The Griffin and the Pride

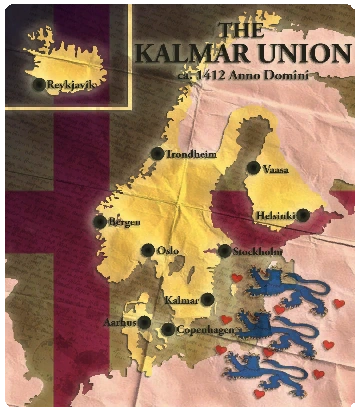

Part I: The Failure of Kalmar

The ousting of Erik would lead not to a restoration of Hanseatic control over the Nordic realms, instead the old King had gathered to him the remnants of the Victual Brothers and set them loose against his enemies. At this point this seems to have included mostly everyone with a port between Bergen and Nöteborg. He had settled in Visborg, the castle of Visby that he himself had ordered built some thirty years, and there he had brought his sole daughter and heir as well as his morganatic wife Cecilia.

Of her we know least of all, for she is excluded from the Greifskrönike apart from the one line that states that she went with Erik to Gotland, and later one that states that she remained at Visborg when Margrete sailed to Denmark. It’s believed that she was the Cecilia Jensdatter that’s mentioned in some contracts whereby Jensdatter buys land in Sjaelland during the 1430’s, but the only proof of this is that no other Cecilia is mentioned among the Danish nobility at the time. What is known is that hers and Erik’s marriage caused something of a scandal. When the King was told to seek another wife the Danish Council expected him to seek the daughter of some foreign Lord or Prince, preferably one of their choice. Cecilia was but a mistress, a secondary wife (

frille) and hers being unable to become a proper consort tells us that she was of relatively low station. Holding a frille wasn’t improper, but from such a relation no heir could be born, though the children had some legal protection and rights to inheritance.

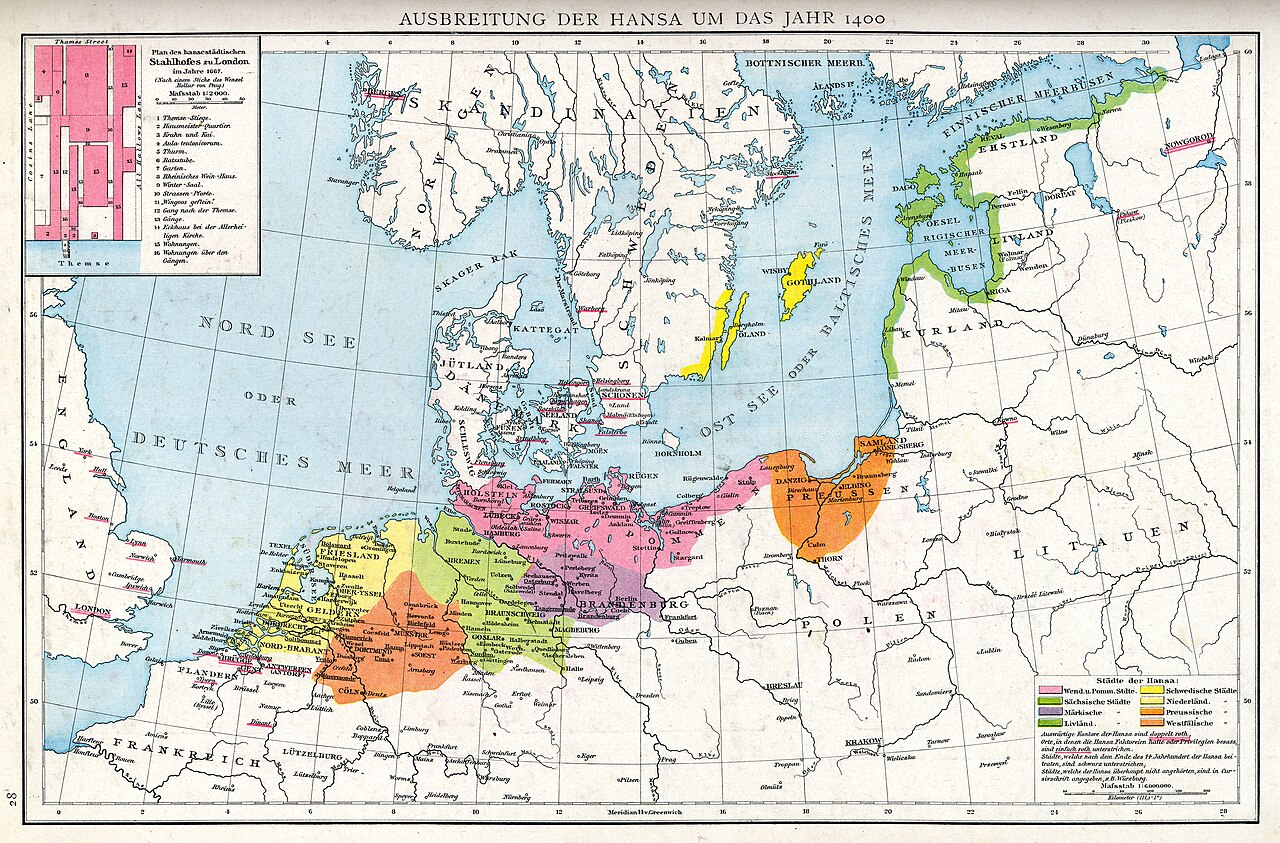

The old exile would in time gather a great treasury in Visby, since neither he nor his pirates had much to spend it on. Gotland was isolated from the rest of the Baltic Sea and relied only upon its hinterlands and what spoils could be brought back to the island. Erik did attempt to conspire against his nephew but found little luck. He sent emissaries to the Lowlands and to England, as well as to Poland, Pomerania and even to Novgorod. Only the Dutch traders did offer some support, for they had come into conflict with their German counterparts regarding the herring that had moved their spawning from the Danish Sound to the North Sea. Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy and master of most of the Lowlands supported their efforts half-heartedly, but the effort would mark the start of the friendship between Burgundy and Margrete II.

Philip the Good, Penultimate Duke of Burgundy

The Dutch-Hanseatic War of 1438-1441 has commonly been viewed as a Dutch victory, but this is perhaps due to later hindsight. What the Dutch did manage was to break the Hanseatic grain monopoly over the Baltic Sea, as well as granting equal fishing rights in the North Sea but the prize was hefty as the Dutch basically had to pay for these rights through reparations. Erik saw now real gain from the conflict, and after he would become increasingly irrelevant outside his impact upon trade, and now the Dutch could be counted among his foes.

Of their final years at Visborg we have little substantial knowledge. Whether it was done by Margrete’s expressed wishes or by mere caution by its author, Paulus Gothicus, who had been present during those years as a Franciscan brother in Visby, the Greifskrönike glosses over Erik’s last years. Most tales that have come down to us were based on folktales that gained particular popularity during the 18th and 19th centuries and tells of a king resigned to his fate, but much concerned with that of his daughters. These stories were perhaps in turn influenced by Marlowe’s account in his

Margareth II, supposedly based on accounts by Charles I & V in later years. The scene at Erik’s death bed in Margareth II is likely the one deepest ingrained in public consciousness, where a young Margrete waits by her father’s side as he is dying and promising him that he shall “rest one day in Denmark, at the side of your wife, my mother, the good Queen Philippa. Your enemies vanquished; your people finally freed from the Usurper’s yoke”. Cecilia then cries out as the King draws his final breath, and the scene ends.

Christopher had his own troubles, though most of the blame for them should be laid at Erik’s feet. Whilst the wars against Holstein dragged on, more and more land had been divested unto the Danish nobility. The peasantry faced raised taxes and, worse, increasing efficiency in collecting them. When the common folk finally had had enough, they rose, and some knights or lesser noblemen in Jylland joined them. Christopher answered with force, failed and had to grant liberties to any rebel who would put down their arms and return home. Only when their numbers were depleted could he manage to defeat them. The conflict is notable for two reasons – it saw the first usage of wagon forts in Danish histories, showing the rather quick spread of that practice out of Bohemia even to the Nordic Realms, but more impactful was Christopher’s slow but sure response in curtailing the free peasantry of Denmark.

The liberties granted would be revoked one after another as Christopher grew in strength, but he would remain an impoverished, curtailed ruler. Sweden would only accept a purely personal union with Denmark, declaring their right to freely elect and evict kings as in days of old. Bonde, initially remaining as Regent was granted most of Finland, but soon he’d be pushed away from his position by Swedish rivals and would ever after remain hostile towards Christopher, naming him weak and treacherous. To compound the issues facing the young King, the 1440’s saw a series of poor harvests in all of the Nordic realms and the Swedes branded him

Barkkonung (lit. Bark-King) since they were forced to mix tree bark with their grains to keep starvation at bay.

Contemporary portrait of Christopher von Neumarkt-Pfalz

Christopher’s rule would be a troubled one. He befriended the Hansa, though their friendship faltered rather soon after the conclusion of the Dutch-Hanseatic War, especially after his marriage to Dorotea of Brandenburg in 1445. Dorotea was the daughter to the overlooked Johann von Brandenburg-Kulmbach, commonly known as John the Alchemist, but the marriage had been negotiated by her uncle Friedrich II, Marcher-Lord-Elector of Brandenburg, and both Friedrich and his brother Albrecht Achilles were hostile towards Lübeck. The issue between lord and merchant was the same as before. The 15th century saw kings and princes grow in power and the ancient liberties – granted or invented after the fact – of the cities guarded a great source of wealth that would cause those lords to grow even greater. Whilst Christopher never went as far as to reintroduce the Sound Dues, he instead attempted to empower the Danish church and granted them rights to bring their exports directly to German cities, rather than to use Hanseatic go-betweens. The Hansa protested and went as far as to enter into negotiations with Erik. This would in time prove to become their and Christian I’s ruin.

On the matter of Erik and his piracy Christopher did little. He may have attempted to ally himself with the German Order who’d once driven the Victual Brothers out and might perhaps be able to do so again, but if so naught came of it. When an emissary from Lübeck came to Köbnehavn to plead for the Danish king to retake his own island and safe-guard the Baltic Sea, it is said that Christopher responded “even uncles must make a living”. The response might tell us more of Christopher’s reputation than his actual character. Posterity has been rather unkind to Christopher, particularly as he was kin to the man he supplanted. He would make one effort of curbing his uncle and travelled to Gotland to meet with Erik in late 1446. Erik was promised several castles in Denmark should he cease his piracy and leave Gotland, and the two promised to withhold from fighting for a year before meeting again. Instead they would both die, Erik in December of 1447 and Christopher in January of 1448, just as their truce ended.

The coincidence of their death, for no convincing proof that any hand moved against them has ever been presented, has provided several fiction writers with material to work with. The common culprit pointed to is of course Christian I himself for he saw the greatest gain from Christopher’s death, but the notion that this young nobleman recently come to Holstein from Oldenburg would have such sway in Denmark, not to say the isolated island of Gotland do stretch into the incredulous. There are other varieties of the story, whereby Christopher’s death was natural but Erik was poisoned by a Swedish emissary from Bonde, the Hansa or even his own daughter. There has been some who have called for the exhumation of their bodies in recent years to finally put the matter to rest, but the Crown has thus far been reluctant to allow any such desecration of their kin.

Margrete’s position was far from safe. Erik’s death was apparently sudden, despite his sixty-five years, and she but a maiden of seventeen, untried and inexperienced. Apparently his death was kept secret for a while, giving Margrete time to contact several members of the two City Councils as well as the captains of the ships in harbor and having secured their allegiance she imprisoned several persons of note. They would be kept as her guests, and would later be hosted by Cecilia, securing the loyalty of their families and peace in Visby. Only when Margrete had made sure that the garrison in Visborg and the city itself was loyal did she announce Erik’s death and let toll the church bells. The King was embalmed and put to rest, temporarily, in the Church of our Beloved Lady Mary. When this was managed she would make use of her father’s hoard and showered both soldier, sailor and city with gold and patronage. “Why would I sit upon my wealth, like some hen upon her egg, or even as some worm in elder days. No, let them have it, for I am naught without them. Neither gold nor precious stones shall buy me a throne, but loyal subjects may”, she answered Cecilia as her step-mother asked if it was prudent to squander so much gold.

In Denmark there was no heir to take the reins. Christopher’s death broke the line of descent from Valdemar and Margrete I in Denmark, for only Margrete now remained of their descendants. Margrete sent emissaries to Köbnehavn, Stockholm and Trondheim, who also carried with them the news of Erik’s death but though they were admitted and allowed to speak the nobles of all three realms remained resolutely against her assuming any throne. What troubled them was that though the Councils could agree that Margrete would not ascend, they couldn’t find a common candidate acceptable to all three realms and negotiations were dragging on. The Danes had settled on Christian von Oldenburg, nephew and heir of Adolf von Holstein-Rendsburg. For Denmark he was a good choice and his elevation would finally end the long and ruinous conflict with Holstein over Slesvig. The Swedes were reluctant to follow. What good had the union brought them? They had overlooked by Margrete, neglected by Erik and impoverished by Christopher, they stated. They had suffered grievously under these Germans and instead chose one of their own. Karl Knutson Bonde came rushing back to Stockholm from his Finnish holdings and was crowned at the Stones of Mora even before Christian. Karl seems to have been convinced, and had convinced the Swedes, that if they chose him as their ruler then Denmark would follow to keep the union intact. They were wrong.

Contemporary portrait of Christian von Oldenburg

Norway would, as seems all too common, have the worst of it when both Denmark and Sweden called for them to elect their candidate. The Norwegian Council chose Christian as their King in 1449 but that same summer Bonde travelled to Trondheim and summoned the Norwegian estates to him, there he was raised as king as well, splitting the realm in two. Military action never came of it since the Swedes proved hesitant to follow Bonde when his predictions had failed, and instead the two kings would meet in Halmstad in 1450 to settle the matter. There Karl would abandon his Norwegian throne in return for an agreement that whosoever of the two kings survived the other would be his heir. The treaty heavily favored Christian, being twenty years younger than Bonde. The matter of Gotland, having been a Swedish land conquered by Valdemar IV, would be left for the future.

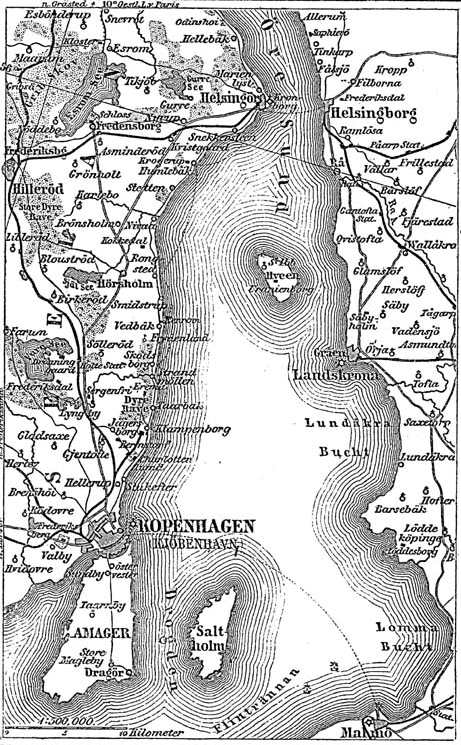

In the Greifskrönike, it’s claimed that Christian sent envoys to Visby, asking for Margrete’s hand in marriage. Marlowe’s version has the young King himself sail to Visby to propose to her instead. Her refusal is countered with “then, if you shall not have me as husband, I shall claim from you what poor dowry you may bring another, and the Griffin shall be drowned beneath the sea”. Whether or not this happened at all is disputed. The Danish Council seems to have insisted that Christian wed Dorotea, who’d been granted large estates upon Christopher’s death and was key to Christian being able to rule self-sufficiently. Regardless, Christian would return with an army in early 1451.

Margrete would hold the castle for two months before unexpected relief arrived. Bonde landed a force of some four thousand knights north of Visby and besieged the besiegers, claiming that Christian had betrayed the Treaty of Halmstad. Christian, faced with an outbreak of measles in the city, agreed to withdraw and was allowed to return home to Denmark. Now Margrete instead found herself besieged by a Swedish army, but Bonde instead proposed a marriage and an alliance between the two. Margrete would remain in control of Visby and would cease her piracy, and in a year’s time she would travel to Stockholm and wed Karl. The forty-three year old king had been married once before to a Swedish noblewoman who’d given him several daughters, but she’d died in 1446. Margrete accepted and Karl left her with a force of Swedish knights “to keep his betrothed safe, should the German usurper return”. According to Marlowe the young lady was reluctant, not necessarily to Karl himself but to the way the arrangement had happened. “I will not go to my husband’s home at sword-point, nor shall I go to his bed a beggar. Mine is the blood of kings and queens, and I shall stand next to him an equal. Or die the spinster.”

The commander of the Swedish force was Gustav Karlson, member of the Swedish Council and married to Karl’s half-sister and he soon summoned his wife to Visborg alongside her young son from her previous marriage, Sten Sture. Gustav is mentioned frequently in the Greifskrönike as Margrete’s

“most beloved friend and subject” and it seems that she won over both him and his wife early on. At least they did nothing to stop Margrete from entering into negotiations with Lübeck during that summer and both Gustav and Sten would be granted Danish lands following her invasion of Denmark the following year.

The Hanseatic League at ca 1400 A. D. The Hansa would gradually devolve into separate entities during the 15th Century. Cities underlined once in red held so called Vittens

, whilst those underlined twice held Kontors

It was upon the Eve of Saint Lucy in 1451 that three ships laid anchor outside Visby harbor. They’d sailed out of Lübeck some three weeks earlier, led by Johann Kollman, one of the city’s four mayors and a trusted envoy on behalf of the Hansa. Kollman had been present almost a decade earlier when Christopher III negotiated a treaty between the Lübeck and her Dutch rivals, and he was present again when the Danish Council appointed Christian, giving Lübeck’s approval to him ascending to the Danish throne against promises of peace towards Lübeck, hostility towards the Lowlands and to finally drive Erik and his pirates out of Visby. Three years had now passed since Christopher’s death and little had been done. Adolf yet lived, but no clear plan for the succession of Slesvig had been arranged. Dutch cogs and hulks still passed unmolested through the Danish Sound, and whilst Erik had died Gotland remained outside of Christian’s control. His withdrawal the previous year had been an utter embarrassment, and worse, a financial disaster. Christian was, like his predecessors, strapped for funds, and he had borrowed heavily to build a fleet as well as to hire mercenaries. When the Hansa had come to collect after his retreat, he threatened to reestablish the Sound Dues if he was not given reprieve. The Hansa refused and Christian paid, but only months later he started reinforcing his castles at Helsingborg and Helsingör.

Marlowe makes much of Kollman’s surprise s meeting and Kollman’s surprise of “

finding this flower of youth, this northern star, in place of the foeman of the old and stern king” but any such notion can be disregarded. The meeting wasn’t made on a whim but had been carefully planned through intermediaries, in this case in Pomeranian Stralsund under the auspices of the Lübecker ally Otto Voge. It was in Stralsund where the ships had stopped whilst sailing east as well, and Voge again got the chance to play the statesman as three out of the four current Pomeranian dukes met there with him and Kollman to give their support to Margrete. Only Pomerania-Stettin held out, or more likely weren’t even invited due to their connections to the Hohenzollerns in Brandenburg. Ties between Berlin and Köbnehavn had been growing as of late and this alliance troubled Lübeck, for Friedrich II Hohenzollern was not a friend of theirs. However, it troubled the Pomeranian Griffins even more. Brandenburg claimed that all of Pomerania was but an erstwhile vassal of theirs. The deal struck in Stralsund would later become known as the

Golden Accord, whereby the dukes agreed to favor their Hanseatic cities in return for the promise of aid against Brandenburg. The alliance against Denmark was not written down, but Voge would later write to Margrete to ask her favor and to remind her of his “old friendship to her, when he brought her kinsmen into his home and brought their aid to her”.

The Greifskrönike sheds some light upon that day, describing how Margrete, alongside the Gute and German councils of Visby, its abbots and priests met with Kollman as he came ashore. The words and promises claimed to have been spoken are more difficult to evaluate and has to be measured by what happened after Kollman returned to Lübeck. Margrete claims that the Hansa granted their support against the promise of restoring their privileges in Denmark and holding to Valdemar’s promise, though Slesvig would be Danish leaving Christian with Holstein only, and a sworn oath to never again raise the Sound Due. They would then raise an army for her that would march upon Jylland, and their fleet would sail to aid hers at the Sound. The vast fleet of Gotland was gathered in Visby and set sail towards Denmark on the 21th of May in 1452, and upon that day the Northern Pivot was set in motion.