“Blessings are rare, curses are common.” – attributed to Albrecht von Franken

From Mark Lekaris’ Understanding the Roman Empire, page 122:

1218 began with mixed news for Emperor Thomas.

On one hand, the Emperor was finally on his feet again after his debilitating injury, yet for the rest of his life, Emperor Thomas would limp, needing a litter to travel long distances. The fact their Emperor was back in the saddle, even if he had to be strapped in, was a point of reassurance for the Komnenid armies.

Yet on the other, word had finally been received from the Great Mongol. Genghis Khan had agreed to the proposal from the year before in principal, but the Great Khan had added several stipulations of his own, chiefly that Thomas would

immediately detach 10,000 men from his depleted armies to Mongol service in Central Asia. The Great Khan was already in Bukhara by year’s start, and the redeployment of his

tumen East meant he needed garrisons in lands he’d taken from the Turks. After some deliberation, the Roman emperor acquiesced. Undoubtedly at the insistence of the army who still found his presence rankling, Mehtar Lainez was sent to command this contingent.

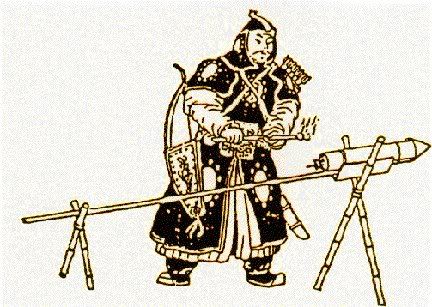

Secretly, however, Lainez had another task, likely from the mind of Thomas himself—catalogue, record, and note every thing he could about the Mongols and the lands they ruled. Lainez would have plenty of time—he and the 10,000 soldiers under his command, mostly from heavily depleted

tagmata, took most of 1218 to march to their posts, mostly garrisons from Bukhara to Heart. Mehtar’s notes were one of the treasure troves of the Imperial Archives for centuries to come, but for Emperor Thomas, one immediate thing proved immensely useful—to this day we are not sure how, but on March 19th, 1219, a note arrived in Sinope addressed to the

Megoskyriomachos himself.

It contained the recipe for a concoction we today know as gunpowder.

Yet we are getting ahead of ourselves.

By February 6th, the city of Jerusalem had been under siege by the armies of Khorbut of Dau for many months, and both food and water supplies were running low. The Prince of Alexandria, likely under advice from Sinope, offered Patriarch Ioannis terms of surrender—if the city opened its gates, no citizen would be harmed, and Ioannis would be allowed to leave the city in peace. Foolishly, Ioannis agreed to these terms, and within the week, “fell” from a tower attached to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

It was here where Khorbut of Dau made his first overt moves towards power in his own right. Rather than sending to Sinope for instructions, Khorbut appointed his own son Thomas as Patriarch, bribing the Metropolitan of Acre to perform a hasty consecration ceremony, then sent word to Sinope the deed had already been done. Additionally, he sent notice he was claiming the title Defender of Jerusalem and the title of

Despotes in his own right. Initially, there was resistance from Sinope, before undoubtedly Albrect von Franken finally succeeded in getting Thomas to agree to the arrangement, on one important condition.

Khorbut would become

Despotes of Egypt only. Instead of granting the Levant to Khorbut, Thomas raised his cousin Prince Michael of Antioch to the position of

Despotes of the Levant (albeit with no territory to rule at the time). While in official correspondence Khorbut seemed pleased with the Emperor’s decision, there can be little doubt that the aged patriarch of House Dau was incensed at his grandson’s decision.

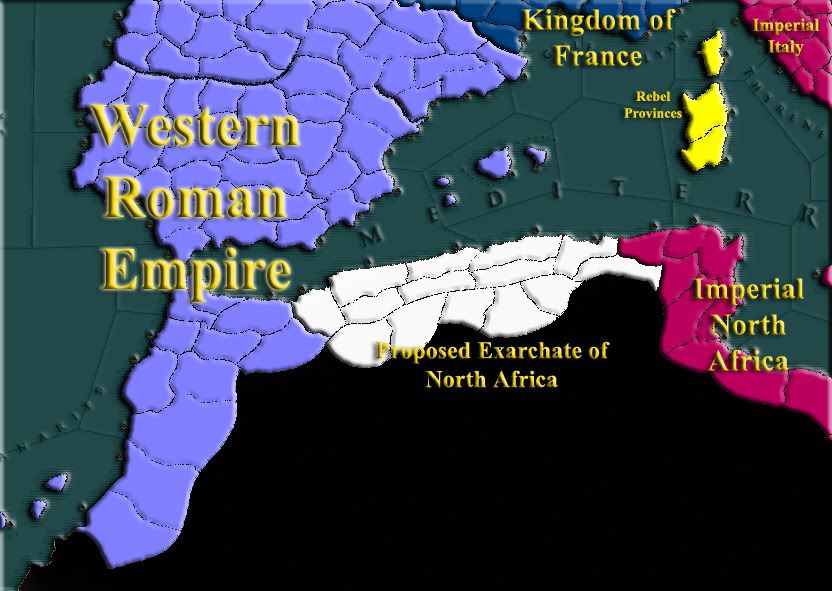

Further to the West, the situation in Italy and North Africa took a series of dramatic turns.

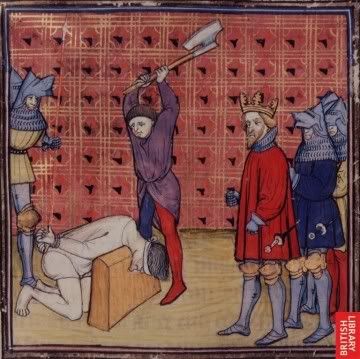

The spring of 1218 finally saw Bardas hold true to his promise to move north with his large army. By the 5th of May, Bardas had relieved the siege of Rome, compelling Buvanelli to withdraw to the north. The quick withdraw of his troops quickly emboldened Buvanelli’s former conquests, and the remnants of the militias of Florence and the other great cities swelled the ranks of Bardas’ army. It wasn’t until August 11th that Buvanelli was finally forced into battle at odds outside of Bologna, and despite the valor and courage of his citizen-army, Buvanelli lost 8,000 out of 22,000 remaining as his army was scattered to the winds by Bardas’

skoutatoi core. Buvanelli was captured in the final rout, and the promising poet was executed by Bardas for his trouble.

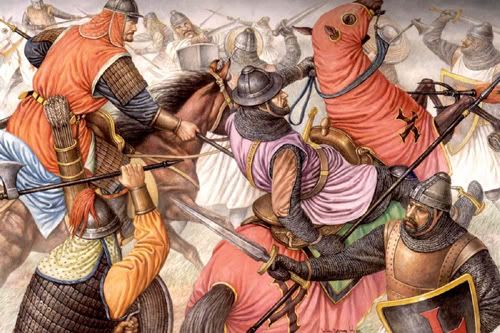

A 14th century depiction of the Battle of Bologna. Notice how the South Italian kataphraktoi are dressed in armor more fitting North Italian knights of the period.

As soon as Buvanelli’s army fell outside of Bologna, the cities of North Italy fell over themselves declaring their support for

Despotes Bardas. As an example, Bardas burned Milan and Verona to the ground, then symbolically had his men dig latrines in the ruins. All of northern Italy quaked—except Venice. The Venetians instead adopted their classic defensive technique—they withdrew from the Italian mainland to their island city, protected by a small squadron of galleys the Venetians knew Bardas could not match. The Prince of Apulia settled himself in for a long siege, ordering his shipmasters in Taranto and Ancona to build a fleet for him as quickly as possible.

Further south in Africa, initially affairs looked bleak for the Komnenid cause, as Muhsin Kosaca’s troops ran rampant across Constantine, Kairuoan, and Leptis Magna. However, on the 8th of July, the Western Emperor’s response finally came—15,000 Spanish Greeks landed outside of Tunis, another 10,000 outside of Constantine. Legend says that Alexios saw a cross in the sky, and was told by God it was his sacred duty to return Carthage to the control of the True Emperor. Considering his later behavior, this historian feels such claims are more rooted in popular superstition than any real “vision” the Western Emperor might have seen.

A painting of the “Vision of Alexios” by Dupree, 1663

Mushin quickly gathered his forces in nearby Kairouan, and believing his 20,000 superior, sought battle outside of Utica. Alexios, however, proves himself as able an heir of his grandfather as Thomas, ambushing Kosaca’s cavalry on the 11th of August, before finally closing for battle on the 13th, where his superior trained force easily crushed the forces of Kosaca, who according to legend was among many who fell by the blade of the reforged

Kyriomachos.

Through the rest of the year, Alexios’ troops liberated the cities of Imperial Africa and Constantine with ease, before laying siege to the cities of Kairouan itself. As his troops took their positions around the former Kosaca capital on the 3rd of November, Alexios sent a dispatch to Sinope—unless Thomas immediately surrendered Constantine as a new

Exarchate under the Spanish Empire

and either financed or conducted an attack against the French, Alexios would claim all of Imperial Africa in the name of the Western Empire.

Alexios’ absence had not gone unnoticed however, as the long-simmering cold war between Alexios and Arnaud exploded into hot.

The situation began just before the start of the year—Andreas sent agents to Pope Celestine in Hereford, loaded with gold and promises of a reunion of churches should he triumph. Andreas could see that with Anatolia under his sway, Thomas held a large, immediate advantage on land, an advantage the usurper was keen to end. After some suitable encouragement, the Pope issued a bull amongst the Latins, stating that God had ordained Andreas Kaukadenos to be the ruler of the Empire of the Greeks, and that it was the duty of every Christian to come to Kaukadenos’ aid. However, Latin Europe was in chaos—Germany was in shambles, Poland and Hungary were gearing themselves ready for the Mongols, after hearing tales from the steppe. Sweden was busily gobbling up Norway, while the Irish were too small and the Scots too far away to matter. Only one Catholic King stood ready to intervene—Arnaud Capet of England and France.

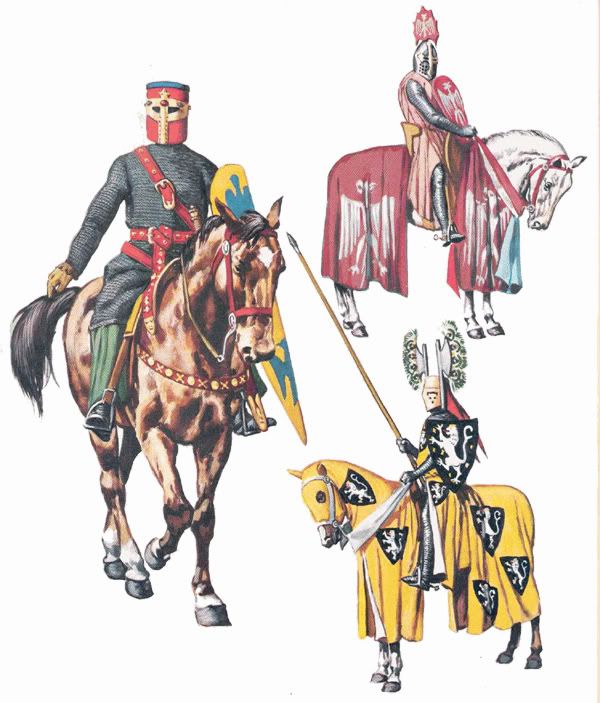

Arnaud Capet, King of France and England

Arnaud was an extremely devout man—supposedly his coup against his cousin Louis had more to do with the young man’s growing hedonism and little to do with gaining actual power. However, after Arnaud took the throne in 1207, the new King set about to vigorously remake the powerful kingdom that Drogo had built. Where Drogo built an empire of soldiers, Arnaud desperately sought to build an Empire of Christ, worthy of serving as protector of the Papacy now ensconced in Hereford. Laws permitting usury were abolished, lands were liberally distributed to the Church, and all the nobility at the court of Paris were required to attend Mass thrice daily, or risk losing court position. Needless to say, while this might have perturbed many who were used to the general liberalities that took place under Drogo, it certainly raised the stance of France in the eyes of the Papacy after the nadir under Drogo II Capet.

Thus, when Pope Celestine made his pronouncement on New Year’s Day, 1218, Arnaud was moved. Immediately, the King took the papal call as a holy mission, a crusade to remove the infamously carnal Komnenids from the position of Christ’s Vice Gerent. The call for feudal levies went to vassals from Lincoln and Nottingham in the north to Toulouse in the south, and by April 3rd, Arnaud’s vast feudal armies were ready to move. The Constable of France, Jean de Auvergene, lead some 15,000 soldiers across the Pyrenees in June, with the goal of striking one part of the carnal menace while he was away. Only the quick thinking of

Exarchs Thrakesios and Malhaz II Komnenos kept Catalonia from French clutches through the summer of 1218, before the Constable’s feudal levy had to return home for fall harvest.

Arnaud’s professional army—mercenaries, soldiers taking the cross when their lords from Germany, Sweden or Scotland refused—sailed from Marseilles in June as well. It was not long before the vast host, 30,000 men and 200 ships, were spotted off of Imperial Sicily.

The news of a vast French fleet sailing arrived in Sinope by the end of July, undoubtedly causing a moment of panic. Where would the French land? Egypt was only lightly defended—Khorbut’s

thematakoi fleet was present, as well as a few thousand soldiers, but little more. These fears proved unfounded, however, as Arnaud adopted the simpler, and far more direct approach than an invasion of a Komnenid weak point.

He sailed to Konstantinopolis itself.

The arrival of the King of France on September 18th was perhaps the event of the decade for the Queen of Cities. Andreas had lavished coin from his cash-strapped treasury on games for the people and opulent gifts for his newly arrived allies. However, if these were meant to impress the pious Arnaud, they failed miserably. From the first day, the French King refused to stay in the opulent splendor of the Blacharnae palace, instead humbly asking the Patriarch for a room at his residence. Instead of attending the great races in the Hippodrome, Arnaud donned sackcloth and went to the

Hagia Sophia, bluntly saying a truly Christian leader would do likewise. Publicly scolded, Emperor Andreas was forced to leave aside his politicking and don sackcloth as well inside those hallowed halls, greatly disturbing the populace of the city that had expected an Emperor to be in the

Kathisma. It was an ominous start to what at first looked to be a winning partnership.

At the same time Kaukdenos and Capet were forming a partnership, another was ending. A minor scheme by Emperor Thomas to land on the Dardanelles peninsula was unraveled due to miscommunication and the chance arrival of a squadron of Venetian ships. Despite the minor scale of the debacle, the Emperor immediately declared that only treason could have undone the operation.

Strategoi Manuel Grimaldi and Demetrios Antiochites were duly arrested, castrated and blinded. They were the first victims who would leave their blood on Thomas II’s hands.

Further to the East, the volatile situation exploded into chaos. With Alaeddin’s declaration of a Kingdom and renouncement of Christianity, war was inevitable, and the

Exarch busily raised levies and prepared to defend against the inevitable assault from the 30,000 battle-hardened

tagmata of

Megos Domestikos Mahmud of Byzantion. Alaeddin’s reconversion brought many of the disaffected Muslims of Mosul, Azeribijian and Iraq to his banner, swelling his army from 20,000 to nearly triple that number, but most of the new soldiers were ill-equipped, and raw at best. In a battle with Mahmud, the battle hardened

skoutatoi and

kavallaroi would have easily evened the odds despite their numerical inferiority.

Yet even this delicate balance was disturbed when on July 4th, a messenger arrived in Alaeddin’s camp from the Great Seljuk—Sultan Ferdows demanded that Alaeddin kneel before the Great Seljuk Empire as a vassal, and that all his lands and armies fall under the purview of the last remaining Muslim power in the Middle East for the glory of Allah. Alaeddin refused, reasoning that with the Mongols to the Turkish east, Ferdows would be unable to send many men to face the nascent Kingdom. The “King” left his 40,000 partially trained levies to watch Mahmud’s larger army, while he personally lead his 20,000 trained soldiers to face the Turk.

Sultan Ferdows of the Seljuk Empire

Alaeddin’s plan was fatally flawed on two counts, however. First, unbeknownst to the King of Mesopotamia, the Mongols had concluded a peace treaty with the Turk, allowing Ferdows to free up 30,000 men for an attack on Mesopotamia, not the 10,000 or so Alaeddin surmised were present. Secondly, Alaeddin underestimated Ferdows himself. While he was not as gifted a commander as his late brother Faramarz, Ferdows was nonetheless far more competent than his battle record against the West would indicate—he had the unfortunate luck of being Sultan only once the war against Emperor Thomas was apparently lost, which made his defeats at the Emperor’s hand something certain, as opposed to abject failures of command.

For most of the summer the King and Sultan traded diplomatic insults, until finally on October 1st, Ferdows crossed into southern Mesopotamia at the head of 30,000 soldiers. Alaeddin rushed south to intercept, meeting the Turkish Sultan on the field near Basra on the 19th. Ferdows light cavalry pinned Alaeddin’s

thematakoi in place, forcing them to receive a heavy

ghulam charge which broke their ranks. In the ensuing rout, “King” Alaeddin was slain. He’d reigned over his independent Kingdom for less than a year, but the Muslim spirit of resistance that first exposed itself in those fateful months would continue to burn for centuries onward.

When King Alaeddin saw all was lost, he attempted to flee on horseback. When the Seljuk infantry attempted to surround him, legend says his charger managed to leap over the first line of Seljuks before landing directly in front of the second, who mobbed and slew the monarch.

Alaeddin’s movement south left Mahmud facing only levies, a fact that the

Megos Domestikos discovered via spies in mid-August. Immediately, Mahmud pressed south into Mosul, forcing the larger levy Muslim army to battle near Tikrit. The result was never in doubt, and those who Mahmud captured were immediately put to the sword. With 30,000 of their comrades dead, the remaining levies scattered to the four winds, allowing the

Megos Domestikos to re-secure all of northern Iraq by the end of the year. Mahmud’s invasion did not come fast enough to save Basra, Karbala, or areas of Luristan, who eagerly threw their gates open for the men of Ferdows.

On December 26th, outside of Baghdad, the

Megos Domestikos and the Sultan’s armies met. For three days, the two sides stood opposite each other, battlelines arrayed, while the general and the Sultan negotiated. On December 30th, Ferdows agreed to withdraw, so long as the Empire recognized the land’s he’d retaken in perpetuity. This author can only surmise that Ferdows knew his Turkish realm was still desperately weak after over a decade of Mongol and Roman assault—the Seljuks still needed time to take on the Romans in anything more than an opportunistic attack…

==========*==========

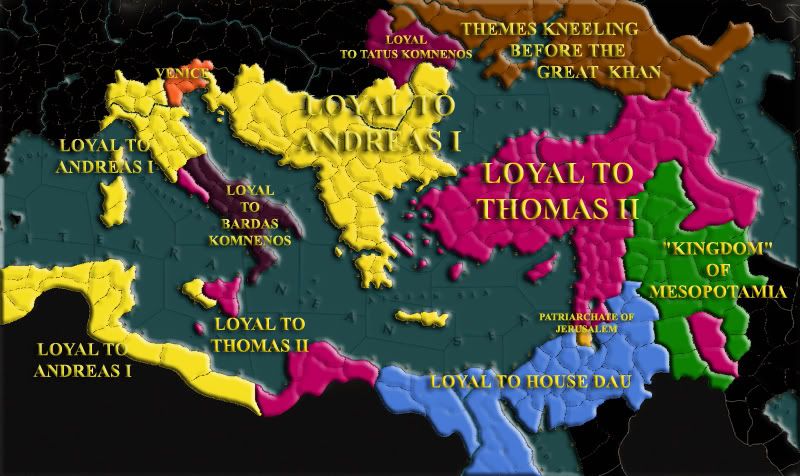

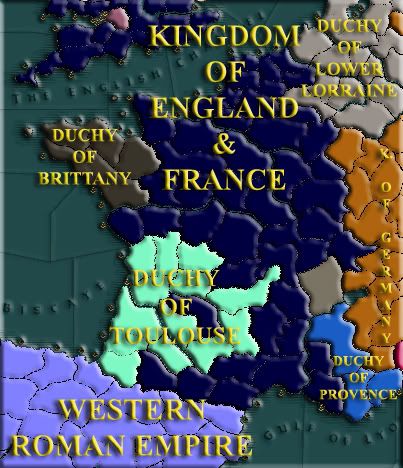

Situation at the end of 1218