Thither to Tsargrad

The Crimson Hills

“He was ruddy as the sun, but all his breast, and down to his feet was the purest white all over, painted with exquisite accuracy. When he was in his prime, before his limbs lost their virility, anyone who cared to look at him closely would surely have likened his head to the sun in its glory, so radiant was it, and his hair to the rays of the sun, while in the rest of his body he would have seen the purest and most translucent crystal.''

- Michael Psellos, Chronographia, describing Constantine IX Monomachos

I finally opened the book that the professor made us buy. He said he was sick and told us to read up on Theodore ourselves. Afterwards some people were saying he was really going to Naxos with a student, but they didn’t say who. But then, they always say things so I don’t believe any. In any case I got reading. The book is surprisingly critical to Theodore, I find. First the author emphasizes his rebellion against Constantine, then talks at length about what he calls an opportunistic attack on Nikephoros, and then mentions that Theodore adopted Byzantine-style law about Imperial succession to gain favour with the Greeks. He quotes Andronikos Philanthropenos, a general and a historian from Theodore’s time, to say that “with the Greeks the Emperor was a Greek, and with the Russians a Russian”. Even I know that phrase. We usually take it to mean wisdom but Mr.Green calls it cynicism.

The book also goes quickly through most of Theodore’s reign, it seems, largely limiting his endless campaigns against his Empire’s western neighbours to dates and a general disapproval at the notion of fighting fellow Europeans. I wanted to learn more so I opened up that book of essays by Russian academics and then shut it again. There’s three papers about the 1136 Pskov campaign alone, dealing with the complex build-up, the relationship with Novgorod and the superiority of Byzantine feudal calvary over Norwegian infantry – “The Decline of the Varangian and the Rise of Eastern Chivalry”, that one’s called. There’s also something about importance of riverways in waging campaigns, and the terrible perception of Western Crusaders in the Empire at the time. Too much detail.

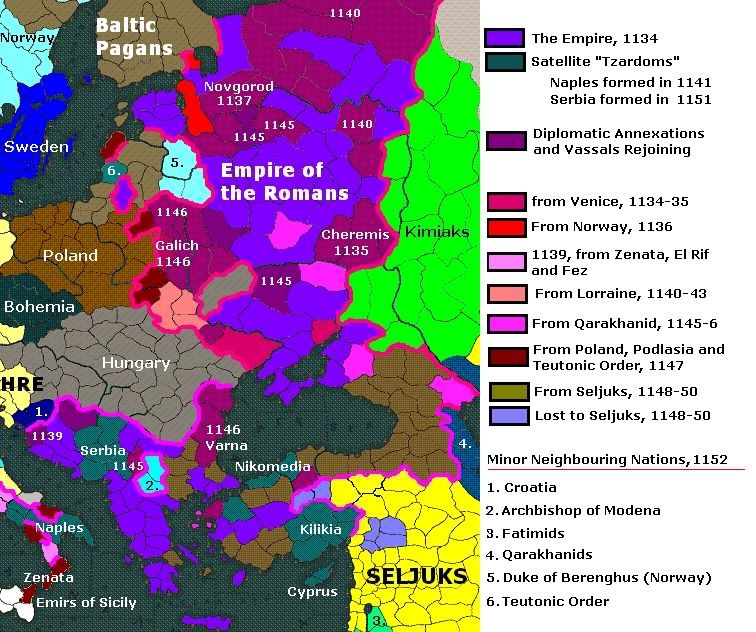

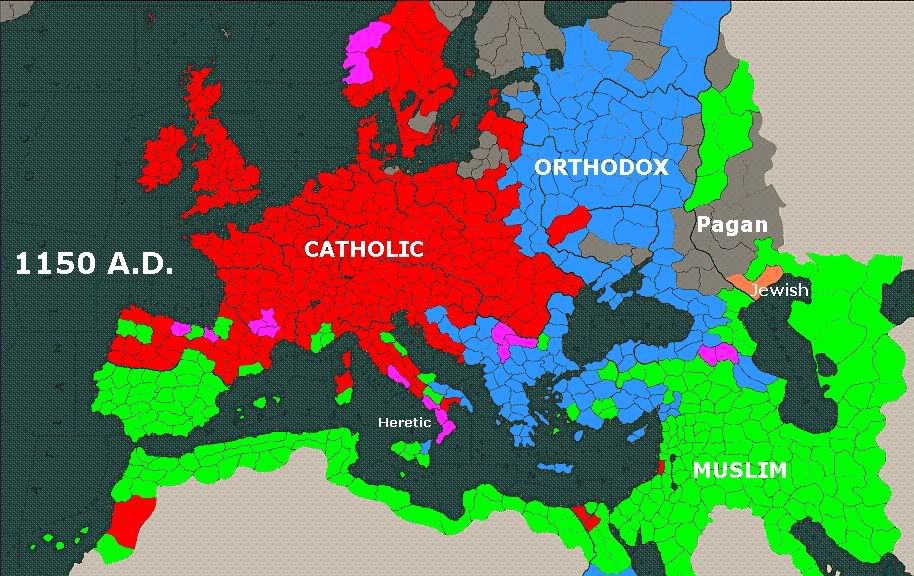

So, essentially, I went back to Green. In 1134, in alliance with Hungary Theodore defeated Venice both in the Ionian and the Black sea, and as soon as the peace was signed allied with Novgorod to beat Norway out of Pskov. Novgorod’s republic then joined the Empire in the broader sense, a sort of permanent military alliance and a promise to recognize the Emperor as the nominal sovereign. After that he fought the Moslems in Italy, setting up an Orthodox Neapolitan kingdom by 1141. In 1140 he finally added Kiev back to Rus by driving out the Germans, whose shaky occupation was unable to withstand a popular uprising backed by Byzantine troops. The weak Qarakhanid state was his next target, and after that an alliance of Poland, the Teutonic Knights, and the rebellious vassal Podlasia, lost by his predecessor Heraklios. In 1146, seeing the Empire’s seeming invincibility, the proud Cherven dynasty in Varna and the Izyaslavich princes in Galich finally acknowledged Theodore as their overlord. Although he never called upon either to provide troops, it boosted his prestige greatly. He must have felt like nothing could go wrong at that point.

The next war is what Green focuses on, and the essay book has way too many to even start reading through them all. Interestingly, Green begins his “Great Seljuk War” chapter by stating that in his opinion Russia’s relentless wars against the Turks in the 19th century were directly influenced by the accounts of Theodore and his successors’ campaigns; in fact, the historical undertones, he claims, let the Russian Emperors pursue wars they’d have never been able to get away with otherwise. I should bring this up with Demetre when we go for lunch. He invited me and I agreed again. I wonder why I keep doing that.

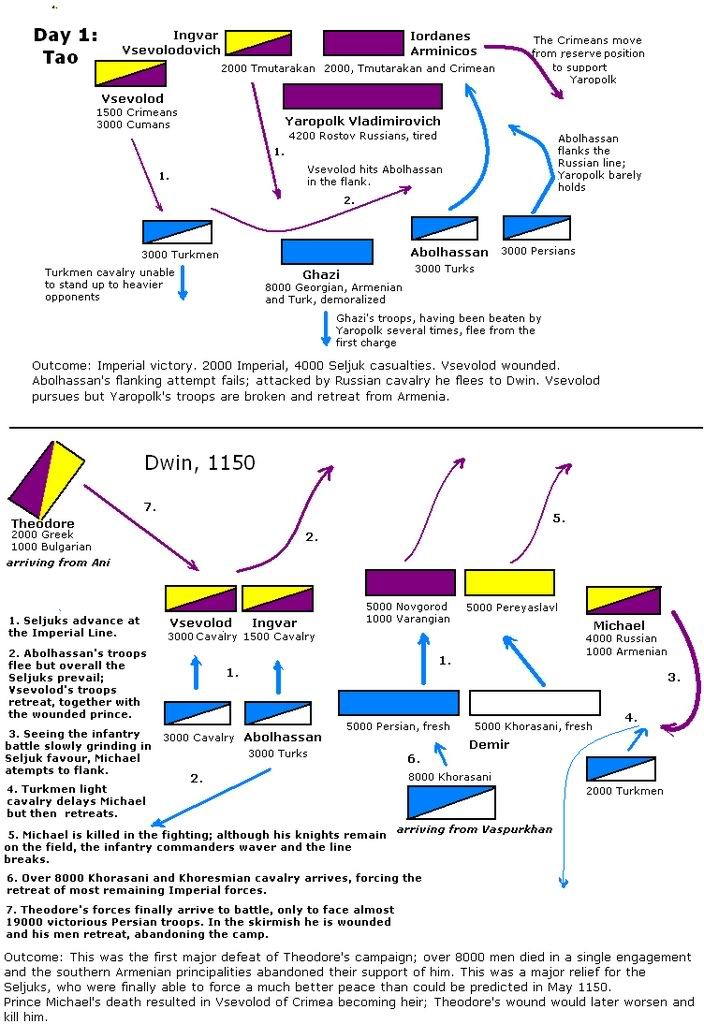

So in 1148, after a long period of solidification and small expansion, the Empire declared war on the strongest of their neighbours – the Seljuks. By all accounts, the Seljuks were caught unawares due to internal troubles, else they’d not have done as badly as they did. They lost mainland Greece to Theodore’s Constantinople-based army in less than a year, and the Aegean islands by the beginning of the next. Vsevolod of Crimea and Andronikos Philanthropenos, the Megas Strategos, occupied the maritime provinces in northern Anatolia one by one, while Yaropolk of Rostov and Ingvar of Tmutarakan pushed slowly and often bloodily, with the help of local Georgian and Armenian Christians, through the Caucasus. From Novgorod, Smolensk and Pereyaslavl, Michael, the other son and the heir, lead a large army to the south to support the Crimean and Tmutarakan troops. The Seljuks finally managed to muster their realm only in the middle of 1149, and a lot of their force was spent attacking Cappadocia and Syria, all the while the local Beys and Emirs were thrown out of the Caucasus. Abolhassan, the Seljuk Sultan, finally managed to organize a single large army and marched towards the Caucasus; another army, much larger and summoned from every corner of the Seljuks’ Persian and Kwarazmian possessions, was to join him as soon as they could.

By summer of 1150 it became clear that Armenia would be the place of final battle of this war. All functional Imperial and Seljuk forces headed towards the same general area. Neither side was willing to engage and spent most of the summer maneuvering to win supply base, local support, a better position, and most importantly, time for reinforcements to arrive. As September rolled on, it became clear that the armies would soon run out of food and the harvest may well be lost if not gathered. Abolhassan decided to engage Vsevolod and Ingvar outside a small town in Eastern Ani. His defeat was swift, and he fled to Dwin, where the Persians were facing off against Michael’s Russian forces. The battle that followed is legendary; the Russians have written a dozen laments about the dead at Dwin; the Greeks a hundred books on strategy based on what happened there. The Empire lost fully a fifth of their total fighting force, a crown prince, and Novgorod’s generous contribution to the battlefield, something they could never count on since. Both the Emperor and his surviving son were heavily wounded.

The Empire lost a chance at total victory, and had to give up Syria and Cappadocia in return for Thessaly, Macedonia, Antaliya and the Caucasus. What the Empire gained instead was glory. For the first time in history, every orthodox nation in Europe stood united under one banner – Rus, Greek, Bulgar, Serb, Albanian, Syrian, Armenian, Georgian, Alan, Cuman and Goth, and did extremely well. The Turk Sultan, by contrast, lost the respect of his men on that battlefield, and subsequently his crown and his life. His cousin, the Khorasani Demir, became Sultan, and shifted the centre of Seljuk power east into Persia. Perhaps this was the reason why the Empire and the Crusaders could pursue such a successful policy in the Levant thereafter; perhaps also, because of Persia’s strengthening, the Seljuks were able to stop the Mongol invasion when it came.

This was Theodore the Great’s last war. He died two years later of the complications arising from the wounds sustained at Dwin. His son Vsevolod was chosen Emperor over the other prominent vassals - Andrew of Smolenk (another son), Boris Cherven of Varna, Ingvar Knytling of Tmutarakan and Theodoros Elegemites, who in the beginning of the war was a mercenary general from Cyprus and Lord of most of Caria and Lycia by the end of it.

Although he wasn’t his father’s favourite son, Vsevolod was to prove a worthy successor, using the strength and prestige accumulated by the Empire under Theodore to influence affairs around Europe as he saw fit.