6.5. THE END OF THE ARSACID DYNASTY. THE LAST BATTLE BETWEEN THE ARSACIDS AND ROME: NISIBIS 217 CE.

Whatever had happened at Arbela, Ardawān V was now in an impossible situation. In the worst case, if we try to harmonize Dio and Herodian’s accounts, he’d been tricked by Caracalla in a most humiliating way, he’d escaped from death or capture at the last minute, most of his entourage at Arbela had been massacred, the graves of his ancestors had been desecrated and large parts of Adiabene and possibly Media had been looted by the Romans.

This was the worst defeat suffered by an Arsacid king at the hands of the Romans by far, and worse: it was a personal affront of the worst kind, and a direct attack to the fitness of the Arsacids to defend Iran against foreign foes. Who could believe that a

šahanšah who could not even defend his own family could defend the Iranians against foreign attacks? Perhaps Ardawān, or even the House of Arsāk itself (as Walaxš VI had done nothing either, and had probably been in an agreement with Caracalla), had lost the

farr that Ohrmazd and the

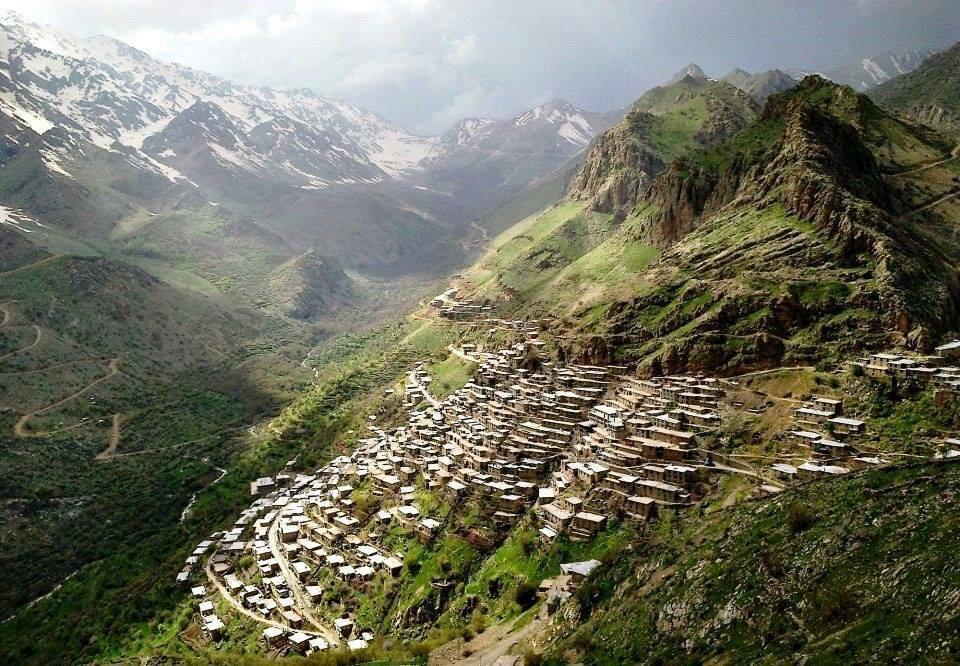

yazdān had invested on them centuries ago. So, probably propelled both by personal hatred and by the sheer necessity of dispelling any doubts about his ability as king and the divine favor bestowed on his house, Ardawān promptly mounted a massive counteroffensive against the Romans by gathering all the forces loyal to him in Iran proper, crossing the Zagros as soon as the passes were free of snow and ice and marching at full speed directly towards the Roman army scattered around in northern Mesopotamia and eastern Syria.

On a certain level, this was a gilded opportunity for the Romans. No Roman general ever had been able to bring a great Arsacid army into a pitched battle, it had always been the Arsacids who, with their superior mobility, had chosen the where and when to engage the Romans, usually coming to close combat with the Romans only when they’ve been thoroughly “softened” by repeated harassing. But this time, Ardawān was coming directly to blows with the Romans, he had neither the will nor the time for the usual indirect Iranian tactics.

Had the Romans been led by another leader, they could have profited from this opportunity, but Macrinus was not exactly a great general. Dio, in the snobbish tone of his last books, gives a less than flattering description of the man:

Cassius Dio, Epitome of Book LXXIX, 11:

Macrinus was a Moor by birth, from Caesarea (Note: in Mauretania Caesariensis, modern northern Algeria), and the son of most obscure parents, so that he was very appropriately likened to the ass that was led up to the palace by the spirit; in particular, one of his ears had been bored in accordance with the custom followed by most of the Moors (Note: this custom was considered intrinsically “barbarian” by Romans and Greeks). But his integrity threw even this drawback into the shade. As for his attitude toward law and precedent, his knowledge of them was not so accurate as his observance of them was faithful. It was thanks to this latter quality, as displayed in his advocacy of a friend's cause, that he had become known to Plautianus, whose steward he then became for a time. Later he came near perishing with his patron (Note: Plautianus had been Severus’ Praetorian Prefect, who fell in disgrace and was executed), but was unexpectedly saved by the intercession of Cilo, and was appointed by Severus as superintendent of traffic along the Flaminian Way. From Antoninus he first received some brief appointments as procurator, then was made prefect, and discharged the duties of this office in a most satisfactory and just manner, in so far as he was free to follow his own judgment.

Herodian gives a somewhat more impartial portrait of the man:

Herodian, 4.12.1:

Caracalla had two generals in his army: Adventus, an old man, who had some skill in military matters but was a layman in other fields and unacquainted with civil administration; and Macrinus, experienced in public affairs and especially well trained in law. Caracalla often ridiculed Macrinus publicly, calling him a brave, self-styled warrior, and carrying his sarcasm to the point of shameful abuse.

When the emperor learned that Macrinus was overfond of food and scorned the coarse, rough fare which Caracalla the soldier enjoyed, he accused the general of cowardice and effeminacy, and continually threatened to murder him. Unable to endure these insults any longer, the angry Macrinus grew dangerous.

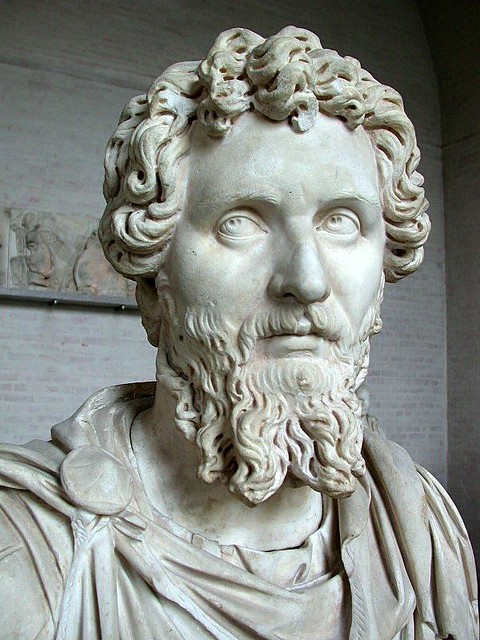

Marcus Opellius Macrinus.

The Praetorian Guard was usually led by two Praetorian Prefects (it was an old Roman custom to duplicate posts); normally one of them was a man of military experience (thus the one who really led the Praetorians in battle) and the other was a juridical expert, who acted as the emperor’s main counsellor in legal matters. Herodian’s text makes clear that Macrinus was the “juridical” prefect, and thus a man with little or no experience in military affairs.

Macrinus was also in a very, very delicate situation. He had orchestrated the murder of an emperor who was idolized by the troops in the middle of an ongoing campaign, and if he wanted to survive, he needed to convince the troops that he’d not been involved in the murder of Caracalla and that he was a valid military leader.

In the first task he more or less succeeded. Luckily for him, no other commanders came forward to claim the purple, and the tribunes of the Praetorian Guard, who probably were also part of the plot, first offered the purple to Adventus (

Marcus Oclatinius Adventus, the other Praetorian Prefect), who refused, and then to Macrinus. Macrinus (according to Dio) then displayed for four days the by then traditional comedy of refusing the throne, until finally “under pressure of the troops”, and “for the good of the

res publica” he assumed the title of

Augustus. The troops accepted Macrinus mostly because they needed an emperor to lead them in battle as soon as possible, as Ardawān was approaching quickly with a huge army.

He duly informed the Senate in Rome of his appointment as

Augustus by the army, and the venerable assembly was aghast at the news: not only was Macrinus a man of most humble origins, but he was not a senator, but an equestrian. It was the first time ever that an emperor had not been chosen from among the ranks of the senatorial

ordo. It was a prelude of things to come.

Macrinus also took great care to give a state funeral to Caracalla and sent his ashes to Rome to be buried, and he also avoided taking any reprisals against Caracalla’s relatives and friends (this was to reveal itself later as a fatal mistake), refused to take reprisals against Caracalla’s informers and spies and asked the Senate to deify him (two acts that disappointed and enraged the conscript fathers). Herodian gives a detailed account of the events (the part of these events corresponding to Dio has arrived to us in a very fragmentary state):

Herodian, 4.14.1-8:

After Caracalla's death, the bewildered soldiers were at a loss as to what to do. For two days they were without an emperor while they looked for someone to fill the office. And now it was reported that Artabanus was approaching with a huge army, seeking a legitimate revenge for the Parthians whom Caracalla had murdered under a truce and in time of peace.

The army first chose Adventus as their emperor because he was a military man and a praetorian prefect of considerable ability; he declined the honor, however, pleading his advanced age. They then decided upon Macrinus, influenced by their tribunes, who were close friends of the general and were suspected of having been involved in the plot against Caracalla. Later, after Macrinus' death, these tribunes were punished, as we shall relate in the pages to follow.

Macrinus thus received the office of emperor not so much because of the soldiers' affection and loyalty as from necessity and the urgency of the impending crisis.

While these events were taking place, Artabanus was marching toward the Romans with a huge army, including a strong cavalry contingent and a powerful unit of archers and those mail-clad soldiers who hurl spears from dromedaries.

When the approach of Artabanus was reported, Macrinus called the soldiers together and addressed them as follows: "That all of you regret the passing of such an emperor, or, more accurately, fellow soldier, is hardly surprising. But to endure misfortunes and disasters with equanimity is the part of intelligent men.

Truly the memory of Caracalla is locked in our hearts, and to those who come after us will be handed down this memory, which will bring him everlasting fame for his great and noble deeds, his love and affection for you, and his labors and comradeship with you. But now it is time for us, since we have paid the last of the prescribed honors to the memory of the dead and have performed his funeral rites, to look to the present emergency.

You see the barbarian with his whole Eastern horde already upon us, and Artabanus seems to have good reason for his enmity. We provoked him by breaking the treaty, and in a time of complete peace we started a war. Now the whole Roman empire depends upon our courage and loyalty. This is no quarrel about boundaries or river beds; everything is at stake in this dispute in which we face a mighty king fighting for his children and kinsmen who, he believes, have been murdered in violation of solemn oaths.

Therefore let us take up our arms and our battle stations in the customary Roman good order. In the fighting, the undisciplined mob of barbarians, assembled only for temporary duty, may prove its own worst enemy. Our battle tactics and our stern discipline, together with our combat experience, will insure our safety and their destruction. Therefore, with hopes high, contest the issue as it is fitting and traditional for Romans to do.

Thus will you repel the barbarians, and by winning a great and glorious reputation you will make it clear to the Romans and to all men - and you will likewise confirm that previous victory - that you did not deceive the barbarians by fraudulently and treacherously breaking your treaty with them, but that you conquered and won by force of arms."

Dio, increasingly bitter in these last books of his work, spent a good part of Book LXXIX criticizing Macrinus for his obscure origins, his lack of culture and education (curious accusation, when he was a jurist) and his poor choices in appointments. One of these tirades is particularly interesting, as it makes clear that Adventus was rewarded for his part in the plot with the post of Urban Prefect in Rome and his advancement to the rank of senator:

Cassius Dio, Epitome of Book LXXIX, 14:

Another thing for which many criticized him was his elevation of Adventus. This man had first served in the mercenary force among the spies and scouts, and upon quitting that position had been made one of the couriers and appointed their leader, and still later had been advanced to a procuratorship; and now the emperor appointed him senator, fellow-consul, and prefect of the city, though he could neither see by reason of old age nor read for lack of education nor accomplish anything for want of experience. The reason for the advancement of Adventus was that he had made bold to say to the soldiers after the death of Caracallus: "The sovereignty belongs to me, since I am older than Macrinus; but since I am extremely old, I yield it to him." Yet it seemed that he must be jesting when he said this, and that Macrinus must be jesting, too, when he granted the highest dignity of the senate to such a man, who could not even carry on a respectable conversation when consul with anyone in the senate and who accordingly on the day of the elections feigned illness. Hence it was not long until Macrinus assigned the oversight of the city to Marius Maximus in his stead; indeed, it looked as if he had made Adventus city prefect with the sole purpose of polluting the senate-chamber, inasmuch as the man had not only served in the mercenary force and had performed the various duties of executioners, scouts, and centurions, but had furthermore obtained the rule over the city prior to performing the duties of the consulship, that is, had become city prefect before being senator. Macrinus had really acted thus in the case of Adventus with the purpose of throwing his own record into the background, since he himself had seized the imperial office while still a knight.

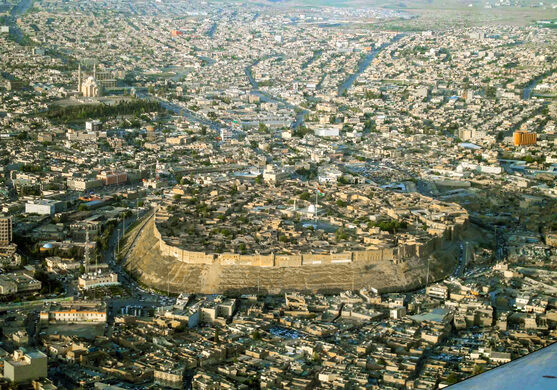

For further precaution, Macrinus also appointed his 9-year-old son Diadumenianus as Caesar (and thus his successor). Now, Macrinus only had to manage the issue of Ardawān`s quickly approaching army. The Roman army (which we must assume was the same army that Caracalla had led, so for the numbers see my previous post) assembled near the fortified city of Nisibis, capital of Roman Mesopotamia and there the two armies met at an undetermined date in the summer of 217 CE.

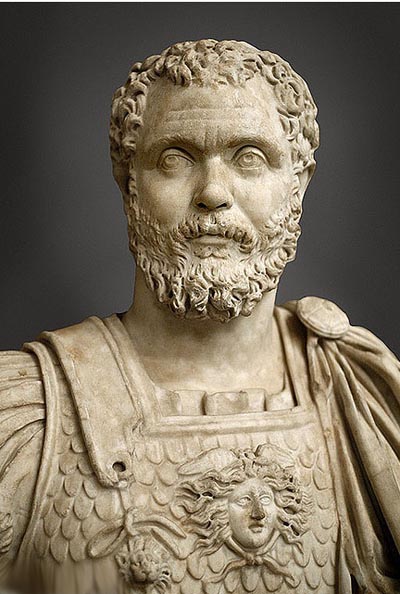

Marcus Opellius Diadumenianus.

Dio’s record of the battle has arrived to us badly damaged, and is of little use to reconstruct the events of the battle, although he supplies some details lacking in Herodian’s report, which has survived complete.Let’s see Dio’s account first.

Cassius Dio, Epitome of Book LXXIX, 26-27:

Macrinus, perceiving that Artabanus was exceedingly angry because of the way he had been treated and that he had invaded Mesopotamia with a large force, at first of his own accord sent him the captives and a friendly message, urging him to accept peace and laying the blame for the past upon Tarautas (Note: one of the derogatory nicknames Dio used for Caracalla). But Artabanus would not entertain this proposal and furthermore bade him rebuild the forts and the demolished cities, abandon Mesopotamia entirely, and make reparation for the injury done to the royal tombs as well as for other damage. For, trusting in the large force that he had gathered and despising Macrinus as an unworthy emperor, he gave free rein to his wrath and hoped even without the Roman's consent to accomplish whatever he desired. Macrinus had no opportunity even for deliberation, but encountering him as he was already approaching Nisibis, was defeated in a battle that was begun by the soldiers in a struggle over the water supply while they were encamped opposite each other. And he came near losing his very camp; but the armour-bearers and baggage-carriers who happened to be there saved it. For in their confidence these rushed out first and charged upon the barbarians, and the very unexpectedness of their opposition proved an advantage to them, causing them to appear to be armed soldiers rather than mere helpers. But . . . . . . . . . . . . . . both then not . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . the night . . . . . . . . . . . . . . the legions? . . . . . . . . . . and the Romans . . . . . . . . . . . . and the enemy the noise . . . . . . . . . . . . . . of them . . . . . . . . . . . . . . suspected . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . them . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . the Romans . . . . of the barbarians . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . overcome by their numbers and by the flight of Macrinus, became dejected and were conquered. And as a result . . . . . . Mesopotamia, especially . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Syria . . . . . . . . . . . . . . These were the events that took place at that time; and in the autumn and winter, during which Macrinus and Adventus became consuls, they no longer came to blows with each other, but kept sending envoys and heralds back and forth until they reached an agreement. For Macrinus, both because of his natural cowardice (for, being a Moor, he was exceedingly timorous) and because of the soldiers' lack of discipline, did not dare to fight the war out, but instead expended enormous sums in the form of gifts as well as money, which he presented both to Artabanus himself and to the powerful men around him, the entire outlay amounting to two hundred million sesterces. And the Parthia was not loath to come to terms, both for this reason and because his troops were exceedingly restive, due to their having been kept away from home an unusually long time as well as to the scarcity of food; for they had no food supplies available, either from stores previously made ready, or from the country itself, inasmuch as the food either had been destroyed or else was in the forts. Macrinus, however, did not forward a full account of all their arrangements to the senate, and consequently sacrifices of victory were voted in his honour and the name of Parthicus was bestowed upon him. But this he declined, being ashamed, apparently, to take a title from an enemy by whom he had been defeated.

Moreover, the warfare carried on against the Armenian king, to which I have referred, now came to an end, after Tiridates had accepted the crown sent him by Macrinus and received back his mother (whom Tarautas had imprisoned for eleven months) together with the booty captured in Armenia, and also entertained hopes of obtaining all the territory that his father had possessed in Cappadocia as well as the annual payment that had been made by the Romans. And the Dacians, after ravaging portions of Dacia and showing an eagerness for further war, now desisted, when they got back the hostages that Caracallus, under the name of an alliance, had taken from them.

So, what can be learnt from Dio’s account? One, that Macrinus first tried to negotiate a peace with Ardawān before the battle, but this attempt failed. Two, that the battle was a Roman near-defeat due to the worthless leadership and personal cowardice of Macrinus “the Moor”. Three, that Macrinus had to buy peace with Ardawān (200 million sesterces), release all captives (Parthians and Armenians) and allow Tiridates to be crowned as king of Armenia. Dio also gives the reason for Ardawān’s change of opinion regarding a negotiated peace the fact that his troops had become “restive” after spending a long time away from their homelands, and the scarcity of supplies (two of the key weaknesses of the Arsacid military system). Dio states that this happened “in the autumn and the winter”, which means that after the battle Macrinus and Ardawān opened negotiations, which stretched until Ardawān’s army melted away. But as for the battle itself, Dio’s mutilated account gives us practically no information. Let’s read now Herodian’s account:

Herodian, 4.15.1-9:

Artabanus appeared at sunrise with his vast army. When they had saluted the sun, as was their custom, the barbarians, with a deafening cheer, charged the Roman line, firing their arrows and whipping on their horses. The Romans had arranged their divisions carefully to insure a stable front; the cavalry and the Moorish javelin men were stationed on the wings, and the open spaces were filled with light-armed and mobile troops that could move rapidly from one place to another. And so the Romans received the charge of the Parthians and joined battle.

The barbarians inflicted many wounds upon the Romans from above, and did considerable damage by the showers of arrows and the long spears of the mail-clad dromedary riders. But when the fighting came to close quarters, the Romans easily defeated the barbarians; for when the swarms of Parthian cavalry and hordes of dromedary riders were mauling them, the Romans pretended to retreat and then they threw down caltrops and other keen-pointed iron devices. Covered by the sand, these were invisible to the horsemen and the dromedary riders and were fatal to the animals.

The horses, and particularly the tender-footed dromedary, stepped on these devices and, falling, threw their riders. As long as they are mounted on horses and dromedary, the barbarians in those regions fight bravely, but if they dismount or are thrown, they are very easily captured; they cannot stand up to hand-to-hand fighting. And, if they find it necessary to flee or pursue, the long robes which hang loosely about their feet trip them up.

On the first and second days the two armies fought from morning until evening, and when night put an end to the fighting, each side withdrew to its own camp, claiming the victory. On the third day they came again to the same field to do battle; then the barbarians, who were far superior in numbers, tried to surround and trap the Romans. The Romans, however, no longer arranged their divisions to obtain depth; instead, they broadened their front and blocked every attempt at encirclement.

So great was the number of slaughtered men and animals that the entire plain was covered with the dead; bodies were piled up in huge mounds, and the dromedaries especially fell in heaps. As a result, the soldiers were hampered in their attacks; they could not see each other for the high and impassable wall of bodies between them. Prevented by this barrier from making contact, each side withdrew to its own camp.

Macrinus knew that Artabanus was making so strong a stand and battling so fiercely only because he thought that he was fighting Caracalla; the barbarian always tires of battle quickly and loses heart unless he is immediately victorious.

But on this occasion the Parthians resolutely stood their ground and renewed the struggle after they had carried off their dead and buried them, for they were unaware that the cause of their hatred was dead. Macrinus therefore sent an embassy to the Parthian king with a letter telling him that the emperor who had wronged him by breaking his treaties and violating his oaths was dead and had paid a richly deserved penalty for his crimes. Now the Romans, to whom the empire really belonged, had entrusted to Macrinus the management of their realm.

He told Artabanus that he did not approve of Caracalla's actions and promised to restore all the money he had lost. Macrinus offered friendship to Artabanus instead of hostility and assured him that he would confirm peace between them by oaths and treaties. When he learned this and was informed by envoys of Caracalla's death, Artabanus believed that the treaty breaker had suffered a suitable punishment; as his own army was riddled with wounds, the king signed a treaty of peace with Macrinus, content to recover the captives and stolen money without further bloodshed.

The Parthian then returned to his own country, and Macrinus led his army out of Mesopotamia and hurried on to Antioch.

Herodian’s text gives much more details about the battle itself. It says nothing about a previous skirmish, and implies that both armies had pitched camp in front of each other to fight a frontal battle. The terrain favored the Arsacid side because it was an open plain free of obstacles, but probably the Romans (according to Dio, and as was Roman standard practice) had some sort of fortified encampment behind them. What shows poor leadership on Macrinus’ side though is that, having had lots of time to choose the battlefield and prepare for the battle, he had neglected to build any kind of field fortifications.

Herodian states that the battle lasted three days, that “the Parthians” had a sizeable numerical advantage over the Romans (given the probable large numbers of the Roman army as discussed in the previous post, this meant that Ardawān had thrown into the fight practically every force he had available) and that they attacked at dawn of the first day, which is quite logical in an army numerically superior and seeking a decisive victory: they probably wanted to take maximum advantage of daylight hours. But Ardawān here did not show either outstanding qualities as a field commander, because despite having the advantage of numbers, he did not try to encircle the flanks of the Roman force until the third day, after having suffered grievous losses the two previous days. Instead, he fought the battle as a frontal encounter, to the Romans’ benefit.

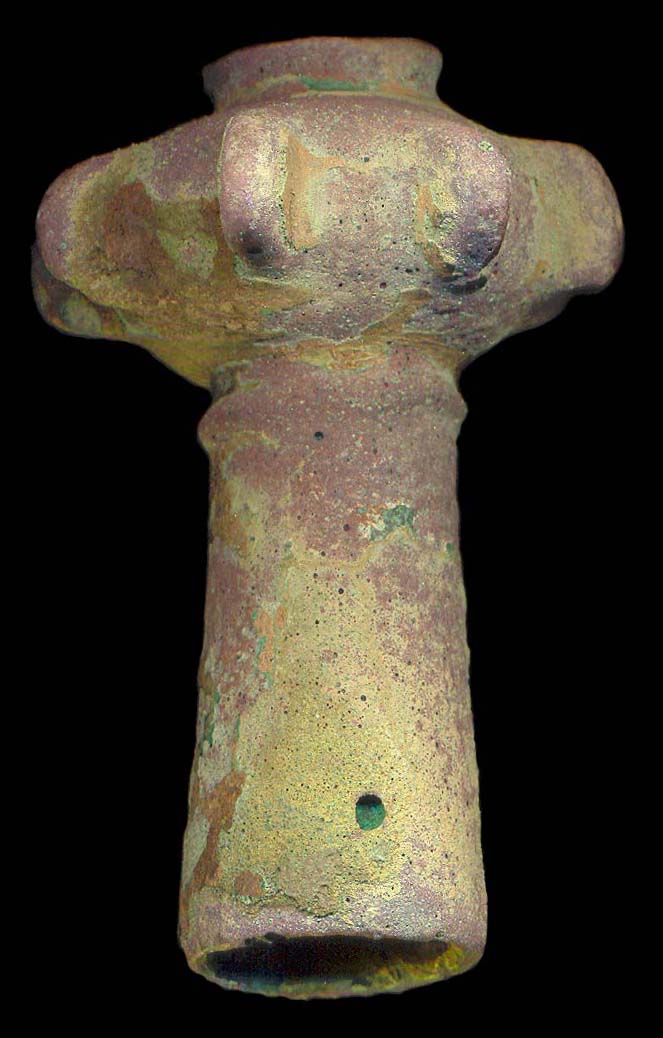

The description by Herodian of the Roman array implies that the Roman heavy infantry was deployed in main bodies separated by spaces occupied by light infantry. The light infantry was to be used to sally forth in case that the Iranian cataphracts charged the Roman heavy infantry in got bogged down in front of the legionaries; their task would be to attack the cataphracts (or more likely their horses) in close combat, and to retreat again to safety behind the heavy infantry if the cataphracts retreated and another charge of cavalry came against the Roman line. It should be stated that despite Herodian’s (and other Greek and Roman authors) flamboyancy about these tactics, and his statement that “the Parthians” were weak and cowardly in close combat, this was a very dangerous activity, because the training and panoply of Arsacid and Sasanian cataphracts included close combat tactics with convincing weapons, like long swords, heavy war maces and pickaxes. Although it’s evident that their main weapon, the long

kontos, was useless in close combat, they were by no means defenseless.

A zurkhāneh in Iran. Still today in these "Houses of Strength" men and boys train in the varzesh-e pahlavāni ("heroic sport"), a tradition that dates back to the Arsacid era.

Head of a Sasanian bronze war mace found in Pakistan.

British reenactor Nadeem Ahmad in the full regalia of a Sasanian commander, VI-VII centuries CE.

Sadly, neither account lets us know how was the Roman heavy infantry arrayed. In his book

Caracalla: A Military Biography, Ilkka Syvänne proposes that the bodies of heavy infantry could have been arrayed in four possible ways:

- As single oblong formations (elongated hollow squares, with the light infantry inside them).

- As double oblong formations, one in front and the other in reserve (as classical war manuals recommended for situations of numerical inferiority and/or enemy cavalry superiority).

- As simple phalanxes, 16 files depth (the classical Hellenistic array, described by Arrian as being used by the Roman army in the II century CE in the East).

- As double phalanxes, each 16 files depth.

Syvänne guesses (correctly in my opinion) that the last two formations would have been more probable, given that during the third day Macrinus kept sending reinforcements to both flanks of the army to avoid being surrounded; with squares this would have been difficult, but with phalanxes it would have been a matter of sending the back ranks into the flanks, weakening the center but without destroying the coherence of the Roman tactical array.

Another proposal by Syvänne (but with does not appear either in Dio or in Herodian) is that given that the Roman cavalry, originally posted in the flanks, disappears from the battle and is not mentioned in the events of the third day, when in theory it should have prevented the outflanking attempts by Ardawān`s forces, is that it met the initial charge of the Iranian cavalry. It’s possible, but it would have been a highly incompetent move by Macrinus (which is not impossible, either), given the overwhelming quantitative and qualitative superiority of the Iranian cavalry.

Nowhere in Dio or Herodian’s texts do they imply that Ardawān’s army deployed infantry, although it’s almost sure that it included infantry.

As for the Arsacid army, Syvänne proposes (again without support from documentary sources, but based on what’s known from the Parthian and Sasanian way of war, through Islamic era treatises and Central Asian art) that it was arrayed in two lines with five bodies each (the most classical array for an Iranian / Central Asian cavalry army), and each of these bodies would have been formed by rhomboid or wedge formations. The first line would have been formed mainly by horse archers and the second line by cataphracts armed with

kontoi.

It’s clear that Herodian did not understand any of these tactical intricacies, because he described “the barbarians” as just launching a frontal charge against the Romans, without further ado. He adds quite correctly that the Roman army suffered considerable damage by the Iranian archery (as was to be expected), and that the legionaries also suffered many casualties from a tactical experiment of Ardawān: cataphracts mounted on dromedaries or camels; apparently, as these animals are taller than horses, this allowed their riders to hit the Roman soldiers more effectively and with impunity from above, although this in turn bears into question which was the effectivity of Roman light infantry; it’s difficult to imagine camels/dromedaries charging with the same speed as a horse, so they must’ve been used with the animal either trotting at low speed parallel to the first rank of legionaries, or completely static. The fact that these cataphracted camels are never mentioned again in Roman or Eastern sources suggests that the experiment was not very successful, and that it was not repeated.

Another interesting point of Herodian’s account is that this time, it was the Romans who managed to fool the Arsacid cavalry with a feigned retreat, and inflicted losses on their cavalry with the use of caltrops (

tribulus in Latin) but not nearly enough as to stop the relentless assaults by Ardawān’s army. But what is most underscored both in Dio and Herodian is the tenacity and ferocity with which the Arsacid army fought, for three consecutive days, with continued frontal assaults against the well-disciplined Roman infantry.

A caltrop.

Dio states clearly that Macrinus lost the battle and fled the battlefield, abandoning his army. Herodian though says nothing of the sort, and implies that it ended in a draw and that both leaders, in view of the losses sustained by both armies, opened peace talks.

Herodian does not offer a timeline for the negotiations as Dio does, but the final result according to him is basically the same: all the prisoners are returned to Ardawān and “the booty” looted by Caracalla is also returned (which could be the same that Dio depicted as a tribute paid by Macrinus).

Nisibis was to be the last battle fought between the Arsacids and Rome. In less than a year, Macrinus and his son were dead and replaced by the colorful emperor Elagabalus, and seven years later Ardawān V died in battle against the army of Ardaxšir I, and the rule of the House of Aršak in Iran came to an end.

Politically, it could be said that both leaders lost the battle. Macrinus, who desperately needed to win a reputation as a successful battle commander to make his soldiers forget their idolized Caracalla, failed miserably. In less than a year, part of the army (led by

Legio III Gallica) rebelled and Macrinus lost the throne, his life and that of his son (ironically, he'd tried to send Diadumenianus to Arsacid territory asking Ardawān to protect the boy, but the boy's companions handed him over to the supporters of Elagabalus). As for Ardawān V, considering the formidable army he’d gathered and the affront he needed to “wash with blood”, he also accomplished little: a costly draw, tempered by some war indemnities and the return of war captives. He also revealed himself as a mediocre commander and worse of all, he’d suffered serious losses among his followers in a moment in which the civil war in Iran was to become three-sided. Most scholars believe that the losses suffered by the forces of Ardawān V and his supporters at Nisibis were key in the success of the revolt by Ardaxšir I.

.jpg)