9.6 INNER POLICIES AND IDEOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENTS IN ĒRĀNŠAHR DURING THE IV CENTURY CE.

Talking about inner developments in

Ērānšahr during the IV c. CE means of course talking about the inner policies of Šābuhr II. His reign of 70 years (309-379 CE) is not only the longest reign in Sasanian history, but also in all recorded Iranian history, and his forceful personality left its mark in the evolution of the royal and religious ideology and in the economy. We know practically nothing about the inner policies of all the other five Sasanian kings who ruled during this century.

According to Perso-Arabic Islamic sources, Šābuhr II continued the trend initiated by the two first kings of the dynasty: he founded new “royal cities” in Āsūrestān and Xūzestān, and also deported Roman prisoners of war into some of these cities. The goal was clear: to develop these provinces where royal authority was stronger in order to reinforce the fiscal base of the crown vis-à-vis the

wispuhrān and

wuzurgān of the Iranian Plateau; the later Islamic sources also attribute to him the foundation of cities in Sakastān, Sindh and Abaršahr (in the modern Iranian province of Khorasan). The cities whose foundation is attributed to this king in the sources are:

- Ērānšahr-Šābuhr in Xūzestān (Karka d-Ledan in Syriac), where Šābuhr II allegedly settled Roman prisoners of war.

- New-Šābuhr in Abaršahr (the modern Iranian city of Nishapur in Khorasan). Here we have a problem, because Ṭabarī attributes its foundation to Šābuhr II, but other sources do so to Šābuhr I. A possibility is that Šābuhr II refortified and enlarged the city as a military base in his eastern wars against the Huns.

- Wuzurg-Šābuhr, close to Baghdad on the west bank of Tigris.

- Ḵorah-Šābuhr; location unknown.

- After a revolt, he took and razed to the ground (using war elephants) the city of Susa in Xūzestān; and later he rebuilt it as Ērān-Xwarrah-Šābuhr (“Ērān, glory of Šābuhr”), known as Karḵa in Syriac texts.

- The name of the city allegedly founded by him in Sindh was Frašāpur or Farršāpur, according to Ibn al-Balḵi.

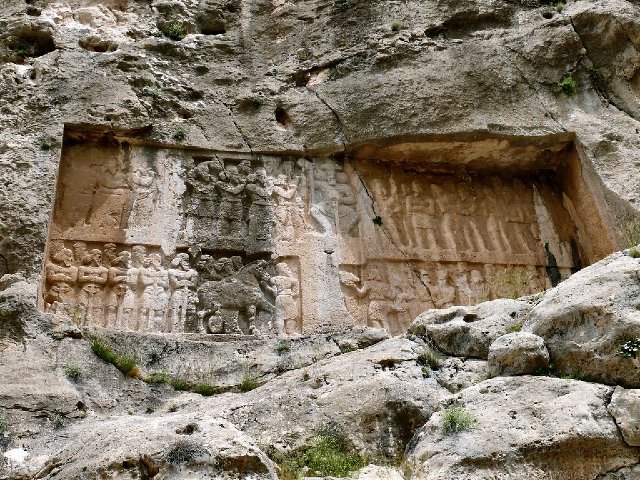

As he was able to sustain a thirty years-long war with Rome, we must assume that these policies succeeded. Šābuhr II’s silver coinage is extremely abundant, a sure sign that under him Ērānšahr enjoyed economic prosperity and the royal finances were in good shape; this is noteworthy considering that he spent almost all of his reign at war against western and eastern enemies, and that one of this wars (against the Romans) was especially long and bitter. Also, the sources don’t talk about any sort of inner rebellion against this king, even if a rock relief at Bīšāpūr shows him in front of the assembled court and grandees of the empire ordering the execution of some people who are beheaded; historians assume that this was made to commemorate Šābuhr II’s victory over some sort of conspiracy or rebellion that has gone unrecorded in the extant sources.

Both in the Zoroastrian tradition and in the extant Perso-Arabic Islamic sources, Šābuhr II enjoys a stellar reputation, better than any other Sasanian king, with the exception of Xusrō I in the VI c. CE (contrary to Ammianus and other Classical authors who described him as little more than the caricature of a bloodthirsty Asiatic despot). This good reputation (the

Šāh-nāma of Ferdowsī even attributes to him Šābuhr I’s victory against Valerian) is obviously inherited (in the case of Perso-Arabic Islamic sources) from the

Xwadāy-Nāmag, the “official history” of the Sasanian dynasty composed initially in the VI c. CE during the reign of Xusrō I. But the Zoroastrian “priestly sources”, the

Bundahišn and the

Dēnkard, also sing his praises, which means that he was truly considered a model king by priests, noblemen and his royal successors.

According to the

Dēnkard, it was during Šābuhr II’s reign that lived one of the towering figures of the Zoroastrian priesthood:

Ādurbād ī Mahrspandān, who according to the Pahlavi Books was the

mowbedān mowbed during the reign of this

Šahān Šāh. According to the

Dēnkard, this priest was a native of the “village

Kurān”; the XII-XIII c. Arabic geographer

Yāqūt al-Hamawī recorded the existence of a village called

Korān in the province of Fārs. So many superhuman and miraculous achievements are attributed to Ādurbād that some scholars have even considered him to be a fully legendary figure. According to a tradition widely reported, Ādurbād successfully underwent the ordeal (

war) of molten bronze (in order to prove the validity of his line of religious tradition; this means that the molten metal was poured onto his chest and survived unscathed. Ādurbād is also mentioned in the

Dēnkard in a description of the Avestā’s twenty-one

nasks; and it may be that he played an important part in the definition of the Zoroastrian canon and that his ordeal related to matters of scriptural dispute. The final version of the canon seems, however, to have been established during the reign of Xusrō I (r. 531-579 CE) according to the British scholar Sir Harold W. Bailey. According to Touraj Daryaee, in keeping with his religious zeal, Ādurbād would have been a force in the enactment and implementing of decrees against non-Zoroastrians; as the “established church” is described as having then fallen on “evil days, plagued by doubt and infidelity”, although I will extend myself later on the supposed “persecution” of religious minorities (especially Christians) in

Ērānšahr during Šābuhr II’s reign. We will see later in this chapter that the American scholar Richard E. Payne disagrees with this vision.

According to Zoroastrian tradition, after the triumph of Ādurbād in his ordeal, he won the ongoing religious disputation against certain “sectaries” and “heretics” and he made the following statement:

Now that we have gained an insight into the Religion (i.e. Zoroastrianism) in the worldly existence, we shall not tolerate anyone of false religion, and we shall be more zealous.

Thus, according to the

Dēnkard, it appears that there was a great synod or council, in which “all people”, probably meaning Zoroastrian theologians, discussed the Zoroastrian material available. It is clear that there were differences of opinion still, because a number of terms for different Zoroastrian] sects appear, such as those of “different groups”, and those who “study the

Nask” of the Avestā. In the apocalyptic Zoroastrian literature Šābuhr II is fondly remembered as the one who “regulated the world and made salvation current among the creatures of the world”, and Ādurbād is remembered as “the restorer of the religion against the heretics”.

In the mid-XX century, scholars accepted on a philological base that the Avestan script which was used by the

mowbeds to write down the Avestā was developed in the second half of the IV c. CE, and could thus be attributed to the end of Šābuhr II’s reign in accordance to Zoroastrian tradition, but in the first decades of the XXI century a closer analysis has debunked this analysis. As the French scholar Philip Huyse showed, the invention of the Avestan script cannot have happened before the V c. CE, and thus it appears that later Zoroastrian tradition just attributed to its favorite king events and inventions that actually happened well after his death.

During the reign of Šābuhr II, the old title of “the divine Mazda-worshipping X, king of kings of the Iranians, whose image/seed is from the gods (

yazdān)” began to disappear from Sasanian coinage. From this period forward there was an ideological reorientation of the royal ideology toward the legendary

Kayanian kings, so that the tale of past was redrawn in a way closely intertwined with the Avestan dynasties. Touraj Daryaee links this with the supposed increase in power of the Zoroastrian priesthood, which would have been the cause that Šābuhr II was the last ruler to claim to be in the image of the gods.

Šābuhr II was indeed the first “imperial” Sasanian king who displayed the epithet “Kay Šābuhr” in his coinage, but as Khodadad Rezakhani noticed, this title had already been displayed in some coins of the Sasanian

Kušān Šāhs and could very well have been that the “imperial” Sasanians adopted an “ideological innovation” from their eastern cousins. The reason for this new ideological trend, rather than in a supposed religious reform or an even less proved increase in power of the priesthood, should rather be sought in the increasing danger coming from the Inner Asian steppe and the rise of the Hunnic dynasties in East Iran.

The lore surrounding the legendary Kayanian dynasty first appears in the Avestā, and was later elaborated in the Zoroastrian Pahlavi Books (book 7.1 of the

Dēnkard is a historiography of the Kayanians) on one side and in the

Xwadāy-nāmag on the other, where the Sasanian rulers of the VI-VII c. CE intertwined their own dynastic history with the legendary history of the Aryans/

Ērān. Following the collapse of the Sassanian Empire and the subsequent rise of Islam in the region, Kayanian legends fell out of favor until the revival of Iranian culture and the rise of New Persian as a language of culture under the Samanid dynasty. Together with the legends preserved in the Avestā, the

Xwadāy-Nāmag served as the foundation of new epic collections in prose, such as those commissioned by Abu Mansur Abd al-Razzaq, the texts of which have since been lost; the best known work of the genre is however Ferdowsī’s

Šāh-nāma "Book of Kings", which (though drawing on earlier works) is entirely in verse, and has remained since the early XI c. CE the national epic of Iran; and by extension the history narrated in it, from the legendary founding of the world until the eve of the Sasanian defeat at the battle of al-Qadisiyyah, became the “National History” of Iran. I have reached a point in these threads where I think that at least a short summary of the “National History” of Iran is no longer avoidable, so I will try to offer a version as condensed as possible.

According to the Zoroastrian creation myth,

Gayōmart was the first human, or, according to the Avestā, he was the first person to worship Ohrmazd. He is rendered in the

Šāh-nāma as

Keyumars (or

Kayumars) and he is made to be first king of the

Pishdadian dynasty of Iran. Following Ferdowsi’s tale, the fourth king

Jamshēd (named

Jam in Middle Persian and

Yima in Avestan -in the

Vendidad-) lost his right to rule (his

farr) when he asked his subjects to be venerated instead of God. Due to this the vassal ruler of Arabia, the demonic

Zahhāk (under the influence of Ahriman in the Avestan tradition) who killed him and usurped the throne of Iran. In turn, Zahhāk (

Dahāka/

Dahāg in Middle Persian) was slain by

Fereydun (Avestan

Thraetaona), a descendant of Jamshēd.

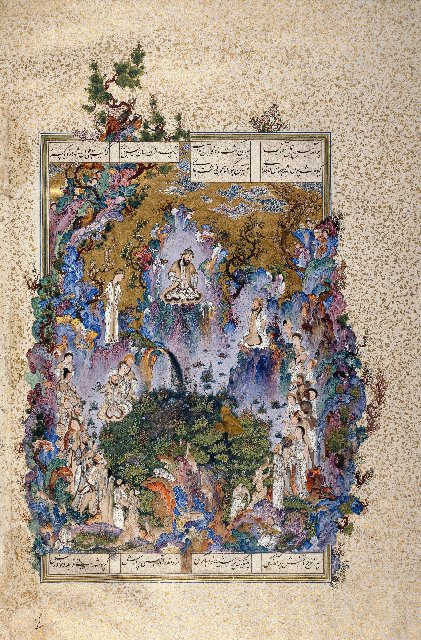

Shortly after Ferdowsi’s death, his masterpiece the Šāh-nāma became immensely popular across the Persian-speaking world and later across the lands influenced by Persianate culture (like the Ottoman and Mughal empires). Increasingly lavish volumes of the Šāh-nāma were produced for Šāhs and Sultans, in which the art of Persian miniatures and calligraphy reached their zenith. The masterpiece of the art of Iranian calligraphy is the Šāh-nāma of Šāh Tahmasp, the second Safavid Šāh of Iran, in the XVI century. This is one of its most beautifully illuminated pages, depicting the Court of Keyumars, the first king of the Pishdadian dynasty.

This mythical hostility between Iran and Tūrān was likely the key aspect that attracted the Sasanian kings once the Inner Asian Huns and later the Türks appeared on the scene, as they would try to portray themselves as the defenders of Iran against its secular enemy Tūrān. In the Avestā, the oldest existing mention of Tūrān is in the Farvardin yašts, which were composed in the Young Avestan language and have been dated by linguists to approximately 2300 BCE. According to the Italian scholar Gherardo Gnoli, the Avestā contains the names of several peoples who lived in proximity to each other: the

Airyas (Aryans),

Tuiryas (Turanians),

Sairimas (Sarmatians),

Sainus (Ashkuns) and

Dahis (Dahae). In the hymns of the Avestā, the adjective

Tūrya is attached to several enemies of Zoroastrianism like

Fraŋrasyan (which appears in the

Šāh-nāma as

Afrāsīāb). The word occurs only once in the

Gathas, but twenty times in the later parts of the Avestā. The

Tuiryas as they were called in the Avestā play a more important role in it than the other neighbors of the Aryans:

Sairimas,

Sainus and

Dahis. Zoroaster himself is implied to have been born among the

Airya people but he also preached his message to other neighboring peoples.

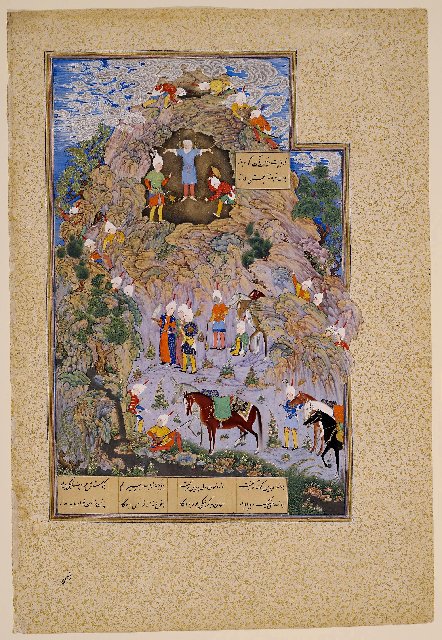

Another of the wonderful miniatures of the Šāh-nāma of Šāh Tahmasp, depicting Zahhāk being chained in Mount Damavand (in the Alborz Mountains) until the End of the World.

In the

Šāh-nāma,

Nowzar is the last Pishdadian king of Iran. On his deathbed, Nowzar's father, Manučehr, told Nowzar to be a humble, righteous king and warned of danger from Tūrān, where enemies of their ancestors ruled. Nowzar took the throne and soon became a weak and greedy king who overtaxed his subjects. Realizing that his kingdom was on the brink of collapse from internal uprisings and the threat of rival kingdoms, Nowzar called on the warrior

Sām (the father of the great hero

Rostām) for help. After rejecting a rebellion that offered to make him king, Sām reminded Nowzar of the counsel his father gave him and Nowzar promised to be a righteous and just king from then on. But as a result of his greed and incompetence Nowzar had lost his divine

farr to rule; while Nowzar tried to stabilize Iran,

Pašang, the king of Tūrān, sent his son,

Afrāsīāb, to invade the weakened kingdom of Iran. Nowzar led an army against the invaders, but he was captured and killed by Afrāsīāb.

In the tradition preserved in the

Šāh-nāma,

Kay Kawād was a descendant of Manučehr who in the Alborz mountains, and was brought to the capital of Iran, Staķr (the Sasanians’ homeland) by the hero Rostām. Kay Kawād defeated Afrāsīāb in personal combat, and for this feat and because he possessed the

farr (Avestan:

xvarənah) he was elected king by the Iranians and founded the Kayanian dynasty, and the descendants of Nowzar (

Zou,

Garšāsp and

Gastham) paid allegiance to him. Of the nine kings of the Kayanian dynasty, the first three (

Kay Kawād,

Kay Kāvus and

Kay Khosrow) spent their reigns battling against Tūrān (the House of Sāsān claimed descendancy from the sixth king

Kay Wahman).

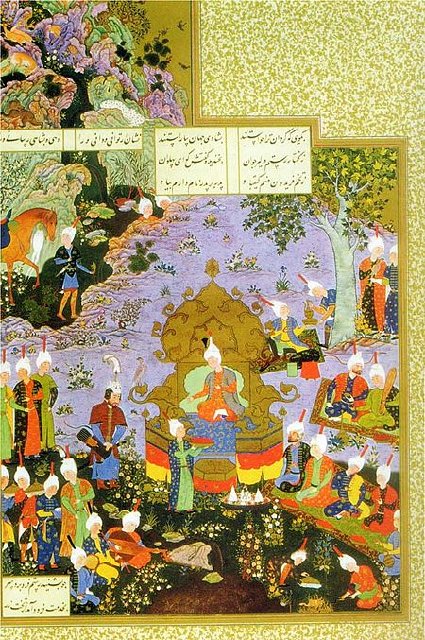

Yet another of the miniatures of the Šāh-nāma of Šāh Tahmasp, depicting the court of the first Kayanian king, Kay Kawād.

In the IV c. CE, as the danger from the East grew constantly and their defeats against the Huns mounted, the Sasanians displayed increasingly this ideology that rooted their dynasty in a legendary past of Iranian and made them descendants of the legendary dynasty that defended Iran against its ancestral enemy Tūrān. In contrast, they toned down their bellicosity towards the Romans, which had been the great “programmatic point” of their rule until then; as Ardaxšir I had toppled the Arsacids on the basis that they had been weak and unable to defend Iran against the Roman encroaching. Šābuhr II’s reign marks the start inversion of this ideology, as the dynasty had to turn its eyes from the West towards the East. This turn would be completed during the first half of the V c. CE, when the Sasanian kings dropped even the title

Šahān Šāh from their coinage, and members and kings of the House of Sāsān began displaying names taken directly from Iran’s legendary history, like Kawād, Xusrō (Khosrow), Jāmāsp, etc. The transition towards a 100% “Kayanian” royal ideology was not complete until the reigns of Yazdegerd I and Warahrān V in the first half of the V c. CE, but it had already started under Šābuhr II.

Other than among his Roman enemies, the was one community among whom Šābuhr II had a truly nefarious reputation: the Christians of

Ērānšahr. In this respect, I will approach now the issue of the historical relationship between the Sasanians, who ruled over a Zoroastrian empire supporting themselves on an explicitly Zoroastrian conception of kingship, and the Christian communities of the empire, who actually were a majority of the population in its western provinces (Mesopotamia, Khuzestan and Armenia, corresponding to the Sasanian territories of Āsūrestān, Nodšēragān, Arbayestān, Xūzestān and Armin). I will follow here the excellent analysis by the American historian Richard E. Payne in excellent his book

A State of Mixture: Christians, Zoroastrians, and Iranian Political Culture in Late Antiquity (which I cannot recommend highly enough to anybody interested in the issue).

Modern understanding of how Zoroastrians regarded the followers and institutions of other religions has been entirely shaped by the famous inscriptions of the

mowbed Kirdēr in the III c. CE (see my previous thread

The Rise of the Sasanians on this subject). According to this

mowbed’s account of his own activities, he built fire temples everywhere from the “heart of

Ērānšahr” in Āsūrestān to its limits in Peshawar. He organized the performance of the

Yasna ritual and instructed believers in the principles of the Good Religion. He also claimed to have “suppressed” the other religions in Sasanian territory:

The Zoroastrian religion (dēn mazdēsn in MP) and the priests held great authority in the empire. The gods, water, fire, and domestic animals received satisfaction, and Ahreman and the demons received blows and suffering. The doctrine (kēš in MP) of Ahreman and the demons was expelled from the empire and became unbelief. The Jews, Buddhists, Brahmins, Nazarenes, Christians, Baptizers, and Manichaeans were struck in the empire. Idols were destroyed, and the residences of demons were eliminated and became the place and seat of the gods.

On the basis of this account, historians have argued that Kirdēr directed a persecution of the religious groups named in his inscriptions, inaugurating a long-term project whose aim was the elimination of religious others, toward which subsequent Zoroastrian religious authorities worked until the fall of the empire. If such was the goal, the flourishing of Jewish and Christian communities from the III to the VII c. CE suggests that they made an extremely poor job out of it. The prophet Mani was slain by royal order for rivaling the ritual power and cosmological knowledge of Zoroastrians, but there is no persuasive evidence for real action against Christians or Jews during the era of Kirdēr’s tenure.

Were Zoroastrian religious authorities inherently persecutory, judging from Kirdēr’s own words? At first glance, Kirdēr’s inscription seems to lump together “the doctrine of Ahreman” (i.e. “idolatry”), and the deviant religions as equivalently evil institutions that Zoroastrians should work to eliminate. But to Payne, a closer inspection, however, suggests important distinctions among these institutions that could have provided a basis for discriminating between different religious groups within a Zoroastrian empire. Ahreman’s

kēš (a term that could designate a doctrine or a sectarian group) was to be expelled. Idols and idolatrous places of worship were to be destroyed. The deviant religions were, by contrast, simply to be “struck”. This implies that they did not need to be destroyed or annihilated, but merely to be “subdued” and put in their “proper place” under Zoroastrian preeminence. Regardless of whether Kirdēr realized or not the claims he pronounced in his inscriptions, he envisioned the “suppression” of religious others rather than their elimination, their subordination to the institutions of the Good Religion, which was to reign supreme in an

Ērānšahr embodying the cosmological ambitions inherent in its doctrine. Christians, Jews, and others were to be disciplined, while supposed “demon worshipers” and “idolaters” were to be destroyed, and it was this task of subordination that Kirdēr set for himself. So, according to Payne his primary goal was to place the Good Religion on solid institutional foundations in an era when the “ideology of Iran” (in Payne’s words) was merely an idea, without fire temples, ritual performances, or laws as its anchors in space and society. He thus not only established such institutions but also propagated the superiority of the religion as the foundation of the new empire in inscriptions and rock reliefs. Thus, according to Payne, the reference to religious others in the inscriptions rhetorically defined the superior position of the Good Religion in relation to its known rivals at the same time as fire temples, a class of religious professionals, and laws were being created. So, in Payne’s view, the undertaking of actions physical or symbolic, such as violence against Christians, Jews, or others, was not necessarily an essential feature of the project of Kirdēr and his successors.

These fine distinctions prefigure the views of later Zoroastrian religious authorities who allowed for the inclusion of subordinated religions in the empire. Payne notices that Kirdēr has too often been seen in isolation by historians, largely on account of his very visible self-promotion, and so they have generally privileged his voice as representative of Zoroastrian religious professionals since his inscriptions are the only extensive contemporary literary sources for their thought. But according to Payne, the views of Zoroastrian exegetes, scholars, and jurists that have been preserved in the IX c. CE collections of Middle Persian literature (the Pahlavi Books) should not be dismissed. They include voluminous discussions of the problem of the place of religious others in a Zoroastrian empire which Kirdēr was perhaps the first to address in writing. There are statements in said texts expressing a positive regard for the

agdēn, “those of bad religion,” within the empire. Zoroastrian discussions of bad religions as social and political problems were grounded in the concerns of late Sasanian scholars over the capacities of humans to contribute to the cosmological struggle that the

Šahān Šāh led in league with Ohrmazd. These scholars were not inclined to the simplistic, binary thinking and blind antipathy toward religious others that the label “intolerant” implies. Kirdēr’s differentiation of “bad religions” into separate categories meriting distinct actions and approaches finds resonance in these later texts that evaluated religious others in terms of a hierarchy of better and worse rather than a binary of good versus evil, that a modern public readily associates with Zoroastrianism.

Scholars have confronted Kirdēr’s inscription and the more militant voices among the later Zoroastrian

mowbeds, with another, larger corpus of sources: East Syrian histories of martyrs. There are nearly sixty accounts written in the Sasanian era of Christians killed at the hands of Zoroastrian religious authorities in the IV-VII c. CE. These describe periods of persecution both before and after the official recognition of the Church of the East by Yazdegerd I in 410 CE. Šābuhr II was believed to have persecuted Christians relentlessly from 340 to 379 CE, the so-called “Great Persecution”; the reigns of Yazdegerd I, Warahrān V, Yazdegerd II, Pērōz, Xusrō I, and Xusrō II were each reported to have contained periods of persecution against the Church of the East, even though its rapidly developing institutions continued to expand unfettered. The catalyst for violence was, in these hagiographical writings, the unwavering hostility of Zoroastrian religious authorities toward Christians. In the accounts of persecution,

mowbeds torment and kill Christians with bloodthirsty glee, devising ever more elaborate modes of torture and execution to inflict as much pain as possible on the persecuted. But in these records, if their willingness to kill Christians and destroy churches was unwavering, their influence at the court of the

Šahān Šāh was supposed to have fluctuated considerably; kings who heeded the

mowbeds persecuted Christians, while those with the will to ignore their demands did not. This ideological framework for understanding the interactions between Zoroastrian religious authorities and Christian communities, derived directly from East Syrian interested self-representation, remains the historiographical consensus to this day; the Christian representation of Zoroastrians, in other words, has triumphed in the modern imagination of the past.

The model proposed by Payne of a differentiated, hierarchical inclusion of religious others rooted in Zoroastrian cosmological thought is a valid one (in my opinion) for an analysis of the processes through which Christians and Zoroastrians reached a working agreement for the former’s inclusion in the empire’s hierarchies and institutions. Concepts of “tolerance” and “intolerance”, with their attached modern notions of liberal political virtue, are unhelpful instruments for the analysis of ancient societies, in part because they do not capture ancient understandings of religious difference and their corresponding practices.

Processional cross belonging to the (East Syrian) Church of the East found in Herat in the easternmost reaches of the Sasanian empire, inscribed with Middle Persian inscriptions in Pahlavi script. Although it is dated to the VIII c. CE, it is a good example of the territorial expansion that the Church of the East enjoyed under Sasanian rule.

Understanding how Zoroastrian elites regarded the human populations of

Ērānšahr requires that we begin with the primordial creation, accounts of which established models for political action. Ohrmazd brought the physical world into being as a vehicle with which to defeat Ahreman, his evil counterpart. His creation was to pass through three successive 3,000-year stages (according to the most prevalent view; there are other ones recorded in the Zoroastrian tradition), in order for the ultimate cosmological triumph to be achieved. This beneficent deity initially created the heavens, water, earth, and fire as well as the primordial plant, animal, and human as wholly good material elements that would serve him in the impending struggle with his evil counterpart. After 3,000 years, Ahreman created material elements of his own (darkness and

xrafstar, wicked animals) and penetrated the good creation with demonic powers, precipitating an era of confrontation between good and evil supernatural forces acting through their respective good and evil creations. This age of struggle constituted the 3,000-year period of human history in which Zoroastrians lived in Late Antiquity. The arrival of a messianic figure, the

Sōšyāns, was to mark the end of the age, indeed the end of history, and the beginning of a world restored to its state of primordial perfection, the

frašgird. The intervening period of human political history was known as the “state of mixture” (

gumēzišn). During the “mixed age”, Ohrmazd and his supernatural allies waged war against Ahreman by means of good creations, enlisting the stars against demonic planets, crafting mountains to make waters flow into pure, life-giving reservoirs, and revealing religion and its rites to humanity. Every component of the material world of necessity participated in the cosmic struggle. But humans played a special, even key, role. As fundamentally good creations, they contributed to Ohrmazd’s restorative work by means of their mere existence, like flora and beneficent fauna. The revelation of Zoroastrianism, however, gave humanity a package of rituals and actions through which men and women could not only support the efforts of the good deity but also accelerate the gradual victory of good over evil, tipping the balance in the meantime in favor of Ohrmazd even as humans continued to await the

frašgird. It was the capacity to choose whether or not to serve the forces of good that distinguished humans from other corporeal creatures in the

gumēzišn.

Lake Hamun in Sistān (Sakastān in Middle Persian) was somewhat of a “sacred lake” to Zoroastrians, as it was believed that the Sōšyāns would rise from its waters.

The implications of this understanding of the nature of the world and humanity for the politics and society of

Ērānšahr were huge. The empire was conceived as a vehicle (akin to Ohrmazd’s original creation) for organizing collective actions to maximize the contribution of humanity to the cosmological struggle. Through the creation of fire temples for the performance of the

Yasna, the extension of arable lands for the cultivation of plants, and the creation of legal institutions to heighten human fertility,

Ērānšahr anchored what was a global restorative project in the territories that the Sasanians ruled. The responsibility for organizing and operating these cosmological institutions rested with a privileged, comparatively narrow group of men: those descended from the first man,

Gayōmart, via the primordial kings through the Kayanian dynasty, which accepted and propagated the teachings and rituals of Zoroaster into the present; that is, the Sasanians and their allied aristocratic houses that constituted the

ēr, the “Iranians.” To be Iranian was first and foremost to possess an ethical disposition transmitted via a lineage that made one an ally of Ohrmazd more efficient in facilitating the cosmological struggle than any other sort of human. This branch of humanity enjoyed such superior ethical qualities as loyalty, righteousness, and nobility that rendered theirs a “lineage of leaders” (

dahibedān tōhmag in Middle Persian).

The

ēr were also those who had full knowledge of the religion that Zoroaster had revealed. According to accounts circulating in the Sasanian period, Ohrmazd created his messenger as a means of communicating the instruments through which humans could act, think, and organize themselves in ways that would help him in the cosmic struggle. The seventh book of the Dēnkard summarized thus Zoroaster’s contribution:

From the all-knowing creator Ohrmazd, he received utterly complete (and even oral) knowledge of the theory and practice of the priestly, warrior, agricultural, and artisanal classes. At the command of the creator he also brought the entire Mazda-worshiping religion (dēn mazdēst) to the king Kay Wištasp, (…) enlightening with the greatest light the wise men in the clime [kišwar] of the most exalted, the gods’ ruler, [and] spreading [the religion] in the seven climes.

It was the Kayanians of

Airyana Vaēĵah (the family of the mythical king Wištasp, who had supported Zoroaster) who received the fullness of religion and directed its distribution to the other six

kišwar on earth. The extent to which other lands and peoples gained possession of the Good Religion, whether fully or fragmentarily, depended upon the Iranians to whom Zoroaster had entrusted its principles and practices. The connection between “Iranianness” (

ērīh) and Zoroastrianism was basic to the self-understanding of the

wehdēn (adherents of the Good Religion) in Late Antiquity. Zoroastrian scholars usually equated the two, using the adjectives

ēr and

wehdēn as virtual synonyms. And although ancient scholars emphasized the ethical content of

ērīh, its foundations always resided in lineage, in genealogical relationships with the

ēr of Zoroaster’s mythical homeland. The flexible nature of Iranian mythical histories allowed individual people of diverse backgrounds to construct such relationships with the Iranians, if not to become

ēr themselves, although there is no documented case of a convert to Zoroastrianism becoming fully an

ēr. It was unthinkable, on the other hand, for an Iranian to abandon the Good Religion or for an

agdēn to lay claim to the adjective

ēr. If the injunction to propagate the Good Religion beyond the

kišwar of Iran shows that Zoroastrianism was not a religion exclusive to Iranians, the privileged position of the

ērān possessing superior knowledge of religion was unassailable.

Iranians, however, were not without their imperfections. As the efficacy of the Good Religion depended on practice rather than mere belief, the possession of

ērīh implied certain ethical obligations, which Iranians invariably fell short of fulfilling. The capacity of Iranians for inaction or even wicked action in the service of Ahreman could destabilize the boundaries between the

ēr and the

anēr (non-Iranians). As one of the scholars quoted in the sixth book of the

Dēnkard pointedly stated:

There is no person in whose substance these things are not found: knavery, the condition of a whore, sorcery, and non-Iranian behavior [anērīh].

Juxtaposing “non-Iranianness” to some of the worst sins underlined how dimly scholars (in comparison with their superiors) saw

anēr, while admitting some overlap in their capacities for ethical practice. Cosmologically efficacious practices were, moreover, available even to non-Iranian

agdēn. The same text that recounts Zoroaster’s revelation of religion to the Kayanians also mentions the activities of earlier

waxšwar, “spirit-bearers,” who brought individual components of religion to humans. These unnamed agents of Ohrmazd introduced various beneficial practices to humanity. In particular, they taught cultivation, husbandry, and craftsmanship to the first couple and ancestors of all humans,

Mašyā and

Mašyānē. The descendancy of this couple retained these capacities even as they strayed, like their primogenitors, into demon worship or other destructive activities. Thus, according to some Zoroastrian scholars, the perfection of the

frašgird was the common inheritance of humanity, and Zoroastrians and non-Zoroastrians alike would ultimately enter paradise. Although Zoroastrians developed decidedly hostile views toward non-Iranians and non-Zoroastrians, the notion that

waxšwar preceding Zoroaster had granted most aspects of human culture and civilization, including the seeds of what it meant to be pious and righteous, as the inheritance of all humans provided the ideological foundation for acknowledging the potential contributions of

agdēn to

Ērānšahr.

If humans found themselves collectively in a state of mixture, there was only one Good Religion that could bring the world to a state of perfection. Every other system of ritual and belief was “bad religion” (

agdēnīh) whose institutions were irredeemably deficient and potentially maleficent. The concept derived from the Avestan

aka-daēnā* (evil piety) or, in the understanding of Sasanian scholars who took

daēnā to designate a belief system, “evil religion”. The Middle Persian term

agdēn became common in the discourse of Zoroastrian scholars in the Sasanian period as a blanket designation for non-Zoroastrians, collapsing the distinctions among Christianity, Judaism, and other religions into a single binary opposition between the single Good Religion and the various bad ones.

Agdēn and

anēr became as synonymous as

wehdēn and

ēr.

But besides this straightforward representation of Zoroastrian concepts of religious difference, there are also more nuanced discussions of

agdēn in the literary sources that priestly and courtly elites produced in Sasanian times. The idea of bad religion was just the beginning a of scholarly discourse on the relationship between the

wehdēn and the great number of humans who stood outside the Good Religion yet within

Ērānšahr. The religions lumped together under the concept of

agdēnīh were in fact distinguished into more or less deficient varieties, only a select few of which merited eradication and/or expulsion. Some ancient scholars went so far as to suggest that in the state of mixture, adherents of bad religions could make valuable contributions to the cosmological struggle. Zoroastrians did not practice a rough tolerance of non-Zoroastrians in the manner of say, crusader Christians, who tolerated heretical Christians, Jews, and Muslims in their territories but would have preferred forcibly to convert them. Rather, Zoroastrians possessed ideological foundations for enlisting the adherents of some bad religions, such as Christians and Jews, into their imperial/cosmologic project.

The presence of

agdēn in Iranian territories and societies had the potential to disrupt the Zoroastrian social order in one particularly important domain: purity. The evil forces of Ahreman, in Zoroastrian thought and practice, operated through physical manifestations, such as drought, winter, locusts, corpses, disease, and menstruation. If the material world was in a state of mixture of rival powers and creations, one of the tasks of the

wehdēn was to disaggregate these entities, to carve out spaces purged of evil that could provide a platform for combat against the material and spiritual agents of Ahreman. This took the form of rites of purification that protected the good elements (the human body, water, earth, fire, and so forth) from evil forces. The constant maintenance of the purity of the body and the natural environment was the task not only of the priests but of individual believers. Of greatest concern for the social history of Iran was the treatment of bodies, especially after death. As the demon

Nasuš was believed to have infected corpses, the dead became repositories of evil and had to be kept distant from living bodies, water, and earth. The exposure of corpses, which dogs and vultures, both beneficent creatures with special powers against the demon

Nasuš, picked clean, was characteristic of Zoroastrian societies from the Achaemenid period onward. The dry bones of the dead were placed in ossuaries (

astōdān) which have been attested archaeologically throughout Iran and Central Asia. This was a potential focus for conflict with Christians and Jews, neither of whom were inclined to follow this practice, either by custom or by religious command.

According to East Syrian hagiographical and historiographical traditions, the Christian populations of

Ērānšahr were subject to systematic persecution from 340 CE until the death of Šābuhr II in 379 CE. More than forty works describe Zoroastrian religious authorities relentlessly tormenting Christian men and women at every possible opportunity on account of their religious identities. Zoroastrian

mowbeds reportedly aimed to eliminate “the Christian people,” who were a threat to the religion, society, and political structures of

Ērānšahr, for example in the

Martyrdom of Aqebshma:

The Christians are destroying our teaching. They are teaching people to serve only one God, not to worship the sun, not to honor fire, to defile the waters with despicable ablutions, not to marry women, not to produce sons or daughters, not to enter battle with the kings, not to kill, to slaughter and eat animals without murmuring [the ritual prayers], and to bury and to conceal the dead in the earth. They say that God created serpents and scorpions together with vermin, not Satan. They impair many of the servants of the king and teach them the sorcery that they call books.

So, according to this statement, because of their evil beliefs and practices, Christians were to be expunged from the empire. This passage is characteristic of East Syrian hagiographical literature in emphasizing the

mowbeds rather than the

Šahān Šāh or the aristocracy as the instigators of persecution. Nevertheless, the outpouring of Zoroastrian hostility toward Christians takes place, in these early accounts, at the command of a

Šahān Šāh, who often directly supervises the torture and execution of the martyrs. These final accounts were, after all, written at a comfortable distance from the purportedly persecutory ruler (Šābuhr II in this case), during the V, VI, and VII c. CE, when East Syrian leaders had come to enjoy the patronage of the Sasanian monarchy. Despite this gap in both chronology and political context, modern historians have usually interpreted accounts of violence during the reign of Šābuhr II as reliably documenting the activities of a Zoroastrian ruler and/or religious authorities hostile toward other religions, something that Payne puts into question.

Stucco portrait of Šābuhr II that originally formed part of the inner decoration of an aristocratic manor at Hajjiabad in Fārs. Excavated by Massoud Azarnoush in 1994.

In the traditional narrative, Šābuhr II initiated a persecution of Christians in response to the conversion of Constantine the Great and the Christianization of the Roman Empire. It was not until the Romans became Christian, as most subsequent historians have asserted, that the Iranian court targeted Christian communities as latent extensions of the Roman state in their territory. Two sources claim thus: the letter that, according to Eusebius of Caesarea, was sent by Constantine I to Šābuhr II (see one of the previous chapters in this thread), and East Syrian hagiographical works in which persecuted Christians are accused of supporting the Romans. According to Eusebius’

Life of Constantine, the first Christian emperor appealed to Šābuhr II circa 324-337 CE to respect the Christians of

Ērānšahr, who came under Constantine I’s protection as the universal ruler/protector of all Christians. If the letter reached the Sasanian court (a highly uncertain event in Payne’s opinion) Šābuhr II would have perceived its claim as an infringement on his own pretension to universal sovereignty. But the view that the letter inspired the

Šahān Šāh to act against the Christians of his empire as agents of Constantine relies on a bishop’s rewriting of a Roman imperial epistle to reconstruct the decision-making processes of a foreign court.

It was not until the mid-V c. CE, moreover, that East Syrian authors began to report that Šābuhr II had accused Christians of harboring Roman loyalties. These allegations appeared in a specific literary context: hagiographers who argued that Christians could be loyal servants of the Iranian court as long as their obedience was compatible with their Christianity were the same authors who reported accusations of divided loyalties. The literary

topos of a

Šahān Šāh denouncing a Christian for serving the Romans provided a target for hagiographers who insisted on the undivided allegiance of East Syrian communities to

Ērānšahr. These representations also gained plausibility from the V c. CE circumstances in which they were written: as Christians became courtly elites serving as diplomatic intermediaries between the two empires, the question of their loyalty and disloyalty became acute. Only a Christian performing a service on behalf of the

Šahān Šāh, such as the

catholicos of the Church of the East

Baboi (d. 484 CE), could be seriously accused of treason. In the IV c. CE, however, Christians could not be identified as agents of Rome. In Payne’s view, even if Šābuhr II received and read a letter from Constantine I, the argument that the Sasanian court perceived Christianity as a Roman phenomenon overestimates the extent to which the Roman state presented itself in Christian terms.

According to Payne, the cause for the violence that Christians met under this king was a matter of internal politics only indirectly related to the Roman wars. To reconstruct the historical events that were reworked into a narrative of a “Great Persecution,” Payne relies on critical studies of the hagiographical accounts that constitute our only substantive (bun tendentious) sources. The most detailed, extensive, and influential of these are the

History of Simeon and the

Martyrdom of Simeon, both narratives of the bishop of Vēh-Ardaxšir whose martyrdom marked the beginning of the violence. Although historians have tended to use these texts as reliable accounts of the events, the German scholar Gernot Wiessner demonstrated time ago that they represent distinct hagiographical traditions compiled in the course of the V c. CE, which in turn shaped the great bulk of the other surviving East Syrian narratives of martyrs from the reign of Šābuhr II. Wiessner also established a foundation for their reliability as historical sources, with the demonstration that the

History of Simeon and the

Martyrdom of Simeon share a common source, likely composed in the immediate aftermath of the martyr’s death. Details that these two texts share therefore can be accepted as historical.

The

History of Simeon and the

Martyrdom of Simeon agree on one essential feature of the violence: its cause. According to the authors of both works,

Šābuhr II had Simeon and his associates executed for refusing to collect taxes on behalf of the court. From his summer palace in Xūzestān, the

Šahān Šāh issued a decree to the authorities in Vēh-Ardaxšir and Ctesiphon, including the bishop, in the

History of Simeon:

As soon as you see this command of ours (…) arrest Simeon, the head of the nasraye (i.e. the Christians), and do not release him until he signs a document and takes it upon himself to collect and give to us a double poll tax and double tribute from all the people of the nasraye who are in our land (…) and who inhabit the land of our authority (…). They dwell in our land, yet they are of one mind with Caesar, our enemy. And while we fight, they rest.

Christian hagiographers insisted that this edict was the stimulus of the “Great Persecution”. Although they described events to present Šābuhr II as requiring Simeon and the other martyrs to worship the sun and the Jews as instigators, these were secondary developments to an attempt to coerce the bishop of the imperial capital to contribute to the imperial tax coffers. The Martyrdom of Simeon explicitly asserted that just as Antiochus IV had plundered the Jews to replenish his treasury during the era of the Maccabean revolt, Šābuhr II had endeavored to despoil the Christians, whose leader steadfastly resisted. The account of a

Šahān Šāh seeking the collaboration of religious authorities in the levying of taxes in preparation for military campaigns is quite plausible. When the edict was made public, Šābuhr II was in the middle of gathering resources for the Nisibis war.

Stucco statue (probably of a saint) from a Late Sasanian church in Vēh-Ardaxšīr. Christian churches were as lavishly decorated with extensive stucco decorations in the interior as Sasanian palaces. Museum für Islamische Kunst – Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

According to Payne, early Sasanian infrastructures of taxation appear to have been underdeveloped. There is currently little documentation concerning the levying of taxes during the first two centuries of the empire, even if the regular minting of silver drachms throughout its territories shows that the Sasanian court enjoyed a reliable influx of precious metals. Early Sasanian efforts to intensify and control the production of high-value commodities in Xūzestān nevertheless suggest that the court sought to overcome the limitations of its fiscal system by finding other sources of revenue. Due to the navigable rivers debouching into the Persian Gulf that crossed the cultivated plains of the region, its cities were ideal sites for the production of commodities specifically for long-distance exchange. Šābuhr I and Šābuhr II built new cities in Xūzestān, in particular

Beit Lapat/

Gundešapur (Middle Persian

Vēh-Andiyōk-Šābuhr) and

Karka d-Ledan (Middle Persian

Ērānšahr-Šābuhr) respectively, for the resettlement of artisans from the Roman world who specialized in the production of high-value textile and precious metal commodities. So central was commercial production at Karka d-Ledan to the treasury of Šābuhr II’s court that he established his winter palace in the city, alongside a structure built to house the administration of its artisans. In addition to concerted efforts to profit from long-distance trade, East Syrian hagiographers reported that the

Šahān Šāh attempted to enlist bishops in the fiscal system. The turn to religious authorities as intermediaries with provincial populations or, even more directly, as supervisors of taxation was in keeping with what is known of Sasanian practice in later periods. Xusrō I would depend on Zoroastrian religious authorities to enact and enforce his reforms of the fiscal system in the VI c. CE. In cities with substantial Christian populations, bishops would have been indispensable auxiliaries for organizing the levying of taxes. In requesting that Simeon and his other episcopal colleagues contributed to the collection of taxes among their Christian constituencies, Šābuhr II aimed to draw upon their authority over the Christian population in the two regions economically most important to the court, Mesopotamia and Xūzestān, to maximize royal revenues to finance war against Rome. Thus, according to Payne the royal edict requiring Simeon to collect taxes was an invitation to participate in the extension of imperial fiscal structures rather than an act of persecution.

But to the eyes of Šābuhr II, the refusal of the empire’s leading bishop to contribute to the war effort was an act of contumacy deserving punishment. Simeon reportedly regarded the collection of taxes as outside the scope of his authority as a bishop, in a passage of the

History of Simeon that communicates his unfailing loyalty to the House of Sāsān:

I bow to the king of kings, and I honor his commands with all my power, however, concerning that which is required of me in the edict, I believe even you know that it is not my business to demand taxes from the people of Christ, my Lord. Indeed, our authority over them is not in the things which are seen but in those things which are unseen.

The author of the

History of Simeon drew a distinction between the worldly authority of the ruler and the spiritual authority of the bishop, which provided an intellectual foundation for Christians in both ecclesiastical and secular offices who served the

Šahān Šāh in imperial institutions. The refusal of Simeon to collect taxes established in Christian discourse a separate, secular space for the Sasanian state, in which the ecclesiastical leaders of the Christian community could only assume roles if their service complemented their spiritual responsibilities. The importance of this distinction between the secular and the ecclesiastical that the V c. CE anonymous author articulated would reappear in Christian hagiographies until the end of the Sasanian empire. Simeon, in this view, could not collect taxes, because such service affected the welfare of Christian communities. But if the separation of worldly and spiritual spheres became common language in the writings of East Syrian leaders, there was no consensus on the tolerability of participating in the fiscal system. The only bishop of Vēh-Ardaxšīr/Ctesiphon to have left behind letters on the secular affairs of the office clearly understood that collaborating in the organization of taxation was a fundamental episcopal responsibility: Ishoyahb III, in the middle of the VII c. CE, even sought to arrogate to himself the privilege of levying the land and poll taxes (precisely the combination rejected in the accounts of Simeon) on the Christians of

Ērānšahr. The views of the bishops of the imperial capital and other sees in the centuries in between these two extreme positions have not survived. There is, however, a hint in the

Martyrdom of Simeon that not all bishops rejected the opportunity to collaborate in the collection of taxes as utterly as Simeon did. Although almost all of the bishops of the other major cities of Xūzestān were executed together with the bishop of Vēh-Ardaxšīr/Ctesiphon, the bishop of Karka d-Ledan, the site of Šābuhr II’s palace, was spared. He was perhaps among the dissenting East Syrian leaders against whom the authors of the

Martyrdom of Simeon and the

History of Simeon wrote their elaborate, theologically detailed expositions of the view that taxation was incompatible with episcopal office: an alternative conception of the relationship between the worldly and the spiritual was clearly not an innovation of Ishoyahb III in a later century.

The great rock relief of Šābuhr II at Bīšāpūr. He was clearly a king not to be messed with. He presides severely over his gathered court and army while some severed heads are presented to him; scholars think that it commemorates the suppression of some unknown revolt by the Šahān Šāh.

So, according to Payne, Simeon and other ecclesiastical leaders were executed in the 340s CE for failing to cooperate in the extension of the fiscal system, not simply for being Christians. Execution was the consequence for disobeying a

Šahān Šāh, whether the offender was Christian or Zoroastrian, an aristocrat, or a commoner. Unlike their Roman peers, Iranian elites regardless of their status or background enjoyed no exemption from body punishment. The violence that followed Simeon’s disobedience targeted ecclesiastical leaders associated with the bishop and his circle, with only a handful of documented secular Christian men and women being involved for the actions of their leaders. Among the Christians executed in the outskirts of Karka d-Ledan in 344 CE were the bishops of

Beit Lapat and

Ohrmazd-Ardaxšir in Xūzestān and

Prat d-Maishan and

Karka d-Maishan in Lower Mesopotamia, ninety-seven priests and deacons, two members of the secular Christian elite who associated themselves with the recalcitrant bishops, and an ascetic woman. More or less reliable accounts describe the execution during the following three decades of bishops, priests, and ascetics in Vēh-Ardaxšīr/Ctesiphon and

Kaškar in southern Mesopotamia; Arbela,

Karka d-Beit Slok, and their hinterlands in northern Mesopotamia; and Xūzestān. In Payne’s opinion, in the absence of source-critical studies of these martyrologies of the sort that Wiessner and other, more recent scholars have performed for the Simeon accounts, the historicity of these martyrdoms after 344 CE remains uncertain.

Southern Mesopotamia and Khuzestan in the Sasanian period, with some of the cities mentioned in the text.

To summarize: the violence that the Sasanian court inflicted on Christians was restricted to its religious leaders who had failed adequately to fulfill the obligations that the court imposed on them, and Šābuhr II punished ecclesiastical leaders for disobedience. Neither he nor his court persecuted Christians as a collective. To Payne, the “Great Persecution” was thus a myth.

The measures of Šābuhr II and Yazdegerd I in the early V c. CE went thus in the same direction, equally intended to integrate Christians into imperial networks and to discipline Christian communities into a subject position dependent on the

Šahān Šāh and his court. Accounts of violence against Christians in the IV c. CE suggest that Christian ecclesiastical leaders, secular elites, and their subordinate communities were becoming “visible” to a court eager to organize of the populations and resources under its control with a view to maximizing their exploitation. If the Sasanian court had to learn how to negotiate with Christian communal leaders during the decades between 379 and 410 CE, East Syrian leaders had to come to terms with Iranian political power within their own religious and doctrinal framework too.