Reader poll - coda for the war years, or on to the after-war years? Be warned, after-war is probably going to start with an analysis of the Reich's internal politics over the course of the war, so either way, you're looking at a couple fairly dry posts (though frankly, I think the pre-game work on this AAR's still the best part).

Eine Geschichte des Grossdeutsches Reich - Germany/Road to Doom's Day

- Thread starter c0d5579

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Give us up to 1950 and give us at least one surprise, but don't go twist mad  What would be cool was if Hitler were say... assassinated, and an Albert Speer-ian Nationalist Technocracy became the new government - causing Himmlers hardline faction to break off and a reich civil war...

What would be cool was if Hitler were say... assassinated, and an Albert Speer-ian Nationalist Technocracy became the new government - causing Himmlers hardline faction to break off and a reich civil war...

But I digress and assume to be able to dictate!

But I digress and assume to be able to dictate!

War years coda, please.

I vote for that as well.

7. The War Years: Conclusion

On March 1, 1948, the return of soldiers from Britain and Africa began in earnest. The British government was sufficiently stable to allow Reich troops to begin withdrawing to the mainland; however, this was not, as many had hoped, for immediate demobilization. The Fuehrer had decided to preserve Germany's military at a high state of establishment. Privately, he pointed out that the number of generals was rapidly eclipsing the number of divisions - drawing divisions down to cadre was fine in theory, but the officers needed men to lead.

He himself did little to stem the tide of promotion: the victory parade celebrating the destruction of the Western Powers began at the Garrison Church in Potsdam, where fifteen years prior, the Fuehrer had spoken to the Reichstag beside President Hindenburg, and stretched all the way to Berlin's Olympic Stadium - an unimaginably long distance of thirty kilometers' march, with the lead units departing the Garrison Church the night prior by torchlight and arriving at the stadium as the sun rose. The parade dwarfed the previous million-man Sowjet victory parade. At its culmination, in another torchlit ceremony, the Fuehrer celebrated the British victory by naming another forty-three Reichsheer and Waffen-SS field marshals, thirteen grand admirals, and two air marshals. The Fuehrer had, in fifteen years, created half as many marshals as in all German history prior to his rise. The marshals thus created were decorated as lavishly as they had been promoted, with the Grand Cross of the Iron Cross being awarded for the first time under the new Reich. The awardees were:

Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt (Poland, 1937)

Field Marshal Fedor von Bock (Russia, 1942)

Field Marshal Julius Ringel (Russia, 1943)

Hauptgruppenfuehrer Paul Hausser (Scandinavia, 1943)

Field Marshal Erich von Manstein (Italy, 1946)

Field Marshal Erwin Rommel (France, 1947)

Grand Admiral Erich Raeder (Britain, 1948)

Field Marshal Walter Model (Egypt, 1948)

Field Marshal Heinz Guderian (India, 1948)

It was an illustrious list, to be sure, but there remained the problem of peacetime employment both of these men and their armies. It was a problem which Germany had given little consideration to, outside of certain offices of the SS, including the Reich Settlement Main Office, which fell under Heydrich's purview.

What, then, had these men accomplished? True, Germany was free of Versailles, and had revenged all of the wrongs of 1918, but new problems arose. Germany held an empire stretching pole-to-pole, and from Ghent to Grozny, an empire which even the Fuehrer was forced to admit was largely useless, assimilated mainly to discomfit the Reich's enemies. They had accomplished this through a series of daring gambles resting on the idea of reaching a goal by any means available before the defense had a chance to organize. When this plan was executed according to these principles - such as throughout the Balkans - the world considered the German army the finest in the world. In circumstances ill-fitted to the German method of waging war, such as Italy, losses on the scale of the Great War could be expected.

There were solid foundations to this method of warmaking, however. Starting in the 1930s, the German military had begun working from the premise of being badly outnumbered in any potential conflict, or of the opposition being entrenched in the world's most modern fortifications. To this end, the Reich had established its armed forces on the principle of achieving local superiority, and requiring that the Reichswehr be the best-trained, best-equipped force which it could possibly be, invoking Voltaire's maxim that "God is not on the side of the big battalions, but on the side of those who shoot best." Certain weapon systems epitomized this mentality. Foremost among these was the PzKpfW V "Panther" tank.

Figure 90: A column of Panthers advances through Russia

The Panther was the foundation of the Reichsheer's armored formations from the Sowjet War to the invasion of Britain, and in the form of the Standardpanzer, it continued to serve until the early 1950s. Its success was due to a number of features, foremost of which, as with all of the German military, was crew training. Beyond excellent, well-trained vehicle crews, though, the Panther was a vehicle developed in perfect tune with the doctrine by which it was employed, and equipped to overpower any vehicle of any opposing nation. Reservations which the Reich leadership had felt regarding tanks in first Russia, then France, and finally Britain were overwhelmed by the reality of the Panther's superiority on battlefield after battlefield. Even when the Panther was poorly employed, such as in Rome or London, it is hard to imagine another armored vehicle performing the same duties as well.

The Panther's main armament was a long-barreled 75mm smoothbore cannon, the KwK42/L70, which proved capable of penetrating the armor of its most notable opponent, the much scarcer Sowjet T-34, through its glacis plate (the thick, sloped armor plate on the front of any tank) at 300 meters, and through any point in its turret armor at 2000 meters - beyond the Sowjet tanks' theoretical maximum range! An emphasis on superior gunnery in German armored crews exacerbated this problem, with men like SS-Hauptsturmfuehrer Balthasar Woll, once an enlisted tank gunner with Michael Wittmann, achieving confirmed kills against the Sowjet T-34 at ranges of up to 3000 meters. This combination of crew and armament superiority partially explains why the German advance through the Sowjet Union was so rapid: the Sowjets simply did not know how to respond, and even when they were able to lure German armored forces into confrontations nominally favorable to them, the German superiority in crew training generally won out - it was an armored force, after all, which broke through the Sowjet mountaineers' defenses north of Vladivostok and linked up with General Ringel to end the Sowjet War in 1943.

Figure 91: Parachutists fighting in southern Sweden, 1944

Ringel's parachutists were another area in which the Reichswehr was markedly superior to any of its rivals. Though the Sowjets had pioneered the use of air-deployed soldiers in the 1930s, they had failed to grasp their significance, and only Germany had developed any significant airborne assets by the early 1940s. They were under-employed during the Reich's early wars, with a few detachments participating as regular infantry in Poland and Hungary, and launched a massive, successful invasion of Crete in 1942, but the Sowjet war truly saw them come into their own, with a mass landing along the Dnieper which allowed the rapid advance of the armored forces deep into the Ukraine. The airborne forces were continuously upgraded during the war, but generally their armament from the Sowjet War onward remained fairly constant. The average soldier was armed with an MP43 rifle or variant thereof and a sidearm, the average squad equipped with at least two disposable anti-tank rockets and two machine guns, and the average platoon equipped with a long-range radio which allowed it to contact higher artillery assets. In peacetime conditions, they thought nothing of marching upwards of fifty kilometers in a day for days on end; this paid off in circumstances such as Africa or the isolation of Vladivostok, where generals like Student and Ringel were able to persuade them to continue operations where even mechanized units would have begged for a halt.

Figure 92: DRMS Ernst Thaelmann during Mediterranean trials, 1944

If Germany's land forces were founded on the parachute and the Panther, the Reichsmarine rested on a tripod of battleships, aircraft carriers, and submarines, the so-called "balanced fleet" that the British had hoped to trap Germany into building so that it could be destroyed by their own home fleet. As it happened, the Fuehrer's decision to ignore the Anglo-German Naval Agreement proved prescient. It allowed the construction of more and larger vessels, and in the mid-1940s, Germany's aircraft carrier technology especially leapt forward. The primitive, flush-decked Graf Zeppelin-class carriers of the 1930s were abandoned in favor of heavier, better-equipped ships which were in turn capable of launching heavier, better-equipped aircraft, generally the Luftwaffe's hand-me-downs; naval aviation design would not become fully independent until Goering's death. In comparison, the Reichsmarine generally felt that they had a perfectly designed set of weapons in the Bismarck-class battleship and the Scharnhorst-class battlecruiser. With a few updates such as strengthened belt armor, improved fire control, and the Seetakt radar system, they remained virtually unchanged through twelve years of war. They proved themselves in engagements in the Mediterranean against the Italians, and again in the Channel against the Royal Navy, but increasingly the Reichsmarine became aware that the future of warfare rested with the carriers and, perhaps, the submarines.

Figure 93: Type XXI U-Boat at sea, unknown location, 1945

The main submarine used by the Reichsmarine during the 1940s was the Type XXI U-Boat, which, unlike previous models of submarine anywhere in the world, was designed to operate submerged for its entire patrol. It operated successfully against the French Navy during the Australian handover, and even in American waters during the temporary hostilities between the United States and Germany in 1947-1948. Even more than the surface vessels, the Type XXI saw improvements over the submarines of the Great War. These improvements were partially crew comfort - a freezer, a shower, a washroom - and partially technological - advanced passive acoustic sensors, a Zuse machine in each boat, and a sophisticated loading-firing system that would allow it to fire all of its torpedo tubes in the time once required to fire a single tube. The ability to fire and flee undetected made the Type XXI an exceptionally dangerous opponent, and it would not be until the mid-1950s and the advent of nuclear power that an adequate replacement could be found.

Figure 94: Surviving Me-262 "Weiss-1" of JG7, Berlin-Tempelhof, 2006

The Luftwaffe suffered from two major drawbacks in its war planning. The first was that, unlike the Reichsheer and Reichsmarine, it was seemingly impossible for the Luftwaffe to achieve local superiority, even in the Sowjet War. Sowjet anti-aircraft guns seemingly outnumbered Sowjet tanks; even so, the Luftwaffe, not the Reichsmarine, claimed the first battleship of the war years, the Marat at Leningrad. The second deficiency was compounded by the first. Despite Goering's tremendous political influence, the clear superiority of its aircraft, and the best efforts of its officers, the Luftwaffe was never able to maintain air parity in the West, against Britain's Royal Air Force. Even during the British war, when the RAF was flying antiquated propeller-driven, cannon-armed Spitfires against the Reich's cutting-edge Kurzbogen missile-armed Me-262 jets, there were simply so many British aircraft that they could not be swept clear until the Reichsheer overran the British Isles - as General Galland exclaimed, "We have to land sometimes, and the damned Tommies are there when we do!" It was not until the postwar reforms and the "Grossere Staffel" movement, spearheaded by Galland and Field Marshal Kesselring, would establish the Luftwaffe at sufficient size that this difficulty would never again arise.

These, then, were the weapons and men who fought the wars; however, their planning processes have not been thoroughly outlined. Much has been made, especially by the British historian B.H. Liddell-Hart, of the influence of British prewar thought on German doctrine during the war years; however, this influence exists largely in the minds of Hart and his supporters. Even in Field Marshal Guderian's own writings, which Hart claims clearly show his influence, no distinct philosophy in the Clausewitzian manner emerges. What emerges is the idea of a fighting spirit, rather than a system. The foundation of this spirit is the offensive mentality, and the desire to seize any opportunity presented to achieve the objective. The momentary removal of enemy troops from one section of the line to reinforce another, for instance, may be ruthlessly exploited, such as happened in Warsaw in 1937. Similarly, on the national level, the political isolation of a small neighboring country is practically an invitation for intervention in its internal affairs by the Reich by this viewpoint.

The establishment of local superiority and the ruthless exploitation of any opportunity presented are the foundations of the offensive spirit inculcated by Guderian and his followers; however, it had its risks. A common "what if?" exercise involves the airborne forces - what if, at any point during the war, the vulnerable air transports had been intercepted by enemy aircraft? It is unlikely that they would have been able to achieve their objectives at all, and if they had, considerable loss of life would ensue. Similarly, Guderian especially was guilty of rushing forward ahead of his supporting elements and leaving himself vulnerable to encirclement and destruction. In Russia especially, units would occasionally find themselves encircled by Russian troops even as they attempted to encircle the enemy themselves.

Similar problems permeated the Reichsmarine. The achievement of local superiority could only occur in a battle such as that of the Thames by denuding Germany's entire naval frontage, and this is why subsidiary actions against the Americans were fought in Normandy-Brittany and Sicily. The Reichsmarine was capable of overwhelming any one enemy in any one location, given sufficient planning, but such success came at a steep price, which is to say the exposure of the Reich to landing anywhere else along its rather extensive coastline and the inadequate protection of the vulnerable supply convoys to Indochina and Africa.

In the 1930s and 1940s, then, German military policy was one of calculated gambling. The Fuehrer guessed, correctly as it turned out, that the Western powers would not intervene until it was too late for them to stop the eastward, northward, and southward expansion of the Reich, and his military staff followed his lead, gambling over and over again on the superiority of German arms and soldiers against a succession of opponents. If any one of those opponents had proven to be more than the Reich had been prepared to face, especially in Russia, it is chilling to think of what the present political situation might be. Captured Sowjet documents make it clear that Germany was to be subjected to the most brutal of occupations, with no clear end save perhaps a Communist-controlled puppet government and the wrecking of the Reich's most treasured institutions (for more information, see Suworoff, Icebreaker and related works).

Figure 95: The Reich, European Economic Union, African Economic Union, and Asian Economic Union spheres after de-colonialism, 1950

---

Next up - The Occupation (1948-?), including decolonialism, the death of Goering, and an update on that fellow in the basement of the RLM building with his clicky machines.

EDIT - Two points before I go back to playing the game in very close to real time (multiple nations with thousand-plus division armies equals bog-down).

1 - That's an actual flying Me-262 replica, though not the "real" White-1 of JG7, which is a two-seater you can apparently pay to ride.

2 - The map shows it badly because Kazakhstan and NatChi have the same map color, but NatChi has NOT become a super-monster in central Asia, that's Kazakhstan.

On March 1, 1948, the return of soldiers from Britain and Africa began in earnest. The British government was sufficiently stable to allow Reich troops to begin withdrawing to the mainland; however, this was not, as many had hoped, for immediate demobilization. The Fuehrer had decided to preserve Germany's military at a high state of establishment. Privately, he pointed out that the number of generals was rapidly eclipsing the number of divisions - drawing divisions down to cadre was fine in theory, but the officers needed men to lead.

He himself did little to stem the tide of promotion: the victory parade celebrating the destruction of the Western Powers began at the Garrison Church in Potsdam, where fifteen years prior, the Fuehrer had spoken to the Reichstag beside President Hindenburg, and stretched all the way to Berlin's Olympic Stadium - an unimaginably long distance of thirty kilometers' march, with the lead units departing the Garrison Church the night prior by torchlight and arriving at the stadium as the sun rose. The parade dwarfed the previous million-man Sowjet victory parade. At its culmination, in another torchlit ceremony, the Fuehrer celebrated the British victory by naming another forty-three Reichsheer and Waffen-SS field marshals, thirteen grand admirals, and two air marshals. The Fuehrer had, in fifteen years, created half as many marshals as in all German history prior to his rise. The marshals thus created were decorated as lavishly as they had been promoted, with the Grand Cross of the Iron Cross being awarded for the first time under the new Reich. The awardees were:

Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt (Poland, 1937)

Field Marshal Fedor von Bock (Russia, 1942)

Field Marshal Julius Ringel (Russia, 1943)

Hauptgruppenfuehrer Paul Hausser (Scandinavia, 1943)

Field Marshal Erich von Manstein (Italy, 1946)

Field Marshal Erwin Rommel (France, 1947)

Grand Admiral Erich Raeder (Britain, 1948)

Field Marshal Walter Model (Egypt, 1948)

Field Marshal Heinz Guderian (India, 1948)

It was an illustrious list, to be sure, but there remained the problem of peacetime employment both of these men and their armies. It was a problem which Germany had given little consideration to, outside of certain offices of the SS, including the Reich Settlement Main Office, which fell under Heydrich's purview.

What, then, had these men accomplished? True, Germany was free of Versailles, and had revenged all of the wrongs of 1918, but new problems arose. Germany held an empire stretching pole-to-pole, and from Ghent to Grozny, an empire which even the Fuehrer was forced to admit was largely useless, assimilated mainly to discomfit the Reich's enemies. They had accomplished this through a series of daring gambles resting on the idea of reaching a goal by any means available before the defense had a chance to organize. When this plan was executed according to these principles - such as throughout the Balkans - the world considered the German army the finest in the world. In circumstances ill-fitted to the German method of waging war, such as Italy, losses on the scale of the Great War could be expected.

There were solid foundations to this method of warmaking, however. Starting in the 1930s, the German military had begun working from the premise of being badly outnumbered in any potential conflict, or of the opposition being entrenched in the world's most modern fortifications. To this end, the Reich had established its armed forces on the principle of achieving local superiority, and requiring that the Reichswehr be the best-trained, best-equipped force which it could possibly be, invoking Voltaire's maxim that "God is not on the side of the big battalions, but on the side of those who shoot best." Certain weapon systems epitomized this mentality. Foremost among these was the PzKpfW V "Panther" tank.

Figure 90: A column of Panthers advances through Russia

The Panther was the foundation of the Reichsheer's armored formations from the Sowjet War to the invasion of Britain, and in the form of the Standardpanzer, it continued to serve until the early 1950s. Its success was due to a number of features, foremost of which, as with all of the German military, was crew training. Beyond excellent, well-trained vehicle crews, though, the Panther was a vehicle developed in perfect tune with the doctrine by which it was employed, and equipped to overpower any vehicle of any opposing nation. Reservations which the Reich leadership had felt regarding tanks in first Russia, then France, and finally Britain were overwhelmed by the reality of the Panther's superiority on battlefield after battlefield. Even when the Panther was poorly employed, such as in Rome or London, it is hard to imagine another armored vehicle performing the same duties as well.

The Panther's main armament was a long-barreled 75mm smoothbore cannon, the KwK42/L70, which proved capable of penetrating the armor of its most notable opponent, the much scarcer Sowjet T-34, through its glacis plate (the thick, sloped armor plate on the front of any tank) at 300 meters, and through any point in its turret armor at 2000 meters - beyond the Sowjet tanks' theoretical maximum range! An emphasis on superior gunnery in German armored crews exacerbated this problem, with men like SS-Hauptsturmfuehrer Balthasar Woll, once an enlisted tank gunner with Michael Wittmann, achieving confirmed kills against the Sowjet T-34 at ranges of up to 3000 meters. This combination of crew and armament superiority partially explains why the German advance through the Sowjet Union was so rapid: the Sowjets simply did not know how to respond, and even when they were able to lure German armored forces into confrontations nominally favorable to them, the German superiority in crew training generally won out - it was an armored force, after all, which broke through the Sowjet mountaineers' defenses north of Vladivostok and linked up with General Ringel to end the Sowjet War in 1943.

Figure 91: Parachutists fighting in southern Sweden, 1944

Ringel's parachutists were another area in which the Reichswehr was markedly superior to any of its rivals. Though the Sowjets had pioneered the use of air-deployed soldiers in the 1930s, they had failed to grasp their significance, and only Germany had developed any significant airborne assets by the early 1940s. They were under-employed during the Reich's early wars, with a few detachments participating as regular infantry in Poland and Hungary, and launched a massive, successful invasion of Crete in 1942, but the Sowjet war truly saw them come into their own, with a mass landing along the Dnieper which allowed the rapid advance of the armored forces deep into the Ukraine. The airborne forces were continuously upgraded during the war, but generally their armament from the Sowjet War onward remained fairly constant. The average soldier was armed with an MP43 rifle or variant thereof and a sidearm, the average squad equipped with at least two disposable anti-tank rockets and two machine guns, and the average platoon equipped with a long-range radio which allowed it to contact higher artillery assets. In peacetime conditions, they thought nothing of marching upwards of fifty kilometers in a day for days on end; this paid off in circumstances such as Africa or the isolation of Vladivostok, where generals like Student and Ringel were able to persuade them to continue operations where even mechanized units would have begged for a halt.

Figure 92: DRMS Ernst Thaelmann during Mediterranean trials, 1944

If Germany's land forces were founded on the parachute and the Panther, the Reichsmarine rested on a tripod of battleships, aircraft carriers, and submarines, the so-called "balanced fleet" that the British had hoped to trap Germany into building so that it could be destroyed by their own home fleet. As it happened, the Fuehrer's decision to ignore the Anglo-German Naval Agreement proved prescient. It allowed the construction of more and larger vessels, and in the mid-1940s, Germany's aircraft carrier technology especially leapt forward. The primitive, flush-decked Graf Zeppelin-class carriers of the 1930s were abandoned in favor of heavier, better-equipped ships which were in turn capable of launching heavier, better-equipped aircraft, generally the Luftwaffe's hand-me-downs; naval aviation design would not become fully independent until Goering's death. In comparison, the Reichsmarine generally felt that they had a perfectly designed set of weapons in the Bismarck-class battleship and the Scharnhorst-class battlecruiser. With a few updates such as strengthened belt armor, improved fire control, and the Seetakt radar system, they remained virtually unchanged through twelve years of war. They proved themselves in engagements in the Mediterranean against the Italians, and again in the Channel against the Royal Navy, but increasingly the Reichsmarine became aware that the future of warfare rested with the carriers and, perhaps, the submarines.

Figure 93: Type XXI U-Boat at sea, unknown location, 1945

The main submarine used by the Reichsmarine during the 1940s was the Type XXI U-Boat, which, unlike previous models of submarine anywhere in the world, was designed to operate submerged for its entire patrol. It operated successfully against the French Navy during the Australian handover, and even in American waters during the temporary hostilities between the United States and Germany in 1947-1948. Even more than the surface vessels, the Type XXI saw improvements over the submarines of the Great War. These improvements were partially crew comfort - a freezer, a shower, a washroom - and partially technological - advanced passive acoustic sensors, a Zuse machine in each boat, and a sophisticated loading-firing system that would allow it to fire all of its torpedo tubes in the time once required to fire a single tube. The ability to fire and flee undetected made the Type XXI an exceptionally dangerous opponent, and it would not be until the mid-1950s and the advent of nuclear power that an adequate replacement could be found.

Figure 94: Surviving Me-262 "Weiss-1" of JG7, Berlin-Tempelhof, 2006

The Luftwaffe suffered from two major drawbacks in its war planning. The first was that, unlike the Reichsheer and Reichsmarine, it was seemingly impossible for the Luftwaffe to achieve local superiority, even in the Sowjet War. Sowjet anti-aircraft guns seemingly outnumbered Sowjet tanks; even so, the Luftwaffe, not the Reichsmarine, claimed the first battleship of the war years, the Marat at Leningrad. The second deficiency was compounded by the first. Despite Goering's tremendous political influence, the clear superiority of its aircraft, and the best efforts of its officers, the Luftwaffe was never able to maintain air parity in the West, against Britain's Royal Air Force. Even during the British war, when the RAF was flying antiquated propeller-driven, cannon-armed Spitfires against the Reich's cutting-edge Kurzbogen missile-armed Me-262 jets, there were simply so many British aircraft that they could not be swept clear until the Reichsheer overran the British Isles - as General Galland exclaimed, "We have to land sometimes, and the damned Tommies are there when we do!" It was not until the postwar reforms and the "Grossere Staffel" movement, spearheaded by Galland and Field Marshal Kesselring, would establish the Luftwaffe at sufficient size that this difficulty would never again arise.

These, then, were the weapons and men who fought the wars; however, their planning processes have not been thoroughly outlined. Much has been made, especially by the British historian B.H. Liddell-Hart, of the influence of British prewar thought on German doctrine during the war years; however, this influence exists largely in the minds of Hart and his supporters. Even in Field Marshal Guderian's own writings, which Hart claims clearly show his influence, no distinct philosophy in the Clausewitzian manner emerges. What emerges is the idea of a fighting spirit, rather than a system. The foundation of this spirit is the offensive mentality, and the desire to seize any opportunity presented to achieve the objective. The momentary removal of enemy troops from one section of the line to reinforce another, for instance, may be ruthlessly exploited, such as happened in Warsaw in 1937. Similarly, on the national level, the political isolation of a small neighboring country is practically an invitation for intervention in its internal affairs by the Reich by this viewpoint.

The establishment of local superiority and the ruthless exploitation of any opportunity presented are the foundations of the offensive spirit inculcated by Guderian and his followers; however, it had its risks. A common "what if?" exercise involves the airborne forces - what if, at any point during the war, the vulnerable air transports had been intercepted by enemy aircraft? It is unlikely that they would have been able to achieve their objectives at all, and if they had, considerable loss of life would ensue. Similarly, Guderian especially was guilty of rushing forward ahead of his supporting elements and leaving himself vulnerable to encirclement and destruction. In Russia especially, units would occasionally find themselves encircled by Russian troops even as they attempted to encircle the enemy themselves.

Similar problems permeated the Reichsmarine. The achievement of local superiority could only occur in a battle such as that of the Thames by denuding Germany's entire naval frontage, and this is why subsidiary actions against the Americans were fought in Normandy-Brittany and Sicily. The Reichsmarine was capable of overwhelming any one enemy in any one location, given sufficient planning, but such success came at a steep price, which is to say the exposure of the Reich to landing anywhere else along its rather extensive coastline and the inadequate protection of the vulnerable supply convoys to Indochina and Africa.

In the 1930s and 1940s, then, German military policy was one of calculated gambling. The Fuehrer guessed, correctly as it turned out, that the Western powers would not intervene until it was too late for them to stop the eastward, northward, and southward expansion of the Reich, and his military staff followed his lead, gambling over and over again on the superiority of German arms and soldiers against a succession of opponents. If any one of those opponents had proven to be more than the Reich had been prepared to face, especially in Russia, it is chilling to think of what the present political situation might be. Captured Sowjet documents make it clear that Germany was to be subjected to the most brutal of occupations, with no clear end save perhaps a Communist-controlled puppet government and the wrecking of the Reich's most treasured institutions (for more information, see Suworoff, Icebreaker and related works).

Figure 95: The Reich, European Economic Union, African Economic Union, and Asian Economic Union spheres after de-colonialism, 1950

---

Next up - The Occupation (1948-?), including decolonialism, the death of Goering, and an update on that fellow in the basement of the RLM building with his clicky machines.

EDIT - Two points before I go back to playing the game in very close to real time (multiple nations with thousand-plus division armies equals bog-down).

1 - That's an actual flying Me-262 replica, though not the "real" White-1 of JG7, which is a two-seater you can apparently pay to ride.

2 - The map shows it badly because Kazakhstan and NatChi have the same map color, but NatChi has NOT become a super-monster in central Asia, that's Kazakhstan.

Last edited:

Brazil. Narvik is owned by Britain, controlled by Brazil. I forgot about the Narvik beachhead until the peace treaty was being negotiated, and the Brazilians landed troops during the London Conference. I strongly suspect that garrison duty sucks for those guys.

Part VI: The Occupation

1. From War to Peace

The Reich had lived under a military junta during the war years, with the War Cabinet and War Minister von Blomberg controlling the vast majority of economic production from 1937 to 1948. As a result, historical focus has largely been on their deeds and actions during the war, rather than on the evolution of the Economic Cabinet during the same period.

The Economic Cabinet had indeed changed radically; the 1940 retirement for health reasons of Economic Minister Franz Xaver Schwarz had led to his replacement as Economic Minister by Walther Funk, a journalist and one of the few leading Party members with no combat service in the Great War, despite a brief service as an infantryman before a medical discharge in 1916. Nevertheless, he was viewed within the Party as a keen economic observer, and from January of 1933 had served in a number of sensitive spots as the Fuehrer's direct economic representative. Funk spent the early War Years, before Schwarz's resignation, as the coordinator of the disposition of the economic remains of Poland and the Balkan states. As a consequence, he was well-acquainted with economic policy throughout the occupied region, a key recommendation for any economic minister in the post-war Reich.

Additionally, General Ott had been relieved of his duties as chief of intelligence during this period to return to Japan as ambassador - not due to any failing on his part, but because of the importance and sensitivity of the Japanese connection during the last days of the war, while a de-facto alliance existed. He would be recalled with the collapse of the Japanese government after their own peace settlement, but in the meantime, he was incapable of managing the Reich's intelligence apparatus. His replacement was a member of the Canaris faction of the Abwehr, Major-General Hans Oster. The Fuehrer had doubts about Oster's loyalty, as his private papers show, and a poor relationship with the man as Oster's own journal indicates, but Oster had, along with a number of other officers including Major-General Georg Thomas, drawn up the Reichswehr's post-war infrastructure development plans for the eastern territory, and as such he was a vital addition to the Economic Cabinet.

It is a sign of how far Field Marshal Goering had fallen from the political center of the Reich that he had relinquished all control of the Four-Year Plan to the Economics Minister in 1940, after its completion, and the Second, Third, and Fourth Four-Year Plans contained minimal subsidies for his pet Hermann-Goering-Werke steel plants. Goering's withdrawal from Reich politics was concordant with the discrediting of the "Wilhelmine" school of foreign policy, and his successors as Commander-in-Chief of the Luftwaffe lacked his drive to dabble in all aspects of Reich society, including economics. They were content with filing their requests through the same channels as the rest of the Reichswehr, which maintained its connection to the Economics Ministry through General Thomas and his Economic Planning Staff, and General of Artillery Becker and his Research Staff.

Finally, in February 1948 at the end of the Western War, Field Marshal von Blomberg quietly tendered his resignation as war minister. He had led the German military through the greatest period of conquest in its history, and felt that such strains, combined with an active field command, were sufficient for more than a decade. The Fuehrer agreed, and asked him to name a replacement. Von Blomberg surprised everyone concerned by naming a Waffen-SS officer as his replacement: Paul Hausser. Hausser was the most respected armored commander in the entirety of the Reichswehr, including regular Reichsheer generals, and as a retired Reichsheer general, he was more palatable than most of the Waffen-SS leadership. Von Blomberg's posthumously released journal also indicates that he had foreseen the outcome of the struggle over eastern settlement between regular Reich justice and the police forces, and wished the Reichsheer to maintain at least a formal independence from the Party, a cause to which Hausser was sympathetic as a former regular general.

Von Blomberg became the military administrator of Russia, and Paul Hausser became the first Reichsmarschall, a special promotion lifting him to the level of his previous nominal superior Reichsfuehrer-SS Heinrich Himmler and a cabinet-level position. Grand Admiral Raeder became Reichsadmiral Raeder; Field Marshal Goering became Reichsmarschall Goering (a largely honorary promotion; Goering did not even protest when, during his life, his successor at the Luftwaffe, Robert Ritter von Greim, also became Reichsmarschall). The promotion was handed out more sparingly after these initial promotions, to recognize that the holder held a cabinet-level responsibility and was equivalent to a cabinet minister in all respects.

Figure 96: SS Marshal Hausser on his way to take control of the War Ministry, 1948

In many ways, Hausser was an excellent choice on von Blomberg's part - he believed strongly that the military was and should always be separate from the Party, and had argued persuasively for a separation of the Waffen-SS and the General SS. Indeed, one of the first reforms which Hausser pushed through as Reichsmarschall and War Minister was the expansion of the role of the Waffen-SS from a strictly German force to one which bound together the disparate national entities beneath Reich protection. Thus, he ordered the creation of Dutch, Belgian, and even French divisions. Surprisingly, the response from the east was much greater than that from the west; this may perhaps be due to the announcement of the colonization terms.

The Reich government faced a quandary to the east. On the one hand, it controlled a vast territory with thus-far untapped resources. On the other, it had generously released into independence all of the Sowjet subjects east of the Urals, and as much of sub-Saharan Africa as was feasible for self-rule at any given moment. Thus, the portions of Europe and the Middle East under direct Reich rule expected that this would be due to them, too. They were, of course, mistaken. This space was the "living space" which the Fuehrer had prophesied Germany would need to survive. To supervise this, the Fuehrer had several tools at his disposal. The first was the Eastern Ministry, under Alfred Rosenberg, which had supervised the dismantling of post-Sowjet Asia. The second, of course, was the Reichsheer, though the generals balked at the idea of an indefinite garrison force. The third was an office of the SS, the Race and Settlement Office (RuSHA, for Rasse-und-Siedlingsheithauptamt - trans.). Seeing the diminuition of his power elsewhere, Reichsfuehrer Himmler strongly pushed the third option, and for reasons of his own, the Fuehrer agreed. One suspects that he viewed the existing structures as very slender reeds for providing himself an heir, and that perhaps he viewed the SS as a potential wellspring of a successor; however, this is supposition based on subsequent events.

The Fuehrer had another problem, a huge military due its discharge papers in many cases. The two of them were mated together in a solution borrowed from the ancient Romans - communities of veterans were to be established throughout the east, under RuSHA guidance and placement, and were to "Germanize" Russia as far as could be reached. This concept had, of course, been presented in one form or another as far back as 1939; however, the difference was that subsidiary communities of acceptable local populations were to be attached to each German settlement, with the goal of eventually splicing the two strands, German and culturally German (Volksdeutsch, a hard-to-translate concept that varied in implementation from location to location - trans.) and cementing the east as a German possession. Certain incentives were offered - for a given time of service, a soldier was entitled to either a cash pension or land and seed implements, and for those willing to settle in the east, garrison service in the east counted as double service time, Waffen-SS service counted as double service time, spouses and children counted as various additional fractions of service time.

There was, of course, resistance to German settlement, in the form of an increase in banditry throughout the east. The man best suited for dealing with this was SS-und-Polizei-Hauptgruppenfuehrer Reinhard Heydrich, who had developed a sterling record during first his establishment of a Reich-wide political police force in the 1930s (sullied only by his tangential involvement in the Blomberg-Fritsch Affair of 1938), then his wartime service as a fighter pilot (the Fuehrer grounded him after his twenty-third air-to-air kill in Sowjet Russia), and finally as the Fuehrer's wartime Balkan viceroy. Heydrich's military arm was Waffen-SS General Erich von dem Bach, but he was handicapped by the 1930s agreements regarding Reich justice and extrajudicial processes. Thus began the struggle between Heydrich and Walther Buch's 1946 replacement as Reich Minister of Justice, Roland Friesler. It could not have been worse-timed; international events worsened the Reich's internal stresses.

During the occupation of Britain, many of the United Kingdom's leading politicians had been able to abscond from Reich justice, using the confusion of the Scots-Welsh-Irish border situation as an opportunity to flee the island. In May of 1948, these men reappeared en masse, led by a distant cousin of the Royal Family, Louis Lord Mountbatten, to proclaim that the British Commonwealth still existed in exile, its capital in Delhi. The Fuehrer was, of course, furious - but he had also just begun the great work of Germanizing the East. Despite the blatant confrontational attitude of the Indian puppet and their American masters, the Reich's leadership stubbornly refused to be drawn into yet another war. It was a thoroughly unpopular decision, but the Fuehrer declared that the settlement policy must come first.

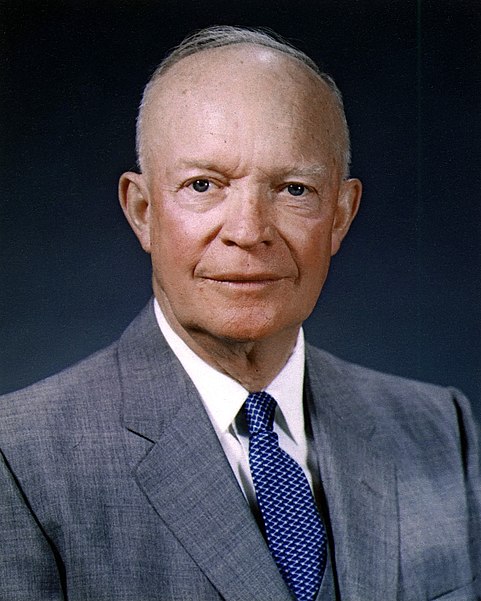

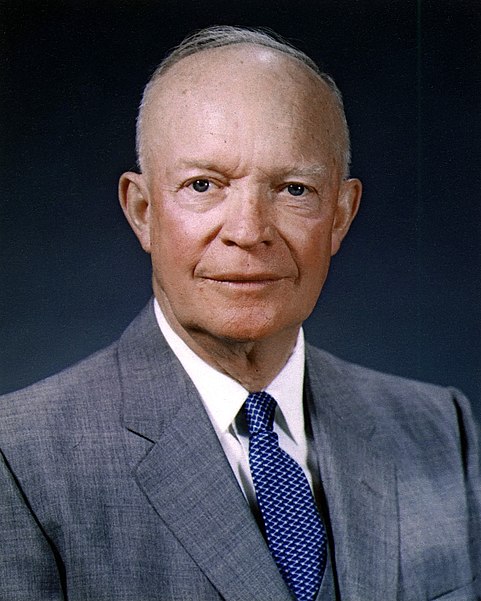

Figure 97: Edward R. Murrow and American journalist and German "expert," William L. Shirer, Berlin, 1949

The settlement policy itself came under fire shortly thereafter, a consequence of American "fact-finding" journalists who had been allowed access to Russia to show that the Reich had behaved throughout in a civilized manner. These men were shown the handiwork of Stalin and his cronies - the Belomor Canal, the Volga-Don Canal, the penal camps of the Solovetsky Islands - which some among them steadily insisted on attributing to German deeds rather than their obvious Stalinite origin. Foremost among these were the American rabble-rousers Cronkite of the United Press and Murrow of the Central Broadcasting Service, both men who had broadcast from London during the Battle of London; however, their American audiences remained unaware of the clear slant of their so-called "unbiased reporting*." It is small wonder that neither would be invited back for many years despite their outsize influence on the American public.

Nevertheless, a small percentage of Germans believed the reports of these lying scribblers, and for the first time since 1933, Germany seemed to be on the verge of serious internal turmoil. Friesler of the Justice Ministry reported a steady increase in politically-motivated crime from May to June of 1948, and only steadfast work by Ministers Friesler and Goebbels, and the steadfast application of police power by Heydrich's police successor, Heinrich Mueller, brought the situation back under control. Even then, elections for the Reichstag were delayed until July of 1949 by emergency decrees all the way down to the local level.

The Fuehrer stunned the newly-seated Reichstag of 1949, filled though it was with the Party faithful, used to the Fuehrer's lightning-bolt proclamations, by announcing that the invasion of Spain had commenced on September 1, 1949. Why he chose to invade Spain has never been fully established; the operation itself was so swift that it does not even merit inclusion in the War Years, and was mostly notable for General Student's surprise drop into the Aragonese hinterland and subsequent march on Madrid. Most historians believe that this was due to the persistent influence of the Spanish emigre and Fascist leader, Francisco Franco Bahamonde, who promised the Fuehrer a Spanish force for Hausser's new Waffen-SS if he could be reinstated. Unfortunately, Franco had few followers remaining in Spain; disillusioned, the Fuehrer ordered the Spanish Partition, undoing efforts at reuniting Spain since the 1400s.

Figure 98: The results of the 1949 Spanish Partition - from northwest to south, Galicia, Castille, Euskadi, Catalonia, and Andalusia

The Spanish Partition was most popular with the various regional movements that succeeded the unified government, though even there, most of the regional independence movements had been left-leaning socialists who felt exceptionally awkward receiving their freedom from Madrid from the Fuehrer. It was intensely unpopular in the Spanish-speaking portion of the Americas, where there was a sudden upwelling and outpouring of support for the "Mother Country" even though Spanish rule in the New World had been a miserable history of oppression and misrule devoted strictly to the enrichment of a small section of Castilian society - much like Moscow's rule of the Sowjet Union, three hundred years early. These countries made their protests felt in Berlin, and again, there was a small section of German society which believed their protests had weight.

Figure 99: Minister of Justice Roland Friesler, the eventual loser of the struggle between police and judiciary

All of this necessitated a close cooperation between police and judicial officials, and delayed the inevitable resolution of the conflict between the police and the lawyers. Even Minister Friesler saw that a demand for clarification from the Fuehrer of the role of each would be misplaced, for though he was sure that it would strengthen his hand personally, it would weaken the Reich fundamentally. Thus, it was not until May of 1950 that the Fuehrer was comfortable enough with the Reich's internal situation to name the Reichsfuehrer-SS, Heinrich Himmler, to the position of Interior Minister, and give his subordinates their rein to prosecute the eastern settlement policy without interference from the Ministry of Justice, whose authority would stand only within areas which the Reichsfuehrer and his police subordinates had deemed were both fully Germanized and peaceful - one more incentive for the eastern communities to remain pacific and not rise in riot every time someone spoke German in Poland.

It was also in 1950 that the settlement program bore its first fruits; in August, Ostfuehrer Heydrich felt sufficiently confident in its success to proclaim former Poland and the Baltic states as eligible for full Reich membership; with the lifting of occupation rule in those territories, the level of banditry decreased substantially and their populations were allowed to begin applying for full membership as Reich citizens, rather than remain as a subject people. Since these territories had always been either adjacent to or ruled by Germany historically, the procedure of Germanizing the regions was relatively painless.

This period also saw the elevation of Field Marshal von Manstein to Reichsmarschall and the creation of the African Ministry, which had quietly worked to divest Germany of as many regional powers as could be deemed prudent. Von Manstein had been the center of the Reichswehr party disgruntled at Hausser's elevation, and his promotion to a parallel position and distraction with the political and engineering problems of Africa largely defused this potential source of trouble. The Africans were quite willing to listen to a man with von Manstein's tremendous planning talent and military credentials, and the result was today's African Economic Union. The Reich held onto Kamerun, South Africa, and portions of the Congo, since regional leadership which could be trusted to follow Reich guidance proved impossible to locate.

Figure 100: The African Economic Union after the last independence grants, 1950

Thus, as the 1950s began, Germany's position was as benevolent leader of an economic sphere which dominated three continents and had research outposts on Antarctica, allies on South America, and no particular interest in North America or Australia. It could safely be described, in the Englishman Shakespeare's words, of bestriding the world like a colossus. However, there is evidence that even at this early date, the Fuehrer may have been thinking beyond that sphere.

* This is one of the few times where it is difficult for me to present Keppler's writing; Cronkite and Murrow belonged to the finest tradition of American journalism and their exposition of both German occupation and Stalin's cruelty took incredible courage given that they began drafting said work while still in Hitler's Germany. - W. Fredlund, trans.

1. From War to Peace

The Reich had lived under a military junta during the war years, with the War Cabinet and War Minister von Blomberg controlling the vast majority of economic production from 1937 to 1948. As a result, historical focus has largely been on their deeds and actions during the war, rather than on the evolution of the Economic Cabinet during the same period.

The Economic Cabinet had indeed changed radically; the 1940 retirement for health reasons of Economic Minister Franz Xaver Schwarz had led to his replacement as Economic Minister by Walther Funk, a journalist and one of the few leading Party members with no combat service in the Great War, despite a brief service as an infantryman before a medical discharge in 1916. Nevertheless, he was viewed within the Party as a keen economic observer, and from January of 1933 had served in a number of sensitive spots as the Fuehrer's direct economic representative. Funk spent the early War Years, before Schwarz's resignation, as the coordinator of the disposition of the economic remains of Poland and the Balkan states. As a consequence, he was well-acquainted with economic policy throughout the occupied region, a key recommendation for any economic minister in the post-war Reich.

Additionally, General Ott had been relieved of his duties as chief of intelligence during this period to return to Japan as ambassador - not due to any failing on his part, but because of the importance and sensitivity of the Japanese connection during the last days of the war, while a de-facto alliance existed. He would be recalled with the collapse of the Japanese government after their own peace settlement, but in the meantime, he was incapable of managing the Reich's intelligence apparatus. His replacement was a member of the Canaris faction of the Abwehr, Major-General Hans Oster. The Fuehrer had doubts about Oster's loyalty, as his private papers show, and a poor relationship with the man as Oster's own journal indicates, but Oster had, along with a number of other officers including Major-General Georg Thomas, drawn up the Reichswehr's post-war infrastructure development plans for the eastern territory, and as such he was a vital addition to the Economic Cabinet.

It is a sign of how far Field Marshal Goering had fallen from the political center of the Reich that he had relinquished all control of the Four-Year Plan to the Economics Minister in 1940, after its completion, and the Second, Third, and Fourth Four-Year Plans contained minimal subsidies for his pet Hermann-Goering-Werke steel plants. Goering's withdrawal from Reich politics was concordant with the discrediting of the "Wilhelmine" school of foreign policy, and his successors as Commander-in-Chief of the Luftwaffe lacked his drive to dabble in all aspects of Reich society, including economics. They were content with filing their requests through the same channels as the rest of the Reichswehr, which maintained its connection to the Economics Ministry through General Thomas and his Economic Planning Staff, and General of Artillery Becker and his Research Staff.

Finally, in February 1948 at the end of the Western War, Field Marshal von Blomberg quietly tendered his resignation as war minister. He had led the German military through the greatest period of conquest in its history, and felt that such strains, combined with an active field command, were sufficient for more than a decade. The Fuehrer agreed, and asked him to name a replacement. Von Blomberg surprised everyone concerned by naming a Waffen-SS officer as his replacement: Paul Hausser. Hausser was the most respected armored commander in the entirety of the Reichswehr, including regular Reichsheer generals, and as a retired Reichsheer general, he was more palatable than most of the Waffen-SS leadership. Von Blomberg's posthumously released journal also indicates that he had foreseen the outcome of the struggle over eastern settlement between regular Reich justice and the police forces, and wished the Reichsheer to maintain at least a formal independence from the Party, a cause to which Hausser was sympathetic as a former regular general.

Von Blomberg became the military administrator of Russia, and Paul Hausser became the first Reichsmarschall, a special promotion lifting him to the level of his previous nominal superior Reichsfuehrer-SS Heinrich Himmler and a cabinet-level position. Grand Admiral Raeder became Reichsadmiral Raeder; Field Marshal Goering became Reichsmarschall Goering (a largely honorary promotion; Goering did not even protest when, during his life, his successor at the Luftwaffe, Robert Ritter von Greim, also became Reichsmarschall). The promotion was handed out more sparingly after these initial promotions, to recognize that the holder held a cabinet-level responsibility and was equivalent to a cabinet minister in all respects.

Figure 96: SS Marshal Hausser on his way to take control of the War Ministry, 1948

In many ways, Hausser was an excellent choice on von Blomberg's part - he believed strongly that the military was and should always be separate from the Party, and had argued persuasively for a separation of the Waffen-SS and the General SS. Indeed, one of the first reforms which Hausser pushed through as Reichsmarschall and War Minister was the expansion of the role of the Waffen-SS from a strictly German force to one which bound together the disparate national entities beneath Reich protection. Thus, he ordered the creation of Dutch, Belgian, and even French divisions. Surprisingly, the response from the east was much greater than that from the west; this may perhaps be due to the announcement of the colonization terms.

The Reich government faced a quandary to the east. On the one hand, it controlled a vast territory with thus-far untapped resources. On the other, it had generously released into independence all of the Sowjet subjects east of the Urals, and as much of sub-Saharan Africa as was feasible for self-rule at any given moment. Thus, the portions of Europe and the Middle East under direct Reich rule expected that this would be due to them, too. They were, of course, mistaken. This space was the "living space" which the Fuehrer had prophesied Germany would need to survive. To supervise this, the Fuehrer had several tools at his disposal. The first was the Eastern Ministry, under Alfred Rosenberg, which had supervised the dismantling of post-Sowjet Asia. The second, of course, was the Reichsheer, though the generals balked at the idea of an indefinite garrison force. The third was an office of the SS, the Race and Settlement Office (RuSHA, for Rasse-und-Siedlingsheithauptamt - trans.). Seeing the diminuition of his power elsewhere, Reichsfuehrer Himmler strongly pushed the third option, and for reasons of his own, the Fuehrer agreed. One suspects that he viewed the existing structures as very slender reeds for providing himself an heir, and that perhaps he viewed the SS as a potential wellspring of a successor; however, this is supposition based on subsequent events.

The Fuehrer had another problem, a huge military due its discharge papers in many cases. The two of them were mated together in a solution borrowed from the ancient Romans - communities of veterans were to be established throughout the east, under RuSHA guidance and placement, and were to "Germanize" Russia as far as could be reached. This concept had, of course, been presented in one form or another as far back as 1939; however, the difference was that subsidiary communities of acceptable local populations were to be attached to each German settlement, with the goal of eventually splicing the two strands, German and culturally German (Volksdeutsch, a hard-to-translate concept that varied in implementation from location to location - trans.) and cementing the east as a German possession. Certain incentives were offered - for a given time of service, a soldier was entitled to either a cash pension or land and seed implements, and for those willing to settle in the east, garrison service in the east counted as double service time, Waffen-SS service counted as double service time, spouses and children counted as various additional fractions of service time.

There was, of course, resistance to German settlement, in the form of an increase in banditry throughout the east. The man best suited for dealing with this was SS-und-Polizei-Hauptgruppenfuehrer Reinhard Heydrich, who had developed a sterling record during first his establishment of a Reich-wide political police force in the 1930s (sullied only by his tangential involvement in the Blomberg-Fritsch Affair of 1938), then his wartime service as a fighter pilot (the Fuehrer grounded him after his twenty-third air-to-air kill in Sowjet Russia), and finally as the Fuehrer's wartime Balkan viceroy. Heydrich's military arm was Waffen-SS General Erich von dem Bach, but he was handicapped by the 1930s agreements regarding Reich justice and extrajudicial processes. Thus began the struggle between Heydrich and Walther Buch's 1946 replacement as Reich Minister of Justice, Roland Friesler. It could not have been worse-timed; international events worsened the Reich's internal stresses.

During the occupation of Britain, many of the United Kingdom's leading politicians had been able to abscond from Reich justice, using the confusion of the Scots-Welsh-Irish border situation as an opportunity to flee the island. In May of 1948, these men reappeared en masse, led by a distant cousin of the Royal Family, Louis Lord Mountbatten, to proclaim that the British Commonwealth still existed in exile, its capital in Delhi. The Fuehrer was, of course, furious - but he had also just begun the great work of Germanizing the East. Despite the blatant confrontational attitude of the Indian puppet and their American masters, the Reich's leadership stubbornly refused to be drawn into yet another war. It was a thoroughly unpopular decision, but the Fuehrer declared that the settlement policy must come first.

Figure 97: Edward R. Murrow and American journalist and German "expert," William L. Shirer, Berlin, 1949

The settlement policy itself came under fire shortly thereafter, a consequence of American "fact-finding" journalists who had been allowed access to Russia to show that the Reich had behaved throughout in a civilized manner. These men were shown the handiwork of Stalin and his cronies - the Belomor Canal, the Volga-Don Canal, the penal camps of the Solovetsky Islands - which some among them steadily insisted on attributing to German deeds rather than their obvious Stalinite origin. Foremost among these were the American rabble-rousers Cronkite of the United Press and Murrow of the Central Broadcasting Service, both men who had broadcast from London during the Battle of London; however, their American audiences remained unaware of the clear slant of their so-called "unbiased reporting*." It is small wonder that neither would be invited back for many years despite their outsize influence on the American public.

Nevertheless, a small percentage of Germans believed the reports of these lying scribblers, and for the first time since 1933, Germany seemed to be on the verge of serious internal turmoil. Friesler of the Justice Ministry reported a steady increase in politically-motivated crime from May to June of 1948, and only steadfast work by Ministers Friesler and Goebbels, and the steadfast application of police power by Heydrich's police successor, Heinrich Mueller, brought the situation back under control. Even then, elections for the Reichstag were delayed until July of 1949 by emergency decrees all the way down to the local level.

The Fuehrer stunned the newly-seated Reichstag of 1949, filled though it was with the Party faithful, used to the Fuehrer's lightning-bolt proclamations, by announcing that the invasion of Spain had commenced on September 1, 1949. Why he chose to invade Spain has never been fully established; the operation itself was so swift that it does not even merit inclusion in the War Years, and was mostly notable for General Student's surprise drop into the Aragonese hinterland and subsequent march on Madrid. Most historians believe that this was due to the persistent influence of the Spanish emigre and Fascist leader, Francisco Franco Bahamonde, who promised the Fuehrer a Spanish force for Hausser's new Waffen-SS if he could be reinstated. Unfortunately, Franco had few followers remaining in Spain; disillusioned, the Fuehrer ordered the Spanish Partition, undoing efforts at reuniting Spain since the 1400s.

Figure 98: The results of the 1949 Spanish Partition - from northwest to south, Galicia, Castille, Euskadi, Catalonia, and Andalusia

The Spanish Partition was most popular with the various regional movements that succeeded the unified government, though even there, most of the regional independence movements had been left-leaning socialists who felt exceptionally awkward receiving their freedom from Madrid from the Fuehrer. It was intensely unpopular in the Spanish-speaking portion of the Americas, where there was a sudden upwelling and outpouring of support for the "Mother Country" even though Spanish rule in the New World had been a miserable history of oppression and misrule devoted strictly to the enrichment of a small section of Castilian society - much like Moscow's rule of the Sowjet Union, three hundred years early. These countries made their protests felt in Berlin, and again, there was a small section of German society which believed their protests had weight.

Figure 99: Minister of Justice Roland Friesler, the eventual loser of the struggle between police and judiciary

All of this necessitated a close cooperation between police and judicial officials, and delayed the inevitable resolution of the conflict between the police and the lawyers. Even Minister Friesler saw that a demand for clarification from the Fuehrer of the role of each would be misplaced, for though he was sure that it would strengthen his hand personally, it would weaken the Reich fundamentally. Thus, it was not until May of 1950 that the Fuehrer was comfortable enough with the Reich's internal situation to name the Reichsfuehrer-SS, Heinrich Himmler, to the position of Interior Minister, and give his subordinates their rein to prosecute the eastern settlement policy without interference from the Ministry of Justice, whose authority would stand only within areas which the Reichsfuehrer and his police subordinates had deemed were both fully Germanized and peaceful - one more incentive for the eastern communities to remain pacific and not rise in riot every time someone spoke German in Poland.

It was also in 1950 that the settlement program bore its first fruits; in August, Ostfuehrer Heydrich felt sufficiently confident in its success to proclaim former Poland and the Baltic states as eligible for full Reich membership; with the lifting of occupation rule in those territories, the level of banditry decreased substantially and their populations were allowed to begin applying for full membership as Reich citizens, rather than remain as a subject people. Since these territories had always been either adjacent to or ruled by Germany historically, the procedure of Germanizing the regions was relatively painless.

This period also saw the elevation of Field Marshal von Manstein to Reichsmarschall and the creation of the African Ministry, which had quietly worked to divest Germany of as many regional powers as could be deemed prudent. Von Manstein had been the center of the Reichswehr party disgruntled at Hausser's elevation, and his promotion to a parallel position and distraction with the political and engineering problems of Africa largely defused this potential source of trouble. The Africans were quite willing to listen to a man with von Manstein's tremendous planning talent and military credentials, and the result was today's African Economic Union. The Reich held onto Kamerun, South Africa, and portions of the Congo, since regional leadership which could be trusted to follow Reich guidance proved impossible to locate.

Figure 100: The African Economic Union after the last independence grants, 1950

Thus, as the 1950s began, Germany's position was as benevolent leader of an economic sphere which dominated three continents and had research outposts on Antarctica, allies on South America, and no particular interest in North America or Australia. It could safely be described, in the Englishman Shakespeare's words, of bestriding the world like a colossus. However, there is evidence that even at this early date, the Fuehrer may have been thinking beyond that sphere.

* This is one of the few times where it is difficult for me to present Keppler's writing; Cronkite and Murrow belonged to the finest tradition of American journalism and their exposition of both German occupation and Stalin's cruelty took incredible courage given that they began drafting said work while still in Hitler's Germany. - W. Fredlund, trans.

Last edited:

An outstanding update, c0d5579.

By the way, in the previous update you had an picture of an carrier. Is that picture based on a real-life carrier?

By the way, in the previous update you had an picture of an carrier. Is that picture based on a real-life carrier?

Yes, it's CV-9, USS Essex, undergoing trials in 1942. Germany really has caught up in the carrier department, as you'll see in Part 2 (when I get to it...), wherein the Hermann Goering-class is deployed, featuring such wonders as supersonic aircraft before the Luftwaffe is routinely breaking the sound barrier and an angled runway. Matter of fact...

DRMS Hermann Goering with an exchange squadron from the Royal Navy on deck

DRMS Hermann Goering with an exchange squadron from the Royal Navy on deck

10,000 views - not bad for someone whose pace is either dry and academic, or breathless and overlooking every other significant event!

10,000 views - not bad for someone whose pace is either dry and academic, or breathless and overlooking every other significant event!

Or both?

Wow this is a great AAR!!! It is fascinating (and chilling) to read of your history-book accounts as if they were real history. Especially the parts where it explains how an unenlightened minority came to believe the American lies and this caused some "temporary" unrest

But I think you should change one name, namely that of the aircraft carrier... Ernst Thälmann was the last leader of the German communists (KPD) and died in a concentration camp. The Nazis would rather have named their aircraft carriers after Moses Goldberg than after him

But I think you should change one name, namely that of the aircraft carrier... Ernst Thälmann was the last leader of the German communists (KPD) and died in a concentration camp. The Nazis would rather have named their aircraft carriers after Moses Goldberg than after him

Figure 92: DRMS Ernst Thaelmann during Mediterranean trials, 1944

What are you talking about? There were no concentration camps in Germany, the extralegal measures of the 1930s were strictly temporary and had no place in a state ruled by laws. Ernst Thaelmann was a German patriot and a hero for his espionage activities against the great Red menace to the East!

(Though in this case, I'm running off units.csv, and happened to know that the Thaelmann was commissioned at about that time in about that place. YMMV - there are two DRMS Richtofens, one for Manfred and one for Wolfram, and I'm sure that gets very confusing for crewmembers.)

EDIT - Since Thaelmann was arrested in 1933, I'm going to retcon this one further. Thaelmann was part of a high-level prisoner exchange following the debacle of the Spanish Civil War in 1936; he died on Stalin's orders in 1943 in the Soviet war, and German propaganda insists to this day that he was a German first, a Communist second, and died as a martyr to German-ness.

(Though in this case, I'm running off units.csv, and happened to know that the Thaelmann was commissioned at about that time in about that place. YMMV - there are two DRMS Richtofens, one for Manfred and one for Wolfram, and I'm sure that gets very confusing for crewmembers.)

EDIT - Since Thaelmann was arrested in 1933, I'm going to retcon this one further. Thaelmann was part of a high-level prisoner exchange following the debacle of the Spanish Civil War in 1936; he died on Stalin's orders in 1943 in the Soviet war, and German propaganda insists to this day that he was a German first, a Communist second, and died as a martyr to German-ness.

I had planned on running this thing through 1955, but there's just so damn much text here already I decided to cut it off.

---

2. The Changing of the Guard

The salient feature of 1950s German society was the rise of a generation which had grown up under Party rule, in a Germany unfettered by the concerns of Versailles. Often, they displayed a reluctance to recognize the concerns of their elders. In many ways, it echoed the divide between the generation of Kaiser Wilhelm I and Kaiser Wilhelm II - those who could remember a Kingdom of Prussia and those who knew only an Empire of Germany; in this case, the elders remembered the dark period between the Wilhelmine and modern Reichs. Only among the Reich's uppermost levels of leadership was the inter-war period still a vivid memory, and even here, the names of the players changed in the 1950s.

First to leave the stage was Reichsmarschall Hermann Goering, who had in any case largely left public life by 1950 and handed the day-to-day operation of the Luftwaffe to his subordinates. Indeed, in the late 1940s, the Luftwaffe was largely managed by three men, the bomber marshals Albert Kesselring and Hugo Sperrle, and the Inspector of Fighters, General Adolf Galland. It came as a surprise to these three men when the Fuehrer promoted a relatively unknown man over all three of their heads - Robert Ritter von Greim, previously a relatively unknown fighter commander in the West who had seen some moderate action against the British. Von Greim, while a winner of the Knight's Cross for his performance, was hardly in the first rank of German aviation thought. It is the first instance of the Fuehrer's political instincts overriding the military situation so blatantly; the new Reichsmarschall was generally viewed as a political appointment only marginally better than the proposed promotion of former Lufthansa director General Eberhardt Milch.

Figure 101: Reichsmarschall Robert Ritter von Greim, commander of the Luftwaffe de facto from 1948, de jure from 1951

Against this backdrop, Hermann Goering withdrew into a sort of splendid isolation, living on his south German estate, Carinhall, and indulging in his passion for hunting and fine living. Goering had increasingly put on weight from the end of his active flight days, around 1942 or so, and by 1950 was grossly corpulent. Finding horses to fit his frame was a full-time job for his Luftwaffe adjutant, and the Reichsmarschall found himself in declining health as the 1950s began. It was difficult to suppress his spirit and zest for life, but increasingly his reliance on medically questionable treatments to keep him up and moving led to taking perhaps unnecessary health risks. On July 20, 1951, the long, eccentric career of Germany's first huntsman came to an end.

Figure 102: The official reason for General Goering's death was a fall from a horse; however, recent documents, such as this coroner's statement, make clear that substance abuse was the cause.

The Reichsmarschall's funeral was the most lavish in history, eclipsing even that of Field Marshal Hindenburg almost exactly 17 years prior. Every Geschwader of the Luftwaffe sent a representative flight to participate in the memorial parade, led wherever possible by pilots who had distinguished themselves in the War Years. Goering himself was buried at the foot of the new control-tower complex of Berlin's expanded airport, on the site of the prewar Tegel rocket research facility. Tegel-Goering Flughafen remains Berlin's main air traffic hub, and the Hermann-Goering-Luftmuseum, designed by Albert Speer in the immediate wake of the Reichsmarschall's death, remains a remarkable structure for the fact that it integrates a fully functioning control tower for the surrounding airport into a public-access space which includes every known surviving aircraft flown by the Reichsmarschall, and a wide selection of his memorabilia. The funeral eulogy was delivered by the Fuehrer himself - past the age of sixty and in clearly failing health, it would nevertheless be one of his most powerful peacetime speeches. It is worth quoting in part for the hints it gives to the Fuehrer's thinking during this period.

The Reichsmarine's response to their longtime rival's death was somewhat surprising. A new class of aircraft carrier had already been planned, and the first generation of German carriers was due for replacement. At the same time as the Reichsmarschall's death, the first generation of carrier-capable jet aircraft had been developed, culminating in the Messerschmitt P.1101 "Wanderfalke." The Wanderfalke was unique in its time for being able to vary its wing geometry in flight; this was in response to a Reichsmarine requirement that it maintain acceptable levels of structural rigidity for supersonic flight, while at the same time occupying minimal deck space.

Figure 103: The Me-1101 "Wanderfalke" was an object of intense study for the United States; here, a composite picture taken by the American aeronautics agency NACA shows its variable-geometry wing positions on an illegally-acquired specimen.

To the Wanderfalke's revolutionary new design was mated the concept of the steam catapult; this feature would be new on the ten new carriers which Reichsadmiral Raeder authorized following Goering's death. These ships would be known as the Hermann Goering-class; the Admiral could afford to be generous, since he had outlived his rival, and indeed would himself stay in uniform long enough to be present at all ten vessels' commissioning. Admiral Raeder was, by this point, beginning to feel his own age, though he was considerably better equipped to handle it than the Reichsmarschall had been. He had been in continuous service since 1894, and few admirals of any nation of any time had attained all that he had during that period. At this point, he could have chosen to retire at any time. He did not.

Instead, in addition to the Goering-class carriers and the Wanderfalke, the Reichsmarine entered into a doctrinal and technical renaissance. Two schools of thought emerged during this period, the so-called "Russian" and "Dutch" schools, with their names tied to the bases where their exponents were based. The Russian school held that carrier warfare was the future of modern naval thought and focused on big-ship, big-fleet operations, perfected over the early 1950s in the Baltic. The Dutch school held that the key to maintaining the Reich's supremacy was the oversight of the Reich's trade routes, and that the emphasis must be placed on trade protection and defense against so-called asymmetric threats, such as submarines or aircraft, which surface combatants had traditionally neglected. The fact that the Royal Air Force and the French Armee de l'Aire were available for inter-service training gave the Dutch school training exercises an additional realism which the highly secret Russian school operations in the Baltic perhaps lacked.

Technically, the Reichsmarine was at the top of its form during this period, developing new classes of all vessel weights - though, curiously, the submarine force was neglected for much of the early 1950s, perhaps because the Type XXI boats in service were already exceptional compared to the rest of the world's submarine forces. In 1952, the Reichsmarine test-launched its first ship-to-ship cruise missile, the Seeteufel. Though they were less than impressive, the Reichsmarine nevertheless ordered the laying down of a new class of battleships - the so-called "Marshals' Class," alternately referred to as die alte Pickelhaube (a kind of spiked helmet worn by the old-fashioned Prussian officer class - trans.) for their name-sources. The Hindenburg, Luddendorff, Schlieffen, and Bluecher were, admittedly, an intermediate step, but they were the first battleships anywhere whose primary armament was missile-based, though the missiles were launched from the same 450mm barrels that conventional shells would use.

Figure 103: DRMS Hindenburg during Baltic sea trials, 1953