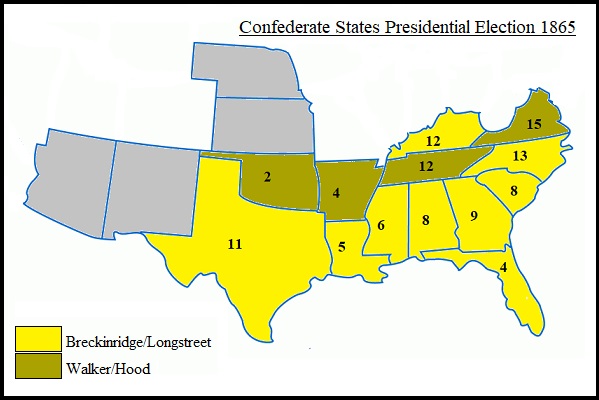

_-_Prado.jpg)

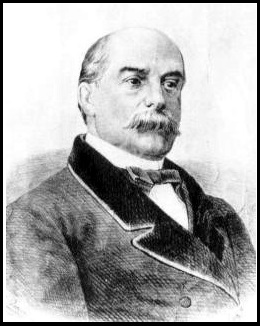

King Ferdinand VII of Spain.

Prologue: The Reign of Ferdinand VII

Few kings died as unmourned as Ferdinand VII of Spain. Few reigned as poorly.

Spain in 1833 was a country both exhausted and angered. The struggle against Napoleon and his brother, the would-be ‘King José’ had seen bitter hardship but also great heroism by the long suffering people of Spain. They would never forget that they had been the ones who first broke the invincible legions of the Emperor, that Spanish courage and cleverness and sheer stubbornness had ground away the proudest and greatest army in Europe.

The twenty years after that heroic age had brought only disappointment. Ferdinand, whose throne countless sons of Spain had bled to restore proved himself a tyrant and a fool. No one perhaps could have won back the territories in the Americas as they blossomed into revolution but the monarch turned probability into certainty. At the very least he turned revolution abroad into revolution ay home. The liberal constitution of 1812, created by those who had fought Napoleon had made Spain a constitutional monarchy. As soon as he could Ferdinand had abandoned the constitution and ruled by personal decree. The result was that in 1820, less than a decade after revolt had restored him Ferdinand became a prisoner in his own country.

In 1823 the French invaded again, this time to rescue Ferdinand from disaster and defeat. The Spanish king, restored to power by the bayonets and musket fire of the French had promised to treat properly with the rebels should he be freed. Characteristically he broke his word and the reprisals so shocked the comte d'Artois, the future Charles X of France – no sympathiser with the liberals – that he refused military decorations from the restored Ferdinand.

The ‘ominous decade’ that followed the French invasion saw the King continue his reign in the manner of the despot. Liberals were exiled, as were those more conservatively inclined who fell afoul of the monarch’s whim. Spain was no stranger to absolutism, but Ferdinand would have been a bad ruler in any century and the century he lived in was one that had in many cases abandoned the style he preferred. The collapse of French absolutism in 1830 was a sign that Ferdinandism had little future.

And yet perhaps there were those who would miss what Ferdinand represented even if they did not miss the man himself. The great aristocrats and the Church, those pillars of Old Spain looked anxiously at the liberals in France and elsewhere. They feared for their privileges but it was not privilege alone that motivated them. The Terror was within living memory. Who was to say Spain would long remain stable under the constitution of 1812?

There was also at least one area of Spain where the people would champion Ferdinand against the liberals. The Basques had not supported the constitution of 1812 which had ignored their ancient freedoms in favour of centralised state. For these people the ascendance of the liberals was a sincere threat.

Queen Maria Christina of the Two Sicilies, widow of Ferdinand VII and mother of Queen Isabella II.

Matters came to a head in 1830. That year Ferdinand published the Pragmatic Sanction, abandoning the Salic Law that restricted the throne to males. Ferdinand had not seen the children of his first three marriages live to see their first year. Personal tragedy was averted and the future of Spain changed forever when his fourth wife, Maria Christina of the Two Sicilies gave birth to a daughter in October 1830, followed by a second in January 1832. Both the elder the Infanta María Isabel Luisa (soon to be Queen Isabel II of Spain) and the younger the Infanta María Luisa Fernanda would live to see old age. By traditional Spanish law neither girl stood to inherit the throne for their uncle the Infante Carlos, conde de Molina stood ahead of them in the succession. Or at least he had before the Pragmatic Sanction.

Don Carlos was as absolutist as his brother, though other than his arch conservative views he was generally reckoned a far better man than Ferdinand. When Maria Christina, pushing the rights of her older daughter pressured the dying Ferdinand to make Carlos swear allegiance to Isabella as Princess of Asturias the conde de Molina refused. Unlike Ferdinand Carlos was too pious and honourable (or too stiff necked depending on one’s views) to abandon what he regarded as his divine rights. To Carlos it was not so much that he wished for the throne himself (his supporters were far more forthright than the prince himself) as that he had a duty to uphold the law of both God and the land. For his stubbornness Carlos was politely exiled to Portugal.

Ferdinand VII died on 29 September 1833, his last months a misery of gout. His wife Maria Christina moved swiftly, declaring herself regent and her two year old daughter Queen. Maria Christina had two immense advantages over Don Carlos; she was in Madrid and he was abroad and she was in sympathy with the liberals. That half of Spain that had longed to be free of Ferdinand were cautiously willing to embrace his daughter and widow and soon the exiles began to return.

Don Carlos had moved nearly as fast as his sister-in-law, declaring himself King of Spain. Unfortunately for the would-be monarch when he tried to enter Spain he found his path blocked by armed forces loyal to the Regent and her daughter. He was forced to remain stranded in Portugal, itself undergoing a civil war between rival claimants to the throne until 1834 when he escaped to England and thence to France before finally returning to Spain after various adventures. Once there he established a rival court to Maria Christina in the north of the country.

Less than two years after the death of Ferdinand VII Spain had drifted from turmoil into outright civil war. On one side stood Queen Isabella II and her mother, supported by most of the army and the navy along with the liberals and even many conservatives looking for a compromise between the Spain of 1812 and that of Ferdinand. On the other side was Don Carlos, backed by much of the Church and the old guard of the aristocracy along with the Basques and those who personally questioned Maria Christina's fitness to rule. The other great powers largely supported Maria Christina, hoping for a swift victory and a stable Spain though time would tell if those hopes were realistic.

At the start of 1836 Spain stood impoverished within, diminished abroad and in the process of tearing herself apart. The road back to power, prestige and peace would not be a straight one, if such a road existed at all...

Infante Carlos, conde de Molina (King Carlos V to his supporters.)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_(14597756640).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)