Chapter XXVI

The Power Vacuum Left by the Death of Manuel III

The 27 year reign of John X abruptly shattered with the short three year reign of his brother, Manuel III. And, in terms of historical record—he accomplished little. Granted, he was the pawn of many powerful nobles who sought to advance their own interests at the behest of a puppet emperor, his short reign signaled the end of the centralization reforms of John X and marked the beginning of the “Long Regency.” Manuel’s son, Constantine, enthroned as Constantine XII, was but three years of age when he ascended the throne of Augustine and Constantine the Great. In his place, powerful political coalitions emerged to rule in his stead.

The power vacuum left with the death of Manuel can be broken down into three principal groups: the feudal aristocracy in Greece and Trebizond (the main conspirators against John X), the first military triumvirate of Nikolaus Melissinos, Ambrosios Gabras, and Admiral Niccolo Fernio (a Genoan naval officer in the service of the empire), and John’s old court headed by his wife, the widowed Empress Sophia. Sophia became the tutor and de facto ruler upon the ascension of Constantine XII. Her popularity with the people was a difficult matter for the aristocrats to circumnavigate, and the military divided along their loyal lines: those loyal to Melissinos were loyal to Sophia because Melissinos was a favourite of the empress, those soldiers who aligned with Gabras (in Greece) were loyal to the feudal lords of Macedonia and Athens, and the navy tipped the balance of power depending on the favor and direction of the wind.

In this sense, the powerful coalitions that emerged with the death of Manuel were those loyal to the aristocracy and those loyal to John’s old court. It was the military, however, that wielded the true power. Neither the aristocrats nor Sophia held any sway without the loyalty of the Roman Army. And as stated, the army conveniently associated with the different coalitions as long as it suited them. Like the triumvirates before them, particularly those at the closure of the republican era before Julius Caesar crossed the Tiber and entered Rome—the triumvirate military order was centered in various localities of the empire. Where Caesar, Lepidus, and Pompey all had their bases of separated bases of operation, so too did Melissinos, Gabras, and Fernia. Melissinos concentrated his forces at the capital of Constantinople. Ambrosios Gabras was located in Trebizond, and Admiral Fernio had the primary Roman fleet based in Athens. Greece and Trebizond were in the hands of the aristocratic powers, and insofar that Fernio had his primary command in Athens, was, starting in 1531, moderately aligned with the interests of the despotates if not only out of his own self-interest.

Indeed, the Greek aristocrats attempted to enhance their opportunities to seize absolute power in Constantinople by swaying Fernio to completely align with them. Great Domestic John of the Morea, the principle aristocrat who stood against the Empress Sophia in the first stage of the Long Regency, envisioned a two-pronged assault on the capital. Viewing himself as a liberator against the Palaiologoi plight, John advanced the notion that Gabras was to march from Trebizond and head towards Constantinople from the east. He and his army would be helped by the Roman navy stationed in the city on the crossroads itself, it would mutiny in favor of Fernio’s command—who, after all, was the de facto head of the maritime fleet even though his proper command was stationed in Athens to serve as a quick response against the Mamluks, Turks, and Italians all the same. Meanwhile, the Greek and Albanian nobles would muster an army in Thessaly and march on Constantinople from the west. The Roman navy, headed by Fernio, would screen the Greco-Albanian advance from the coast, and cross the Bosporus and break through the city defenses along the Golden Horn to force the capitulation of the city and usher in the new age of the patricians.

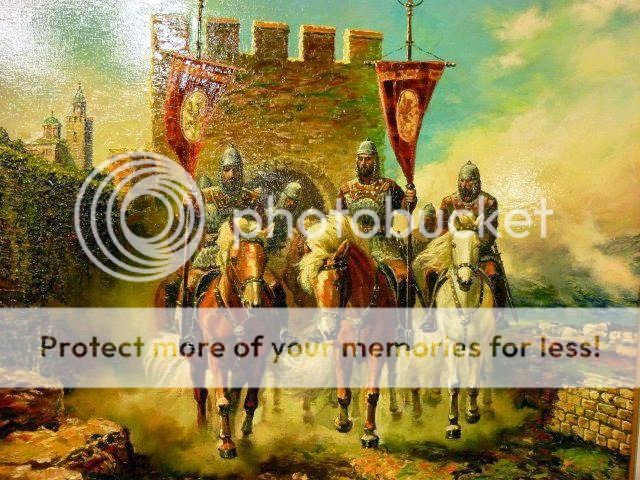

Strategos Ambrosios Gabras, general of the east, was the principle military officer in service of the aristocracy during the Long Regency. He contended with his principle rival, Nikolaus Melissinos, as the most important and powerful of the Roman generals during this period. Some say, however, he held power over the aristocracy.

Strategos Ambrosios Gabras, general of the east, was the principle military officer in service of the aristocracy during the Long Regency. He contended with his principle rival, Nikolaus Melissinos, as the most important and powerful of the Roman generals during this period. Some say, however, he held power over the aristocracy.

The plan, of course, was naturally suspect. While the aristocrats were aligned in seeking a decentralized authority, few thought that John was ripe for the title of emperor. Indeed, many preferred a weak emperor who would be their puppet instead of another potential centralizer and reformer. Great Domestic John, insofar that he was the intellectual and manipulator of the push against the young Constantine XII and his steward empress-regent, Sophia, was deemed as a potential liability by some of the more notable aristocratic families, particularly the Komnenoi in Trebizond, who felt that if any of the aristocratic families that deserved to replace the Palaiologoi as emperors—it was them! As such, quarrel fell over the conspirator tables and no moves were to be made for over a year. Plus, despite Gabras’ close association with the Komnenoi, his oath was in the service of the emperor. Some of the more weary aristocrats viewed the general with suspicion, especially since they understood that the military held the real balance of power. For some, including Great Domestic John, there was a push to place officers in command of the Roman armies who were otherwise fanatically loyal (under the thumb) of the aristocratic forces to prevent the possibility of being betrayed at the high watermark.

At the same time, the royal court in Constantinople was not out of touch with the realities of the ambitions of the aristocrats and the dissident military forces outside the walls of Constantinople. Empress Sophia, ever the plotter and planning, had an extensive spy network throughout the confines of the empire that had been established under John X to gauge support for his centralizing reforms. At a minimum of once a month, she held private meetings with her spies who would return to Constantinople to report on the developments in Greece and Trebizond.

Some have said that Sophia was interested in the throne for herself. This is a possibility, although unlikely. In the history of Rome, powerful women had always played a prominent role in Roman politics. Before the rise and fall of Theodora, there was the ambition and talent of the Empress Aelia Placidia who not only ruled as a regent herself, but was the prominent power broker in the conflict between Bonifacius and Aetius in the Western Roman Empire. Aelia Ariadne, an eastern empress, factored prominently in two co-reigns after the western half of the empire had fallen. Sophia, standing in the same tradition as many powerful women before her, sat upon a throne during a regency and wielded direct and absolute power over the court and direction of the empire. Her affair with Melissinos was out of love, surely enough, but also served as a political move to ensure the loyalty of Rome’s most prominent military general during the era of the Long Regency. Their love bound the court and forces in Constantinople together. And, as her spies continually indicated to her—she held a considerable advantage in that her forces were concentrated, and her rivals divided.