A Biography of Great Men – A History of Britain: 1836-1935 [HoD 3.03]

- Thread starter DensleyBlair

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The general's profligate means of waging war would later serve to lower his reputation amongst historians, and was highlighted as one of the major manifestations of mismanagement during the war.

Now that is a gross understatement.

Unfortunately, due to their pathetic conduct of the war - and not to mention the fact that they got Britain involved in the damned conflict in first place - it appears that the Liberals (and I say Liberal as one suspects the days of the Whigs and Peelites as separate political forces to be numbered) will be rewarded with another thumping majority; this one considerably less deserved than the last. If any good may come from this outcome, may it take the form of a gratuitous Tory row culminating in a glorious political coup led by the Tory Member for Buckinghamshire.

We, the people... I mean readers, demand a map of the new Europe!

I shall have one up for you immediately after my exams have finished.

Thank you kindly for your comment, as ever. Good to hear you're still reading along!

hmy: How?

First of all, a very warm welcome to the thread – and indeed, to AARland-at-large, Sir Lancealot! I trust you'll enjoy your stay in both entities.

As for your question, I honestly have no clue. I can just assume that the British army's technology was attrocious compared to that of their contextual counterparts – which would be largely in-keeping with history. Inevitably, a war involving Britain in the mid-19th century will be a hideously inefficient mess of a thing.

Now that is a gross understatement.

Truly, Jellicoe was the Haig of his time.

Unfortunately, due to their pathetic conduct of the war - and not to mention the fact that they got Britain involved in the damned conflict in first place - it appears that the Liberals (and I say Liberal as one suspects the days of the Whigs and Peelites as separate political forces to be numbered) will be rewarded with another thumping majority; this one considerably less deserved than the last. If any good may come from this outcome, may it take the form of a gratuitous Tory row culminating in a glorious political coup led by the Tory Member for Buckinghamshire.

Do remember that, in our timeline, the Whiggish dominance (for, saving the first part of Gladstone's first ministry when the Radicals were actually able to get stuff done and force their way into prominence, it was a Whiggish dominance) lasted for nearly thirty years from 1846. This timeline, owing to the fact that in Victoria, as in life, Britain has a naturally liberal electorate during the period, will be little different for the most part – and God knows making it different has been a massive struggle. One can always find solace, however, in the fact that, whenever the liberals choose to squabble amongst themselves, the Derby-Dizzy alliance stands ready to assume government.

Thank you very much to those of you who have commented thus far. Your thoughts are always greatly appreciated, and it look forward to hearing any more that people may offer over the next few days. As hinted above, I embark as of tomorrow morning upon my GCSE mock exams, meaning that my time for AAR matters may be limited until some point during the middle of next week. With that in mind, I'll probably kick off the election cycle the weekend after next.

Until then!

Now that is a gross understatement.

Unfortunately, due to their pathetic conduct of the war - and not to mention the fact that they got Britain involved in the damned conflict in first place - it appears that the Liberals (and I say Liberal as one suspects the days of the Whigs and Peelites as separate political forces to be numbered) will be rewarded with another thumping majority; this one considerably less deserved than the last. If any good may come from this outcome, may it take the form of a gratuitous Tory row culminating in a glorious political coup led by the Tory Member for Buckinghamshire.

Do we realy want Lord Derby as Prime Minister? I say let the Liberals return, for they do have men able to understand what the country needs of them, they are not peasents without a leader, like the Tories, as we have seen in the unholy ministry, they are men who have proven their worth and it would be a waste if Lord Palmerston did not return to Number Ten.

Ah yes, GCSE's. An excellent way to stop education three years before the next educational endeavor begins. I obviously blame Labour.

Do we realy want Lord Derby as Prime Minister? I say let the Liberals return, for they do have men able to understand what the country needs of them, they are not peasents without a leader, like the Tories, as we have seen in the unholy ministry, they are men who have proven their worth and it would be a waste if Lord Palmerston did not return to Number Ten.

Well obviously if Dizzy leads a coup then Lord Derby wouldn't be Prime Minister.

I think it's fair to say that they have proven their worth, and have been found to be wanting.

Ah yes, GCSE's. An excellent way to stop education three years before the next educational endeavor begins. I obviously blame Labour.

Introduced in 1986? An interesting theory, no doubt...

Introduced in 1986? An interesting theory, no doubt...

Well if Foot hadn't been so damned unelectable...

GCSEs? God I forget how young you are due to the level of your writing.

Khaki election! Or rather a Scarlet election? Pam is playing everyone like a fiddle, as he is want to do.

I do wonder about everyone's attitude to Poland, and Poland's attitude to everyone else for that matter, will be. Russia was keen to keep the Poles IOTL but they probably have little interest in retaking it now. A small crumb of comfort will be a far more defensable frontier and no Vietnam-style rallying cry for Russian liberals. Its notable that the Bonapartists were always Poland's biggest ally in the 19th century, with the new state being a creature of Les Anglo-Saxons (in French eyes) will Warsaw have anyone willing to go to bat for them? The Germans might but only as long as Poland stays focused on Russia, Silesia and Austrian Galicia are very much the elephant in the room. Could be a place were France steps in later on. Pam was very keen on defending national self-determination but I could see him as easily ignoring Warsaw if it suited him. Disreali would have an interesting relationship with Poland, given the nation's historic inclinations towards their Jewish population.

And yes a map.

Khaki election! Or rather a Scarlet election? Pam is playing everyone like a fiddle, as he is want to do.

I do wonder about everyone's attitude to Poland, and Poland's attitude to everyone else for that matter, will be. Russia was keen to keep the Poles IOTL but they probably have little interest in retaking it now. A small crumb of comfort will be a far more defensable frontier and no Vietnam-style rallying cry for Russian liberals. Its notable that the Bonapartists were always Poland's biggest ally in the 19th century, with the new state being a creature of Les Anglo-Saxons (in French eyes) will Warsaw have anyone willing to go to bat for them? The Germans might but only as long as Poland stays focused on Russia, Silesia and Austrian Galicia are very much the elephant in the room. Could be a place were France steps in later on. Pam was very keen on defending national self-determination but I could see him as easily ignoring Warsaw if it suited him. Disreali would have an interesting relationship with Poland, given the nation's historic inclinations towards their Jewish population.

And yes a map.

Well if Foot hadn't been so damned unelectable...

I feel compelled to write a joke about Labour putting their foot in it...

You British and your inscrutable politics confuse me.

Believe me, they confuse most of us as well.

Khaki election! Or rather a Scarlet election? Pam is playing everyone like a fiddle, as he is want to do.

Or a Thin Red Line Election, even. Pam certainly came out smelling of roses, that's for sure. He still has to face the people, though.

I do wonder about everyone's attitude to Poland, and Poland's attitude to everyone else for that matter, will be. Russia was keen to keep the Poles IOTL but they probably have little interest in retaking it now. A small crumb of comfort will be a far more defensable frontier and no Vietnam-style rallying cry for Russian liberals. Its notable that the Bonapartists were always Poland's biggest ally in the 19th century, with the new state being a creature of Les Anglo-Saxons (in French eyes) will Warsaw have anyone willing to go to bat for them? The Germans might but only as long as Poland stays focused on Russia, Silesia and Austrian Galicia are very much the elephant in the room. Could be a place were France steps in later on. Pam was very keen on defending national self-determination but I could see him as easily ignoring Warsaw if it suited him. Disreali would have an interesting relationship with Poland, given the nation's historic inclinations towards their Jewish population.

Russia's Polish ambitions have now largely been curtailed – especially now that Alexander has acceded and brought with him a far more eirenic foreign policy outlook. Nevertheless, Russia will always be Russia, and so you can expect some more diplomatic meddling in the future.

As for Poland specifically, France aren't necessarily hostile to them, and indeed Napoleon is likely friendly to their causes – though he is even more friendly to the idea of being accepted by the existing European order, hence helping the Tsar. I will say now that the area actually remains pretty quiet for the most part up until my current point in the game – though that's not to say the great powers completely ignore their new buffer against Russia.

Dizzy's foreign policy, while generally successful, was never one for organised planning – so I imagine he'd take whatever view of the Poles the situation desires.

And yes a map.

Interfrastically.

I may be able to start the election cycle off this weekend – though may is the key word there. My first priority after exams is naturally providing a decent map of Europe, so that may take some time, but the platforms shouldn't be too hard to come up with after that.

Until then!

This would not be - by Dr. Johnson's definition - what I'd call interfrastically.

Oh, I finished the map about a week ago. I'm just waiting until the next update (which has been started) to post it. Hopefully, I'll have it for you before the weekend's close.

In other news, the ACAs are back! If you are yet to do so, why not go and vote at some point in the near future? Various year-end awards can also be found within the AARland main forum.

In the meantime, I'm hoping to have the parties and election background out in the next few days.

Oh, I finished the map about a week ago. I'm just waiting until the next update (which has been started) to post it. Hopefully, I'll have it for you before the weekend's close.

In other news, the ACAs are back! If you are yet to do so, why not go and vote at some point in the near future? Various year-end awards can also be found within the AARland main forum.

In the meantime, I'm hoping to have the parties and election background out in the next few days.

While that is great news, my point still stands. I'll forgive you.

And yes make your voice be heard at the ACAs people. Or as my good friend Mr. Mitchell would say:

Can we have a map of Europe ? I am interested how it is looking now.

It really is not very different to the game's start. The only thing to have changed is the emergence of Poland. Nevertheless, as noted above, a map is ready and will be up with the next update.

Welcome to the thread, by the way!

While that is great news, my point still stands. I'll forgive you.

Well thank God for that.

And yes make your voice be heard at the ACAs people. Or as my good friend Mr. Mitchell would say:

Likely the one and only time I will be happy endorsing Mr. Mitchell's ideas.

Glad to see a measured peace. And hopefully brave Poland can survive! I've played so many games where I've liberated them, only to see them steamrollered a few years later when I decide to fully leave them to their own devices.

1857 General Election: The Parties

Background

The election of 1857 was notably for its many unique characteristics when compared with others of the period. First, of course, it was the result of a government felled, eventually, by a war in which Britain had emerged victorious – again, eventually. This naturally meant also that, whilst having to appeal to the people for a renewed mandate having been so challenged by the forces of opposition, Palmerston's ministry was generally popular – "popular" not being a word used often to describe a ministry going into early elections. There was also the nature in which Parliament had been dissolved and in which elections had been called. Whilst all appeals to the country could be seen as such to some degree, more than any other election of the period can 1857 be seen ultimately as a referendum on the sitting ministry's conduct. Although in theory the fresh elections meant a chance for the parties and other various groupings in Westminster to bolster their seat totals, this was not the overriding concern on this occasion. Instead, a single issue dominated proceedings; namely, Palmerston himself. In voting for the continuation of his coalition of Whigs and other members of the anti-Derby bloc, one was in effect condoning the premier's waging of the war (and also, to an extent, that of his predecessor Lord Lansdowne.) In voting for the Conservatives in opposition, one was condemning Palmerston's behaviour as reckless and his prosecution of the war as one long chain of incidents of gross misadministration.

Despite this relative security going into the election, the sitting ministry was by no means wholly secure. The Masovian War had created and, in some cases, worsened various internal disputes that inevitably arise during coalitions. The Radicals, for example, were dead set against the war as profligate and morally wrong, with John Bright privately one of its most vociferous opponents. (Publicly, he was barred from coming out against the war by his cabinet position.) This was a view also taken by Gladstone at the exchequer, the chancellor ever against any form of unnecessary spending. His fellow Peelites were more reserved, though some privately harboured grievances with Palmerston's more reckless diplomatic adventures. Only the Whigs were mostly unanimous in their support for the conflict, led and encouraged by Palmerston's anti-Russian sentiment (as well as that of the people) and the triumph negotiated in Berlin.

In contrast to the patchwork-like government, Derby's Conservatives had long since overcome their internal struggles to emerge as a coherent grouping in Parliament. Likely helped by the absence of real talent from his ranks, something that meant clashes of egos or personalities were rare amongst the opposition front bench, Derby's Conservatives required little driving[1]. Unified also by a relatively lengthy spell in opposition, the Conservatives were in a far better place going into the election of 1857 than they had been six years prior. Unity alone, however, would not win them the election – a fact of which Derby was keenly aware, knowing full well the potency of the arachnid abilities of the premier to keep the trust of the British public on his side. For all of his good work in restoring the Conservative Party to a position of credibility after the disastrous Who? Who? Ministry that had cost them victory so dearly in 1851, Palmerston's ubiquitous appeal and his pandering to the beating heart of the British nation would be very hard to overcome. Any Conservative government after the election would also be faced with the challenge of living up to the brio of the previous government with its own more modest collection of talents. Derby, whilst generally regarded as a fine orator and undoubtedly a seasoned statesman, was not of the calibre of opponents such as Russell, the energetic reformer and symbol of Whiggish spirit, and Palmerston, arguably the last true Canningite[2], whose ability to dominate a cabinet of very strong personalities was not to be undervalued. By comparison, aside from Lord Derby the Tories could call upon only Benjamin Disraeli, the beguiling, enigmatic and widely distrusted member of the opposition front bench, as a man of real talent.

In 1857 it appeared that the Treaty of Berlin would usher in a new period of peace and stability in Europe, during which Britain would be free to exercise her dominance over the continent unchallenged.

Arguably, with Britain at her strongest, the need for a strong government was not as potent as it had been during the war. Unchallenged even on the continent in terms of her diplomatic power, even with Derby's uninspiring foreign secretary Lord Malmesbury at the helm, it would be a challenge for a government to scupper her prime position. Palmerston's gung ho style of diplomacy meanwhile, which as we have already seen was not to the tastes of the vast majority of Europe's diplomatists, certainly was effective at keeping Britain on top of the pile, yet it was equally abrasive. Much of the opposition, and a few dissenting voices within the government, were worried that for him to be allowed to continue unrestrained would be to condemn Britain to involvement in a second continent-wide conflict sooner rather than later. Definitely, this was amongst Derby's concerns as he and his more placid party sought to upset Palmerston's unassailable rise. The British public, however, were much more on the side of the premier and his prestige-laden policies. The fact that the ensuing political battle would be hard-fought was the only really certainty.

The Manifestos

Whig Party

Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston. Prime minister and leader of the Whig Party since 1854.

Leader and Prospective Prime Minister: Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston (leader since 1854)

Political Ideology: Whiggism; namely a heady mix of classical, moderate and radical liberalism promulgated by the landowning aristocracy

Position on the Political Spectrum: Centre to hard-left

Party Colours: Buff, orange and light blue were traditionally used together. Some candidates preferred various shades of yellow.

Economic Policy: The Whigs were most happy when the government intervened as little as often in the affairs of the markets, with some more radical members sometimes going out of their way to oppose the reforms of the social Tories such as Shaftesbury to this end. The economy was therefore left to its own devices, with the Whigs typifying the 19th century approach to government in terms of minimal involvement. Freedom of trade was also a key tenet of Whiggism, and so respected at all times. Although Palmerston was by no means as ardent a Whig as some of his ministerial colleagues, he had no desire to amend this, and so the spirit of 1846 and the repeal of the Corn Laws was continued well into the next decade.

Foreign Policy: Palmerston's style of foreign diplomacy has long been debated, discussed, declaimed and defiled. To his supporters, Palmerston embodied the ultimate Englishman – possibly even the ultimate Briton – willing to go to any lengths to ensure that British interests were maintained wherever they may come under threat across the globe. To his detractors, Palmerston was a charlatan, a scoundrel and a threat to the delicate balance of power in Europe, whose bellicose attitude to diplomacy would set Britain on an inevitable path to war. Nevertheless, this was the policy taken by the Whigs during Palmerston's tenure. The prime minister, it could not be doubted, was the dominant force within the party, having rather unexpectedly brushed aside both the sage statesman Lansdowne and the perpetual heir apparent to the Whiggish legacy Lord John Russell to usurp control of the party. And he showed no signs of abdicating this position. Neither did the party – and, more importantly, the people – wish for him to do so. Ultimately, Palmerston's foreign policy was immensely popular, and would be the main obstacle to the Tories' hopes of winning a majority.

Defence Policy: Palmerston, constantly alive the threats from across the channel – imagined and otherwise – was always sympathetic to the matter of defence, being in favour both of the improvement of defences in coastal regions (so as to protect against the French) and the expansion of the military where necessary. Mainly, his concern lay with the navy, believing that Britain would be far better served by its wooden wall than by its fighting men, as had been effectively demonstrated during the Masovian War. Therefore, the Whigs went into the 1857 elections in the unusual position of being in support of military – particularly naval – expansion, a stance usually reserved for the Conservative opposition. So as to ensure the protection of British interests abroad as well as at home, colonial garrisons would also continue to be supported.

Stance on Reform: Under first Lansdowne and then Palmerston, the Whigs had lost a great deal of the reformist spirit that had been present under the leadership of Russell. Whilst Lansdowne lacked the drive or incentive to support reform to any particularly sincere degree, Palmerston was decidedly against the historical Whiggish issue: the expansion of the franchise. Viewing such expansion as unsavoury on grounds of the working classes being far too ill-educated to vote, amongst other concerns, Palmerston effectively silenced any talk of such reforms in favour of more moderate policies and reforms to institutions such as the penal system. In this regard, he was opposed by Russell, who was growing ever more convinced of the inadequacy of the Great Reform Act. Largely, however, Russell's worries went unshared by his colleagues and by the electorate, who were happy with system as it existed. Reform was therefore not a large issue for the party in the late 1850s. Social reform, however, was generally supported as and when it was introduced to the Commons, provided it did not interfere too greatly with the party's sacrosanct policies of economic liberalism.

Stance on the War: Evidently, as its main orchestrators, the Whigs were generally unconcerned by the conduct of the war, more concerned by its successful conclusion and the resulting shifts within the European concert. Some dissenting backbenchers of a more radical bent were less convinced of Palmerston's position, though these voices were decidedly within the minority.

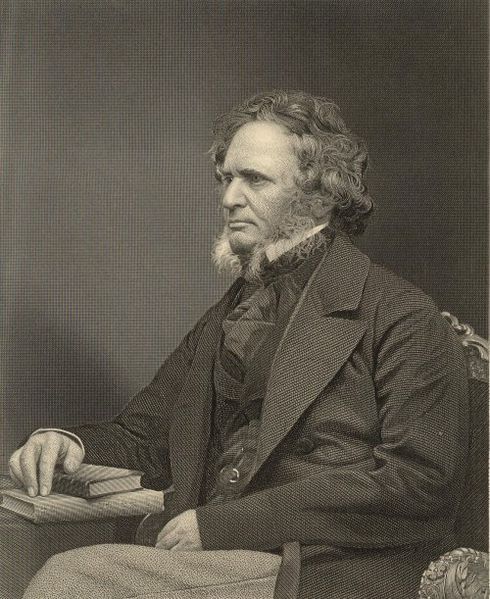

Conservative Party

Edward Smith-Stanley, 14th Earl of Derby. Leader of the Conservatives and formerly prime minister (1843-1846; 1851)

Leader and Prospective Prime Minister: Edward Smith-Stanley, 14th Earl of Derby (leader since 1851)

Political Ideology: Conservatism (of varying intensities,) Toryism, Social Toryism

Position on the Political Spectrum: Centre to hard-right

Party Colours: Dark blue was traditional, though purples and other shades of blue were used by some candidates

Economic Policy: Having seen their fiercely-guarded policy of protectionism fall flat onto its sword on multiple occasions throughout the late 1840s (the "Hungry Forties") and early 1850s, free trade became part of the consensus as the 19th century reached its midpoint. In the aftermath of the party's failure at the 1851 election, Derby quietly shifted the focus from protectionism onto a more agreeable situation whereby trade was not brought up within the party. This regression to a de facto policy of free trade largely came about as a result of Disraeli's campaigning, Disraeli never having been a protectionist, and having also noted that a commitment to anything other than free trade would see the party unable to win a majority for years to come. Whilst the party still supported a greater level of intervention than the Whigs, notably through the reforms of people like Shaftesbury, there was by 1857 a much greater sense of concord between the two parties as far as economics were concerned.

Foreign Policy: For Derby's Conservatives, foreign policy was something more in need of inaction than direct action. The unremarkable Lord Malmesbury was not a diplomat of any great calibre, and his idea of foreign policy certainly rested more on reacting to events as best as one could than actually trying to influence them. In many aspects, the Tories were the complete opposite of the Palmerstonian Whigs in this regard, and were largely more desirous of preserving Britain's stature than heightening it. The empire was largely supported, however.

Defence Policy: Following the horrendous instances of mismanagement during the Masovian War, or at the very least those perceived by the Tories, it was abundantly clear to the party that something needed to be changed. Largely, however, this change rested mainly in refraining from embroiling Britain in future conflicts rather than radically shaking up the military. Similarly, the Conservatives held no pretensions of Britain being a great military power on the continent. Whilst her navy would naturally need to remain as the greatest in the world, there was little point in expanding the army in Europe when European wars were to be avoided. The colonies, however, were a different matter; expansion would be pursued where necessary, especially in India where tensions between the various peoples in the region had begun to heighten in recent years.

Stance on Reform: The Conservative Party in the late 1850s remained wholly against any ideas of the expansion of the franchise. Quite rightly, the vast majority of the party dismissed the idea of expansion as a nonsense, desired neither by the working classes nor by the as-yet-enfranchised middle classes. Agitation for reform was minuscule, with much of the impetus within Parliament coming from Bright's relatively small group of Radicals, despite everything largely distrusted by the traditional establishment, and a few members of the Whig Party. Therefore, reform was not a matter contemplated by the Tories at the time. It can be said, however, that such initiatives as those conducted by Lord Shaftesbury would generally be supported were they to come up.

Stance on the War: To the Conservative Party, the Masovian War embodied all that was undesirable about the Whigs under Lord Palmerston. It was a war that had been largely caused by a Whiggish administration, albeit one to have since fallen, that had proceeded to prosecute it with a distinct lack of vigour and expedition. Lansdowne had proved dithering and ineffective as a war leader, having gratefully resigned in 1854 when the added strain of the war began to affect his health. With Palmerston's accession to the premiership, however, the lethargy to which the Conservatives had been so opposed was replaced by an almost inconsiderate speed that had resulted in countless incidents of mis-administration by the general staff. The fact that the war had been win after a gruelling four year period was irrelevant; the sitting ministry had to be made an example of to prove that neither profligacy nor reservation would be tolerated in too great a measure.

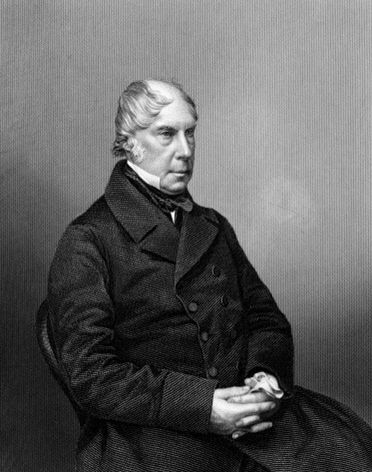

Peelites

Veteran statesman and Peelite leader George Hamilton-Gordon, 4th Earl of Aberdeen. Previously prime minister (1850-1851).

Leader and Prospective Prime Minister: George Hamilton-Gordon, 4th Earl of Aberdeen (since 1851)

Political Ideology: Moderate Conservatism, Classical Liberalism, Liberal Conservatism

Position on the Political Spectrum: Centre to centre-right

Party Colours: Light blue and sea green were most commonly used

Economic Policy: Being the issue over which the party saw fit to break with the Stanleyite Conservatives in 1851, by 1857 the Peelites still remained committed to the idea of free trade, which had first been adopted by their late former leader twenty years prior. Further, under Gladstone's chancellorship the party had become one dedicated to keeping government expenditure low, with Gladstone convinced that it was a government's duty to its people to ensure that they were taxed as little as possible. Some more conservative members of the faction likely would not have shared this view, supporting the work of social reformers whose projects placed further financial burdens upon the people, though Gladstone's position as the group's chief economist meant that these views were often overshadowed in his favour.

Foreign Policy: Led by the seasoned diplomat Lord Aberdeen, the Peelites' foreign policy breasted upon the idea of cooperation with the other European powers as opposed to antagonising them, and was generally rooted in the ideas formed during the post-Napoleonic peace in Europe, during which war diplomacy was seldom required. Aberdeen especially was a great Francophile, and so somewhat dismayed by the recent deterioration of relations between the two countries – Britain and France – having previously spent most of the 1840s improving them. Despite this, most of the rank and file Peelites shared the endemic mistrust of the French omnipresent within Westminster, and the Emperor Napoleon was certainly not admired. In Gladstone's eyes, the cost of colonial wars and possessions was a great deterrent, though most Peelites – being more in tune with the moderate wing of the Tory Party – were more sympathetic to the idea of empire.

Defence Policy: To the Gladstonian Peelites, military expansion was anathema. Armies being a substantial drain on a nation's finances, supporting a standing force in times of peace would be in contravention to the idea that government spending should be as low as possible so as to tax the people as little as possible. Gladstone also being generally against war, both for economic and less practical reasons, maintaining an army would make little sense when it was never to be used. Therefore, no expansion would be allowed under his budget. Whilst not as able to influence matters of spending, and therefore defence, Peelites with a greater sympathy towards Abderdeen (in other words, the right wing of the party) held a more neutral stance on defence, not being overtly bellicose, though neither wishing for such radical measures as supported by Gladstone.

Stance on Reform: The Peelites, sandwiched between the more moderate, Canningite wing of the Whig Party and Lord Derby's Conservatives, were not generally in favour of drastic measures such as reform to the franchise. Sir Robert Peel's Tamworth Manifesto declaring the Great Reform Act of 1832 to be "a final and irrevocable settlement of a great constitutional question", few of his heirs disagreed. Even where Peelite members may not have been in complete accordance with their late namesake, plenty expressed other concerns about the idea of franchise expansion, with Gladstone in particular opposed to expansion on the grounds that many working people displayed no interest in politics, and so were not sufficiently informed as to be able to vote. Nevertheless, the Peelites generally supported the social Toryism of Lord Shaftesbury, in favour of similar redressals of dangers within industry.

Stance on the War: Whilst nominally in favour of the war owing to their positions within the cabinet and the government-at-large, many Peelites – especially those of a Gladstonian leaning – remained highly sceptical of the inefficiency of the war. Further still, some held doubts over the prudence of Lord Palmerston's foreign policy, of which the Masovian War could be said to be a direct manifestation, and so held qualms about the conflict on the grounds that to support it would be to endorse Palmerston's recklessness. Officially, however, the party remained supporters of the government, the motion regarding the war essentially a vote of confidence in Palmerston's ministry, likely due to the resignation of Lansdowne, which solved for many the problem of responsibility for the mishandling of the war.

Irish Repeal Party

Parliamentary leader of the Repeal Movement William Smith O'Brien, who by 1857 had been the party leader for a decade.

Leader and Prospective Prime Minister: William Smith O'Brien (leader since 1847)

Political Ideology: Irish Independence, Classical Liberalism, Radicalism

Position on the Political Spectrum: Centre-left to hard-left

Party Colours: Various shades of green. Some candidates chose blue and good as the colours of Ireland's coat of arms. Members associated with the Young Ireland movement sometimes used orange, though the Protestant and Orangist connotations were often avoided, and so more traditional colours were more prevalent

Economic Policy: Its focus mostly taken up by the idea of repeal (of the Acts of Union,) the Repealers' economic policy generally fell in line with that of the Whigs and the Radicals, conforming with the general mid-century consensus. A fundamentally liberal party, the freedom of both trade and the markets were respected, with the former an especially contentious issue in the past owing to the existence of the Corn Laws and their crippling of the Irish economy. With economic fortunes improving during the 1850s, this had become less of an issue, though the party remained against any sort of special economic status given to Ireland by Westminster, pride having meant that Peel's interventionist measures were not generally well received by Ireland's representatives in the Commons. Ago their hangover from the end of the previous decade was the the party's opposition to a perceived exploitation of Irish industry and resources by Westminster, with Smith O'Brien and company firmly in favour of Irish produce being used by the Irish people, as opposed to being sold on the world markets first.

Foreign Policy: The Irish party generally remained aloof of foreign policy debates, preferring instead to focus on those directly relevant to Ireland. Therefore, whilst Palmerston's policies were met with a general unease by some, he was never outright opposed by the Irish – nominally, his coalition partners.

Defence Policy: The Repealers were not ones to busy themselves with the defence of the United Kingdom – the U.K. being an institution that was, in theory, opposed by the party, it must be remembered. Nevertheless, the Irish party were often in agreement with their frequent allies the Whigs, though the idea of British troops being stationed in and coming from Ireland no doubt rankled. The party's policy on defence can therefore most accurately be surmised as a neutral one.

Stance on Reform: The most obvious reform pursued by the Repealers, if it could indeed be called a reform, was the repeal of the Act of Union biding the Irish with the rest of Britain. Having been in place for over fifty years by 1857, and with levels of Irish support in the Commons largely unwavering, the act's repeal seemed ever more unlikely. Under Daniel O'Connell in the 1820s and '30s, the Irish party had seemingly found a niche within Westminster as the Whigs' biting partner from across the Irish Sea, vociferous in their support for issues such as Catholic Emancipation and even electoral reform. Yet under Smith O'Brien and company, the movement had lost direction. Whilst nominally still desirous of the Act of Union's repeal, during the party's near three decades of existence little progress had been made, and so the party had become largely Repealers only in name. By the 1850s, the party was more one to represent Irish interests in Westminster than to advocate Ireland's removal from the union.

Stance on the War: Nominally under the aegis of the Whigs, the Irish party nonetheless remained largely quiet on the issue of the war, preferring instead to concentrate on issues more relevant to the Irish people.

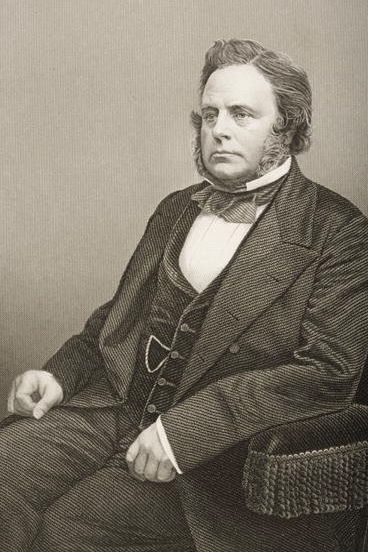

Radical Party

John Bright, leader and doyen of the Radical Party.

Leader and Prospective Prime Minister: John Bright (leader since 1847)

Political Ideology: Radicalism, Classical Liberalism

Position on the Political Spectrum: Centre-left to hard-left

Party Colours: Various shades of orange and yellow, with the occasional use of gold

Economic Policy: John Bright, along with his lieutenant Richard Cobden, had been one of the most vocal supporters of the repeal of the Corn Laws, having campaigned for such for many years prior to their eventual repeal. The defunct Anti-Corn-Law League, having been formed by Bright and Cobden in 1838, was in many ways the precursor to the Radical Party, and so it's economic values were inherited. Classical liberal policies were held as gospel and unchallenged within the party, with both government and government spending to be kept to a minimum.

Foreign Policy: The Radicals views on foreign policy were similarly influenced by matters of economy, with the expense of wars and colonies a far greater factor than the benefits that colonies may bring. To this end, expansion of the Empire was usually met with either distaste or ambivalence by the Radicals, with Bright especially of a pacifistic leaning that was informed by his faith, being a prominent Quaker. The Radicals were also distrustful of Palmerston's excessive antagonism of other powers, and preferred instead to maintain a more eirenic relationship with the rest of Europe, though diplomacy was never high on their agenda.

Defence Policy: Pacifism or otherwise some degree of anti-militarism was a fundamental tenet of the vast majority of the Radical Party, owing largely to the fact that the party drew much of its membership from Quaker societies and other such bodies. Aside from this religious conviction, the party's dislike of war also stemmed from an economic base; namely, in agreement with Gladstone, that war is merely a drain on a nation's finances. The Radical Party had a strong tradition of opposing wars within Parliament, with some Radical members of the Whiggish ministry to have formed in the wake of the 1851 election even going as far as crossing the floor at the outbreak of the Masovian War. Radical members would therefore also oppose the expansion of the armed forces, supporting a smaller army so as to reduce the government's financial commitments.

Stance on Reform: Aside from its commitment to classical liberal economic policies, reform was the lifeblood of the Radical Party. Most notably, its members had variously been in favour of the expansion of the franchise since the 1840s, whilst other electoral items were also usually supported. Social reform, however, was a more complex. Though some members of the party may have supported reform on moral grounds, other groups were opposed to legislation such as the Factory Acts on the grounds that it interfered with the freedom of the markets. No Radical, however, was wholly anti-reform.

Stance on the War: The Radicals' stance on the war was notable in that, strangely, it saw the, in full agreement with elements of the Conservative Party. Despite not resigning over the issue, John Bright in particular was a critic of both the war itself and the manner in which it was prosecuted by the military. Viewing the conflict as both a colossal waste of money and energy, during the years prior to the elections the Radicals had come up against their partners in government who were in support of the war on numerous occasions. Whilst remaining professional, Bright's relationship with Palmerston was also strained (further, it could be said) over the matter, with the former only remaining in government out of a desire not to play into Lord Derby's hands and split the government. With the elections looming, however, Bright was now free to condemn the war as vehemently as he wished.

1: With reference to Sir James Graham's comment about the Aberdeen coalition ministry of our timeline: "it is a powerful team, but it will require good driving".

2: Canningites being the followers of George Canning, prime minister for just over one hundred days before his death in 1827, and to a certain extent also the Viscount Goderich, who succeeded Canning and served until 1828. The Canningites were moderate Tories opposed to the 'ultras' under Peel and Wellington, a rather ironic state of affairs when one considers subsequent events. Despite having been courted by, and supporting, both the Whigs and the Tories between 1828-30, they were mostly subsumed by the Whigs in 1830 when they joined Earl Grey to vote against Wellington's government. Notable latter-day Canningites include the Lords Melbourne and Palmerston. For more information about the premiership during the 1820s, see the prologue.

God, you made the Whigs sound so nice and the Tories so boring. Preference, perhaps?

I still hope you're not favoring the whiggies with IG party loyalty support too much, because I anticipate their eventual burning come the 20th century.

I still hope you're not favoring the whiggies with IG party loyalty support too much, because I anticipate their eventual burning come the 20th century.