Chapter III: Part XXXVI

Chapter III: The Lion’s Den

Part XXXVI

November 30, 1936

“Heil Hitler!” The SS Sturmbannführers raised bladed palms in the corridor.

Adolf Hitler and his entourage thundered through the Reichschancellery, returning the salutes of the guards and staff that lined the route to the conference room. It was late in the evening, but all the lights in the Bismarck-era building still burned brightly tonight. They entered the rear hallway now, and the entourage peeled off with final salutes.

The door at the back of the room was hurled open, and the Führer and his adjutant passed into the chamber, where his lieutenants stood to greet him -- von Küchler, Bayerlein, Canaris, Raeder and Göring.

“So,” the Warlord began as he sat down. “So. The Luftwaffe awaits. The Army awaits. The ships are slipping out of the harbors. As established at Saturday’s meeting, the weather forecasts of the last week have been Providential, and the invasion will proceed as planned without compelling reason otherwise. I expect I shall receive final reports here tonight, and then issue the final order personally.”

Cristoph Scholl’s stenotype fell silent, and Hitler paused.

“Hermann?”

General Göring cleared his throat and delivered his report. Over the last five nights, he said, Luftflotte II had carried out large-scale raids against London, hoping to draw up the last of ADGB’s fighter strength and destroy it. On the first night, November twenty-fifth, significant fighter strength had gone up as bombs fell on Hammersmith and Kensington. Unusually spirited combat had raged over the capital for two hours, as a second and third wave of Kesselring’s planes arrived from France. By dawn, word reached the Holy Mountain that German losses had been particularly high: 27 aircraft destroyed and another 21 that would not be serviceable for the next night’s raid. Yet the Luftwaffe had claimed 19 kills -- proportionally a far more devastating tally. On the night of the twenty-sixth, the RAF waited to intercept until the German bomber formations were on their way home, crossing over Kent. Dozens of Gauntlets dived from altitude, bypassing the Ju-52s and engaging their fighter escorts while they were low on fuel and unable to commit to a prolonged fight. That night, the Luftwaffe suffered even heavier losses -- 35 aircraft to the British 16. Yet by the third night, the British retired. ADGB had clearly realized that the Germans would be tolerant of heavy losses in order to inflict a knockout blow, and chose to keep its fighters grounded as German bombers pummeled targets in Piccadilly and the South Bank, as well was the RAF stations at Biggin Hill and Hornchurch. On the twenty-eighth and twenty-ninth, Kesselring hit everywhere, it seemed -- from the naval facilities at Sheerness to as far north as Colchester, but still Air Chief Marshal Steele avoided battle. In the early hours of the thirtieth, Kesselring cabled Göring in Berlin that ADGB was clearly determined to preserve the last of its strength. “Now nothing but the invasion,” Kesselring had written the Luftwaffe chief, “can draw them up in numbers.”

Lufwaffe Staff-HKK now estimated those numbers to be between 30 and 40 operational machines. In the north, some 400 other aircraft of all types were thought to be serviceable -- mainly bombers, scouts, transports and second-line aircraft, but as many as 190 of these were fighters held in other commands throughout Britain. These would surely be committed when the Air Staff was certain that a full-scale invasion was underway, although HKK estimated that full redeployment south could take several days.

Thus, Generalmajor Sperrle’s Luftflotte III, which had been used in a defensive role until the RAF ceased bombing missions over France in mid-November, was now focusing its efforts on keeping up as much pressure on the airfields as possible. Already, severe damage had been inflicted upon the fighter bases at Hawkinge, Duxford and Wittering, aided by the long stretch of clear weather which had hampered repairs. ADGB’s headquarters at Hillingdon House had been hit by several bombs, and intelligence reports indicated that operations staff had been removed to a fortified bunker at RAF Watford.

The skies above London were rent by fearsome air combat.

From now on, Kesselring’s planes would be devoted to direct support of the invasion -- providing fighter cover, bombing sorties and reconnaissance for ground forces, with one Geschwader, under Oberstleutnant Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen, dedicated to anti-ship operations in the Channel and up Britain’s eastern coastline. It would fall to this man, cousin of the famous Red Baron, to attempt to intercept the Home Fleet’s heavy units as they inevitably steamed toward the invasion area. Two Gruppen had been furnished with the new Ju-87 dive bomber, and one of these with the new armor-piercing bombs that General Wever had successfully lobbied for.

“If the Royal Oak and her sisters dare to sortie,” Göring concluded, “I promise you the Luftwaffe shall deliver their pennants to Berlin.”

Now Raeder, in his turn, was called to speak. Was the Kriegsmarine ready for the invasion?

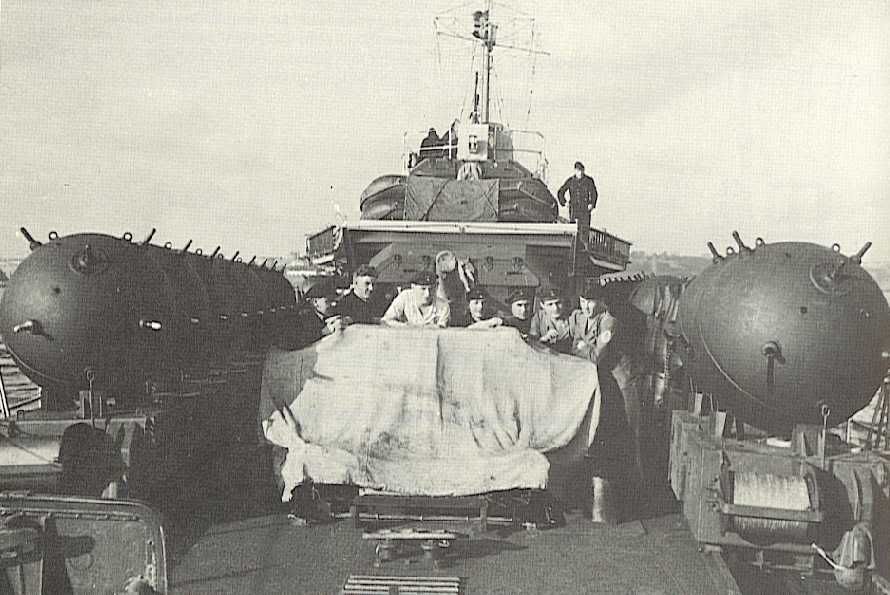

“For the Navy,” Raeder said, “the invasion has already begun.” In the early hours of the twenty-ninth, following yet another contentious Führerconference, Field Marshal von Küchler had signed into effect the orders authorizing the preliminary naval moves of the invasion. Minelayers had rushed out under cover of darkness to sow mines from Eastbourne to Dieppe. Thousands more mines would connect the thick minefields dotted between Great Yarmouth and the Hague into a single impenetrable cordon. Nine destroyers came out to play that night -- tussling eagerly with their German cousins, the larger Type 34s, and with the smaller torpedo boats that were their natural prey. One of the minelayers had gotten its screws shot off, and a handful of men on both sides had been killed by the wild gunfire, but it was an impenetrably dark night due to low cloud cover, and no more serious damage was reported. The minefields were coming along nicely, and crews reported that the British were sweeping them only slowly and with difficulty.

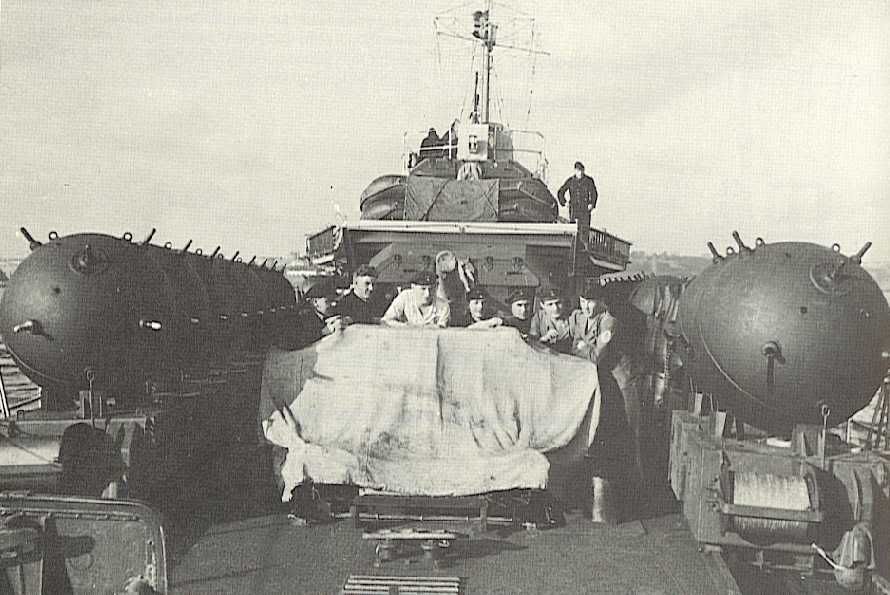

German minelayers sowed thousands of mines in an attempt to block the Home Fleet’s inevitable sally into the English Channel.

Minelayers ranged in size from small tugs and auxiliary craft (pictured) up to large converted merchant steamers such as the Kormoran, able to carry over 600 mines and make 20 knots.

The next night, a nearly full moon shone down on the Channel, and as the embarked invasion fleet began to assemble in formation in its harbors, battle was rejoined in deadly earnest. The "Messaging Nine" -- so named by their German counterparts for the gossipy flicker of signal lamps that seemed always to run between them -- sortied again, joined this time by a light cruiser from the north. In a furious battle that ranged up and down the English coast, the two sides tangled for hours in a murderous fusillade. The British destroyers managed to sink two of the smaller German minelayers, only to be seen off by the Karlsruhe and her 150 mm guns, whereupon the British cruiser tried to intervene and nearly ran aground trying to thread a minefield. By midnight, the Channel was bright as day between the flares, gunfire and antiaircraft searchlights turned on due to the German air raids. At last, Kapitän Siemens in the Karlsruhe was able to straddle the destroyer HMS Boadicea and batter her with several salvos of his heavy guns. Boadicea drifted, powerless and burning, into the path of her sister Brazen, which struck a mine trying to avoid her and retired to Portsmouth. Another German minelayer was soon sent to the bottom, followed by a British armed trawler caught in the crossfire.

By three, the German torpedo boats Luchs and Wolf were in a running battle off Hastings with the British cruiser, which was skillfully dodging their torpedos while returning fire. Yet so wild were the cruiser's maneuvers that her gunnery was next to useless. The two torpedo boats managed to get within a thousand meters, and as they fiercely jockeyed for the angle to launch their eels, the two sides exchanged withering fire with secondary armaments which soon glowed red hot. In the darkness, the ships looked as though they were spraying each other with solid streams of molten metal, and the water between them boiled with splashes. On the Wolf, the dead were stacked in heaps on the blood-slick deck, which was pitted and buckled by shellfire. Wolf's captain, Kapitänleutnant Wattenberg, was killed when a British shell passed through a bulkhead below the bridge and exploded, sending the bridge and everyone on it crashing down into the resulting inferno. The first officer tried to steer the ship from the station aft, but found this in the process of flooding from several hits below the waterline. With the ship's superstructure a twisted heap of sizzling metal, her funnels holed like colanders and reports now arriving of a magazine fire threatening the forward turret, he ordered his men to abandon ship.

This left Luchs facing the cruiser alone. The German ship managed to score a hit with one of her torpedos, but it was an apparent dud. The cruiser's prompt reply started a fire on her mine and torpedo deck, which quickly grew white hot as the Luchs' oxygen supply ruptured. The casualty-depleted firefighting crew couldn't hope to subdue the flames, which raged from compartment to compartment in minutes. Kapitänleutnant Kothe was informed that the aluminum in the after-magazine was beginning to melt, but he never had a chance to order Abandon Ship. Windows in Dymchurch rattled as an early dawn broke in the east -- Luchs exploded in an enormous, towering fireball that could be seen from as far away as Cap Gris-Nez.

Luchs’ mines and torpedos detonate spectacularly at 0351 on November 30. The explosion caused alarm along the English coast.

Numerous such duels played out across the Channel in the ensuing hours. The cruiser managed to sink another German -- the large minelayer Schwan -- in the shallows off Dungeness but in the process ran aground herself. The vengeful sisters of the Luchs and Wolf closed in twice to attempt a coup de grâce, but although beached, the cruiser was still operational, and kept them at a distance with 6 inch gunfire. As the sky was beginning to lighten, Kapitän Siemens brought the Karlsruhe and two destroyers north to intercept Dover's destroyer squadron as it returned to port. German gunnery had sunk one of the British destroyers outright, while another had had its back broken by a U-boat that had arrived to cut off its retreat. Yet the lone survivor, HMS Firedrake, had charged straight for the far superior German cruiser with guns blazing and knocked two of her three turrets out of action, forcing her to slip back to Amsterdam for repairs.

The Channel Battles of November 28-29 were energetically fought on both sides, but were tactically indecisive -- Royal Navy ships could still sortie into the Channel at night.

“Karlsruhe cannot assist the landings at all, then?” Hitler asked. “Even the second wave?”

Raeder’s face was drawn. “We cannot say with certainty, Mein Führer. We are having replacement barrels and barbette machinery shipped specially by rail from Wilhelmshaven. Perhaps she can fight in a week. In an emergency, she could put to sea with repairs incomplete.”

“What sort of emergency do you envision?”

“If, for example, the Royal Navy is able to concentrate its forces more quickly that we have anticipated.”

“But remember,” Admiral Canaris said quickly, “our estimates are carefully measured, and even at the earliest, the Home Fleet could not arrive before our second wave. Rather, Mein Führer, it is the destroyer battles in the Channel that are of most import to the outcome of Löwengrube.”

Canaris' analysts placed eleven British destroyers near enough to reach the invasion areas within several hours: one at Sheerness, two at Dover, three at Harwich, and five at Portsmouth. Within a full day's steaming, there were two light cruisers on the Humber and one on the Tyne, with another three destroyers at Rosyth. Within forty-eight hours, the full weight of the Home Fleet's capital ships could reach the Channel: three destroyers, five light cruisers, three battleships -- Ramillies, Resolution and Royal Oak -- and the puny old aircraft carrier HMS Hermes, used in place of the nearly-repaired Eagle. Within five days of the invasion, another thirty destroyers and four light cruisers could come in from the Atlantic patrol in an attempt to close the Straits. After that -- from a week to one month after the start of Löwengrube, virtually anything could reasonably be expected to be found in home waters.

But as for the Home Fleet, even forty-eight hours was uncomfortably soon, so Raeder had at last consented to a diversionary sortie by the Kriegsmarine’s heavy units. The pocket battleships Deutschland, Admiral Scheer and Admiral Graf Spee, along with several of the light cruisers, had set sail from Wilhelmshaven under Konteradmiral Wilhelm Marschall in the early hours of the twenty-ninth, bound for the Viking Bank off Norway. Radio silence had been intentionally breached, and German cryptanalysis had confirmed that the Royal Navy was aware of the move. There was as yet no indication whether they would “take the bait.” But Raeder was counting on the pocket battleships’ speed and firepower to protect them in what might otherwise have been a suicidal mission. The Panzerschiffe were far faster than the British battleships, and solidly outgunned the cruisers fast enough to catch them.

Konteradmiral Marschall, until recently captain of the Admiral Scheer, had been a celebrated U-boat ace from the last war, decorated with the pour le mérite, and now found himself under familiar orders. The German capital ships were to stay concentrated, engaging inferior forces, or any units of the Home Fleet that could be isolated and picked off safely. In the face of dreadnoughts, they were to fade back into the vast northern seas, leading their adversaries on a merry chase. In no event, Raeder had ordered Marschall, were the Panzerschiffe to be wasted in pitched battle with an evenly-matched enemy. Even now, the cream of the Germany Navy was steaming through the North Sea, carrying the hopes of its Commander-in-Chief that its gamble could win precious days or hours at the beachhead.

Yet regardless of the outcome of Marschall’s sortie, the enemy destroyers already in the Channel had to be neutralized by whatever means possible. To that end, massive bombing was scheduled for the naval facilities at Portsmouth, aimed at hamstringing the still-powerful squadrons there. Meanwhile, Königsberg and two Type 34 destroyers would sortie to Harwich, trying to lure the destroyers there into a U-boat ambush, or, failing that, sink them on their own. These ships would pose the greatest threat to the immediate survival of the invasion, and accordingly received priority. Canaris conceded that the destroyer at Sheerness, as well as any number of the smaller corvettes, sloops and trawlers that would be sure to menace the German transports, would simply have to be dealt with ad hoc, on the day.

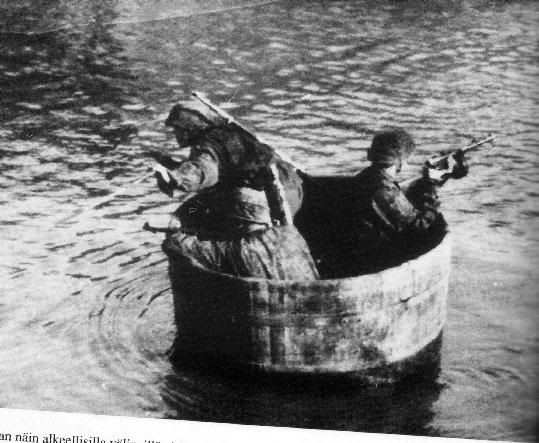

Räumboote set out from Calais on the night of November 30 to screen the invasion force.

The transports, now mostly embarked and awaiting orders to sail, were in fact most worried about submarines. Just the night before, a British submarine had torpedoed and sunk the transport Königstein off Ostend with great loss of life, and men embarked on other ships were frequently exhorted to wear their life jackets at all times until they set foot in England. Those lucky enough to be crossing in the destroyers would be sprinted across the Channel in as little as twenty minutes. Those in the transports -- the fast liners, troopships and converted passenger steamers -- would take between forty-five minutes and five hours, depending on route and vessel. Yet thousands of men and thousands of tons of matériel would still be forced to make the crossing in the slower, smaller vessels, ranging from picket boats and armed tugs to ammunition lighters, riverboats and towed Rhine barges. The latter categories, due to their vulnerability, would only be expected to make the crossing once. With the first wave ashore, they were to remain in the landing areas and assist in the unloading of the second wave.

Lighters and barges had been diverted from industrial and commercial shipping to the effort to ship as much war matériel across the Channel in the first wave as possible.

Part of the invasion fleet gathers off Holland.

Vessels for the invasion assume formation in the Scheldt estuary.

“The timetable remains unchanged?” Hitler asked.

“That is correct,” von Küchler said. “The first wave shall cross in the twelve hours after the order to sail is given. The second wave should be across by the start of day three. Over the next two weeks, additional equipment, guns and supplies will make the crossing whenever the Channel is clear in order to bring units up to full strength.”

“So twelve divisions, by that point...”

“Yes.”

“For us,” Bayerlein clarified. “There are about five enemy divisions in England.”

Canaris looked over his notes. “The great preponderance of the British Empire's strength is still in Africa and the Mediterranean. It has approximately eleven divisions in Egypt and Palestine, as well as several brigades of besieged forces at Alexandria. In addition, there are six divisions still fighting hard in Tunisia, as well as French units -- dispirited French units -- there, which amount to the equivalent of perhaps one more. We estimate some seventeen British divisions in East Africa. The British Army's strength in the Home Islands has been growing rapidly in recent weeks, mainly at the expense of troops in Palestine. We can count on the invasion being opposed by four good regular divisions, plus one of colonials -- evidently from India -- and one brigade of tanks. Additionally, there are probably three or four divisions staging in Liverpool and Wales for transfer to Ireland. We do not have much corroborating evidence yet, but from the nature of the buildup it appears that they intend to effect a crossing within the next six weeks.”

Hitler frowned. “Troops diverted from the Mediterranean?”

“Yes,” the Spymaster said. “About three or four divisions so far.”

“You said Bastico would keep them tied down, Admiral.”

“He keeps most of them tied down, Mein Führer, but the Italians are not as strong as they were over the summer. While they’re pushing for the Suez again in Egypt, their Badoglio -- who was once trying to capture Karthoum -- is now fighting just to avoid encirclement and destruction.”

A shadow passed over the Führer’s face, and he quickly changed the subject. “Weather. The weather. The weather. The weather is still good, Admiral?”

“As far as we can tell, acceptable or better weather for the next two weeks. Snow squalls here and there, of course, but our planes should never be grounded for more than half a day.”

“So, very well. So, Very well, then.”

To Scholl it appeared as if the Führer was casting frantically about for some excuse to delay the final moment, but in recent weeks, Canaris had addressed every concern inside and out. To delay further could doom the whole invasion.

“Very well. I shall deliver the radio address tomorrow evening, once it is already underway. Baron von Neurath is to deflect any diplomatic attention until that time.”

Scholl noted that a memorandum to the Foreign Minister would have to be drafted.

“Good Bayerlein, if you could recapitulate the general Löwengrube landing plans for us one more time?”

The former Oberstleutnant exchanged glances with Canaris. The Admiral nodded slightly.

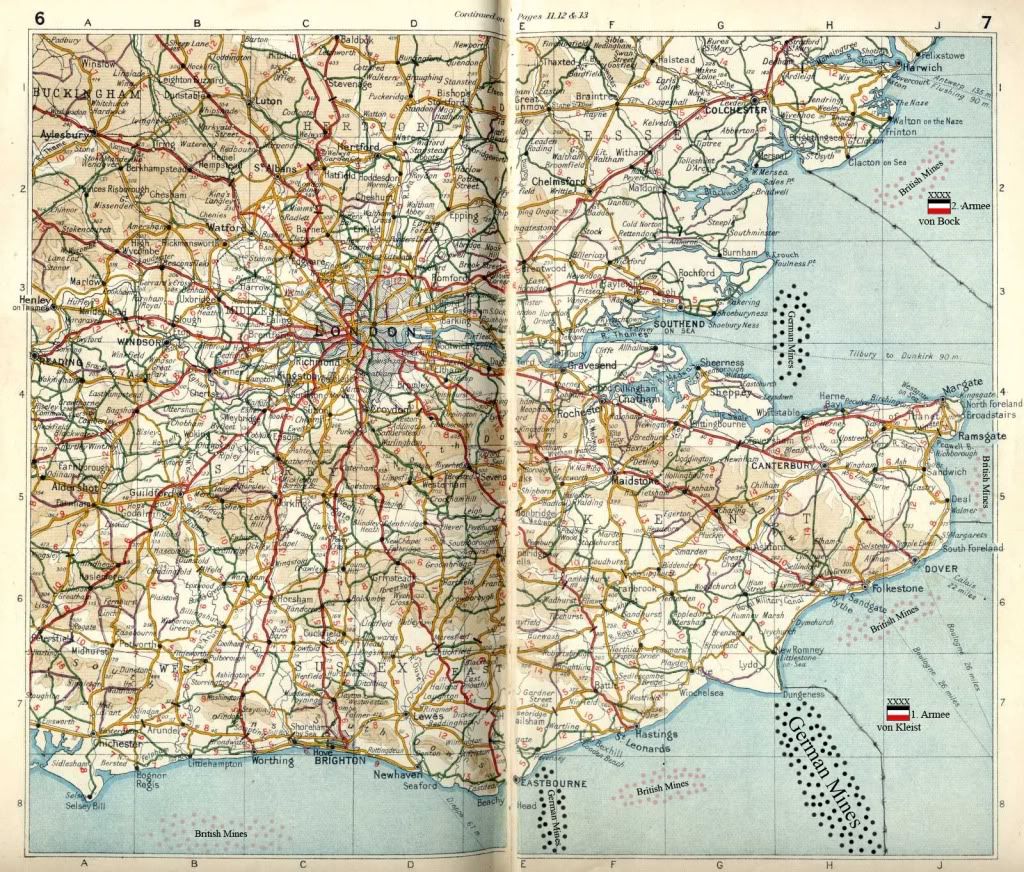

Bayerlein stood, and moved to a large easel which two aides had set up, and unrolled upon it a large map of the invasion areas. For forty-five minutes, he talked the Führer through the final plan for Löwengrube.

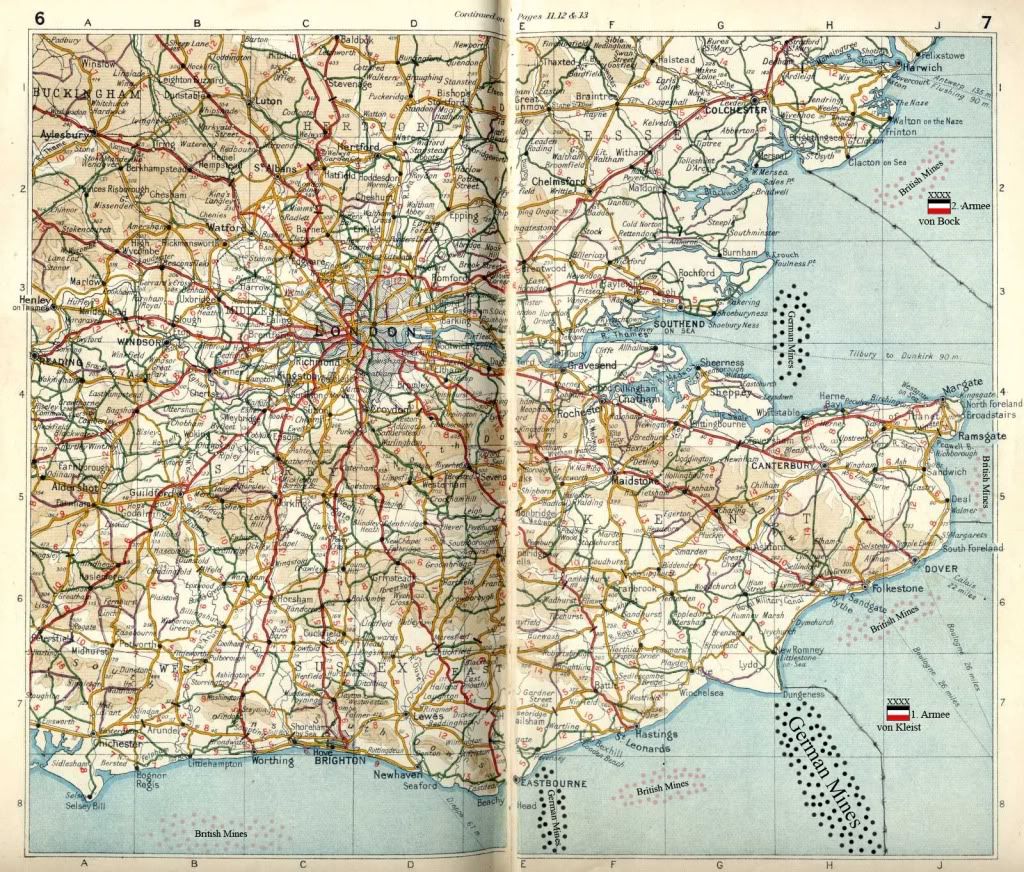

General map of invasion area.

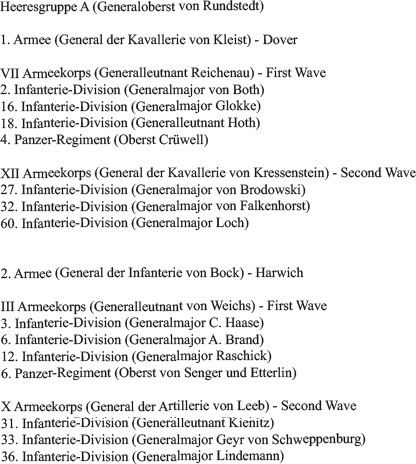

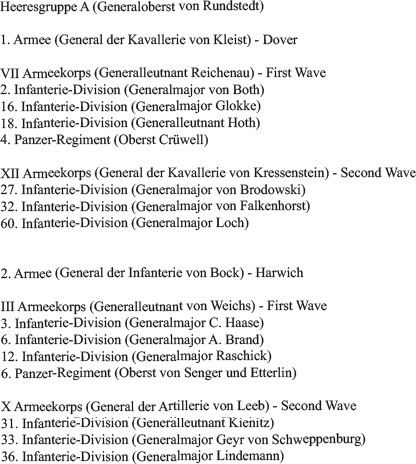

German Order of Battle, Unternehmen Löwengrube landings.

Heeresgruppe A, under Generaloberst von Rundstedt, was comprised of three nominal armies, the first two of which would participate in the actual invasion. 1. Armee, under General der Kavallerie von Kleist, would land at and around Dover. The first wave, Generalleutnant von Reichenau's VII Armeekorps, would promptly move to capture the port of Folkestone and then northwest to Ashford to secure 1. Armee's left flank before driving headlong toward London by way of Maidstone. The second wave, XII Armeekorps, under the Bavarian nobleman General der Kavallerie Franz Freiherr Kress von Kressenstein, was charged with taking Canterbury and preventing counterattack by the large forces around Ramsgate. Meanwhile, 2. Armee, commanded by General der Infanterie von Bock, would land at Harwich and Felixstowe, and was charged with threatening London from the rear. Its first wave, Generalleutnant von Weichs' III Armeekorps, would take Ipswich, and then join with General der Artillerie von Leeb's X Armeekorps in a forceful push through Essex and into London's northern approaches. In so doing, HKK hoped, they would prevent the British from sending reinforcements to Kent, and allow von Kleist to establish himself immovably on the road to London before having to meet the bulk of the enemy's strength.

All this would depend, of course, upon whether the critical deep-water ports of Dover and Harwich could be captured quickly and intact. The Abwehr had no idea whether the docks were wired for demolition, but had to proceed under the assumption that they were. As such, the move to seize them would have to be the very opening gambit of the whole invasion. HKK had no illusions of Löwengrube's prospects if it failed, and would hold the invasion fleets at their staging points near the French coast until word came that the ports were secure. If all went well, that word would come within as little as six hours now. "You have reserved to yourself the authority to give the final order for the first blow, Mein Führer," Bayerlein said at last, returning to his seat. "That time has now come."

The Warlord, skin pale but face set, nodded solemnly. He picked up the telephone to von Rundstedt's headquarters in Calais, and in a sentence cast Germany's dice onto the table.

Chapter III: The Lion’s Den

Part XXXVI

November 30, 1936

“Heil Hitler!” The SS Sturmbannführers raised bladed palms in the corridor.

Adolf Hitler and his entourage thundered through the Reichschancellery, returning the salutes of the guards and staff that lined the route to the conference room. It was late in the evening, but all the lights in the Bismarck-era building still burned brightly tonight. They entered the rear hallway now, and the entourage peeled off with final salutes.

The door at the back of the room was hurled open, and the Führer and his adjutant passed into the chamber, where his lieutenants stood to greet him -- von Küchler, Bayerlein, Canaris, Raeder and Göring.

“So,” the Warlord began as he sat down. “So. The Luftwaffe awaits. The Army awaits. The ships are slipping out of the harbors. As established at Saturday’s meeting, the weather forecasts of the last week have been Providential, and the invasion will proceed as planned without compelling reason otherwise. I expect I shall receive final reports here tonight, and then issue the final order personally.”

Cristoph Scholl’s stenotype fell silent, and Hitler paused.

“Hermann?”

General Göring cleared his throat and delivered his report. Over the last five nights, he said, Luftflotte II had carried out large-scale raids against London, hoping to draw up the last of ADGB’s fighter strength and destroy it. On the first night, November twenty-fifth, significant fighter strength had gone up as bombs fell on Hammersmith and Kensington. Unusually spirited combat had raged over the capital for two hours, as a second and third wave of Kesselring’s planes arrived from France. By dawn, word reached the Holy Mountain that German losses had been particularly high: 27 aircraft destroyed and another 21 that would not be serviceable for the next night’s raid. Yet the Luftwaffe had claimed 19 kills -- proportionally a far more devastating tally. On the night of the twenty-sixth, the RAF waited to intercept until the German bomber formations were on their way home, crossing over Kent. Dozens of Gauntlets dived from altitude, bypassing the Ju-52s and engaging their fighter escorts while they were low on fuel and unable to commit to a prolonged fight. That night, the Luftwaffe suffered even heavier losses -- 35 aircraft to the British 16. Yet by the third night, the British retired. ADGB had clearly realized that the Germans would be tolerant of heavy losses in order to inflict a knockout blow, and chose to keep its fighters grounded as German bombers pummeled targets in Piccadilly and the South Bank, as well was the RAF stations at Biggin Hill and Hornchurch. On the twenty-eighth and twenty-ninth, Kesselring hit everywhere, it seemed -- from the naval facilities at Sheerness to as far north as Colchester, but still Air Chief Marshal Steele avoided battle. In the early hours of the thirtieth, Kesselring cabled Göring in Berlin that ADGB was clearly determined to preserve the last of its strength. “Now nothing but the invasion,” Kesselring had written the Luftwaffe chief, “can draw them up in numbers.”

Lufwaffe Staff-HKK now estimated those numbers to be between 30 and 40 operational machines. In the north, some 400 other aircraft of all types were thought to be serviceable -- mainly bombers, scouts, transports and second-line aircraft, but as many as 190 of these were fighters held in other commands throughout Britain. These would surely be committed when the Air Staff was certain that a full-scale invasion was underway, although HKK estimated that full redeployment south could take several days.

Thus, Generalmajor Sperrle’s Luftflotte III, which had been used in a defensive role until the RAF ceased bombing missions over France in mid-November, was now focusing its efforts on keeping up as much pressure on the airfields as possible. Already, severe damage had been inflicted upon the fighter bases at Hawkinge, Duxford and Wittering, aided by the long stretch of clear weather which had hampered repairs. ADGB’s headquarters at Hillingdon House had been hit by several bombs, and intelligence reports indicated that operations staff had been removed to a fortified bunker at RAF Watford.

The skies above London were rent by fearsome air combat.

From now on, Kesselring’s planes would be devoted to direct support of the invasion -- providing fighter cover, bombing sorties and reconnaissance for ground forces, with one Geschwader, under Oberstleutnant Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen, dedicated to anti-ship operations in the Channel and up Britain’s eastern coastline. It would fall to this man, cousin of the famous Red Baron, to attempt to intercept the Home Fleet’s heavy units as they inevitably steamed toward the invasion area. Two Gruppen had been furnished with the new Ju-87 dive bomber, and one of these with the new armor-piercing bombs that General Wever had successfully lobbied for.

“If the Royal Oak and her sisters dare to sortie,” Göring concluded, “I promise you the Luftwaffe shall deliver their pennants to Berlin.”

Now Raeder, in his turn, was called to speak. Was the Kriegsmarine ready for the invasion?

“For the Navy,” Raeder said, “the invasion has already begun.” In the early hours of the twenty-ninth, following yet another contentious Führerconference, Field Marshal von Küchler had signed into effect the orders authorizing the preliminary naval moves of the invasion. Minelayers had rushed out under cover of darkness to sow mines from Eastbourne to Dieppe. Thousands more mines would connect the thick minefields dotted between Great Yarmouth and the Hague into a single impenetrable cordon. Nine destroyers came out to play that night -- tussling eagerly with their German cousins, the larger Type 34s, and with the smaller torpedo boats that were their natural prey. One of the minelayers had gotten its screws shot off, and a handful of men on both sides had been killed by the wild gunfire, but it was an impenetrably dark night due to low cloud cover, and no more serious damage was reported. The minefields were coming along nicely, and crews reported that the British were sweeping them only slowly and with difficulty.

German minelayers sowed thousands of mines in an attempt to block the Home Fleet’s inevitable sally into the English Channel.

Minelayers ranged in size from small tugs and auxiliary craft (pictured) up to large converted merchant steamers such as the Kormoran, able to carry over 600 mines and make 20 knots.

The next night, a nearly full moon shone down on the Channel, and as the embarked invasion fleet began to assemble in formation in its harbors, battle was rejoined in deadly earnest. The "Messaging Nine" -- so named by their German counterparts for the gossipy flicker of signal lamps that seemed always to run between them -- sortied again, joined this time by a light cruiser from the north. In a furious battle that ranged up and down the English coast, the two sides tangled for hours in a murderous fusillade. The British destroyers managed to sink two of the smaller German minelayers, only to be seen off by the Karlsruhe and her 150 mm guns, whereupon the British cruiser tried to intervene and nearly ran aground trying to thread a minefield. By midnight, the Channel was bright as day between the flares, gunfire and antiaircraft searchlights turned on due to the German air raids. At last, Kapitän Siemens in the Karlsruhe was able to straddle the destroyer HMS Boadicea and batter her with several salvos of his heavy guns. Boadicea drifted, powerless and burning, into the path of her sister Brazen, which struck a mine trying to avoid her and retired to Portsmouth. Another German minelayer was soon sent to the bottom, followed by a British armed trawler caught in the crossfire.

By three, the German torpedo boats Luchs and Wolf were in a running battle off Hastings with the British cruiser, which was skillfully dodging their torpedos while returning fire. Yet so wild were the cruiser's maneuvers that her gunnery was next to useless. The two torpedo boats managed to get within a thousand meters, and as they fiercely jockeyed for the angle to launch their eels, the two sides exchanged withering fire with secondary armaments which soon glowed red hot. In the darkness, the ships looked as though they were spraying each other with solid streams of molten metal, and the water between them boiled with splashes. On the Wolf, the dead were stacked in heaps on the blood-slick deck, which was pitted and buckled by shellfire. Wolf's captain, Kapitänleutnant Wattenberg, was killed when a British shell passed through a bulkhead below the bridge and exploded, sending the bridge and everyone on it crashing down into the resulting inferno. The first officer tried to steer the ship from the station aft, but found this in the process of flooding from several hits below the waterline. With the ship's superstructure a twisted heap of sizzling metal, her funnels holed like colanders and reports now arriving of a magazine fire threatening the forward turret, he ordered his men to abandon ship.

This left Luchs facing the cruiser alone. The German ship managed to score a hit with one of her torpedos, but it was an apparent dud. The cruiser's prompt reply started a fire on her mine and torpedo deck, which quickly grew white hot as the Luchs' oxygen supply ruptured. The casualty-depleted firefighting crew couldn't hope to subdue the flames, which raged from compartment to compartment in minutes. Kapitänleutnant Kothe was informed that the aluminum in the after-magazine was beginning to melt, but he never had a chance to order Abandon Ship. Windows in Dymchurch rattled as an early dawn broke in the east -- Luchs exploded in an enormous, towering fireball that could be seen from as far away as Cap Gris-Nez.

Luchs’ mines and torpedos detonate spectacularly at 0351 on November 30. The explosion caused alarm along the English coast.

Numerous such duels played out across the Channel in the ensuing hours. The cruiser managed to sink another German -- the large minelayer Schwan -- in the shallows off Dungeness but in the process ran aground herself. The vengeful sisters of the Luchs and Wolf closed in twice to attempt a coup de grâce, but although beached, the cruiser was still operational, and kept them at a distance with 6 inch gunfire. As the sky was beginning to lighten, Kapitän Siemens brought the Karlsruhe and two destroyers north to intercept Dover's destroyer squadron as it returned to port. German gunnery had sunk one of the British destroyers outright, while another had had its back broken by a U-boat that had arrived to cut off its retreat. Yet the lone survivor, HMS Firedrake, had charged straight for the far superior German cruiser with guns blazing and knocked two of her three turrets out of action, forcing her to slip back to Amsterdam for repairs.

The Channel Battles of November 28-29 were energetically fought on both sides, but were tactically indecisive -- Royal Navy ships could still sortie into the Channel at night.

“Karlsruhe cannot assist the landings at all, then?” Hitler asked. “Even the second wave?”

Raeder’s face was drawn. “We cannot say with certainty, Mein Führer. We are having replacement barrels and barbette machinery shipped specially by rail from Wilhelmshaven. Perhaps she can fight in a week. In an emergency, she could put to sea with repairs incomplete.”

“What sort of emergency do you envision?”

“If, for example, the Royal Navy is able to concentrate its forces more quickly that we have anticipated.”

“But remember,” Admiral Canaris said quickly, “our estimates are carefully measured, and even at the earliest, the Home Fleet could not arrive before our second wave. Rather, Mein Führer, it is the destroyer battles in the Channel that are of most import to the outcome of Löwengrube.”

Canaris' analysts placed eleven British destroyers near enough to reach the invasion areas within several hours: one at Sheerness, two at Dover, three at Harwich, and five at Portsmouth. Within a full day's steaming, there were two light cruisers on the Humber and one on the Tyne, with another three destroyers at Rosyth. Within forty-eight hours, the full weight of the Home Fleet's capital ships could reach the Channel: three destroyers, five light cruisers, three battleships -- Ramillies, Resolution and Royal Oak -- and the puny old aircraft carrier HMS Hermes, used in place of the nearly-repaired Eagle. Within five days of the invasion, another thirty destroyers and four light cruisers could come in from the Atlantic patrol in an attempt to close the Straits. After that -- from a week to one month after the start of Löwengrube, virtually anything could reasonably be expected to be found in home waters.

But as for the Home Fleet, even forty-eight hours was uncomfortably soon, so Raeder had at last consented to a diversionary sortie by the Kriegsmarine’s heavy units. The pocket battleships Deutschland, Admiral Scheer and Admiral Graf Spee, along with several of the light cruisers, had set sail from Wilhelmshaven under Konteradmiral Wilhelm Marschall in the early hours of the twenty-ninth, bound for the Viking Bank off Norway. Radio silence had been intentionally breached, and German cryptanalysis had confirmed that the Royal Navy was aware of the move. There was as yet no indication whether they would “take the bait.” But Raeder was counting on the pocket battleships’ speed and firepower to protect them in what might otherwise have been a suicidal mission. The Panzerschiffe were far faster than the British battleships, and solidly outgunned the cruisers fast enough to catch them.

Konteradmiral Marschall, until recently captain of the Admiral Scheer, had been a celebrated U-boat ace from the last war, decorated with the pour le mérite, and now found himself under familiar orders. The German capital ships were to stay concentrated, engaging inferior forces, or any units of the Home Fleet that could be isolated and picked off safely. In the face of dreadnoughts, they were to fade back into the vast northern seas, leading their adversaries on a merry chase. In no event, Raeder had ordered Marschall, were the Panzerschiffe to be wasted in pitched battle with an evenly-matched enemy. Even now, the cream of the Germany Navy was steaming through the North Sea, carrying the hopes of its Commander-in-Chief that its gamble could win precious days or hours at the beachhead.

Yet regardless of the outcome of Marschall’s sortie, the enemy destroyers already in the Channel had to be neutralized by whatever means possible. To that end, massive bombing was scheduled for the naval facilities at Portsmouth, aimed at hamstringing the still-powerful squadrons there. Meanwhile, Königsberg and two Type 34 destroyers would sortie to Harwich, trying to lure the destroyers there into a U-boat ambush, or, failing that, sink them on their own. These ships would pose the greatest threat to the immediate survival of the invasion, and accordingly received priority. Canaris conceded that the destroyer at Sheerness, as well as any number of the smaller corvettes, sloops and trawlers that would be sure to menace the German transports, would simply have to be dealt with ad hoc, on the day.

Räumboote set out from Calais on the night of November 30 to screen the invasion force.

The transports, now mostly embarked and awaiting orders to sail, were in fact most worried about submarines. Just the night before, a British submarine had torpedoed and sunk the transport Königstein off Ostend with great loss of life, and men embarked on other ships were frequently exhorted to wear their life jackets at all times until they set foot in England. Those lucky enough to be crossing in the destroyers would be sprinted across the Channel in as little as twenty minutes. Those in the transports -- the fast liners, troopships and converted passenger steamers -- would take between forty-five minutes and five hours, depending on route and vessel. Yet thousands of men and thousands of tons of matériel would still be forced to make the crossing in the slower, smaller vessels, ranging from picket boats and armed tugs to ammunition lighters, riverboats and towed Rhine barges. The latter categories, due to their vulnerability, would only be expected to make the crossing once. With the first wave ashore, they were to remain in the landing areas and assist in the unloading of the second wave.

Lighters and barges had been diverted from industrial and commercial shipping to the effort to ship as much war matériel across the Channel in the first wave as possible.

Part of the invasion fleet gathers off Holland.

Vessels for the invasion assume formation in the Scheldt estuary.

“The timetable remains unchanged?” Hitler asked.

“That is correct,” von Küchler said. “The first wave shall cross in the twelve hours after the order to sail is given. The second wave should be across by the start of day three. Over the next two weeks, additional equipment, guns and supplies will make the crossing whenever the Channel is clear in order to bring units up to full strength.”

“So twelve divisions, by that point...”

“Yes.”

“For us,” Bayerlein clarified. “There are about five enemy divisions in England.”

Canaris looked over his notes. “The great preponderance of the British Empire's strength is still in Africa and the Mediterranean. It has approximately eleven divisions in Egypt and Palestine, as well as several brigades of besieged forces at Alexandria. In addition, there are six divisions still fighting hard in Tunisia, as well as French units -- dispirited French units -- there, which amount to the equivalent of perhaps one more. We estimate some seventeen British divisions in East Africa. The British Army's strength in the Home Islands has been growing rapidly in recent weeks, mainly at the expense of troops in Palestine. We can count on the invasion being opposed by four good regular divisions, plus one of colonials -- evidently from India -- and one brigade of tanks. Additionally, there are probably three or four divisions staging in Liverpool and Wales for transfer to Ireland. We do not have much corroborating evidence yet, but from the nature of the buildup it appears that they intend to effect a crossing within the next six weeks.”

Hitler frowned. “Troops diverted from the Mediterranean?”

“Yes,” the Spymaster said. “About three or four divisions so far.”

“You said Bastico would keep them tied down, Admiral.”

“He keeps most of them tied down, Mein Führer, but the Italians are not as strong as they were over the summer. While they’re pushing for the Suez again in Egypt, their Badoglio -- who was once trying to capture Karthoum -- is now fighting just to avoid encirclement and destruction.”

A shadow passed over the Führer’s face, and he quickly changed the subject. “Weather. The weather. The weather. The weather is still good, Admiral?”

“As far as we can tell, acceptable or better weather for the next two weeks. Snow squalls here and there, of course, but our planes should never be grounded for more than half a day.”

“So, very well. So, Very well, then.”

To Scholl it appeared as if the Führer was casting frantically about for some excuse to delay the final moment, but in recent weeks, Canaris had addressed every concern inside and out. To delay further could doom the whole invasion.

“Very well. I shall deliver the radio address tomorrow evening, once it is already underway. Baron von Neurath is to deflect any diplomatic attention until that time.”

Scholl noted that a memorandum to the Foreign Minister would have to be drafted.

“Good Bayerlein, if you could recapitulate the general Löwengrube landing plans for us one more time?”

The former Oberstleutnant exchanged glances with Canaris. The Admiral nodded slightly.

Bayerlein stood, and moved to a large easel which two aides had set up, and unrolled upon it a large map of the invasion areas. For forty-five minutes, he talked the Führer through the final plan for Löwengrube.

General map of invasion area.

German Order of Battle, Unternehmen Löwengrube landings.

Heeresgruppe A, under Generaloberst von Rundstedt, was comprised of three nominal armies, the first two of which would participate in the actual invasion. 1. Armee, under General der Kavallerie von Kleist, would land at and around Dover. The first wave, Generalleutnant von Reichenau's VII Armeekorps, would promptly move to capture the port of Folkestone and then northwest to Ashford to secure 1. Armee's left flank before driving headlong toward London by way of Maidstone. The second wave, XII Armeekorps, under the Bavarian nobleman General der Kavallerie Franz Freiherr Kress von Kressenstein, was charged with taking Canterbury and preventing counterattack by the large forces around Ramsgate. Meanwhile, 2. Armee, commanded by General der Infanterie von Bock, would land at Harwich and Felixstowe, and was charged with threatening London from the rear. Its first wave, Generalleutnant von Weichs' III Armeekorps, would take Ipswich, and then join with General der Artillerie von Leeb's X Armeekorps in a forceful push through Essex and into London's northern approaches. In so doing, HKK hoped, they would prevent the British from sending reinforcements to Kent, and allow von Kleist to establish himself immovably on the road to London before having to meet the bulk of the enemy's strength.

All this would depend, of course, upon whether the critical deep-water ports of Dover and Harwich could be captured quickly and intact. The Abwehr had no idea whether the docks were wired for demolition, but had to proceed under the assumption that they were. As such, the move to seize them would have to be the very opening gambit of the whole invasion. HKK had no illusions of Löwengrube's prospects if it failed, and would hold the invasion fleets at their staging points near the French coast until word came that the ports were secure. If all went well, that word would come within as little as six hours now. "You have reserved to yourself the authority to give the final order for the first blow, Mein Führer," Bayerlein said at last, returning to his seat. "That time has now come."

The Warlord, skin pale but face set, nodded solemnly. He picked up the telephone to von Rundstedt's headquarters in Calais, and in a sentence cast Germany's dice onto the table.

Last edited: