A Kingdom In the Clouds: A Ü-Tsang AAR

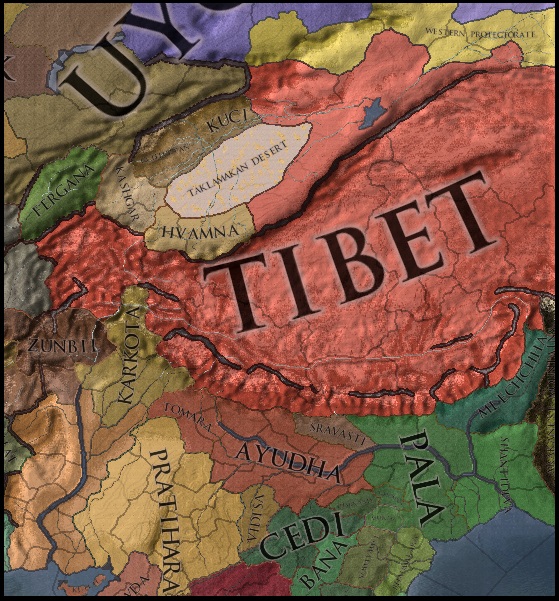

The Tibetan Empire in 769 AD.

'They grow no rice but have black oats, red pulse, barley, and buckwheat. The principal domestic animals are the yak, pig, dog, sheep, and horse. There are flying squirrels, resembling in shape those of our own country, but as large as cats, the fur of which is used for clothes. They have abundance of gold, silver, copper, and tin. The natives generally follow their flocks to pasture and have no fixed dwelling-place. They have, however, some walled cities. The capital of the state is called the city of Lohsieh. The houses are all flat-roofed and often reach to the height of several tens of feet. The men of rank live in large felt tents, which are called fulu. The rooms in which they live are filthily dirty, and they never comb their hair nor wash. They join their hands to hold wine, and make plates of felt, and knead dough into cups, which they fill with broth and cream and eat the whole together.'

- The Old Book of the Tang

'The men and horses all wear chain mail armor. Its workmanship is extremely fine. It envelops them completely, leaving openings only for the two eyes. Thus, strong bows and sharp swords cannot injure them. When they do battle, they must dismount and array themselves in ranks. When one dies, another takes his place. To the end, they are not willing to retreat. Their lances are longer and thinner than those in China. Their archery is weak but their armor is strong. The men always use swords; when they are not at war they still go about carrying swords.'

— Du You, the Tongdian

Tibet in 867 AD.

Rulers of Ü-Tsang

- Gyalpo Purgyal Yumtän I (867 to 877 AD)

- Gyalpo Purgyal Palkhorre 'the Brute' (877 to 920 AD)

- Gyalpo Purgyal Yumtän II 'the Festive' (920 to 947 AD)

- Queen Mother Zhang Que (947 to 961 AD)*

- Gyalpo Purgyal Yumtän III (961 to 985 AD)

- Gyelmo Purgyal Torma I (985 to 987 AD)

- Regency Council (987 to 1003 AD)

- Gyalpo Purgyal Dharmapala 'the Glorious' (1003 to 1032 AD)

- Lama Namzhungsten (1032 to 1041 AD)*

- Gyalpo Purgyal Sumnang (1041 to 1063 AD)

- Gyelmo Purgyal Torma II 'the Philosopher' (1063 to 1110 AD)

- Gyalpo Purgyal Daktri 'the Merry' (1110 to 1114 AD)

- Gyelmo Purgyal Pelmo 'the Scholar' (1114 to 1158 AD)

- Gyalpo Purgyal Selbar I 'the Merry' (1158 to 1179 AD)

- Gyalpo Purgyal Selbar II 'the Cruel' (1179 to 1186 AD)

- Tsenpo Purgyal Selbar 'the Cruel' (1186 to 1198 AD)

* As regent.

Last edited:

.jpg)