1. INTRODUCTION.

1. INTRODUCTION.

This thread is a continuation of my earlier thread, The Rise of the Sasanians. Originally, that was intended to be a single thread, but due to “popular demand”, I’ve decided to extend it from a thread telling the story of the appearance and ascent of the Sasanian dynasty to a full-fledged complete history of the Sasanian dynasty from Ardaxšir I until Yazdegerd III. Due to the lengthy time period to be covered and the complexity of the material, I’ve decided to spread it across several threads (I’m still undecided about how many).

Followers of the previous thread will be aware that it’s been at times more of a “tale of two empires” than a mere history of the Sasanian empire, because a central part of the history of the Sasanian empire is its struggle with the Roman empire across four centuries; that’s also influenced by the fact that the overwhelming majority of extant sources are in Latin, Greek, Syriac and Armenian, and necessarily they concentrate on events in the Middle East. Events within Ērānšāhr or along its extensive Central Asian and Indian borders are very poorly covered in the ancient sources, even if those events were as important to the Sasanian kings and the elites of their empire as their wars against Rome.

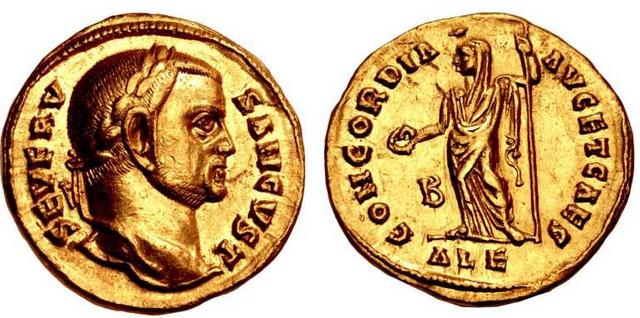

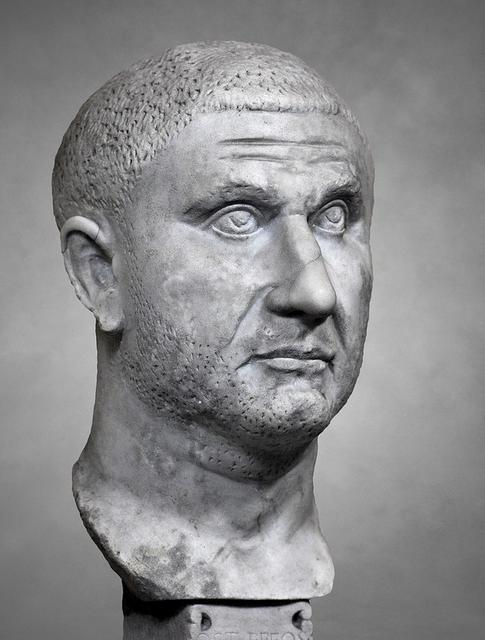

This thread will tell about the reign of six Sasanian kings who ruled during the IV century CE: Hormazd II (302 – 309 CE), Ādur Narsē (309 CE), Šābuhr II (309 – 379 CE), Ardaxšir II (379 – 383 CE), Šābuhr III (383 – 388 CE) and Bahrām IV (388 – 399 CE). The key character among these six kings is by far Šābuhr II the Great (as he’s known in the Pahlavi Books), the longest reigning Iranian monarch in history (and one of the longest reigning monarchs in world history too) who embarked in a bitter conflict against Rome that lasted 30 years until at the Second Peace of Nisibis in 363 CE he was able to reverse most of the losses that the Sasanians had suffered in the First Peace of Nisibis in 299 CE, while at the same time defending successfully the eastern borders of his empire against a new influx of incoming Central Asia nomads (the Kidarites) and the rising Indian empire of the Guptas. His three successors though were far less impressive in this respect and managed to lose all the eastern conquests that Ardaxšir I and Šābuhr I had won during the III century; this marked the beginning of a new era in Sasanian history in which the attention of the kings of the House of Sāsān would be fixated on the eastern borders for a century.

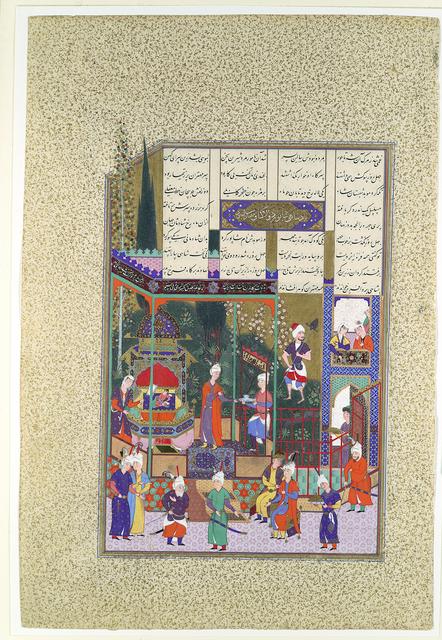

The reign of Šābuhr II is noteworthy also for being the first “golden era” of culture and arts in Sasanian Iran, and for the first serious attempt at a real centralization of the Zoroastrian religion and the establishment of a religious canon of the Zoroastrian sacred works which was probably inspired by the similar efforts that were happening at the same time in the Roman empire, with the first proposal of a Biblical canon by the Patriarch Athanasius of Alexandria. The reign of Šābuhr II saw also the first well attested instance of a widespread persecution of Christians in the Sasanian empire; this was caused by a new phenomenon that was unknown for before the IV century CE: the use of religion as a political weapon in foreign relations, with Constantine I the Great writing to the young Šābuhr II appointing himself the defender of all the “Persian Christians”, which in turn only achieved to turn all the Christians of Ērānšāhr into potential traitors and spies to the eyes of Šābuhr II, who then proceeded ruthlessly against what he saw as a Roman “fifth column” within his kingdom. The conversion of the Roman empire, Armenia, Iberia and several Arab tribes to the Christian faith and the expansion of Christianity among the native Aramaic-speaking population of Asōrestān and Xuzestān would have lasting consequences in the political landscape of the Middle East.

The events in the Middle East during the IV century are exceptionally well documented in the extant sources in comparison to the III and V centuries CE; you’ll notice it immediately if you have a look at the Bibliography in Chapter III of this thread. This is a luxury that we won’t have for most of the rest of these threads. The long war between the Roman augusti Constantius II and Julian against the Sasanian šāhān šāh Šābuhr II in particular is very well documented thanks to a historical document of exceptional quality: the Res Gestae of Ammianus Marcellinus, a Roman army officer who took part personally in all these events and who wrote this history after he retired to the city of Rome in the 370s CE after he left active duty.

The failed campaign of Julian against Šābuhr II really marks a watershed in Roman-Sasanian relations. The border that resulted from the Second Peace of Nisibis would remain fairly stable until the late VI century CE, bringing some political stability to the area, and after this war both empires turned their attention from each other to other borders. In 378 CE the eastern augustus Valens suffered a disastrous defeat against the Goths at Adrianople in Thrace and the long sequence of events that brought about the political disintegration of the western part of the Roman empire began. For the remainder of the IV century CE and all the V century CE the Romans concentrated their attention on their northern borders and on the internal conflicts caused by doctrinal discrepancies among several Christian sects. On the other part, the Sasanian kings would have to concentrate their efforts on their northeastern and eastern borders, where first the Kidarites and later the Hephtalites would pose an mortal danger to the very existence of Ērānšāhr.

This thread is a continuation of my earlier thread, The Rise of the Sasanians. Originally, that was intended to be a single thread, but due to “popular demand”, I’ve decided to extend it from a thread telling the story of the appearance and ascent of the Sasanian dynasty to a full-fledged complete history of the Sasanian dynasty from Ardaxšir I until Yazdegerd III. Due to the lengthy time period to be covered and the complexity of the material, I’ve decided to spread it across several threads (I’m still undecided about how many).

Followers of the previous thread will be aware that it’s been at times more of a “tale of two empires” than a mere history of the Sasanian empire, because a central part of the history of the Sasanian empire is its struggle with the Roman empire across four centuries; that’s also influenced by the fact that the overwhelming majority of extant sources are in Latin, Greek, Syriac and Armenian, and necessarily they concentrate on events in the Middle East. Events within Ērānšāhr or along its extensive Central Asian and Indian borders are very poorly covered in the ancient sources, even if those events were as important to the Sasanian kings and the elites of their empire as their wars against Rome.

This thread will tell about the reign of six Sasanian kings who ruled during the IV century CE: Hormazd II (302 – 309 CE), Ādur Narsē (309 CE), Šābuhr II (309 – 379 CE), Ardaxšir II (379 – 383 CE), Šābuhr III (383 – 388 CE) and Bahrām IV (388 – 399 CE). The key character among these six kings is by far Šābuhr II the Great (as he’s known in the Pahlavi Books), the longest reigning Iranian monarch in history (and one of the longest reigning monarchs in world history too) who embarked in a bitter conflict against Rome that lasted 30 years until at the Second Peace of Nisibis in 363 CE he was able to reverse most of the losses that the Sasanians had suffered in the First Peace of Nisibis in 299 CE, while at the same time defending successfully the eastern borders of his empire against a new influx of incoming Central Asia nomads (the Kidarites) and the rising Indian empire of the Guptas. His three successors though were far less impressive in this respect and managed to lose all the eastern conquests that Ardaxšir I and Šābuhr I had won during the III century; this marked the beginning of a new era in Sasanian history in which the attention of the kings of the House of Sāsān would be fixated on the eastern borders for a century.

The reign of Šābuhr II is noteworthy also for being the first “golden era” of culture and arts in Sasanian Iran, and for the first serious attempt at a real centralization of the Zoroastrian religion and the establishment of a religious canon of the Zoroastrian sacred works which was probably inspired by the similar efforts that were happening at the same time in the Roman empire, with the first proposal of a Biblical canon by the Patriarch Athanasius of Alexandria. The reign of Šābuhr II saw also the first well attested instance of a widespread persecution of Christians in the Sasanian empire; this was caused by a new phenomenon that was unknown for before the IV century CE: the use of religion as a political weapon in foreign relations, with Constantine I the Great writing to the young Šābuhr II appointing himself the defender of all the “Persian Christians”, which in turn only achieved to turn all the Christians of Ērānšāhr into potential traitors and spies to the eyes of Šābuhr II, who then proceeded ruthlessly against what he saw as a Roman “fifth column” within his kingdom. The conversion of the Roman empire, Armenia, Iberia and several Arab tribes to the Christian faith and the expansion of Christianity among the native Aramaic-speaking population of Asōrestān and Xuzestān would have lasting consequences in the political landscape of the Middle East.

The events in the Middle East during the IV century are exceptionally well documented in the extant sources in comparison to the III and V centuries CE; you’ll notice it immediately if you have a look at the Bibliography in Chapter III of this thread. This is a luxury that we won’t have for most of the rest of these threads. The long war between the Roman augusti Constantius II and Julian against the Sasanian šāhān šāh Šābuhr II in particular is very well documented thanks to a historical document of exceptional quality: the Res Gestae of Ammianus Marcellinus, a Roman army officer who took part personally in all these events and who wrote this history after he retired to the city of Rome in the 370s CE after he left active duty.

The failed campaign of Julian against Šābuhr II really marks a watershed in Roman-Sasanian relations. The border that resulted from the Second Peace of Nisibis would remain fairly stable until the late VI century CE, bringing some political stability to the area, and after this war both empires turned their attention from each other to other borders. In 378 CE the eastern augustus Valens suffered a disastrous defeat against the Goths at Adrianople in Thrace and the long sequence of events that brought about the political disintegration of the western part of the Roman empire began. For the remainder of the IV century CE and all the V century CE the Romans concentrated their attention on their northern borders and on the internal conflicts caused by doctrinal discrepancies among several Christian sects. On the other part, the Sasanian kings would have to concentrate their efforts on their northeastern and eastern borders, where first the Kidarites and later the Hephtalites would pose an mortal danger to the very existence of Ērānšāhr.