Huzzah! And remember, in alt-hist fantasy writing (I will commit technological apostasy when it comes to 1940-1950 tanks and airplanes (expect G-1tanks, Amiot 357 fast bombers, and rocket-equipped Bloch 150-series if I manage to keep the German beast at bay), but I'll do my best to limit it to the plausible.

Crossfires, a French AAR for HoI2 Doomsday

- Thread starter unmerged(61296)

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Huzzah! And remember, in alt-hist fantasy writing (

) anything is plausible. 10 years out over a modern human history of hundreds of thousands is well within the margin of error!

Well, don't expect Ouragan fighters, ARL-44s or AMX-50s rolling out of the factories in 1939 anyhoo! I want the story to stick to reality as much as possible, if only to keep it as entertaining to readers as it is to write. I tend to the think the easier I have it, the blander it'll get. Fortunately, I have a treasure trove of plausible might-have-beens for France as well as a number of other nations.

OMG. I basically on the whim decided to check what's popular these days by checking the ACA after a LOOONG time (YEARS) not following things here. And I see that you have started this again!

WONDERFUL!

I see the glacial update speed hasn't changed

Also OMG, I do not remember half the stuff that had happened in this. It's been bloody YEARS.

In any case it's nice to see that the usual attention to detail to the sides of the period that often tend to be overlooked that I REALLY liked about this.

WONDERFUL!

I see the glacial update speed hasn't changed

Also OMG, I do not remember half the stuff that had happened in this. It's been bloody YEARS.

In any case it's nice to see that the usual attention to detail to the sides of the period that often tend to be overlooked that I REALLY liked about this.

OMG. I basically on the whim decided to check what's popular these days by checking the ACA after a LOOONG time (YEARS) not following things here. And I see that you have started this again!

WONDERFUL!

I see the glacial update speed hasn't changed

Also OMG, I do not remember half the stuff that had happened in this. It's been bloody YEARS.

In any case it's nice to see that the usual attention to detail to the sides of the period that often tend to be overlooked that I REALLY liked about this.

Hey hey hey whaddya mean, glacial??? I'll have you know I've churned up no less than 4 new 9-page chapters in so many months-ish, sir!

That's the rub with the narrative style, it takes some time to write something useful story-wise. Once WW2 breaks out, I think I'll be able to update faster as the story will require to mix narrative and history-book.

Having had to endure the great misfortune of re-reading the whole story to try and keep it somewhat coherent, I concur : by Jove, what was I thinking? These 120 chapters are crammed full of places, plots, and people, not to mention spelliing and grammatical mistakes.

That pace is indeed terrifyingly quick.Hey hey hey whaddya mean, glacial??? I'll have you know I've churned up no less than 4 new 9-page chapters in so many months-ish, sir!

That's the rub with the narrative style, it takes some time to write something useful story-wise. Once WW2 breaks out, I think I'll be able to update faster as the story will require to mix narrative and history-book.

Having had to endure the great misfortune of re-reading the whole story to try and keep it somewhat coherent, I concur : by Jove, what was I thinking? These 120 chapters are crammed full of places, plots, and people, not to mention spelliing and grammatical mistakes.

I find it takes far longer to do a history book bit of writing as I end up checking everything and digging into the research. I suppose technically it's not the "writing" that takes the time but everything around it, but I think the point still stands.

Looking back on your old work can be a mixed back, yes you see all the old mistakes and plots you started but never finished, but you can also see how much better you recent work is. My advice would be focus on that and not the mistakes.

That pace is indeed terrifyingly quick.

I find it takes far longer to do a history book bit of writing as I end up checking everything and digging into the research. I suppose technically it's not the "writing" that takes the time but everything around it, but I think the point still stands.

Looking back on your old work can be a mixed back, yes you see all the old mistakes and plots you started but never finished, but you can also see how much better you recent work is. My advice would be focus on that and not the mistakes.

Enjoying historical correctness, I see what you mean about the History Book standpoint and the need to check every point you make in it. The snags I run into are generally of the opposite kind : I write a scene for some event where I'm confident I have all the research material, but the scene either does not work, or looks like that exact same scene three chapters ago.

Speaking of research material, I've picked up a nice magazine yesterday, presenting a 1940 proposal for a mixed tanks-mechanized infantry battalion (and division) which could have been fielded in 1941. That will complement nicely a "battle chapter" if I stay in the fight long enough !

So, next update is in progress, roughly half-made or so. It's been splendid weather here, and I've taken off a few days to visit a friend losing his final battle at the hospital. In between, nothing like the challenge of writing a little to keep my mind off nasty stuff. So I promise you, before the end of the week :

- a most important Moscovite meeting

- lovers in Hesseneck finding out for themselves what they would (or wouldn't) do for love

- an assuredly unromantic cruise in the Carribean

And,if I find time and inspiration, some Japanese kabuki, complete with sabers and artillery, because it's been some time we haven't seen the Imperial Army doing what it does best.

- a most important Moscovite meeting

- lovers in Hesseneck finding out for themselves what they would (or wouldn't) do for love

- an assuredly unromantic cruise in the Carribean

And,if I find time and inspiration, some Japanese kabuki, complete with sabers and artillery, because it's been some time we haven't seen the Imperial Army doing what it does best.

Last edited:

Aaaaaalmost done! No kabuki this time, but an additional German chapter instead. Now I only have to write the Carribean part, do a little fact-checking to satisfy my alt-historical correctness obsession, and add a few pictures.

Bugger. Due to spending time with family and sunshine I've fallen behind on my reading, if you update I'll fall even further behind. I thought I could rely on you to keep a proper gap, then you go and spring an update on us after barely a month!Aaaaaalmost done! No kabuki this time, but an additional German chapter instead. Now I only have to write the Carribean part, do a little fact-checking to satisfy my alt-historical correctness obsession, and add a few pictures.

Bugger. Due to spending time with family and sunshine I've fallen behind on my reading, if you update I'll fall even further behind. I thought I could rely on you to keep a proper gap, then you go and spring an update on us after barely a month!

Being unreliable has a certain French je ne sais quoi...

I would actually sympathise if I didn't know for a fact there's no reading gap, at least not as far as my little story is concerned, since you DID read my last update! Speaking of which, you'll perhaps notice I replaced the 141 P locomotive it featured with a 141 C model. Thanks again, BTW for pointing out that mistake!

At least you'll be able to take solace in knowing that the next update will be a little longer than usual, a sure sign I intend to slack off a little before churning up the next one.

Bugger. Due to spending time with family and sunshine I've fallen behind on my reading, if you update I'll fall even further behind. I thought I could rely on you to keep a proper gap, then you go and spring an update on us after barely a month!

Typical Albion...

CHAPTER 121 - LAST MOVES, FIRST MOVES

Moscow, July the 10th, 1939

So, thought Ribbentrop pleasantly, as the two delegations entered the vast meeting room, that’s where they want us to work today. Excellent !

In itself, the room had nothing remarkable. It was a long rectangle, occupied at its center by a large dining table covered in green felt, with two rows of chairs. On each side, another row of chairs was aligned against the wall. The walls were dark green, adorned with a few paintings, mostly of Western European landscapes. On the right-side wall, two darker squares betrayed the recent removal of two frames – official portraits, no doubt. The room had been cleaned by their hosts, who had made a point of leaving the rest of the building untouched. The Soviet officials had guided the German delegates through a series of halls, offices and corridors which looked like they had been abandoned in a hurry – which, Ribbentrop thought, was probably the case. In the offices, the desks and chairs were askew as if the offices’ occupants had been ordered to leave at gunpoint, and the corridors leading to the meeting room were littered with sheets of papers that sometimes took flight when one opened the double doors, briefly lifted by a draft coming from a broken window pane. One type-written page flew past the German Foreign Minister, who snatched it mid-flight and examined it briefly. His fluency in French was next to non-existent, but he recognized the words “Paris” and “Staline” .

With a wan smile directed at his Soviet counterpart, Ribbentrop looked up and made a great show of crumpling the paper in his gloved hand and tossing it aside.

“Meaningless drivel” he said. “Empty promises.”

Across the table, Vyatcheslav Molotov, the People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs, nodded with an affable smile. This talks with the German delegation was of capital importance for the Politburo, and therefore for him personally, and he thus congratulated himself for having picked the place for the meeting. Not that it had been much of a challenge, as Molotov and his aides had had ample time to decipher Ribbentrop during previous encounters. The man could be summed up in one word : vanity. Watching the German strut around what had once been the French embassy to the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, Molotov mused, one could think Ribbentrop had conquered it himself. Such, Molotov knew, was Ribbentrop, and in many ways such was the regime he represented : brutal whenever it was without risk, blustering when it faced resistance, narcissistic in the extreme at all times.

Yet, the Russian reminded himself, the road to the Revolution in Europe once again leads through Germany.

“Shall we begin?” proposed Molotov, inviting the delegates to take their seats, in front of which water jugs and notepads had been placed. He refrained a sarcastic smile as Ribbentrop took off his cap in a flurry, throwing inside a pair of gray felt gloves. Who wore gloves in July?

“I understand”, began Ribbentrop, “that the Soviet government has expressed his readiness to take our partnership to a new, unprecedented level. I am authorized by the Führer himself to conduct any negotiation between our two countries relative to reaching a wider agreement.”

“And I have been instructed by the Politburo, and by First Secretary Stalin personally, to lead our discussions” said Molotov, as German and Soviet aides traded their letters of credentials, making sure both sides were on the same page.

“The past year has shown there were many points of convergence between our two nations” stated Ribbentrop. “I think it is in our mutual interest, as the two strongest powers on the continent, to pave the way for a global agreement that would encompass all areas of possible cooperation and put to rest any risk of misunderstanding or mistrust.”

“Where better to initiate this new era of mutual understanding than in this building ?” said Molotov. “Both our nations face the hostility of the so-called Western democracies. Both our regimes have made the destruction of the bourgeoisie their priority, be that within our borders or...without.”

Ribbentrop smiled at the implication, as German delegates rapidly shared looks. If Molotov really was proposing what they thought, the Wilhemstrasse – and, of course, every one of them - was on the verge of scoring a major political success.

Well, another one in just two years, thought Ribbentrop.

“Does that mean the Soviet government stands ready to discuss matter of… territorial importance?” asked Martin Luther, second-in-command of the German delegation. The security officers attached to Molotov’s staff had compiled a file on this German as well. The portrait they had drawn of Luther was hardly flattering : a toadie, mimicking his boss’ worst traits while having none of its few qualities. While Ribbentrop could be cunning at times, Luther was a ham-fisted brute. And while Ribbentrop had shown earlier he was ready to take some personal risks in pursuing his objectives, Luther emerged as a complete yes-man, mostly preoccupied by currying favour with more powerful party bonzen. This mix of ambition and average intelligence made him, in the Soviet official’s eyes, a most welcome addition to the German delegation.

“The Politburo is of the opinion that we both stand to gain from a bilateral agreement regarding our respective zones of political influence” acquiesced Molotov. “Comrade Stalin sees such an agreement as the logical next step after the economic agreements of the past few months.”

This time, the traded looks on the German side lasted longer.

The rapid deterioration of diplomatic relations between the French Republic and the USSR, and their interruption after the fall of the Spanish Soviet Republic, had been too good an opportunity to pass for Germany. After six years of uneasy coexistence between the Reich and its Eastern rival, the Wilhelmstrasse had immediately reactivated the old influence networks of the 1920s, and German feelers had been extended through third-party nations. At first, the German overtures had been received cooly by the Kremlin. Some Politburo members like Maxim Litvinov, Molotov’s predecessor, had been reserved, if not open hostile, to the idea of a détente with Nazi Germany. Wasn’t Hitler the champion of anti-communism ? Wasn’t the German Reich actively pushing for an anti-Komintern Pact in Asia and Europe ? Weren’t German communists sent to camps by the hundreds, when they were not killed in the streets by the Nazi Stormtroopers ? Others, notably among the junior members and candidates, had been more receptive, sensing this détente could serve their own personal ambitions. The Nazi regime, they said, was not like the bourgeois democracies of the West. It had been opportunistic, harnessing revlutionary forces which might one day escape their control. Couldn’t the USSR hear the Germans out, and see if there was something to be gained for the Soviet regime ? If there wasn’t, the contacts would be broken off, and that would be that. The debate had continued throughout most of 1936, both sides discreetly encouraged by Stalin. As he often did, the master of the Kremlin had waited until both sides were fully committed before showing his hand. He finally spoke on the 5th of january, 1937, during an extraordinary session of the Political Bureau. Nazi Germany, he had finally said, assuredly was a despicable imitation of a Socialist state, mimicking revolutionary fervour but ultimately serving the interest of the petty bourgeoisie as well as of capitalists. As such, though, it constituted a decaying form of bourgeois State, which would only precipitate the destruction of the so-called “democratic” forces and pave the way, ultimately, to a true Marxist revolution that could take the whole of Europe with it. Therefore, any deals with the German Reich would only give it temporary advantages, readily consumed, like crude oil, wheat and ores, while they could allow the Soviet Union to acquire much-needed advanced technical know-how and could even lead to permanent gains in eastern Europe. A true Socialist approach, Stalin said, would thus be to welcome Hitler’s openings with open arms, and get ready to rob him blind. On January the 6th, the Politburo voted unanimously to engage in discreet negotiations with the German Reich. The next day, the Izvestia newspaper announced a partial reorganization of the Politburo: the aging Maxim Litvinov and two of his staunchest partisans had stepped down, temporarily and at their own request of course, on grounds of ill health after years of exhausting work on service of the People. The formulation of the announcement had not fooled the Wilhelmstrasse’s ‘Kremlin experts’: Litvinov was in disgrace, and his dismissal cleared the path for diplomatic progress with the Soviets. Berlin had sent a congratulations telegram to the new Foreign Minister, Vyatcheslav Molotov, and had waited with baited breath for another signal from Moscow. It was not long in coming : on May the 9th, the Soviet ambassador to the Reich had sent a request for an appointment with Ribbentrop : would the Reich’s Foreign Minister be interested in exploratory talks on subjects of interest for both nations ? Three weeks later, the talks were in full swing, broaching a wide range of topics from oil sales to technology transfers, as well as the discreet set-up of German arms firm subsidiaries in Soviet Russia. The partnership, which was hailed in Berlin as a new Rapallo, made the delight of the OKW : safely hidden from Western sight, German-operated plants were manufacturing artillery tubes and small ammunition, German tanks were tested on Red Army bases, as were Messerschmidt and Junkers planes. At the Leningrad shipyards, more than a dozen submarines were being assembled, and welders were working three shifts, under the watchful eyes of KGB sentries, to prepare the launch of the Kriegsmarine’s second aircraft carrier. In Germany itself, the economic accords ensured the continued flow of crude oil, chrome and manganese which the Reich’s heavy industry direly needed. In return, German trains and freighters left for Russia every week or so, either delivering machine-tools and manufactured goods or debarking German engineers and technicians, ready to build new factories in the Soviets’ country.

“Both our nations have vested interests in the Baltic” stated Ribbentrop. “As well as in the Balkans of course.”

“Which only emphasizes the importance of reaching a general agreement”, Molotov approved with a nod. “This is why the Soviet government seeks an all-encompassing pact, ranging from the Gulf of Finland to the shores of the Black Sea, and providing clear guidelines to coordinate our diplomatic efforts in third-party nations.”

At the mention of third-parties, Ribbentrop allowed himself a smirk. The Soviet overture, he felt, was an acknowledgment of the Reich’s leading position in Europe as well as the leverage it could exert in Asia through the German-Japanese alliance and the Antikomintern Pact, which had been his œuvre. The Reich had gladly encouraged Japan’s aggressive stance for the past year, as it allowed Germany to appear as the reasonable partner which could, if properly courted, urge moderation to its Asian ally. The tactic had worked reasonably well with the Western powers, notably the United States. German diplomats had helped defuse tensions after the Imperial Army had shelled foreign legations in China, and even bombed patrol boats flying the Stars and Stripes. Even England and France had had to seek German help to settle a few incidents in which merchant ships had been stopped at sea by Japanese warships and searched for “arms contraband”. Their governments were, of course, acutely aware that many of such incidents had been orchestrated with the full knowledge of the German government, and only aimed at reinforcing both Japan’s and Germany’s position on the international stage by exerting pressure on the Western powers. But in the end, there was no choice. Pragmatism demanded they played with the cards they had been given. And now that Soviet Russia seemed ready to fall into line as well, Ribbentrop was sure the Reich would be able to raise the stakes even higher.

“Perhaps” said Ribbentrop, “we could begin by identifying the areas we consider vital to our respective governments, and which will require the greatest attention. I shall begin by stating we regard our current relationship with Lithuania as pivotal to our position in Eastern Europe.”

“The Baltic is of a particular importance to us. We regard this area, which used to be united with Russia, as a part of our nation, unjustly detached from the homeland. Nevertheless” said Molotov, raising a hand to cut short to any protest from the German delegates “the Soviet government recognizes historic realities, and is therefore ready to accept the preeminence of German interests in this country. If, of course, the German Reich is ready to recognize us special rights to intervene in Latvia and Estonia, which we regard are closest to us in terms of economy, race and culture.”

“Rosenberg will go nuts” whispered Luther, barely concealing his satisfaction at the prospect. The Estonia-born Party ideologue had become the bête noire of the Foreign Ministry, as he kept pushing for the incorporation of all small Baltic nations to the Reich, in the name of racial proximity. Rosenberg’s amateurish crusade for the “Lost tribes of Germany”, as some diplomats called it derisively, irked Ribbentrop to no end. He saw it as an interference with his own efforts and, more importantly, an infringement on his domain. It was high time, he decided, Rosenberg learned to leave weltpolitik to the professionals.

Alfred Rosenberg’s ambitions made him powerful enemies among the Nazi bonzen

“Provided Lithuania’s independence and territorial integrity is guaranteed” said Ribbentrop, “I think the German government will readily acknowledge the Reich has no permanent interests east of Lithuania” said Ribbentrop. Coming for the emissary of a nation which had annexed the city-port of Memel only a few moths before, the mention of Lithuania’s integrity elicited some quick smiles among the Soviet delegates.

“That is noted” said Molotov. “If that position can be confirmed rapidly, it will be an important step towards the general agreement we both desire. I am actually quite confident that we can reach this goal, if we stay true to the prevalent cooperative spirit. As a token of this cooperation, the USSR stands ready to renounce to any territorial claim regarding Romania, provided our basic security concerns are taken into consideration in this country.”

Ribbentrop couldn’t be more happy with himself – Bucarest, indeed, had been the biggest obstacle to a German-Soviet for quite some time. In the past five years, Romania, Germany’s foothold in the Balkans and one of its key sources of oil, had been embroiled in a series of coups and counter-coups which had pitted the NKVD and its agents against the Abwehr’s own networks. In 1934, in the wake of an ill-advised agrarian reform which would have consolidated the position of great proprietaries (among which the Church emerged as one of the biggest) a Communist-led insurrection had erupted throughout the country, forcing King Carol to flee to neighbouring Yugoslavia as the totally surprised Romanian army remained in its barracks and wavered on its loyalties. The newly-installed Communist regime had immediately claimed its solidarity and loyalty to the Soviet Union, purging the government as well as the army of “feudal cronies” and announcing a new agrarian reform aimed at returning “all arable land to the people”. Nine months later, as hurriedly dispatched Abwehr officers discovered, the country was in complete chaos. Dreadfully unprepared for actually running the country, the new government had accumulated the gaffes and alienated almost every group of the country. The Romanian farmers, who made up most iof the country’s workforce, had turned en masse against the new regime when it had been revealed that returning farmland to the people meant handing over their own property, however small, to collective State farms. As a result, the newly-nominated officers of the Army, which had so far observed a prudent neutrality since their units were mostly composed of conscripts from the rural areas, began to renew contact with the court-in-exile. In one of those ironic twists the Muse of History seems to revel on, an unlikely consensus emerged between the German Abwehr and its Western adversaries. : regardless of mutual enmity, Romania could not and would not be allowed to join the Comintern. In face of the Red Menace, it was time to give mésentente cordiale a chance. Giving themselves a little leeway in the interpretation of their government’s instructions, and the Abwehr, Secret Intelligence Service and the Service de Documentation Extérieure officers concluded an informal and uneasy truce, and started coordinating their efforts somewhat. Hitherto quarreling Monarchist, Republican and Fascist factions were urged to set aside their differences willy-nilly, and focus on combating the Communist regime. In Berlin, Paris and London, the spies’ political masters turned a blind eye to the informal deals struck on the ground, while at the same time maneuvering to favour their own protégés when the time would come. In Moscow, where the rank amateurism of the Romanian Communists had rapidly convinced the KGB’s upper echelons it would be useless, and politically suicidal, to try to prop them up, the Politburo decided to let the Romanian revolution succeed or fail on its own. If it succeeded, they would have no choice but to embrace Moscow anyway. If they failed, at least the ranks of Romanian revolutionaries would be purged from their incompetence for a next occasion. In the end, it had been the British who had won the first round of these espionage Olympics : the Monarchists, whom London supported, were the one faction around which the widest political alliance could be built, federating conservative Republicans as well as traditionalist Fascists. While France-backed Republicans had eventually resigned themselves to another decade of monarchic rule, the Nazi-leaning iron Guard légionnaires had not, disregarding their Abwehr advisers’ calls for prudent action. Under the command of their charismatic leader, Capitul Corneliu Codreanu, they had immediately taken to the streets, organizing protests and paramilitary parades and demanding from the government “bolder actions for a stronger Romania”. As it soon appeared, the Antonescu government had every intention to give the Iron Guard what it wanted. In 1937, on Antonescu’s orders, the Romanian Army conducted a series of mass arrests of légionnaires, starting with the Iron Guard’s national and local leadership. While the courts made sure the decapitated rank-and-file guardsmen only faced lenient sentences, the Guard’s upper ranks were offered a clear choice : either they’d fall into line and support the Antonescu government, or they’d enjoy the hospitality of Romanian prisons. With their Berlin protectors ready to wash their hands off them for the time being, the Iron Guard bowed their knees before the throne. As a precautionary measure, Codreanu, by far the hardest of the hardliners, was offered a semi-official exile : he’d either serve as the Romanian ambassador to the French republic, or he would serve a lengthier sentence in jail. Caught between the pleasures of Paris and the hardships of a Romanian fortress, deserted by his German backers, Codreanu had caved in and left for the French capital. The chastised Iron Guard had returned to its barracks-and-campfire activities, and the Romanian government had consolidated its power, gradually drifting towards Berlin. If, Ribbentrop mused, the Soviets were indeed ready to give Germany a free hand in Bucarest, that would definitely secure the Reich’s position in the Balkans.

“What would the Soviet government consider an acceptable quid pro quo for this, ah, recognition of our prevalence in Romania ?”

“A similar recognition from the Reich”, said Molotov looking intently at Ribbentrop, “of our own eminent position in Finnish and Bulgarian affairs.”

Ribbentrop allowed himself a pause to gather his thoughts. Bulgaria, as he knew perfectly well, was already a lost cause. There, the Communist coup which had toppled King Boris’ regime had committed none of the mistakes of their Romanian brothers-in-armbands, and thanks to the nation’s poorer economy there had been far fewer small proprietaries to oppose Dimitrov’s agrarian reforms in the first place. Acknowledging Bulgaria as an integral part of the Soviet sphere of influence would therefore cost little to the Wilhelmstrasse, which had practically written the country off anyway. Finland, on the other hand, was a different matter. There were, as always with Nazi Germany, “racial” issues to be taken into consideration. Nordic brotherhood and other such poetic nonsense, in Ribbentrop’s opinion, but such nonsense nonetheless struck an echo in some of the party’s bigwigs. Finland was part of the Nazis’ Wagnerian mythology, after all, while Romania was, well, clearly foreign. But Romania had oil, and constituted a window opening on the whole Balkans, when Finland only opened West, to a decidedly neutral Sweden and an already sympathetic Norway. When one looked at it dispassionately, Ribbentrop thought, the choice was self-evident : keeping Romania would more than offset the disadvantage if losing Finland. Still, that was a decision he could not take alone, and decided to change tack.

“For a diplomatic decision of this magnitude” he said, “I shall have to confer with the Führer. In the meanwhile, maybe there is another area we could discuss. One area that is of considerable importance to both our nations, and where, if I may say so, our national interest might converge in a very practical way.”

“And what would that be ?” asked Molotov, tilting his head in mock incomprehension. He had been told by his master this moment would come, and had so far – privately of course - discarded the prediction as so much wish-making by the master of the Kremlin.

“Why, Poland of course” said Ribbentrop. “Or, to be more precise, Polish-held territory”

Molotov blinked. It was not everyday, he realized with a chill, that a Communist official could bear witness to the realization of a prophecy.

Hesseneck, July the 11th, 1939

“They stared at me” fumed Otto Abetz, turning away from his young companion. “They were all there, mein Gott, staring at me.”

Sympathetically, the younger man put his hand on Abetz’ naked shoulder. It was a warm day, and both men had been happy to leave the city to enjoy a picnic and a bit of swimming and sunbathing at the Eutersee lake. While the two men were considered what Berliners called ‘beefsteak Nazis’, brown on the outside but still pink-ish in the inside, they wholeheartedly supported the regime’s enthusiasm for sports and nature. It made for a healthier living, they both thought – and it allowed their private pleasures to enjoy that most-desired luxury in modern Germany, privacy.

Their on-again, off-again affair had begun on the benches of the Giessen university, when then thirty-year old Abetz, head of the Sohlberg Franco-German Youth Meeting, had been invited by the Dean of Historical Studies to attend a conference on the Holy Grail and the Albigeois crusade to be given by a young author one year his junior. Mr Rahn, the Dean had told Abetz, had caught the attention of the Reichsführer-SS himself, who had expressed great interest in the book and had encouraged his author to continue his work on the legendary Grail. Abetz, himself a keen amateur of French culture, had found the lecture fascinating – and the lecturer, even more. Rapidly the two men discovered they had much in common, beyond their age and first name : they both came from middle-class Odenwalder families, and shared a common love for French culture and medieval lore. More importantly perhaps, they both were making their own, uneasy inroads through the corridors of Nazi power. Abetz had been a Socialist in his youth, and still professed Pacifist opinions ; Rahn was a mischling through his mother and had not always been discreet about his homosexuality. And yet, both had joined the Party under the auspices of powerful protectors, Abetz to work for the Ausland service with Joachim von Ribbentrop, while Rahn had been recruited in Heinrich Himmler’s personal staff. Both men’s future was as fraught with dangers, as it seemed ripe with opportunities, and the constant ebb and flow between the two submitted Rahn and Abetz to great tensions they seemed to only defuse in each other’s warm embraces. Soon, the opportunistic lovers had become regular confidants.

“Calm down” said Rahn, as Abetz clenched his fists in retrospective rage.

“Can you imagine, Otto ?” said Abetz plaintively. “They looked at me as if I had been a murderer.”

“But you haven’t anything to do with that crime !” said Rahn, opening a battle of fruit juice before extending it to his friend. “What does it matter if these imbeciles looked at you in a funny way ? Soon they will have to admit they were wrong, even that English oaf you keep talking about.”

“Him?” said Abetz, taking a swig of the range-flavoured Vitaborn. “If he saw me healing blind people he’d suspect me of having poisoned them first – I'm serious, he really would! You don’t understand. In your world truth is an absolute. Either a historical event is backed by academic evidence, or it never happened. In diplomacy, only appearance matters. Sure, maybe the French authorities will eventually find the murderer operated alone, and had no relation to me or to the Reich. But that will not matter to the people who were in that room last month. You can bet every Chancellery was cabled that evening that I had personally orchestrated the attack.”

“Oh, believe me, Otto”, said Rahn. “In ‘my world’, as you say, truth has long since ceased to be an absolute. You wouldn’t believe the kind of things I overhear at the refectory. Or when the Reichsführer decides to entertain his personal staff. Nightmares stuff. Blood-curling stuff. Heydrich, Muller, Himmler… the whole lot of them. We lie in bed with monsters, Otto.”

“Well, not always” replied Abetz with a sly smile, eliciting a welcome laugh from Rahn.

“Ain’t you the charmer! But to get back to your affair : don’t you think the French government would have demanded your immediate recall if they really thought you were involved in the attack ? They haven’t expelled you, right ?”

“No” conceded Abetz. “They haven’t. When they meet me, it’s, more or less, business as usual, with only colder welcomes, longer stares, and more guarded words. And it makes it worse, actually. Sometimes I think they just want me to stay in their sights. I keep thinking about von Rath, you know, that young attaché that was killed in the embassy last year… I know, I know, I get paranoid. I need help, Otto.”

“Well, if you are looking for professional help, good luck with that” said Rahn bitterly, lying down on the blanket. Above their heads, drunk with sunshine and shrieking their joy of flying, swallows circled the immaculately blue sky. They wanted nothing to do with the tribulations of men down below, and Rahn could not blame them for that. “My lot are going after all the mind doctors they can. ‘Psychiatry is a Jewish pseudo-science’, my dear Otto.”

“I didn’t mean that kind of help” said Abetz. “What I need is a friend’s help. Your help, Otto.”

“Mine ?” asked Rahn, rolling on one side. “What could I do ?”

“Just what you already do” said Abetz in a pleading tone. “Keep your ears open. See if you can… gather something useful to help me untangle this mess.”

“You’re not asking me to spy on the Reichsführer, are you ?” asked Rahn, dead serious. “Because that is a guaranteed death sentence, that.”

“Grüss Gott, Otto, no !” cried Abetz. “You know I would never – whatever, just keep your eyes and ears open, that’s all. The Ausland Ministry is up in arms about the attack. Joachim – well, the Minister, was besides himself with rage when I cabled my report that… evening. He told me he talked with the Abwehr the next day, and they swore on their honour as German officers their outfit had nothing to do with that.”

“Their ‘honour’, as German officers” repeated Rahn slowly, derision dripping from every word. “Boy, that is solid proof, that. I swear, if you heard what I hear, you’d realize how cheap an officer’s honour comes by, these days”

“I know” sighed Abetz. “Anyway, that’s besides the point. Ribbentrop believes them. He says the Abwehr command is quite angry as well, claiming the attack has endangered most of their intelligence-gathering operations. Canaris is said to be baying out for blood over the whole thing. It seems he has sent feelers in every Berlin and Paris office to sniff out for traces of collusion with the murderer. But as you are well aware, there is one office where his bloodhounds won’t be allowed to poke their nose in.”

“The SS” said Rahn dejectedly. “My... lot.”

“Come on, they’re not your lot, Otto. You have nothing to do with these brutes” said Abetz, placing his hand on his friend’s chest. Rahn’s heart was beating fast. “My, what complicated lives we live, don’t we ?”

“Indeed” replied Rahn, squeezing Abetz’ hand. “Little lambs working on the wolves’ den, serving other little lambs on a platter to the monsters we hate and fear… Of course we can always take solace in knowing we’ll probably be at war soon and maybe everyone will die.”

“You are one of a kind” said Abetz with a soft chuckle. “Otto, I only ask you to tell me what you’ll overhear, that’s all. And I promise you : if you find something that the Ausland Ministry can use, I’ll talk to Joachim. We’ll free you from that black-clad Hell of yours, I promise. Imagine that ? We could work together in Paris, you and me.”

Rahn remained silent. He thought of Himmler’s bizarre pagan rituals at the Hohenlychen castle, of Muller’s sausage-thick fingers when he clenched his fists, of Heydrich’s murderous morgue. God, wouldn’t it be great to never see those faces again ? To abandon them to their cruel schemes and never ever having to think of them ? That would be like a second birth.

“All right” he sighed. “God, the things I would do for love… All right, I’ll be your fly on the wall. Now come hither, Otto. It’s getting cold, all of a sudden.”

Berlin, the Schillerstrasse, July the 11th

“Stabs !” called Lothar Hoffmann, raising his hand so the NCO could see him among the maze of small cubicles.

Stabsfeldwebel Scharr scanned the room and suppressed a grimace of irritation when he located the source of the call. As usual, Hoffman’s uniform vest was unbuttoned, loosely flapping on his shirt. His collar was open, and his tie half-undone. Scharr shot the man an nasty look and proceeded towards Hoffman’s desk. Despite his Luftwaffe uniform, Hoffmann was a civilian technician. That, for some obscure reason, the brass had decided to allow these technicians to wear Luftwaffe uniforms was to Scharr a source of constant annoyance. That it was an order didn’t make it any righter for the graying NCO. There was no way Johannes Scharr, Great War and Freikorps veteran that he was, would ever address the likes of Hoffman as fellow soldiers, and he winced any time one of those civilian ‘experts’ tried to throw around some military lingo to sound like “one of the boys”.

“What is it, Hoffmann?”

“Stabsfeldwebel, I found a match. One of the numbers we were asked to monitor closely last month. You know, when that guy from the Tirpitzüf-”

“Let me see that” interrupted Scharr, snatching the paper from Hoffmann’s extended hand. It was a single page, typed on a regular yellow form. On the upper-left corner, the Luftwaffe eagle seemed to be perched on the letters ‘RLM/FA – GHM+’. For the non-initiated, this was just another meaningless acronym for just another faceless cog of the German bureaucratic machine. For the eighty employees of the Schillerstrasse, that meant this was a most secret document belonging to the Research Office of the Air Ministry. While the appellation could have suggested some kind of aviation-related stuff, the Research Office cared precious little about warplanes and great silvery birds. Uncharacteristically for a supposedly Air Ministry office (and even that was deceitful), it mostly dealt with underground matters: telecommunications cables, and how to access them. Created at the behest of Hermann Goering, then head of the Gestapo, the Forschungsamt was the world’s biggest and most successful wiretapping operation ever launched by a State to control its citizens. In Berlin alone, tens of thousands of targets were wiretapped round the clock, with many more across the whole Reich: army officers, industrialists, diplomats, journalists, artists, foreigners, priests, even Nazi officials were monitored. Every single embassy was, for the Forschungsamt experts, a glass house when it came to phone calls and teletypes.

While this gave the Nazi regime a considerable advantage over its local opposition and made espionage in Berlin a very risky proposition, it was far from making the Research Office omniscient, or omnipotent. As it happened, the sheer size of the operation greatly limited the Research Office’s ability to act upon the information it collected. Despite the automatization of the filing system, made possible through the acquisition of several American-made tabulators from International Business Machines, the amount of information that had to be treated, cross-referenced and updated before it could be exploited was staggering. With the exception of certain targets that were given top priority 24/7, the Forschungsamt analysts usually needed weeks, to type and analyze all the transcripts the wiretaps generated. With so many targets, any change of priorities caused within days a colossal backlog of unprocessed transcripts that took its harrowed analysts weeks to finally clear off. And that explained why Hoffmann’s prized transcript actually dated from May the 10th.

“The transcript’s quite short” remarked Hoffmann. That, Scharr saw, was quite an understatement. Four simple lines in pale blueish ink – the secretaries always complained about lack of new typing tape - that went :

“Caller : We just had news from our cousin. He’s on duty tonight.

Receiver : Perfect. Anything out of the ordinary?

Caller : No, nothing. His uncle is already on his way.

Receiver: Then we’re just going to have to wait”

“The caller’s ID, it’s one of the numbers the Tirpitzüfer guys signaled” repeated Hoffmann, as Scharr checked on the small notepad where he jotted down the current priority targets’ references. Hoffman was right, he saw. Caller #789621 had been given priority after a request from one of the Forschungsamt’s Abwehr contacts. As a matter of ‘professional courtesy’, the officer had said, which was the accepted way of saying “please don’t tell anyone else”.

“Have you checked the caller’s identity?” demanded Scharr. The brevity of the conversation troubled him.

“I have” said Hoffmann with a shrug. “Registered as one Fraü Helga Kirsch. Her file card says war widow, aged seventy-three, Catholic. No political activity mentioned. Address is mentioned as a one-room flat in 19, Gutenbergstrasse. That’s Dahlem. The Abwehr goes after elderly church-goers now?”

Scharr only dignified the question with a grunt. Maybe the Abwehr officer had mixed up numbers somehow – in which case, the only sensible option was to signal the mistake, and reassign Hoffmann to the mounting backlog of unread transcripts for the time being. Man/hours were too precious a resource to waste on wild goose chases. Still, it was curious that a wrong number would still appear in the files. Even in a city of four million people, Scharr considered, the odds for that to happen were – well, they were pretty slim. And the conversation was definitely odd. Way too short. Not even a full minute. No hellos, no “Heil Hitlers”, no small talk, no nothing. Straight to the point, and yet, pointless. Vague. Scharr didn’t like that. Normal people never talked like that. Hell, not even criminals talked like that.

“There’s also that thing, with the receiver’s ID” added Hoffmann, shaking Scharr out of his thoughts.

“What of it?” asked Scharr, still mulling the content of the transcript.

“It begins with a letter” said Hoffman. “First time I see one like that”

“What?” blurted Scharr, squinting to make out the number. And here it was, to his shock: X540977.

The NCO felt a shiver running down his spine. Letter-coded identity numbers were only attributed to high-profile, official targets. That was bad news enough. And worse yet, Scharr was pretty sure he knew that X-series number.

“Have you identified that receiver ID before?”

“Er, no” said Hoffmann. “That’s the thing – there’s no card in the file for that number”

“Get the tape” snapped Scharr. “Get the tape now, and bring it to me in Major Plassner’s office. In person.”

Thirty minutes later, Hoffman dismissed, Scharr flicked off the magnetophone that occupied a solid half of his desk. He and Plassner had played the magnetic tape three times, just to be sure. But there was no doubt to be had. Unless the mysterious Frau Kirsch had died and come back as a man in his thirties, there was no way the call had been placed by an elderly widow.

“What do you make of that ‘Frau Kirsch’ business?” asked Plassner. “

“It has to be a relay, a safehouse of sorts. For some reason the Abwehr knew about it.”

“Makes sense. And you confirm the receiving number is….”

“It’s an Albrecht number, sir” said Scharr, using the Berliners’ nickname for the Prinz Albrechtstrasse, one of the most-feared addresses of Berlin as it housed part of the SS. “I’m positive. I double-checked it with our unofficial ‘black list’ while Hoffmann collected the tape. When we tracked it a few years ago, it was assigned to the Albrecht’s Bureau IV, Section B.”

“You know what that means” stated Plassner, toying with a lighter. “Supposing the number has not been reassigned”.

“Yes, sir. It’s the Sicherheitsdienst’s foreign operations bureau, sir” replied Scharr.

“Correct, Scharr. That’s Walter Schellenberg’s outfit. The number three man of the SD, no less. And the call came through shortly before the Paris attacks that the Abwehr is so keen to elucidate”.

“About an hour before, sir. Herr Hauptmann, what do you want us to do now? Shall we alert the Abwehr about it?”

“What? Certainly not” replied Plassner. “Not a word, not to the Abwehr, not to anybody, until we clarify the situation.”

“Very well sir. Will you notify the Director?”

“Oh no” replied Plassner. “For one thing, I’ll remind you that our blue-blood director belongs to the SS. Until we know exactly in what we have just stepped in, I am not going to tell him that you, me and Hoffmann over there have tangible evidence that his friends and patrons at the SS’ Security Office might have planned an assassination attempt on a foreign head of state. And neither will you, unless you want to be found dead in some seedy hotel like poor Dr Schimpf.”

“No sir” said Scharr, who knew the story all too well.

“Sehr gut” said Plassner. “I also find it disquieting that the receiver’s ID card has been removed from the reference files. If we didn’t keep our own ledgers, we’d still be in the dark about that Albrecht number. Someone in this office has tried to muddy the water around that number Scharr. It’s not me, and obviously it’s neither you nor Hoffmann.”

“It cannot be someone who has access to the black list or the calculator’s central file either” added Scharr. “With that kind of access, they’d have either changed that ID to a low-priority code, or erased it altogether.”

“Same goes for the technicians, they’d have disconnected the wiretap. So that leaves the analysts and secretaries. Our own colleagues, dammit! There’s someone just beyond that door who is not who he seems, Scharr. There’s someone out there who does not work for us.”

“Yes sir” confirmed Scharr. “What do you want me to do ?”

“First of all, have Hoffmann comb the backlog for other messages coming from or to either one of these numbers. No one else but Hoffmann. Impress upon him that it would be in his best interest, not to mention yours and mine, to keep his mouth firmly shut about the whole thing. Any information goes to me directly, and to me alone.”

As Scharr closed the door behind him, Plassner lit a cigarette to calm his nerves, cursing silently at Hoffmann, Scharr, Director Prinz von Hesse, as well at himself. As incredible as it seemed, Plassner thought, it actually was possible to be killed by bullets shot a whole month before, hundred miles away. Another German miracle! To make things worse, his staff was compromised - apart from Scharr, who was reliable, the only person he could be sure of was a wet-behind-the-ears low-level analyst. If Plassner wanted to dodge that Parisian bullet, and he sure did, he’d have to play his cards exactly right. The first thing was to find some protection against the Gestapo. That left him with but one option. Forcing himself into a composed posture, Plassner picked up his phone – he had little doubt it, too, was tapped - and composed a number.

“The Reich’s Air Ministry please” he said to the operator when she asked where he wanted to place the call. “Field-Marshall’s Goering personal secretariat for Hauptmann Plassner. Of the Schillenstrasse.”

In the end, Plassner thought, we all run back to daddy.

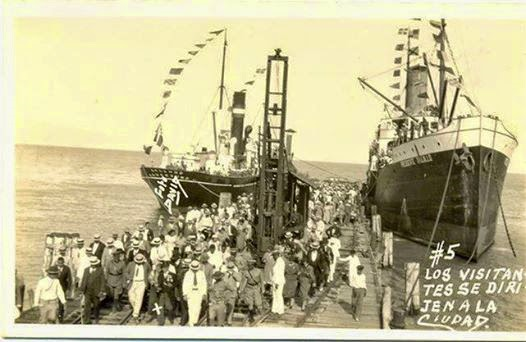

Ciudad Trujillo, August the 17th, 1939

Preston Miller and his companion walked through the crowded streets that radiated from the seaport. The street was particularly busy that day, forcing them to elbow their way past dozens of peddlers and money-changers, converging towards the Santo Domingo Terminal where the St Louis, a German ocean liner from the Hamburg-Amerika line, was about to moor amidst a clamor of bullhorns. From where he stood, Miller could see the gleam of the morning sun on the copper instruments of a welcoming band. The morning papers had been full of the story of the Havana-bound liner's odyssey, whose passagers, mostly German Jewish emigrants, had been denied access to Cuban soil despite the visas that had been delivered to them. As the St Louis had then steamed towards the American coast, the crisis had soon grown international, as Earl Long, the governor of Louisiana, had made it know that he'd regard the debarkation of the passengers as sanctioning illegal immigration by and oppose it by any means necessary, a position that soon struck an echo with other Dixie Democrat legislatures, but also with some in Lindbergh's America First Committee and even within the Landon administration, where some, like Taft, urged the President not to alienate the Dixiecrats who would prove necessary to divide Democratic votes in the coming 1940 elections. In the end, State Secretary Knox, seconded by the French and British governments, so all Cuba-bound emigrants would be given visas to the Dominican Republic, while the others would be offered residence in Britain, France and Italy.

“What a travesty” grimaced Miller's companion, as they passed before a crude poster proclaiming 'Santo Domingo welcomes you to your new homeland', under the smiling face of President Jacinto Peynado.

German refugees disembark at the Santo Domingo terminal

“Good business sense, though, Mr Daenecker”, replied Miller. “If they keep it up, Trujillo and his patsies will be the darlings of most Western governments. I have heard the Dominican government has struck a deal with some lines to propose complete 'cruise-and-visa' packages. They haven't approached the HAPAG yet?”

“I have no idea” grumbled Daenecker, blushing, as Miller smirked. As both men well knew, the Hamburg-Amerika line, HAPAG for short, already had its thumb in that juicy 'emigration cruise' pie. Not that it was alone: all over Europe, dozens of “freedom networks” were already operating, offering to evacuate those who had something to fear from the German government, from Czechs to Jews to Jehovah Witnesses. But that was none of Miller's concerns, at least, not for now.

“I think I see them” said Daenecker, tugging at Miller's elbow as he pointed at a small group, enjoying fresh cerveza under a line of palm trees.

“Don't point” said Miller, pushing his companion's arm down and pushing him in the direction of the café. “It's neither polite nor discreet”

As Miller and his associate approached, the three men made room for the newcomers. The beer-drinkers, Miller noted, denoted in the tanned multitude of the city. Two of them looked pale as death, while the third one, with its bright red complexion, evoked some half-baked lobster. Their attire – wool sweaters with rolled-up sleeves and crumpled shirts of a dubious grayish colour - also seemed out of touch with their surroundings, but Miller hadn’t expected much in terms of alluring clothes.

“Meine Herren”, said Miller, tugging the brim of his panama as he sat down. “Thanks for your patience”.

“We were supposed to meet last night” said the lobster man gruffly.

“Indeed, we were” replied Miller, waving at a passing waiter. “But last night our good friend here didn’t have what you required.”

The red-faced man and his companions kept silent while the waiter renewed their drinks and brought the newcomers’ order. From the port’s terminal, the faint echoes of a badly played ‘Deutschland, Deutschland über alles’ reached them over the rumors of the city.

“Can’t believe they’re playing them that” sneered one of the pale men, shaking softly in head in disbelief as he identified the hymn. Obviously the sullen trio had learned about the nature of the St Louis’ voyage.

“A pity they came ashore so soon” added the rubicund man. “A few weeks later and I’d gladly have sunk the damn ship.”

“It’s a HAPAG ship!” hissed Daenecker, spilling half of his cerveza as he brutally put his glass down. “Are you out of your mind?”

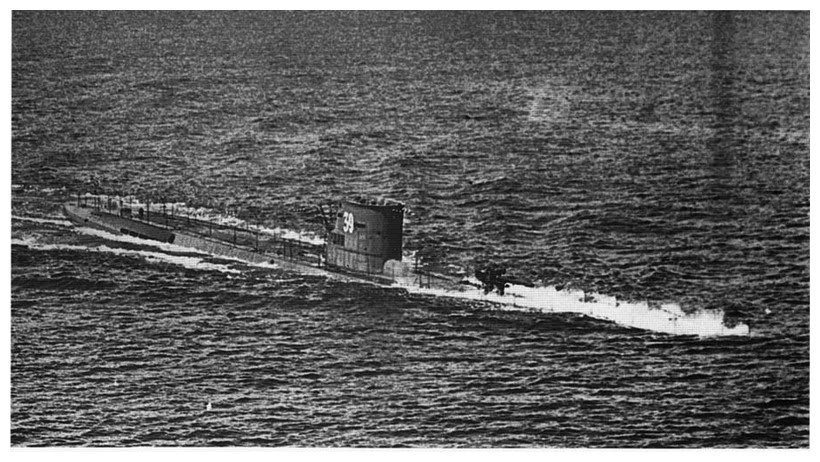

“I think” said Miller with authority, “that it would be best if we kept this meeting as short as possible. As our friend here has pointed out, we’re already behind schedule and you’ll need to get back to your boats as soon as the sun sets.”

“We should already be there” grumbled the lobster-faced one.

“Oh, I am sure you’ll find some way to pass the time around here” said Miller. “This city is quite renowned for its various forms of, ah, entertainment, you know. Though I would not recommend it. A hangover or a bad case of the claps are best nursed ashore, I have been told. Unless the comfort has greatly improved in those pilchards cans of yours, of course. Are you ready to listen to Mr Daenecker now? Because I, too, have many things to do today, as it happens. Great.”

Nudged by Miller, a still-skulking Daenecker fished into the leather briefcase he’d put between his feet and produced several wads of paper. They were about half-an-inch thick, each page covered in types characters neatly organized in five columns. The first one listed names, the second one ports, the third ones dates. The last two columns listed other ports and dates.

“There you have it” said Miller, in a lightly-accentuated German. “Courtesy of my employers. The planned maritime traffic that will cross that part of the Caribbean in the next two months. Freighters, tramps, tankers, the works. The ones underlined are supposed to bring strategic cargo – military supplies, locomotives, machine-tools and other crucial supplies. That should give you a solid advantage in the fist weeks of a conflict.”

Daenecker fidgeted. He felt terribly out of place sitting in that café, in the middle of that clandestine group, and he longed after his comfortable office of the barrio alto. Above all, he wanted to walk away from Miller. Despite the American’s apparent affability and business-like manners, just being in his company felt wrong. The man had an air of quiet malevolence about him that frightened the Hell out of Daenecker: it was all too easy to imagine the American hiring some street thugs to silence him on his way home. Come to think of it – and the HAPAG employee was discovering this was a thought that came very easily after a mere few hours in Miller’s company – it was even easier to picture the American doing it himself. But Daenecker had had no choice in the matter. The men Miller spoke for – the ‘Majestic Group’ as they apparently called themselves – were not the kind of people who took no for an answer. They had the kind of clout that the HAPAG board of directors could only dream of.

“What do your employers gain from it?” asked the third man, who had hitherto remained silent.

“Less than your Fatherland will” replied Miller with a quiet smile. “Our agreement with your superiors is that you will concentrate on these ships for the first months, and will not attack any other merchantmen. As long as it is the case, we will provide you with information to help pin-point these ships’ position as they reach each of their way points. So, you see, there’d be no point in looking for other... prey.”

“Like your employer’s own freighters” concluded the third man, not even bothering to make his statement sound like a question. Again, Miller simply smiled.

“Why look into a given horse’s mouth?” he asked. “There’s enough tonnage in these few pages to earn you a gold-plated Iron Cross, or whatever trinket is in fashion in Berlin.”

“I’d better get going” said the pale man. “Tell the pick-up people they’d better not leave without me tonight”.

Tucking the wad of paper under his belt, Korvettekapitän Glattes stood up and left without a last word. The three submarine groups had received their targets. If, as it now seemed probable, war broke out in the coming weeks, they and twelve other U-boot would wreak havoc on Anglo-French shipping. All it would take would be a simple signal, which would be emitted by the Kriegsmarine’s powerful radio stations, and repeated by various transmitters established in America by the German-American Bund. In the meanwhile, the submarines would take their war positions and monitor the sealanes. They’d be regularly resupplied, either through a series of depots set up in discreet areas – Glattes’ own depot was almost a stone’s throw away, on a small cay a little off the Beata island – or at sea, with the help of three tenders which were already present in the area. In a few hours, unde the cover of the night, a small launch would take Glattes back to his boat, and no doubt similar arrangements had been made for his two colleagues. All Glattes could think of now was the fact he’d soon feel the bridge of the U-39 under his feet, and smell its familiar stench of unshaven bodies and grease.

After that morning’s meeting, Glattes mused, even an hour in the reeking submarine’s privy would feel like a cleansing ritual.

Game effects :

We just had the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, obviously. And the German naval OOB has been beefed up a bit, as Plan Z got updated a few letters.

Writer’s notes :

The first part of the update is my not-so clever way of integrating the changes I made to the German naval OOB, as well as an attempt to explain the extreme variations through which each of my reboots subjected Romania. In OTL the French embassy in Moscow was vacated for a few months, as the Vichy ambassador was expelled after Barbarossa, and Free France was only allowed to have a special envoy in 1942 (not sure he used the embassy though). In this ATL the old Franco-Russian friendship has not survived France’s militant anticommunism and its Spanish intervention to bring down Soviet Spain. Faced with anticommunist France, anticommunist Britain and anticommunist Germany, Stalin has decided to deal with the one who can pay the dearest price, and that is the Reich. So von Brickendrop is alone in Moscow, while in OTL there was a competing Franco-British team that tried to seal a deal with Stalin. That did not go well (among other things, the British envoys, which included my all-time favourite naval officer, the improbably-named Admiral sir Reginald Aylmer Ranfurly Plunkett-Ernle-Erle Drax, had no powers to negotiate anything specific, and the Soviets were reportedly unimpressed with Britain’s small number (6) of ready-to-deploy divisions in case of war). Of course, the dictator of the Kremlin had probably already decided that siding with Germany meant possible territorial gains, while siding with the democracies meant a territorial status quo.

Martin Luther we briefly met years ago, negotiating with the Polish FM. The man was one of von Brickendrop’s top aides, and, true to the spirit of camaraderie that prevailed in Nazi Germany, eventually tried to oust his boss to take his place. It didn’t work, and the good Dr Luther was sent by von R to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp (because, again : camaraderie). We’ll shed no tears for him though: during his stint at the Foreign Ministry Luther blackmailed people, misused public funds, and among other niceties participated to the infamous Wannsee Conference (though some think he did not fully understood what was discussed). Rather regrettably, he died from natural causes shortly after VE-Day, as it appeared he had a weak heart (colour me surprised that he had one altogether). I am sure Molotov would have loved facing the likes of Luther in all the important negotiations.

Otto Rahn was a real character. He did write two books about the Holy Grail in 1933 and 1937, after extensive research in France where he befriended some regional historians and amateurs of the occult. His OTL background was as described here, with the glaring exception that, at the best of my knowledge, he never met Abetz (and of course never engaged in a romantic relationship with him). I was surprised, when I started writing this chapter, by the coincidences between Rahn and Abetz, and I liked the idea of associating the two Ottos more intimately as Rahn was quite openly homosexual (a risky proposition in the SS where one could incur article 175 of the German Reich’s Penal code). Rahn joined the Black Corps without enthusiasm (“A man has to eat” was the explanation he gave in a letter to a friend). After a short period of favour (Himmler really had Rahn join his personal staff after the publication of his first book), Rahn attracted the attention of the Gestapo. He died, OTL, in the spring of 1939, officially from exposure while mountaineering in the Austrian Tyrol. Some think it was suicide – Rahn was indeed pretty depressed, as war loomed and some of his friends had been arrested. In another letter, he hinted at (and lamented) crimes committed by the Nazis. Others think he was executed by the Gestapo, possibly for his homosexuality, possibly for other reasons. For further reading on his life and work, I recommend Christian Bernadac’s The Otto Rahn mystery.

The Solhlberg Franco-German Youth Meeting was an annual congress of both countries’ youth organizations, aimed at fostering friendship across the Rhine and prevent another Franco-German war. Abetz really did head the thing, and it seems his Pacifist stance was sincere.

Vitaborn was a popular German brand of bottled juice in the 1930s. The company that bottled it was an integral part of the SS economic empire, and Vitaborn soft drinks were a usual gift among the SS.

The Director of the Forschungsamt was, from 1935 to 1943, Prinz Christof von Hesse, of German royalty and therefore also, amusingly, a member of the extended British Royal Family as he was the Prince Consort’s brother-in-law if I get it correctly. Boy, those family dinners at Balmoral must have been a riot. Under his directorship, the Research Office is supposed to have developed close ties with the SD, but nobody said it was all done in the open.

Dr Hans Schimpf was a very high-ranking officer of the Forschungsamt who met an untimely death in 1935, when he was found “suicided” in a hotel in Grünewald, on Goering’s wedding day no less. Speculation is that he had been killed by the SD, after he had refused to work for Heydrich and betray Research Office founder Hermann Goering. Days later, SS-member Prinz von Hesse took control of the Forschungsamt. Another theory, though, is that Goering ordered the murder himself, as Schimpf knew too much. Regardless of which theory is correct, one can imagine the level of bad blood this must have (perhaps quite literally) left within FA ranks. Talk about taking office grudges seriously!

Ciudad Trujillo was the name given, in 1936, to the Dominican capital of Ciudad Domingo. Accordingly, the country’s highest peak was renamed Peak Trujillo, and one of the country’s provinces also became the Trujillo Province. Any link with the fact the country’s dictator was then named Rafael Trujillo was a complete coincidence. ‘God and Trujillo’ was the country’s motto, and a semi-official prayer began with “God in Heaven, and Trujillo on Earth”. Trujillo reigned thirty years, either directly or through puppets like Peynado, and was killed in 1961 before he could decide to have the Trujillo Sea, the Trujillo Triangle or the Trujillosphere.

The St Louis was a liner from the HAPAG that, in the summer of OTL 1939, embarked on a dreadful voyage. Full of German Jewish refugees, it was denied access to La Havana where many of its passengers were supposed to disembark, as Cuba’s immigration laws had changed. Access was also denied to the United States (Dixie Democrats threatened to torpedo Roosevelt’s reelection chances in 1940), and Canada. In the end, the liner, still with most of its passengers, went back to Europe where France, Britain, Belgium, among others, granted asylum to the hapless refugees. Trujillo’s Dominican Republic didn’t play a big role in the St Louis’ affair, but the country did welcome many German Jews during the late 1930s (some say as a way of making nice after having engineered a racial massacre of its own against Haitians). HAPAG really did offer “cruise and visa” packages when it was realized Cuba’s immigration laws had been written in a confusing way and gave considerable leeway for rebranding refugees as tourists.

Moscow, July the 10th, 1939

So, thought Ribbentrop pleasantly, as the two delegations entered the vast meeting room, that’s where they want us to work today. Excellent !

In itself, the room had nothing remarkable. It was a long rectangle, occupied at its center by a large dining table covered in green felt, with two rows of chairs. On each side, another row of chairs was aligned against the wall. The walls were dark green, adorned with a few paintings, mostly of Western European landscapes. On the right-side wall, two darker squares betrayed the recent removal of two frames – official portraits, no doubt. The room had been cleaned by their hosts, who had made a point of leaving the rest of the building untouched. The Soviet officials had guided the German delegates through a series of halls, offices and corridors which looked like they had been abandoned in a hurry – which, Ribbentrop thought, was probably the case. In the offices, the desks and chairs were askew as if the offices’ occupants had been ordered to leave at gunpoint, and the corridors leading to the meeting room were littered with sheets of papers that sometimes took flight when one opened the double doors, briefly lifted by a draft coming from a broken window pane. One type-written page flew past the German Foreign Minister, who snatched it mid-flight and examined it briefly. His fluency in French was next to non-existent, but he recognized the words “Paris” and “Staline” .

With a wan smile directed at his Soviet counterpart, Ribbentrop looked up and made a great show of crumpling the paper in his gloved hand and tossing it aside.

“Meaningless drivel” he said. “Empty promises.”

Moscow’s Khodynka airport, where the German delegation arrived

Across the table, Vyatcheslav Molotov, the People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs, nodded with an affable smile. This talks with the German delegation was of capital importance for the Politburo, and therefore for him personally, and he thus congratulated himself for having picked the place for the meeting. Not that it had been much of a challenge, as Molotov and his aides had had ample time to decipher Ribbentrop during previous encounters. The man could be summed up in one word : vanity. Watching the German strut around what had once been the French embassy to the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, Molotov mused, one could think Ribbentrop had conquered it himself. Such, Molotov knew, was Ribbentrop, and in many ways such was the regime he represented : brutal whenever it was without risk, blustering when it faced resistance, narcissistic in the extreme at all times.

Yet, the Russian reminded himself, the road to the Revolution in Europe once again leads through Germany.

“Shall we begin?” proposed Molotov, inviting the delegates to take their seats, in front of which water jugs and notepads had been placed. He refrained a sarcastic smile as Ribbentrop took off his cap in a flurry, throwing inside a pair of gray felt gloves. Who wore gloves in July?

“I understand”, began Ribbentrop, “that the Soviet government has expressed his readiness to take our partnership to a new, unprecedented level. I am authorized by the Führer himself to conduct any negotiation between our two countries relative to reaching a wider agreement.”

“And I have been instructed by the Politburo, and by First Secretary Stalin personally, to lead our discussions” said Molotov, as German and Soviet aides traded their letters of credentials, making sure both sides were on the same page.

“The past year has shown there were many points of convergence between our two nations” stated Ribbentrop. “I think it is in our mutual interest, as the two strongest powers on the continent, to pave the way for a global agreement that would encompass all areas of possible cooperation and put to rest any risk of misunderstanding or mistrust.”

“Where better to initiate this new era of mutual understanding than in this building ?” said Molotov. “Both our nations face the hostility of the so-called Western democracies. Both our regimes have made the destruction of the bourgeoisie their priority, be that within our borders or...without.”

Ribbentrop smiled at the implication, as German delegates rapidly shared looks. If Molotov really was proposing what they thought, the Wilhemstrasse – and, of course, every one of them - was on the verge of scoring a major political success.

Well, another one in just two years, thought Ribbentrop.

“Does that mean the Soviet government stands ready to discuss matter of… territorial importance?” asked Martin Luther, second-in-command of the German delegation. The security officers attached to Molotov’s staff had compiled a file on this German as well. The portrait they had drawn of Luther was hardly flattering : a toadie, mimicking his boss’ worst traits while having none of its few qualities. While Ribbentrop could be cunning at times, Luther was a ham-fisted brute. And while Ribbentrop had shown earlier he was ready to take some personal risks in pursuing his objectives, Luther emerged as a complete yes-man, mostly preoccupied by currying favour with more powerful party bonzen. This mix of ambition and average intelligence made him, in the Soviet official’s eyes, a most welcome addition to the German delegation.

“The Politburo is of the opinion that we both stand to gain from a bilateral agreement regarding our respective zones of political influence” acquiesced Molotov. “Comrade Stalin sees such an agreement as the logical next step after the economic agreements of the past few months.”

This time, the traded looks on the German side lasted longer.

The rapid deterioration of diplomatic relations between the French Republic and the USSR, and their interruption after the fall of the Spanish Soviet Republic, had been too good an opportunity to pass for Germany. After six years of uneasy coexistence between the Reich and its Eastern rival, the Wilhelmstrasse had immediately reactivated the old influence networks of the 1920s, and German feelers had been extended through third-party nations. At first, the German overtures had been received cooly by the Kremlin. Some Politburo members like Maxim Litvinov, Molotov’s predecessor, had been reserved, if not open hostile, to the idea of a détente with Nazi Germany. Wasn’t Hitler the champion of anti-communism ? Wasn’t the German Reich actively pushing for an anti-Komintern Pact in Asia and Europe ? Weren’t German communists sent to camps by the hundreds, when they were not killed in the streets by the Nazi Stormtroopers ? Others, notably among the junior members and candidates, had been more receptive, sensing this détente could serve their own personal ambitions. The Nazi regime, they said, was not like the bourgeois democracies of the West. It had been opportunistic, harnessing revlutionary forces which might one day escape their control. Couldn’t the USSR hear the Germans out, and see if there was something to be gained for the Soviet regime ? If there wasn’t, the contacts would be broken off, and that would be that. The debate had continued throughout most of 1936, both sides discreetly encouraged by Stalin. As he often did, the master of the Kremlin had waited until both sides were fully committed before showing his hand. He finally spoke on the 5th of january, 1937, during an extraordinary session of the Political Bureau. Nazi Germany, he had finally said, assuredly was a despicable imitation of a Socialist state, mimicking revolutionary fervour but ultimately serving the interest of the petty bourgeoisie as well as of capitalists. As such, though, it constituted a decaying form of bourgeois State, which would only precipitate the destruction of the so-called “democratic” forces and pave the way, ultimately, to a true Marxist revolution that could take the whole of Europe with it. Therefore, any deals with the German Reich would only give it temporary advantages, readily consumed, like crude oil, wheat and ores, while they could allow the Soviet Union to acquire much-needed advanced technical know-how and could even lead to permanent gains in eastern Europe. A true Socialist approach, Stalin said, would thus be to welcome Hitler’s openings with open arms, and get ready to rob him blind. On January the 6th, the Politburo voted unanimously to engage in discreet negotiations with the German Reich. The next day, the Izvestia newspaper announced a partial reorganization of the Politburo: the aging Maxim Litvinov and two of his staunchest partisans had stepped down, temporarily and at their own request of course, on grounds of ill health after years of exhausting work on service of the People. The formulation of the announcement had not fooled the Wilhelmstrasse’s ‘Kremlin experts’: Litvinov was in disgrace, and his dismissal cleared the path for diplomatic progress with the Soviets. Berlin had sent a congratulations telegram to the new Foreign Minister, Vyatcheslav Molotov, and had waited with baited breath for another signal from Moscow. It was not long in coming : on May the 9th, the Soviet ambassador to the Reich had sent a request for an appointment with Ribbentrop : would the Reich’s Foreign Minister be interested in exploratory talks on subjects of interest for both nations ? Three weeks later, the talks were in full swing, broaching a wide range of topics from oil sales to technology transfers, as well as the discreet set-up of German arms firm subsidiaries in Soviet Russia. The partnership, which was hailed in Berlin as a new Rapallo, made the delight of the OKW : safely hidden from Western sight, German-operated plants were manufacturing artillery tubes and small ammunition, German tanks were tested on Red Army bases, as were Messerschmidt and Junkers planes. At the Leningrad shipyards, more than a dozen submarines were being assembled, and welders were working three shifts, under the watchful eyes of KGB sentries, to prepare the launch of the Kriegsmarine’s second aircraft carrier. In Germany itself, the economic accords ensured the continued flow of crude oil, chrome and manganese which the Reich’s heavy industry direly needed. In return, German trains and freighters left for Russia every week or so, either delivering machine-tools and manufactured goods or debarking German engineers and technicians, ready to build new factories in the Soviets’ country.

The two delegations arrive at the old French embassy

“Both our nations have vested interests in the Baltic” stated Ribbentrop. “As well as in the Balkans of course.”

“Which only emphasizes the importance of reaching a general agreement”, Molotov approved with a nod. “This is why the Soviet government seeks an all-encompassing pact, ranging from the Gulf of Finland to the shores of the Black Sea, and providing clear guidelines to coordinate our diplomatic efforts in third-party nations.”