him as a bloody claimant? They've got claims triple as good, Thomas' army could be easily convinced they are better employers, so why?!

And Nooooooooooooo! at the mongols in Japan. The Land of the Rising Sun should be kept clear of foreign influence!

EDIT : After Flying Dutchies post I realised something. A possibility of the Emperor taking control of Japan 700 years early!

If I were Alexandros (Whom I start to like. Lavish, brilliant strategist that cares not about what others think? Hell yeah!) I would stroke Thomas down and be done with it. Do they really need him as a bloody claimant? They've got claims triple as good, Thomas' army could be easily convinced they are better employers, so why?!

And Nooooooooooooo! at the mongols in Japan. The Land of the Rising Sun should be kept clear of foreign influence!

EDIT : After Flying Dutchies post I realised something. A possibility of the Emperor taking control of Japan 700 years early!

Last edited:

So I guess I was right with Angelos having the Imperial March as tune? Yay, whats mt prize  .

.

Also, Mongols actually claiming part of Japanese soil? One can only guess at the effects it could have on the future. No kamikaze-myth, foreign influences forced upon them and now a history of fighting united against foreign invaders are a huge change to Japanese history. Will the shoguns become even more xenophobe after expelling the Mongols, or more open to foreign influences?

Also, Mongols actually claiming part of Japanese soil? One can only guess at the effects it could have on the future. No kamikaze-myth, foreign influences forced upon them and now a history of fighting united against foreign invaders are a huge change to Japanese history. Will the shoguns become even more xenophobe after expelling the Mongols, or more open to foreign influences?

Took 40 delicious minutes to read that.

The best way to annihilate steppe people is to kill their horses.

Maybe we get a new horse race, 'Wild Scythian'-horses.

I don't get the purpose of Chagatai khanate. In the middle, sitting there, doing nothing...

The best way to annihilate steppe people is to kill their horses.

Maybe we get a new horse race, 'Wild Scythian'-horses.

I don't get the purpose of Chagatai khanate. In the middle, sitting there, doing nothing...

The LAST Komnenid army?? Aren't most armies in the Mediterranean area Komnenid at this point? This is going to be quite a collapse! I can't wait!

The Kamakura Shogunate wasn't particularly xenophobic in the first place, they just had no interest in export and they never imported anything except monks, so there wasn't a huge amount of trade with the mainland. But then, there hadn't been since the middle Heian period.

I actually doubt that a Mongol victory would result in a big increase in foreign influence, particularly if the Mongols are already characterizing themselves as Shoguns - technically an Imperial court rank, which might suggest they're now acting in the name of a puppet emperor. The Mongols were fairly hands-off rulers, after they'd won and finished massacring the current rulers, anyway, so the interesting thing would be to see how the internal politics are rearranged in the wake of a Mongol conquest/defeat. The possibilities I can see are as follows.

Native Japanese victory scenarios:

1a. Kamakura Pyrrhic victory: the Kamakura Shogunate pushes the Mongols off the island, but at the cost of their tight control over their vassals, who start accumulating local, then national power until they topple the Shogunate and erect a less centralized Shogunate in its place.

2a. Kamakura kickin'-it-like-it's-1185 victory: the Kamakura turtle up in the north and build war bureaucracy and coalitions, letting their enemies exhaust themselves and weaken the power of the lesser lords, then lead their coalition of toughened eastern warriors to drive the decadent westerners into the sea. It worked against the Heike, but would it would it work against the Mongols?

3a. Kamakura partial victory: the Kamakura exhaust themselves, but also the Mongols, leading to a split Japan, possibly along the lines of the Northern and Southern courts OTL. Given the Mongols' limited ability to project their power over long distances in the long run, I would expect the Kamakura to win the waiting game, then get devoured from within by ambitious lords who've suddenly acquired large(r) private armies and the label "daimyo". So, basically the Sengoku jidai, but 200 years early and without the intervening Muromachi Shogunate.

Mongol victory scenarios:

1b. Meet the new Shogun, just like the old Shogun: the fact that the Mongols are calling themselves Shoguns (technically an Imperially bestowed title) suggests that they're buying into the existing Ritsuryo system (rather, the fiction of a Ritsuryo system that helped cover up the un-Imperial workings of the actual government), at least nominally. They'd probably have an Imperial country cousin they've set up as pretender, or perhaps they have the actual emperor and the Kamakura have the pretender. In any case, the Mongol Shoguns would probably set up a government not too dissimilar from the Kamakura Shogunate, and would intermarry and be completely Japanized within a few generations.

2b. Off with their heads!: Or, they could raze everything to the ground and import enough Mongol nobles and Chinese/Korean bureaucrats to start a new, truly foreign government. Then we'd really be in unknown waters, although I think it likely that like in Russia, the native culture would slowly reassert itself in the next century and a half, and we'd have a centralized Japanese military dictatorship again by the 15th century. The real question would be what this would mean for the imperials, and the evolution of Shintoism.

3b. Mission accomplished: Mongol exhaustion could drive them to the negotiating table. With an expensive war in China, the Mongols might accept nominal submission and/or cash from the Kamakura, then use that as an excuse to declare victory and leave. The financial drain and loss of prestige would probably leave the Kamakura open to internal threats, though, so I don't think the Mongols would collect many payments.

As for the Kamikaze myth, I expect any regime that needed proof of divine favor would be able to find another suitable myth if it looked hard enough, and with any outcome other than 2b they could even claim Japan had never been conquered ("The Mongols didn't conquer anyone! They were invited in by the legitimate Emperor Totally-not-a-Pretender to support him against the Kamakura in his rightful, divine struggle to blah blah etc."). What I really want to know is which side has the Imperial regalia, and how the Mongol invasion will affect the claim of unbroken Imperial reign.

Hm...

General, can we have a "State of Japan" update sometime? Pretty please? 桜をかけてお願いいたします?*

*I entreat thee, with cherries on top [of my head].

So I guess I was right with Angelos having the Imperial March as tune? Yay, whats mt prize.

Also, Mongols actually claiming part of Japanese soil? One can only guess at the effects it could have on the future. No kamikaze-myth, foreign influences forced upon them and now a history of fighting united against foreign invaders are a huge change to Japanese history. Will the shoguns become even more xenophobe after expelling the Mongols, or more open to foreign influences?

The Kamakura Shogunate wasn't particularly xenophobic in the first place, they just had no interest in export and they never imported anything except monks, so there wasn't a huge amount of trade with the mainland. But then, there hadn't been since the middle Heian period.

I actually doubt that a Mongol victory would result in a big increase in foreign influence, particularly if the Mongols are already characterizing themselves as Shoguns - technically an Imperial court rank, which might suggest they're now acting in the name of a puppet emperor. The Mongols were fairly hands-off rulers, after they'd won and finished massacring the current rulers, anyway, so the interesting thing would be to see how the internal politics are rearranged in the wake of a Mongol conquest/defeat. The possibilities I can see are as follows.

Native Japanese victory scenarios:

1a. Kamakura Pyrrhic victory: the Kamakura Shogunate pushes the Mongols off the island, but at the cost of their tight control over their vassals, who start accumulating local, then national power until they topple the Shogunate and erect a less centralized Shogunate in its place.

2a. Kamakura kickin'-it-like-it's-1185 victory: the Kamakura turtle up in the north and build war bureaucracy and coalitions, letting their enemies exhaust themselves and weaken the power of the lesser lords, then lead their coalition of toughened eastern warriors to drive the decadent westerners into the sea. It worked against the Heike, but would it would it work against the Mongols?

3a. Kamakura partial victory: the Kamakura exhaust themselves, but also the Mongols, leading to a split Japan, possibly along the lines of the Northern and Southern courts OTL. Given the Mongols' limited ability to project their power over long distances in the long run, I would expect the Kamakura to win the waiting game, then get devoured from within by ambitious lords who've suddenly acquired large(r) private armies and the label "daimyo". So, basically the Sengoku jidai, but 200 years early and without the intervening Muromachi Shogunate.

Mongol victory scenarios:

1b. Meet the new Shogun, just like the old Shogun: the fact that the Mongols are calling themselves Shoguns (technically an Imperially bestowed title) suggests that they're buying into the existing Ritsuryo system (rather, the fiction of a Ritsuryo system that helped cover up the un-Imperial workings of the actual government), at least nominally. They'd probably have an Imperial country cousin they've set up as pretender, or perhaps they have the actual emperor and the Kamakura have the pretender. In any case, the Mongol Shoguns would probably set up a government not too dissimilar from the Kamakura Shogunate, and would intermarry and be completely Japanized within a few generations.

2b. Off with their heads!: Or, they could raze everything to the ground and import enough Mongol nobles and Chinese/Korean bureaucrats to start a new, truly foreign government. Then we'd really be in unknown waters, although I think it likely that like in Russia, the native culture would slowly reassert itself in the next century and a half, and we'd have a centralized Japanese military dictatorship again by the 15th century. The real question would be what this would mean for the imperials, and the evolution of Shintoism.

3b. Mission accomplished: Mongol exhaustion could drive them to the negotiating table. With an expensive war in China, the Mongols might accept nominal submission and/or cash from the Kamakura, then use that as an excuse to declare victory and leave. The financial drain and loss of prestige would probably leave the Kamakura open to internal threats, though, so I don't think the Mongols would collect many payments.

As for the Kamikaze myth, I expect any regime that needed proof of divine favor would be able to find another suitable myth if it looked hard enough, and with any outcome other than 2b they could even claim Japan had never been conquered ("The Mongols didn't conquer anyone! They were invited in by the legitimate Emperor Totally-not-a-Pretender to support him against the Kamakura in his rightful, divine struggle to blah blah etc."). What I really want to know is which side has the Imperial regalia, and how the Mongol invasion will affect the claim of unbroken Imperial reign.

Hm...

General, can we have a "State of Japan" update sometime? Pretty please? 桜をかけてお願いいたします?*

*I entreat thee, with cherries on top [of my head].

Last edited:

So, I guess the guy on the right is Angelos? I'm still not sure about the other guy though.

Nice update. I'd also like to second the motion for a "State of Japan" it looks like an interesting situation.

Now all we need is for good ol' Isaac Batatzes to turn around and take Constantinople. Then we can see a real Byzantine dynasty in action.

Then we can see a real Byzantine dynasty in action.

A bad one that is?

I very much want to know how Arghun defeated Altani and to what degree he's consolidated that conquest. If they have some sort of amicable working relationship, that's very bad news for Persia indeed. But if he decides to launch new campaigns in India or turn and drive on Kashgar in the East instead...

Last edited:

So much to say!

---------------

1) Alanti defeated? So much for a christian mongol state...

2) Man, I don't know why but reading this post made me feel that Alexandros is a little fatty (but it could be that i am hungry... )

)

3) Why is Sergo's head still not on a plate!?!

4) Where is my native Persian dynasty

5) Very nice update, nice and long and very satisfying battle overview

6) Oh, and if (or maybe when) you would like to make an interim I believe it would be very cool to discuss how Roman/Byzantine society, culture, and technology have changed over the last couple of centuries

Until the next update I will be lurking...

---------------

1) Alanti defeated? So much for a christian mongol state...

2) Man, I don't know why but reading this post made me feel that Alexandros is a little fatty (but it could be that i am hungry...

3) Why is Sergo's head still not on a plate!?!

4) Where is my native Persian dynasty

5) Very nice update, nice and long and very satisfying battle overview

6) Oh, and if (or maybe when) you would like to make an interim I believe it would be very cool to discuss how Roman/Byzantine society, culture, and technology have changed over the last couple of centuries

Until the next update I will be lurking...

The Japanese will beat the mongols back, it's inevitable. The mongols just aren't suited to fighting in Japan in general, and they'd be unable to match the Japanese at their own game, considering warfare in Japan really wasn't changed so much as perfected in the last five centuries or so, the Japanese have just a LITTLE more practice. Local support for the mongols would be almost non-existant, they're an island, (No land connection to the rulers always seems to foster rebelliousness.) they've got a rather different culture, to say the least, (Horse nomads turned into faux-Chinese Imperials are decidedly dissimilar to our Japanese friends at this time.) and they have already ground to a halt, losing the momentum, and they have more than just this distraction to deal with. Also, by this time I am sure the Mongols have become notorious even in Japan for their cruelty upon seizing cities, meaning they could either A- Capitulate Immediately (Not bloody likely, they'd all have to stab themselves in the guts afterwards anyway.) or B- Resist until the bloody end, and then stab themselves in the guts before capture. (Sounds a bit more Japanese.) The Mongols simply don't have the resources to fight the Japanese in a straight up Total War, having to ship men overseas, on enemy soil, mostly disadvantageous terrain, with an enemy who has perfected the art of fighting on the very same terrain. The Mongols have been stalled in the West in Russia and Persia, and India is seemingly another quagmire of endless sieges against the Hindi states still resisting, and I'm sure the jungles of Southeast Asia will prove as forbidding to the Mongols as in our history. If the Japanese stop the Mongols, which seems likely, the Mongols will have truly reached the limit of their conquests. Even if they DO take Japan, that's about as far as they're going anyways, (Mongols in America? Blasphemy!) so we're approaching the absolute height of the Mongol Empire before it begins it's decline, perhaps beginning to decline nearly at the same time as the Byzantine Empire finally reaches it's peak as well. I wonder which of these truly colossal powers will gasp it's last metaphorical breath first, and if the other will be strong enough to profit from their misfortune.

Last edited:

Gods, what an update!

And I'm mainly speaking of the maps. I love those maps. I need to also start making maps of my own.

And thus, comments:

1. I LOVE Nikephoros and Alex. I've never seen brothers rule together more effectively, ever. Which is a great change from the backstabbity usual.

2. Arabia - why make concessions to it if it is useless militarily?

3. Altani defeated! NOOOOOOO! I hope her children pull a Mughal on the Delhi Mongols. The Mongols, by the way - revival of Buddhism in India, or are they more dependent on the Muslims for administration? How's the Tibet ties?

More importantly, both the Delhi and Yuan need horses. Who sells them the horses?

4. Japan - Japan is fairly flat around the areas where most (like, the vast chunk) of the population is concentrated, so control is not as difficult as it may seem. Also, the Koreans working for the Yuan may be really entrenching themselves all over Japan in place of the Sea Clans, being better sailors in general. In fact, Japan may be the lumber mill that supplies Korean shipyards.

So two things could bring down the Mongol Shogunate: Korean betrayal and a desire to finally solve the supremacy of Yuan vs. Japanese Emperors. That last one is a serious question.

5. Sortmark!

I'm liking the whole break with lances, exploit with Cumans. Sensible way of fighting. Same with the organic pezhetaroi.

Batatzes is onto something. I predict that after the plagues come rolling through Europe (and the Empire with its wretched urban millions), that is how all the armies will look. And plagues are unavoidable.

And I'm mainly speaking of the maps. I love those maps. I need to also start making maps of my own.

And thus, comments:

1. I LOVE Nikephoros and Alex. I've never seen brothers rule together more effectively, ever. Which is a great change from the backstabbity usual.

2. Arabia - why make concessions to it if it is useless militarily?

3. Altani defeated! NOOOOOOO! I hope her children pull a Mughal on the Delhi Mongols. The Mongols, by the way - revival of Buddhism in India, or are they more dependent on the Muslims for administration? How's the Tibet ties?

More importantly, both the Delhi and Yuan need horses. Who sells them the horses?

4. Japan - Japan is fairly flat around the areas where most (like, the vast chunk) of the population is concentrated, so control is not as difficult as it may seem. Also, the Koreans working for the Yuan may be really entrenching themselves all over Japan in place of the Sea Clans, being better sailors in general. In fact, Japan may be the lumber mill that supplies Korean shipyards.

So two things could bring down the Mongol Shogunate: Korean betrayal and a desire to finally solve the supremacy of Yuan vs. Japanese Emperors. That last one is a serious question.

5. Sortmark!

I'm liking the whole break with lances, exploit with Cumans. Sensible way of fighting. Same with the organic pezhetaroi.

Batatzes is onto something. I predict that after the plagues come rolling through Europe (and the Empire with its wretched urban millions), that is how all the armies will look. And plagues are unavoidable.