18.2. THE REIGN OF DECIUS. THE CHANGING SITUATION IN THE EMPIRE’S NORTHERN BORDERS.

Traditionally, the danger posed by the “barbarian hordes” that could invade Italy across the Alps had been the Romans’ national nightmare, ever since Brennus’ Gauls sacked Rome in the IV century BCE. The last great scare had been the invasion by the Cimbri and Teutones in the late II century BCE. After that, the Roman conquest of Gaul and the Danubian provinces under Caesar and Augustus had brought a degree of security to Italy, and the northern “barbarians” had become either an object of contemptuous disdain, to be contained through diplomacy and punitive expeditions, or to be used by nostalgic traditionalists as examples of the “original virtues” that the Romans had supposedly lost.

From the first century onwards, many northern “barbarians” served in the Roman army, and the proportion of such people probably increased as the provincialization of the imperial interior made army service less and less attractive to Roman civilians. The benefits of service in the army to a foreigner from beyond the northern borders were substantial: not only did service in an auxiliary (non-citizen) unit pay well, it brought with it Roman citizenship after honorable discharge and often a substantial discharge bonus. Many of these foreigners who served in the army became entirely used to a Roman way of life, living out their lives inside the empire and dying there as Roman citizens after long years of service. Others, however, returned to their native communities beyond the frontier, bringing with them Roman habits and tastes, along with Roman money and products of different sorts. Their presence contributed to the demand for more Roman products beyond the frontiers, which helped increase trade between the empire and its neighbors.

After Augustus’s time, even in periods of peace, Roman military power was always present as a threat for the empire’s neighbors. Military victories were a vital legitimizing device for imperial power and very few emperors were secure enough on their thrones to pass up the occasional aggressive war. The need for imperial victories translated into periodic assaults upon the empire’s neighbors, the imposition of tribute, the taking of hostages, the collection of slaves, the pillaging of villages by Roman soldiers. Roman military aggression was by no means relentless, but it was never beyond the realm of possibility. Every generation born along the imperial frontier at some point experienced the attentions of the Roman military. The empire and its army were thus in and of themselves an ongoing spur to social change in the barbarian societies that bordered the imperial frontiers: their leaders had every incentive to make themselves more potent militarily. To the Romans, their northern neighbors were little more than punching bags to exercise their military muscle whenever they felt like it.

The Column of Marcus Aurelius in Rome celebrates the victories of this emperor in the Marcomannic Wars. Unlike the Trajan Columns, in this case the Roman sculptors did not avoid showing the dark side of Roman punitive expeditions; in this part of the relief, Germanic captives are being slaughtered en masse.

This complacency arose from the fact that the (mainly Germanic) peoples who lived

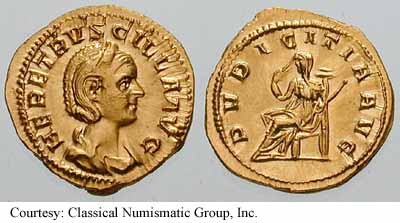

in barbarico were divided into small tribal policies based on clan and family ties that posed no threat militarily to Rome. But paradoxically, the drift towards greater military competence amongst Rome’s northern neighbors was only exacerbated by direct Roman interference in their political life. Roman dogma held that all “barbarians” were dangerous and that it was therefore best to keep them at odds with one another as much as possible. To keep “barbarian” leaders in a state of mutual hostility, Roman emperors frequently subsidized some kings directly. This support built up royal prestige and hence governing capacity, while reducing the importance of those leaders who were denied the same support. This type of interference allowed emperors to manage not just relations between these peoples and the empire, but also the relationships between different “barbarian” groups. Along the northern border of the empire, access to Roman luxury goods was often as important as the items themselves. The ability to acquire wealth meant the ability to redistribute it, and to be able to give gifts enforced a leader’s own social dominance. In other words, conspicuous wealth translated into active power. For these purposes, gold and silver were especially important, and were the dominant medium for storing wealth. Distribution patterns of silver coinage beyond the Roman border tend to vary according to the political importance of particular regions at particular times: in Germania, for instance, we find a huge concentration of 70,000 silver

denarii in just a few decades between the reigns of Marcus Aurelius and Septimius Severus, when campaigning along that frontier was regular and intense. What that and other evidence demonstrates is that the emperors and their governors regularly manipulated political life in

barbaricum through economic subsidy. Yet this strategy, however necessary it might seem within the mental paradigms of Roman government and however effective it might be, was also fraught with dangers.

Roman soldiers executing POWs, column of Marcus Aurelius, Rome.

It started to fail during the reign of Marcus Aurelius. Among the northern peoples that the Romans called

Germani, the largest and most powerful one had been that of the Marcomanni. In 165 CE, the victorious

vexillationes of the European legions returned to their bases from the East, carrying with them a devastating epidemic that today scholars consider to have been the first appearance of smallpox in the Mediterranean basin. And as could be expected, one of the groups which were hit the worst was precisely the army, which became critically weakened in numbers. The Marcomanni and their allies seized the opportunity, and they invaded the upper Danubian provinces, endangering Italy itself. It took Marcus Aurelius more than 20 years of almost constant warfare to crush his foes (in the case of the Marcomanni, they never recovered from Roman reprisals).

Raising the status of some leaders above that of their neighbors and natural peers could provide them with both means and motive for military action that they would otherwise have lacked. Leaders buttressed by Roman subsidy were able to attract more warrior clients into their following, thus enlarging the political groups they led. As it happened with Roman soldiers, barbarian warriors were better behaved when kept employed at the tasks for which they were suited. Fighting one’s “barbarian” neighbors was useful in this respect, but nearby Roman provinces, with their accessible wealth and a road system that made it easy for raiding parties to move rapidly about, became a hugely tempting target when imperial attentions were preoccupied elsewhere. The attractions of Roman wealth, combined with the hostility that was undoubtedly generated by periodic incursions of Roman soldiers, meant that there were strong structural reasons for attacks on the Roman northern border. These same structural reasons might occasionally inspire a particularly powerful “barbarian” king to conceive more grandiose plans.

The larger the force, the most probabilities for success it had whether against other “barbarian” groups or against Rome, so this new social dynamic soon led to a catastrophic development for Rome: large loose confederations appeared where until then there had been solely small tribal groups. Some of their names (as reported by Graeco-Roman authors) have preserved the nature of their mixed and unrooted nature:

Alamanni (all the men),

Iuthungi (the young ones, perhaps a subgroup of the Alamanni),

Franci (probably coming from a Germanic root meaning "fierce", "bold" or "insolent"). These confederations were not centralized entities by any means, and they did not recognize anything remotely resembling a sole monarch in most cases; in the IV century the Franks and Alamanni were still described as being led by several

reges or

iudices, each of which was probably the leader of one war band whose main worry was the upkeep and preservation of its own group of followers. Still, this development allowed the Germanic peoples to put in the field forces much larger than just a century before.

This development is first attested in the upper Danube, where the name

Alamanni is first reported by Cassius Dio in his description of Caracalla’s 213 CE campaign. The

Franci are named for the first time in the 250s CE, same as the

Iuthungi. It’s probably not a coincidence that they appeared for the first time in this decade, when the Roman empire entered a deep crisis, with its armies decimated by plague and civil wars, and the fiscal difficulties that the empire experienced had possibly caused a sharp drop (or the complete elimination) of subsidies. In the Rhine and upper Danube borders, the process seems to have been relatively quick and complete, probably because it was in this area where Germanic peoples had been most divided into smaller tribal units.

In the middle Danube, the process was very slow or non-existent in the III century. The Quadi were still the main problem for Roman forces here, together with the Sarmatian Iazyges. The only newcomers to this scene were the Vandals, an eastern Germanic group possibly based around modern Silesia and Moravia which launched several raids on Pannonia.

But it was on the lower Danube where the greatest danger for Rome arose. In this area, the traditional foes of Rome were the Carpi (also known as “free Dacians”), who launched continuous raids against Dacia, and the Sarmatian Roxolani. But now, a new and very powerful “barbarian” group appeared there. This group was the Goths. Historians, like David S. Potter, are somewhat reluctant to call these newcomers with the name “Goth” in the III century CE. The reluctance is perhaps understandable, because the Goths are associated in the archaeological record with the Chernyakhov culture in Ukraine, which is only archaeologically attested in the IV century CE, and not earlier.

Then there’s also the issue of linguistics. Greek and Roman authors of the III century CE did not use the word “Goth” to refer to this people until the decade of the 270s CE. Unfortunately, no contemporary records of the III century Gothic wars has survived. We know that the Greek author Dexippus of Athens wrote a history of the Gothic wars from 238 CE to 270 CE, which was titled

Skythica, and was used as a source by many later authors who wrote about these events, especially by the SHA, Zosimus and Zonaras.

He was a contemporary of the events and he was personally involved as an Athenian magistrate in the fight against Germanic invaders and the defense of Athens and Greece. Through the fragments that have survived from his

Skythica, Dexippus is considered by modern scholars as the main available source for events. And Dexippus never called these new foes “Goths”. Instead, he used the archaic term “Skythai” for them (borrowed from Herodotus and Thucydides). The late V century CE author Zosimus called them “Boranoi” (strange, as by then the word “Goth” was well in use), and they were called “Boradoi” by the III century CE Christian author Gregory of Neocaesarea.

In my opinion, that’s perhaps a bit too much caution, because there’s evidence for the use of the word “Goth” and of names in Gothic language by members of this people in the III century CE. The earliest appearance of the word “Goth” in Latin is on an inscription from the Roman province of Arabia that’s dated to the reign of Septimius Severus. This inscription, found at I’nāt on the southern Hauran proclaims the monument of a certain Guththa, son of Erminarius, who is described as the commander of the tribal troops (

gentiles, a word used by the Romans as synonymous with

numeri), stationed among the Mothani, which were the natives of Motha, modern Imtān. The names

Guththa and

Erminarius have been shown without doubt to be Germanic ones, and so we’re dealing here with a commander of

Gothi gentiles. But not all scholars accept that these names, although undoubtedly Germanic, are Gothic names. The inscription is dated (in the local era of the province) to 208 CE. This also raises the question that the Romans had contact with the Goths much earlier than 238 CE and that already Septimius Severus was employing them as mercenaries in the East (meaning that it’s very possible that Caracalla and Gordian III did the same in their own eastern campaigns). Also, Dexippus names as leaders of the

Skythai (at least in the surviving fragments) two people with clear Gothic names:

Ostrogotha and

Cniva.

The main problem when dealing with the origins (or, to use the word conined by the Austrian scholar Herwig Wolfram,

ethnogenesis) of the Goths, the only extant ancient source that deals with the matter at large is the VI century CE Jordanes. Jordanes was a Goth who wrote in Constantinople in the VI century CE during the reign of Justinian a Latin book titled

De origine actibusque Getarum ("The Origin and Deeds of the Getae/Goths”, usually abbreviates as

Getica), which was a history of the Goths. This book was an epitome of a much more extensive

History of the Goths written in Latin by the Roman officer Cassiodorus (

Flavius Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus Senator), who was Roman consul and

magister officiorum under the Ostrogothic king of Italy Theoderic the Great.

This work by Cassidorus was not intended to be an “objective” work (if such a notion even existed in those times), but rather a courtly history intended to exalt the Theoderic’s people and especially his own family the Amali by linking it to the legendary origins of the Goths. In other words, it was a work with a clear and deliberate political agenda, which was its primary objective. In this sense, the accuracy of the

Getica as a source for a realistic history of the Goths is quite disputed among scholars, especially because its contents seem to be a crude rehash by Cassiodorus of works by previous Latin and Greek authors, containing gross major anachronistic mistakes and outright and bizarre fabrications. The Austrian historian Herwig Wolfram though believes that there might be a kernel of truth in Cassiodorus’ account; a

Traditionskern which was essential for the existence of the group known historically as “Goths”. Wolfram and his followers argue that barbarian ethnicity was not a matter of genuine descent-communities, but rather of

Traditionskerne (“nuclei of tradition”), small groups of aristocratic warriors who carried ethnic traditions with them from place to place and transmitted ethnic identity from generation to generation; larger ethnic groups coalesced and dissolved around these nuclei of tradition in a process of continuous becoming or ethnic reinvention that Wolfram named ethnogenesis. Because of this, “barbarian” ethnic identities were evanescent, freely available for adoption by those who might want to participate in them.

To summarize, the

Getica puts the legendary origin of the Goths in a land called

Scandza, from where a leader called Berig departed with three ships in a legendary past. After crossing the see, they settled in a new land which they called

Gothiscandza, where they grew numerous. And the historicity of the account goes downhill from here, as Berig’s descendants get involved in the Trojan War and even with Egyptian pharaohs (a clear attempt by the Roman Cassiodorus to inject some classical “respectability” into the historical record of the Goths; Roman authors writing for the Frankish kings also fabricated similar tales); the

Getica does not regain any plausibility until it describes the first encounters of the Goths with the Roman army in the III century CE. According to the

Getica, a king named Filimer decided that the now too numerous Goths had to leave

Gothiscandza and settle in a new region called

Oium or

Aujum, which would correspond with what the Greeks and Romans called

Scythia (roughly corresponding with modern Ukraine and southern Russia between the Carpathians and the Volga, the area also known as the Pontic steppe).

Landscape of Polish Kashubia in eastern Pomerania, which would have been perhaps the Gothiscandza of the Getica.

Wolfram and other scholars believe that this “kernel” of truth could preserve the memory of what would have been in effect a group of migrant adventurers who originated from Scandinavia and settled in the southern Baltic coast, where the process of ethnogenesis of the people that would become the Goths began. Many scholars have been tempted to associate these proto-Gothic migrants who settled in the southern Baltic coast with the Wielbark culture, attested archaeologically in eastern Pomerania and Prussia from the I century CE to the first half of the III century CE. The Wielbark culture shows affinities with contemporary Scandinavian cultures, especially in burials and sacred places, and is considered to be thus at least under heavy Germanic influence. But it’s quite symptomatic that, while some historians seem willing to identify this culture with the proto-Goths and the predecessors of other East Germanic peoples closely linked to them like the Gepids and Rugii, archaeologists are far more skeptical and some historians (like Michael S. Kulikowski) share their scepticism. The Wielbark culture’s archaeological sites show a tendency to expand to the southeast along the course of the Vistula river, and by the early III century many of the oldest settlements nearer to the Baltic were abandoned. The problem for archaeologists is that this sudden disappearance of sites associated to the Wielbark culture does not correspond with the appearance of a new cultural complex with clear links to it in Ukraine and Moldova where the Goths appear “suddenly” in the early III century CE. The Chernyakhov culture, clearly associated to the Goths, is not attested until the IV century CE, and shows little or no material links with the Wielbark culture, which altogether makes archaeologists very reluctant to draw easy conclusions. Archaeological evidence in the Swedish province of Östergötland suggests a general depopulation during this period but again there is no clear evidence that this translated into a substantial emigration out of Scandinavia into eastern Pomerania and western Prussia, and thus the Goths could very well have originated in continental Europe,as Kulikowski thinks.

A stone circle in Kashubia (northern Poland) associated with the Wielbark culture.

A stone circle from Närke, Sweden.

Some historians though (like Wolfram) have less trouble with it, and they see in this archaeological record a confirmation (in very broad lines) of Cassiodorus’ record. They also seek support for this theory in linguistic similarities, etymologies (despite Wolfram’s cautions against them in the introduction to his

History of the Goths) and some parts of the

Getica that indeed seem to show a detailed knowledge of Scandinavia (but which in turn could have been borrowed by Cassiodorus from now lost previous Graeco-Roman sources).

In my opinion, the etymology is in this case strong enough to suggest that the original kernel of the Goths came indeed from Scandinavia, and more specifically from southern Sweden. When describing

Scandza, the

Getica says that there were three tribes living there called the

Gautigoths (which could correspond to the

Geatas/Gautar living in western Götaland by the Göta älv river), the

Ostrogoths (which if it’s not one of Cassiodorus’ fabrications could perhaps correspond to the

Geatas/Gautar who inhabited what is today the Swedish province of Östergötland) and

Vagoths (which could correspond to the

Gutar who inhabited the island of Gotland).

Of these lands, the origin of the Goths which according to the

Getica crossed the Baltic and settled in

Gothiscandza could have been the island of Gotland, as the

Gutasaga, written down in the XIII century states that:

over a long time, the people descended from these three multiplied so much that the land couldn't support them all. Then they draw lots, and every third person was picked to leave, and they could keep everything they owned and take it with them, except for their land. … they went up the river Dvina, up through Russia. They went so far that they came to the land of the Greeks. … they settled there, and live there still, and still have something of our language.

In ancient runic inscriptions dated to the IV century in Ukraine, Moldova and Romania, the Goths referred to themselves as

Gut-þiuda (commonly translated as “Gothic people”) or as

Gutans. The Geats (the original Germanic people which inhabited Götaland) were called

Gēatas in Old English, and

Gautar in Old Norse. In the case of the inhabitants of the island of Gotland, the etymology is still more suggestive, for the Old West Norse name for them is

Gotar, and its equivalent in Old East Norse is

Gutar; both terms are used without distinction to refer both to Gotlanders and Goths. Ptolemy referred to them as

Goutai in the II century CE.

Pliny and Tacitus described in their works that a people called the

Gutones lived at the estuary of a river in the Baltic sea, and this could be a direct reference to the Goths who’d settled in

Gothiscandza, and to the people of the Wielbark culture that existed in that place in Tacitus’ time.

If we then consider that the people that formed the Wielbark culture came from Scandinavia, this does not mean that this was a full-scale colonization like in the American West. Most probably, a small Scandinavian warrior elite imposed its rule over the original population of the area. Before the establishment of the Wielbark culture, the area around the mouth of the Vistula was occupied by the Oksywie culture (II century BCE – early I century CE); scholars do not associate the Oksywie culture with any ethnicity or tribal group. The Roman author of the I century CE Pliny the Elder placed a people called

Venedi (which later scholars have hypothetically classified as one of the proto-Slavic groups, related to the later Wends) living along the Baltic shore, and named them “Sarmatian

Venedi”. The II century CE Alexandrine author Claudius Ptolemy placed a people that he called the “Greater

Ouenedai” living along the entire “Venedic Bay”, which can be deduced from the context to be placed on the southern shore of the Baltic sea, and which could be identified with the Gulf of Gdańsk. In his

Germania, Tacitus also named the

Venedi, although he doubted if they should be classified as

Germani or not. The

Getica still places the

Venedi at the lower Vistula region.

It’s also possible that the Wielbark culture, apart from Goths and Venedi, also included the Germanic

Rugii, attested in this area by Tacitus and Ptolemy. Historians have speculated that the

Rugii moved to Pomerania from southern Norway in the I century CE (based again on etymological similarities); the

Getica names the

Ulmerugi as one of the peoples which were defeated and expelled by the Goths upon their arrival in

Gothiscandza. Further to the southwest, archaeologists have placed another culture known as the Przeworsk culture (III century BCE – V century CE) which covered the middle and upper basins of the Oder and Vistula rivers, and stretched south across the Carpathians to the upper basins of the Dniester and Tisza rivers. The Przewolsk culture is sometimes associated with the Vandals, although it probably included several peoples with different ethnical backgrounds, of which the Vandals were perhaps just one among several. Further to the east, in the area of the Pripet marshes and the middle Dnieper basin, archaeologists place the Zarubintsy culture (III century BCE – I century CE), which is usually (but with the usual uncertainty and lack of evidence) with proto-Slavic peoples, and which showed heavy Scythian and Sarmatian influences from the nearby Pontic steppe.

Cultures in central and eastern Europe in 100 CE.

Burial and ritual places associated with the Wielbark culture don’t include all archaeological sites from the I-III centuries CE in the area, and continuation of practices from the older Oksywie culture is still attested, as well as from the neighboring Przeworsk culture once the sites associated with the Wielbark culture began spreading south along the Vistula valley in areas that had contained previously only sites associated with the Przeworsk culture. Scholars have suggested that the areas which show specifically Wielbark-like burial and cultic sites must’ve been the ones directly settled by the proto-Gothic elite, which were organized in small groups that asserted their political dominance over the original inhabitants, who kept their own rites and customs.

A very significant detail mentioned by Tacitus in his

Germania is that of all the Germanic peoples the

Gothones were a rarity because they were ruled by kings:

Beyond the Lygians dwell the Gothones, under the rule of a king; and thence held in subjection somewhat stricter than the other German[ic] nations, yet not so strict as to extinguish all their liberty. Immediately adjoining are the Rugians and Lemovians upon the coast of the ocean, and of these several nations the characteristics are a round shield, a short sword and kingly government.

Archaeology does not show any hints of centralized kingship in Wielbark culture sites, but in the III century the Goths are described by Greek and Latin authors as being led by kings (like Cniva), which made them specially dangerous, as of all the enemies of Rome during the III century crisis, the Goths were, together with the Sasanians, the only ones able to raise military forces under a unified command on a scale comparable to the one possessed by the Romans.

A very useful comparison that I read once about the character of Gothic rule in eastern Europe was a parallel with the Rus of the IX-X centuries; groups of ambitious, warlike migrants who settled in already inhabited areas and forced the original inhabitants to submit and pay tribute to them; coincidentally both the Goths and the Rus had the same Scandinavian origin in southern Sweden and used the river valleys to expand south to the Black sea coast, ending with attacks against the Roman empire. In both cases, it should be clear that the Rus armies that attacked Constantinople or the Gothic armies that attacked the Roman Danubian border were not formed exclusively by Germanic Goths or Rus; these groups formed only a small leading elite over a vast array of subject peoples from varied origins.

Path of the possible movement of the Goths and the cultures hypothetically associated with them. In green, Götaland, in pink the island of Gotland, in red the maximum expanse of the Wielbark culture in the late II century CE, and in orange the Chernyakhov culture of the IV century CE. In violet, the Roman empire.

By the early III century, the slow southwards expansion of the proto-Goths led them into a large area, which included Ukraine, Moldova and parts of southeastern Poland and Belarus. At the same times, the oldest settlements associated with the Wielbark culture became depopulated. It’s unknown what led the proto-Goths to abandon their lands in the lower and middle Vistula valley (the

Gothiscandza of the Getica). The climatic upheavals associated with the end of the Roman Climate Optimum (RCO) could be one reason, while just the ambition and the possibility to move into richer lands to the south could be another one (notice also that one does not include the other). The end of the RCO and the start of the Roman Transitional Period happened in the middle II century CE century; some scholars have speculated that the movement of the proto-Goths to the southeast could have started to happen around this time, and that the disturbances caused in the inner

barbaricum by this migration could’ve been the one of the reasons for the Marcomannic attack against the Roman empire under Marcus Aurelius.

In any case, the inscription from I’nāt in Roman Arabia states that possibly during the reign of Septimius Severus (193-211 CE), the Goths were already settled near the Roman border, and that for some time its relations with Rome were relatively peaceful. Their new territory included most of the area of the old Zarubintsy culture, and parts of the area of the Przewolsk culture, which still held further west, as well as a large expanse of Pontic steppe which until then had been ruled by Iranian Sarmatian peoples. The Goths must’ve imposed their political dominion over all of them, and just as it had happened with the Zarubintsy culture, they absorbed many cultural Sarmatian traits and customs, especially in military equipment and tactics. The Goths adopted the cavalry warfare that existed in the Eurasian steppe, and its military elite fought on horseback with armor, long sword, Sarmatian

kontos and bows. This again put the Goths aside from all other Germanic peoples, who were predominantly infantry fighters, and who did not put much emphasis in archery, which became extremely important for the Goths as it was for all the steppe peoples. Also, instead of the traditional Germanic longbow, the Goths adopted the more powerful and smaller Scythian bow which had longer range and could be used on horseback.

The Gothic armies that invaded the Roman empire after 238 CE were not formed exclusively by ethnical Goths, as I wrote before; otherwise they would’ve been unable to field the large numbers of men that Graeco-Roman authors ascribe to them unanimously. “Gothic” armies included contingents of subject peoples like Venedi, Sarmatians, Carpi and other Germanic groups that moved into this area with the Goths and whose relationship with the ethnical Goths is unclear. The Gepids are considered to have been a subgroup of the Goths, but the ties of other East Germanic peoples who lived in the area with the Goths like the Burgundians (who lived in the area around the upper Oder and upper Vistula basins), Rugii, Bastarnae (already present in the area in the early II century BCE), the Heruli and the Scirii (who probably moved south into the area along with the Bastarnae in the early II century BCE) are unclear. Some of them like the Gepids and Rugii seem to have moved south with the Goths, but other groups had already been settled there for a long time. Probably, they were all also treated as subject peoples (same as non-Germanic peoples) and were forced to pay tribute to the Goths and contribute to their wars with men.

It’s due to this heterogeneous nature of the Gothic armies that some modern scholars prefer to use the archaic name of “Scythians” (

Skythai) given to them by Dexippus in his imitation of Thucydides’ style, as it has less ethnical implications. In my opinion, that’s going a bit overboard with linguistic carefulness; Roman armies also included many non-Roman units and nobody has ever doubted to call those armies “Roman”. And ironically, many historians who use this “Scythian” terminology to refer to the III century Goths show little care in calling the Sasanian armies “Persians”, when in this case it’s much more justified to raise objections to the label of “Persian”; only the ruling dynasty itself was Persian, but neither the ruling elite and much less the army, was ethnically Persian or led or staffed by Persians.

With a sophisticated military tradition, a united rulership in war and large numbers of available men, the Goths were a formidable enemy for Rome; the most dangerous among all the Germanic peoples and second only to the Sasanians. The straightforward decision by Tullius Menophilus to pay “subsidies” to them in 238 CE reflects a clear respect from the Roman part towards this new enemy, and what they presented as “subsidies” was probably much more like a regular tribute. The Romans stopped subsidies to weak border peoples all the time when it suited them, but they kept paying them to the Goths for ten years when the imperial finances were in a deplorable state and when such an action was deeply resented by the army (the salaries of the troops and officers were paid in increasingly debased silver coinage, but foreign tributes and subsidies were paid in good quality gold coinage, as Dio Cassius bitterly lamented in the case of Caracalla with the Alamanni). It’s also possible that some kind of real subsidy had been in place since earlier times, for the Romans usually recruited

numeri (also called

gentiles) units from foreign peoples with whom they’d signed a friendship treaty; the Romans took over the payment of a regular subsidy and in exchange the foreign people had to furnish the Roman army with armed contingents that usually came with their own weapons and officers and were allowed to fight according to their own custom; this could have been exactly the case of the unit of

Gothi gentiles based at I’nāt, which kept their own leaders Ermanarius and his son Guththa. If this is the case, then the years between 200 and 248 CE saw a sharp and continuous decline in the strength of the Roman position towards the Goths, who from being a friendly and quite inoffensive border people became a real menace able to extort a regular tribute from an increasingly beleaguered empire.

One would think that the impact of the plague would have been a major shot in the arm to the spread of the religion right? Have any historians speculated on the link between the Plague of Cyprian and the rise of Christianity?