Act I Chapter Thirty-Seven

THIRTY-SEVEN.

The Defeat

21 June 1592 – 1 July 1596

I.

21 June 1592 – 3 June 1594

The Defeat

21 June 1592 – 1 July 1596

I.

21 June 1592 – 3 June 1594

‘Have you been keeping cool this summer?’

‘I go swimming.’

‘I see.’

There was an awkward pause. Otakar and Vasilisa sat a little apart, uncomfortably so. Otakar had to come out and say it outright—there was no way around it.

‘Lisa… about what happened in the Great Hall.’

‘You’re not going to tell Mama and Otec about it, are you?’ asked Vasilisa, her voice taut with anxiety.

‘No,’ said Otakar simply. ‘I want to talk to you about it, though. Lisa, I’m over thrice your age. I’m not going to say it’s wrong for you to be interested in boys, but… someone younger, surely…!’

‘You won’t always be thrice my age. And I don’t want just “someone younger”,’ Lisa pulled a morose face. ‘I want you.’

Otakar made a noise of frustration. ‘Lisa—you’re my best friend’s daughter. I was a guest in your house when your mother was pregnant with you! I’ve known you since you were a baby!’

‘Yeah,’ Vasilisa said, ‘you’re my dad’s best friend. I’ve known you forever. That’s how I know you’ll love me. You won’t toy with me or hurt me or look down on me.’

‘That’s it, Lisa,’ Otakar turned to face her fully. ‘That’s exactly it. I don’t look down on you. I don’t want to toy with you and I certainly don’t want to hurt you! But—that’s just the reason I can’t give you what you want from me. It wouldn’t be fair to you. You’re still a child, and I’m an old man. A broken, foolish, stubborn old man. You deserve far better than me.’

‘Nice speech,’ Vasilisa pulled a wry face. ‘But it won’t change how I feel about you.’

Otakar held his head in his hands. Vasilisa was nothing if not sincere: that was the problem. However sincere a thirteen-year-old girl might be in a profession of love, her knowledge wasn’t equal to the depth of her feeling. She had no inkling of how tangled the relations between man and woman could be. Whatever she knew about him came at her through the stylised, idealised, abstracted lenses of youth. She might know him, but she didn’t truly know him.

What made it worse was that there was a small, perverse corner of Otakar’s mind that did want her to know him that way. Otakar saw the best of his best friend in her, and indeed the best of his best friend’s wife. She had Artemie’s honesty. She also had his protectiveness—anyone who saw her together with Pavol could see that. And she had Nadeža’s big, sweet, wide-open heart, brimming with compassion. Once or twice Otakar had fancied that when she grew older, she might be just the sort of woman he could love. But not yet!

‘Then, please,’ Otakar told her, ‘do us both a favour. Wait a few years. I’m not saying no to you, I’m just saying—wait. Wait until more of my faults become apparent to you, and then see if you feel the same.’

Vasilisa reached out to hold his hands—only to hold, not to drag to where they didn’t belong—and earnestly held his gaze. ‘I will wait… wait until the Dread Judgement, and my heart shall be as it is now.’

~~~

‘Vaše Veličenstvo,’ said the fashionably-ruffed delegate from Bratislava, ‘I am as grieved as I’m sure you are to hear of the defections of merchants from my town to Wien, and from Praha to Sachsen. But I beg your consideration. The duties and tolls that you exact upon goods from other kingdoms place our own merchants in an intolerable bind when they try to sell elsewhere. Might you not consider lightening that burden somewhat?’

Tomáš considered, and was about to make a reply, when the doors to the Great Hall burst open, and a rather bedraggled, black-avised figure strode in, ignoring the stir of mutters around him from the court, and taking a place beside the Bratislava worthy. The distinction between the two was striking, but Tomáš motioned for the man to take his place to be addressed next.

‘The policy we have enacted,’ said the king to the Bratislava merchant, ‘is ultimately one that is best not only for Moravia’s nobility and farmers, but also for her moneyers and domestic artisans. I can understand that some of the merchants who do cheap abroad might be slightly put out by it, but as king I am answerable for the common weal, not merely that of one section of the burghers. This is all the reply that I can give.’

The Bratislava merchant bowed and withdrew—none too gladly, but obediently. And the dark-haired, olive-skinned man who had just arrived there took his place before the throne.

‘May God preserve your Highness forever,’ said the man. ‘I am Metrofane Ferrari of Verona, in what was once the Kaloēthēan Despotate. As most of the people in that city are, I am a brother of yours in the True Faith. The Bishop of Rome, however, is insistent upon the return of the Italian cities of the north to his personal sway and to his schismatic notions. I beg and implore you upon your humanity and upon our brotherhood—come swiftly to our aid, for we are surrounded upon all sides by enemies!’

In contrast to the Bratislava merchant, there was only one reply that Kráľ Tomáš could make to this. He was honour-bound, and honour was at the core of his being. There was also the fact that the Kaloēthēs imperial family in Constantinople had once again elected to make themselves rivals to their northern coreligionists, and for Tomáš to have refused this call for aid would have meant ceding the field to Eastern Rome in terms of religious legitimacy.

The armies of Moravia were called up. At fifty-one years, his blond hair streaked with white, Captain Artemie Štefánik was getting close to retirement age, but he still took his dutiful place in the First Army at the head of Spiš’s Second Regiment of charge infantry. But by now two new faces were shown at the Army’s head, at the behest of Preškapitán Oleg Karásek ze Lvovic: Barón Totil von Schwarzenberg, and Hrabě Mojmír z Otradovic. Each of them was granted a generalship and a leadership position at the head of one of Moravia’s armies. But…

‘I hope that it is well understood,’ said the Bavarian Ambassador Nikolaus Hermann Wenzel Maria Anton von Ernst to Kráľ Tomáš before his troops moved out, ‘that although Bayern wishes you speed and victory in this contest against the earthly power of the Bishop of Rome, and grants safe harbour and passage with all goodwill to Moravia’s troops, I fear that mein Fürst can make no promise of any aid in arms. I am somewhat loath to put it so bluntly, but: we have our own Alpine border to mind.’

‘Of course,’ said Tomáš. ‘This isn’t your fight and I had no intention of making it so.’

A number of Italian mercenary companies, however, did offer their services to the Moravian Crown—whether out of religious feeling, or out of more pecuniary concerns. However, Tomáš made no effort to engage their services. The First and Second Armies marched southward through Bayern toward Verona.

The Moravians reached the borders of the Papal State far too late to come to Verona’s aid—particularly not against an army fifty three thousand strong. They thus settled for taking and occupying the Papal city of Trento. However, a confrontation between the two powers could not be long delayed.

‘It is better to fight them here,’ advised Captain Artemie, ‘than on a battlefield of Castinus’s choosing. Let us move at once on Verona. If we can take them by surprise, before they are fully mustered, we might stand a chance.’

‘I appreciate your input, sir,’ replied Barón Totil von Schwarzenberg politely to the veteran, ‘and it shall be taken under advisement.’

Artemie’s advice was not taken, however. Totil delayed. And that delay cost Moravia bitterly.

The armies of Pope Castinus 2. moved—not to liberate Trento, but instead on a northeasterly path through the Alps. Barón Totil, taken aback by this move, decamped from Trento and force-marched his armies to intercept the Papal armies before they reached the Moravian border. Totil backtracked and marched to Mariazell in Austria, where he set up his armies to hold the Seeberg Pass in Steiermark.

The Papal forces attacked. Although Totil held bravely, a series of reinforcements to the Pope’s troops came from the West, from an unexpected quarter: the smaller kingdom of Rheinfranken, which was allied with the Pope in his crusade against the Orthodox Italian cities. At the head of these reinforcements was a French-Swiss general of noble extraction named Frédéric de Avesnes-Hohenschwangau.

Avesnes-Hohenschwangau fielded a dominating amount of artillery power, which he brought to bear against the Moravian rear. The Franconian advance caught the Moravians by surprise, and chaos erupted in the rear infantry ranks well before the first of their volleys. Caught in a crossfire, Barón Totil von Schwarzenberg was forced to divide his attention between fore and rear formations, and ultimately to withdraw from the pass in order to preserve his remaining manpower.

The retreat from Mariazell was not only a dispiriting humiliation for Moravia’s First Army. It was also a major propaganda coup for Castinus. The victory of Frédéric de Avesnes-Hohenschwangau, near a place where the Blessed Virgin Mary had appeared in medieval times, was attributed to the intervention of the Holy Mother of God Herself: God was on the side of the Pope. Pamphlets and lithographs depicting the battle, of the glorious victory of Pope Castinus 2. and Frédéric de Avesnes, and of the Mother of God herself scattering the troops of the Moravian infidels, were quick to appear in Western presses.

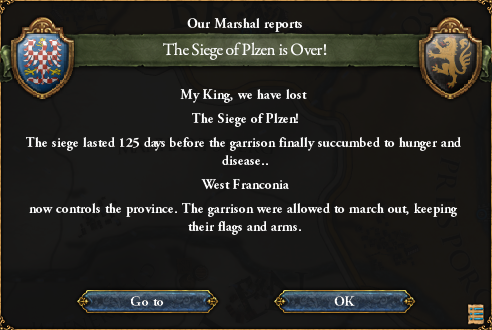

The news of Barón Totil’s loss at Mariazell moved the Kráľ to mobilise the Second Army under the command of Hrabě Mojmír z Otradovic, with the Crown Prince as his lieutenant-general. Mojmír moved the Second Army southwest toward Plzeň to head off the Papal Armies. But another Rhenish-Franconian army, under the command of Bouchard de Foix, had already crossed the march from Bayern into the Czech lands. The fight was already at Moravia’s doorstep.

By the time Mojmír had set up the lines, the West Franconians were already prepared for them. Bouchard de Foix, knowing he was outnumbered, instead set up his armies to hold their positions as long as possible. Mojmír, seeing from this that he was expecting reinforcements, did his level best to root the West Franconians out of their entrenched positions before that could happen.

He was not successful. Once again the armies of Frédéric de Avenses-Hohenschwangau, having broken off from the main Papal army on a forced march northward, came to the aid of their countrymen. And once again Mojmír had to fend off over ten thousand pieces of artillery in support of a large bulk of infantry forces nearly twice as strong. Bouchard de Foix was spared from the fire; and Mojmír was forced to beat another humiliating retreat from Plzeň.

The Kráľ was powerless to stop the aftermath. The brutalities of warfare were visited upon the innocents of Plzeň after its surrender four months later. The West Franconians stole, burned, tortured, raped and murdered at will. Those who were lucky, who were able to escape the city and flee eastward, brought with them gruesome tales. Some recounted the fates of an entire church full of laypeople, including the elderly and children who were herded inside, which was then set to the torch by soldiers under the command of Bouchard de Foix. Others recounted how West Franconian soldiers would collect the ears, noses and tongues of their victims as trophies.

~~~

‘Měrćink,’ called Hrabja Rodźisław.

A slender man with hard blue eyes appeared before the Hrabja. ‘Yes, môj Pán.’

‘I want you to take Drježdźany’s armies and move them southward to assist Moravia in her fight against the Pope. Alone we stand no chance; together, there might be one.’

Lieutenant-General Peč Měrćink of the Drježdźanian Army bowed and made his way out into the courtyard. Then Hrabja Rodźisław looked in silent plea to his wife, Lydija—heavily pregnant with their child. She nodded to him with, as it appeared, reluctant assent. Then Rodźisław called for Awgust Jakobic. The elderly steward appeared in the room.

‘It is likely,’ said the Sorbian Hrabja, ‘that the West Franconians will not stop with Plzeň. We will be attacked as well. And it grieves me that Fojtsko may be first on the block.’

Awgust shuddered slightly, but his face betrayed no other emotion.

‘Our only chance,’ said the Hrabja, ‘lies in joining with Moravia to repel the invaders. I have already sent Měrćink south to join our armies to theirs. I would like you and Dźiwona to see to the personal safety of my Hrabjanka. Head for Velehrad: I place my only hope now in God and you. I cannot risk her or our child falling into the hands of the němcy; we’ve seen what mercies they are capable of.’

‘Môj Pán, it shall be done as you command.’

Awgust Jakobic, Dźiwona and their daughter Anet left Budyšín that very evening, along with Dźiwona’s heavily pregnant ‘sister’ Lejna (in fact the Hrabjanka Lydija).

Anet—a rather awkward and ungainly girl, big for her age, with a tousle of walnut-brunette hair—might have been something of a source of exasperation to her mother when it came to doing household chores well. But she understood the fine points of diplomacy. She knew exactly whom it was they were escorting out of Budyšín, and why. And she also knew the look of pain on her father’s face when he told them the order to leave their home and flee southeast for Velehrad.

‘Why are we not staying?’ asked the thirteen-year-old of her father. ‘I understand the need to get her to safety, but why can we not stay and resist?’

Awgust took his daughter’s shoulders and looked into her deep brown eyes. ‘I have not known many good nobles in my life, Anetka,’ he told her. ‘Those who ruled us prior to the Rychnovských were brutal, hard men: happy to use the whip on us like horses or cattle, and eager to take from us even that which we didn’t have. The Rychnovských are different. They fear God. If there is any hope for a godly future in the Sorbian lands, it lies with them, I am sure of it. I could do nothing to save môj Pán’s firstborn son from plague. But I can do something to save his wife, and the child within her, now. If I do not obey môj Pán’s order now, then I am no Jakobic and no true Sorb.’

Anet Jakobica nodded. ‘I understand, Father. I think.’

The Jakobic family—augmented by one pregnant noblewoman—reached Velehrad. Lydija Rychnovská gave birth in April of 1594 to a baby boy in the travellers’ hospital by the cathedral. The fair-skinned, brown-browed little lad, the new heir to the throne of Drježdźany, was named Wojen Rychnovský, for he had been born in wartime. And not only Awgust but also his daughter Anetka kept solemn vigil for mother and child. The steward’s daughter was learning as well, the honour of her family’s duties, and the solemn bond which linked them to the fate of the Rychnovských.

~~~

The armies of Drježdźany arrived in Praha just in time. The forces of Mojmír z Otradovic were engaged against those of Frédéric de Avesnes-Hohenschwangau in full pitch, and the entire valley was filled with the heavy reek and pall of gunsmoke and lead shot. Peč Měrćink lifted the bugle and ordered the charge from the north against the dim shadows of the Franconian lines, and the two thousand Sorbs with him lifted their voices in battle-cry as they ran down headlong against the němcy.

In addition, a smaller number of Silesians from Poznań arrived from the northwest. Together, the Moravians, Silesians and Sorbs managed to fight Frédéric to a standstill… and then to a retreat. At long last, the Moravians scored a solid victory against the West Franconians and forced them to withdraw from Praha.

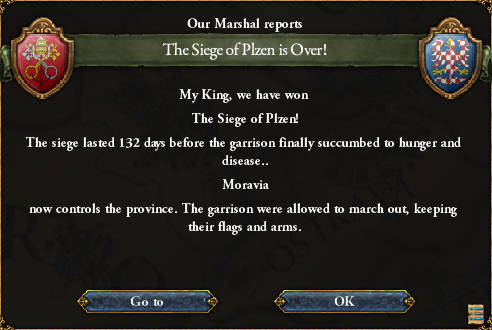

The victory had cost enough. The concentration of force on the chief Bohemian city had indeed left Drježdźany undefended. The Rhenish-Franconians were able to capture Fojtsko and Hłohow, and they visited atrocities similar in nature, if not in scope, upon those two settlements, to those they had in Plzeň. Many Sorbs followed the Jakobicow, fleeing southward from the Rhenish-Franconians across the Moravian border into cities like Hradec, Praha and Lehnice. On the other hand, however, the Moravians did manage to liberate Plzeň from the grip of the West Franconians. It took, again, just over four months of effort—the city was back in Moravian hands by June of 1594.

- 2