I. Regency

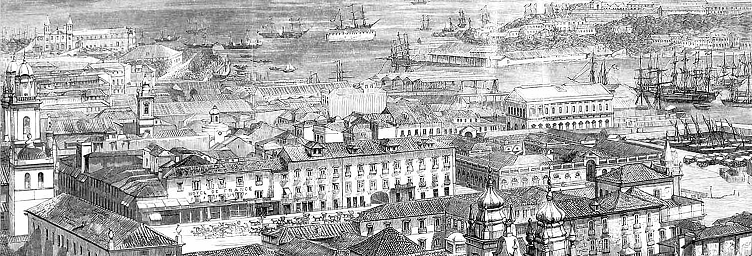

Rio de Janeiro, Capital of the Empire circa 1835

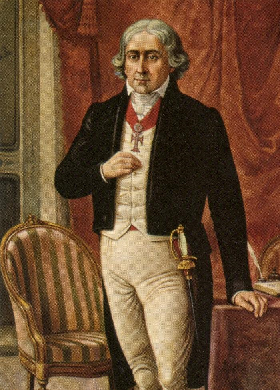

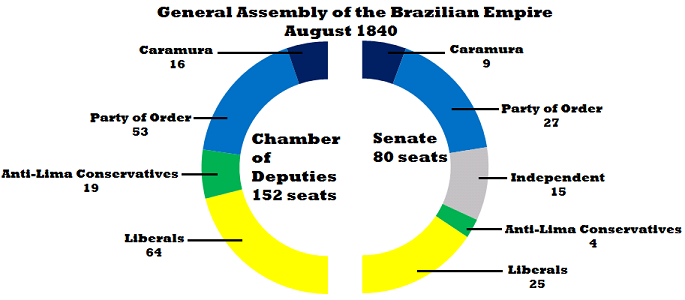

On 23rd July 1840, in Rio de Janeiro, something incredible happened. The political cliques of the young Brazilian Empire, the liberals and conservatives, courtiers and slavers, monarchist and republicans, came together to renounce their power. For nine years since the founder of their nation Dom Pedro I had left to defend his daughter’s throne across the ocean, a regency had overseen the rule of his successor Pedro II, a five year old boy. Despite the best efforts of the child’s father the semi-absolutist constitution of the Empire relied on a unifying figure to function. The first regent, appointed by Pedro I prior to his abdication in 1831, was Jose Bonifacio de Andrada. A scholar and advisor during the tumultuous War of Independence, Andrada was highly respected in Rio, but he was no politician. Unlike the Emperor the position of Regent was answerable to the General Assembly, split between the elected Chamber of Deputies and noble Senate. It wasn’t long before the vested interests of the nation manoeuvred to depose Andrada. Spuriously accused of treason by the Assembly in 1833, Andrada was sent into exile to be replaced by Diogo Antonio Feijo.

Feijo was a lay priest and leader of the Nativist faction, a collection of liberal Deputies united solely through their opposition to what they saw as the authoritarian power of the monarchy. Containing a strong republican faction, the Nativists and Feijo quickly set about attempting to alter the constitution to reduce Imperial power and more importantly entrench themselves as the leading force in Brazilian politics. In the former they found allies in the Coimbra Bloc

[1], consisting of aristocratic and landowner interests who sort to decentralise power to this respective regions. Led by Pedro de Araujo Lima, the Coimbra Bloc controlled the Senate and together with the Nativist Deputies created a tentative coalition known as the Moderate Party, giving them a majority in both Houses. Opposed to the Moderates was the third force in the Assembly, collectively known as the Caramura

[2]. A group of reactionary intellectuals, nobles and military officers, they sort the restoration of Pedro I and the establishment of an autocratic government. United by ideology rather than self-interest the Caramura, despite making up no more than ten percent of the Assembly, were a formidable and cohesive faction.

Regent Jose Andrada and his usurper, Diogo Feijo

The low voting threshold for the Chamber of Deputies quickly saw the Nativists and the populist Feijo come to dominate the Assembly and by extension the Regency

[3]. In 1834 the Moderate alliance passed the Additional Act, which altered the constitution, federalising the Empire to popular acclaim. The effects of the Act however proved disastrous for commoners. With political power in the provinces greatly increased, the local cliques effectively created one-party states, shutting out opponents from government, administration and commerce. The Assembly lacked the power to directly intervene and many simply had no reason to. Members of the Coimbra Bloc profited greatly from the new local situation while Feijo was interested solely in controlling the capital and the young Emperor’s court. This dereliction of duty led to an explosion of violence, corruption and even outright revolt in the provinces. In Maranhao and Grao-Para in the north, ranchers, peasants and slaves united in uprisings against white landowners throughout the 1830s leading to sporadic, unenthusiastic Army expeditions to put them down. A similar revolt also broke out amongst the gauchos of Rio Grande do Sul on the border with Uruguay. Government lethargy to these

Farrapos [4] would prove a grave mistake.

By 1835 the pact between Feijo and Lima was wearing thin. With the passing of the Additional Act the Coimbra Bloc had little to gain from the coalition while Feijo’s increasingly dictatorial stance hardly endeared them to the Regent. As early as 1833 the Nativists had attempted what amounted to a constitutional coup, putting a motion through the Assembly to abolish the Senate and the Council of State, the cabinet of the Regent and only direct check on his powers. A joint effort by the Coimbra Bloc and Caramura had halted the effort with the help of veiled threats of military intervention but Feijo’s power base meant he suffered only a temporary loss of control. Since then the Regent had moved slowly, expelling or bribing Council members who opposed to him, until he held absolute control over the executive. In April 1835 Feijo managed to squeak through an election to continue as Regent. This would prove the apex of his reign. In September 1834 news had reached Rio de Janeiro of Pedro I’s death, removing the central restorantionist tenet of the Caramura. Rather than dissolve, the reactionary party turned their ire directly on Feijo and his liberal, republican leanings.

Leaders of the Coimbra Bloc: Pedro Lima and Carneiro Leao

Lima's protege, Carneiro Leao, soon approached the Caramura leadership with suggestions of a conservative alliance. The re-election of Feijo cast away any misgivings the reactionaries might have had and the Regent’s grip on the Assembly began to dissolve. Feijo’s decline was greatly helped along by the Rio Grande revolt. Initially just another social uprising in a poor region of the Empire, by 1836 it had escalated into a full blown secessionist revolution. Feeling ignored by the capital and isolated from the slaver-planter elite that dominated the Empire, the Farrapos led by Bento Goncalves

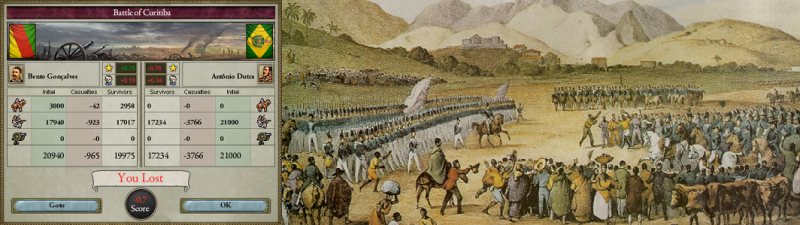

[5] had declared independence for the Riograndese Republic. Supported with arms and funds from the Rosas regime in Argentina it wasn’t long before the entire province had fallen to the rebels. As usual Feijo reacted slowly, sending regiments piecemeal, expecting the gauchos to flee before Imperial troops. Goncalves, a professional soldier and Independence War veteran, had raised a formidable army 20,000 strong and smashed each government force in turn. By April, surprised by the timid response, the rebels marched north along the coast intent on capturing Rio de Janeiro to force Brazilian recognition of the Republic.

It was only now after the string of government defeats that Feijo, under intense pressure from all factions including his own, called a general mobilisation to crush the revolution and save the capital. A hastily gathered army led by General Antonio Dutra marched south to confront Goncalves, meeting him near Curitiba on 3rd May. Though matched in numbers, the ill-prepared Brazilian conscripts proved no match for the battle-hardened rebels. A people used to hunting and riding, the Farrapo riflemen proved their marksmanship while gaucho cavalry tore through the government lines. Dutra retreated to Rio de Janeiro, prompting mass panic as civilians fled in anticipation of the invading army. The defeat doomed Feijo. Though he could not be legally removed as Regent until the Assembly voted in 1838, the Deputies and Senators rounded on him. The Nativists, hardly a coherent party beforehand defected in droves to Lima’s coalition. His base now gone, Feijo accepted Coimbra and Caramura members into the Council of State, making Lima de facto ruler of the Empire. He quickly organised reinforcements to be ferried from the north, consisting of veterans of the Grao-Para uprisings. Crucially at this moment Goncalves halted to rest the men and await his own reinforcements.

1st Battle of Caritiba, 3rd May 1836 | Government Forces muster near Rio de Janeiro

As such General Dutra met the rebels once more outside Curitiba on 18th June, this time with experienced troops and an almost 2-to-1 numerical advantage. The rebels were beaten, losing thousands of irreplaceable soldiers in the process. Dutra pressed the advantage, harrying Goncalves towards Porto Alegre, the Riograndese capital. Over the coming months the two commanders had several battles through the province. Every time the Brazilians suffered the lion’s share of casualties yet forced the Farrapos from the field, driving inexorably into rebel territory. While government forces only increased, the all-volunteer Riograndese army disintegrated as thousands of soldiers lost hope in the cause and returned home. The last major confrontation of the war, the Battle of Santa Maria near the Argentine border, saw the rebels smashed. Hungry, tired and dejected, the Farrapos fought for several hours before Goncalves surrendered to Dutra. As acting president of the Republic, Goncalves issued a decree across the region for his men to stand down. Many did not listen however and it would not be until November 1837 that the last organised rebels under Antonio Neto agreed to government amnesty. A large garrison would nonetheless remain in the region for almost a decade to ensure no future revolts.

Battle of Santa Maria, 12th December 1836 | Last Stand of the Farrapos

Back in Rio de Janeiro the new government breathed a sigh of relief. With small-scale revolts still on-going across Brazil and the Coimbra Bloc not interested in reversing the decentralisation of power wholesale, they passed an amendment to the Additional Act granting the central government power over provincial law enforcement, in order to intervene directly in future unrest. After the violence of recent years, the measure angered many as a poor compromise. Former Nativists led by the Viscount of Caravelas quickly broke with Lima over the issue. Even moderate Coimbra Deputies like Zacarias Vasconcelos made their displeasure known but with Feijo’s clique gone, there was simply no organised opposition to Lima’s new conservative alliance. No organised opposition in the Assembly at least. By April 1838 and Lima’s official election as Regent, a group known as the Courtier’s Faction had made themselves known. Made up of advisors and high-ranking servants to Pedro II in the Imperial Palace, they had first coalesced as supporters of Andrada. Under the autocratic Feijo they had little input but with Lima dependent on the support of the ultra-royalist Caramura, they began to make headway.

Led by Aureliano Coutinho they quickly became a nuisance, using their influence in the Senate to block Lima’s appointments to the Council of State. The Courtiers looked to the displaced liberals as allies of convenience as well. Having shed the legacy of Feijo, Senators like Dom Caravelas and Deputies like Francisco de Paula were desperate to regain influence. Egged on by Coutinho they began lobbying for the end of the Regency, for the Emperor to be declared of age. With Pedro only twelve years-old at the time it was a clear effort to depose Lima and replace him with Pedro as a puppet. Despite this many within the Caramura were supportive. Supporters of Andrada as well, a ‘purist’ minority led by the first regent's brother, Antonio Carlos, sided with the opposition. By 1839, Lima’s coalition was starting to break apart. Ironically he had quickly come to enjoy the power of the Regency and with his loyalists began acting in much the same manner as Feijo, ejecting critics from the Council of State and using their majority in the Senate to ignore the growing opposition.

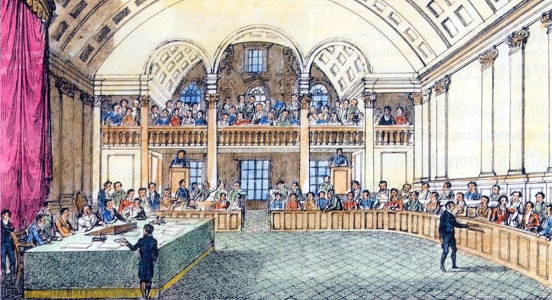

The Chamber of Deputies: Centre of the mounting anti-Lima coalition in 1839

Lima’s rump was based heavily around the coffee plantation owners of the south and this period was a massive boom time for coffee exports as duties were slashed and rivals muscled out of the market. This favouritism angered many. Due to the corrupt nature of the boom the state collected little revenue and in order to balance the budget Lima proposed new taxes. Such a move required a vote in the Assembly and it was now his disparate opponents united. Rebel Coimbra member Zacarias Vasconcelos was the figurehead, splitting the Bloc as he demanded a compromise in exchange for the legislation. The opposition wanted the Regent-appointed Council of State abolished and replaced with a cabinet drawn directly from the Assembly. Hoping to avoid a total loss of power, Lima accepted and much to his annoyance Vasconcelos was chosen as chief of the cabinet, making him de facto prime minister. For obvious reasons the two struggled to work together. Lima was used to complete control, while Vasconcelos did his level best to break up the Regency cabal. Finally in December Lima could take no more and removed Vasconcelos.

The dismissal caused outrage in the Assembly as the opposition denounced Lima as a tyrant and the entire cabinet resigned. Lima struggled for months attempting to cobble together a new government but beyond opportunists and non-entities he found few supporters. Deciding to avoid a putsch like his predecessor suffered, Lima proposed a constitutional amendment that would see Pedro II brought into government slowly until his official coronation in 1842 when the Regent would stand down. It was too little too late. With an early majority now favoured by all the opposition wanted Lima gone and gone quick. The opposition, a ragged band of republicans, liberals, absolutists and rebel conservatives, also had no interest in seeing one faction gain total dominance. Many, having seen the chaos and back-stabbing of the Regency simply wanted it to be at an end. It was decided unanimously by a vote in the Assembly on 23rd July 1840 that Pedro II would be given his majority effective immediately. And that is how a legislature of cutthroat politicians gave executive control of the largest nation in the Western Hemisphere to a fourteen year old boy.

Coronation of His Imperial Majesty Dom Pedro II [6]

[1] So-called because all of its leaders had graduated from Coimbra University.

[2] Named after Diogo Alvares Correia, a 16th century Portuguese explorer known to the Tupi natives as Caramuru. He is seen as something of a founding father of colonial Brazil.

[3] Brazil had a franchise based on wealth but was low enough that practically everyone bar Indians, slaves and tenant farmers (plus women of course) could vote. Post-Reform Act Britain’s electorate for instance was a fifth that of contemporary Brazil by percentage.

[4] Disdainful term for ranchers and gauchos that translates literally as ‘tatters’ referring to their weathered clothes but is commonly translated to ragamuffin.

[5] Though a staunch monarchist Goncalves was that fed up with Feijo he gave in to radical pleas and became the one and only president of Rio Grande.

[6] Despite looking pretty 'mature' for a fourteen year old, this is the real painting of the coronation, guessing its just artistic license.