BipBapBop/

yourworstnightm: Maybe, maybe not.

History_Buff

History_Buff: The idea of military access always struck me as a bit cheap, and I'm not exactly on the best of terms with the Portuguese right now. As for Italy, the Navy doesn't really have much of a presence in the Mediterranean, and seems like it could be a huge risk if the Syndicalists made a concerted push to retake Gibraltar.

Parokki: Well, with what France is throwing into Iberia, who knows how long it'll take for Bradley to get to the Pyrenees.

naggy: Ah, but that would be lame.

Viden

Viden: Bah! You just want the Syndicalists to win, don't you!

-----

1945 - Part III

On June 23, 1945, a group of scientists and military personnel arrived at the desolate, uninhabited area of New Mexico approximately seventy-five miles south of Albuquerque. For several days prior, the surrounding area had been sealed off by the Army as a small construction project, including a system of bunkers, trench lines, and a 100-foot steel tower, neared completion. The scientists and army engineers worked throughout the day, both hopeful and apprehensive at the culmination of the great experiment they had invested years of time and resources into seeing completed. Work continued well into the night, and it was only at 5:00 in the morning, after receiving favorable weather reports, that the Army gave the go-ahead for the experiment.

At 5:49 am local time, on June 24, 1945, an explosion with the force of approximately 21 kilotons of TNT erupted from the desert landscape. For an instant, the explosion burned brighter than the sun itself and sent a shockwave that could be felt over 100 miles away. Within minutes, a mushroom-shaped cloud formed, ultimately reaching a height of almost 8 miles. The United States of American had just detonated the first atomic bomb.

The world enters the Atomic Age.

The June 24 test was the culmination of a long, arduous process that began many years prior halfway across the globe. The field of nuclear physics was a young science, dating little earlier than the close of the 19th Century. Germany, eager to earn its place in the sun, had quickly become one of the preeminent scientific nations. One such expression of this goal of scientific and scholarly competition with the older European powers was the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute, founded by Wilhelm II. Although the Kaiser's support for the sciences did not waver following the devastating Great war, the German scientific community began to decline during the 1920's, a trend only accelerated under the Tirpitz chancellorship; German universities had long depended upon generous money grants from private sources. After the Great War, which nearly saw the whole of Germany starve to death under the British blockade, the source dried up, threatening countless professorships. Worse still, a new generation of leaders, many of them Great War veterans, turned their backs on the sciences, ignoring the invaluable contributions scientists and engineers made for the German victory in the war.

Consequently, many 'old guard' physicists, particularly those that objected to Einstein's theory of relativity, began to fight desperately to retain their university seats in the face of funding shortfalls and a glut of physicists. Spearheaded by Philipp Lenard and Johannes Stark, the so-called '

Deutsche Physik' movement emerged, quickly tapping into many strands of latent anti-Semitism within the German Empire. Many scientists, notably Albert Einstein, chose to emigrate rather than endure these assaults on their academic integrity.

In spite of these developments, German physicists continued to make many landmark discoveries. One such discovery was made in early 1938 by Otto Hahn, working in cooperation with Lise Meitner and Fritz Strassmann, who successfully demonstrated the existence of nuclear fission. However, with France inching ever closer to war and Germany still suffering from the Berlin Stock Market Crash of '36, little time or effort was spent on expanding on Hahn's results. That is, until Leo Szilard. Just after the outbreak of war in 1940, Szilard wrote to Niels Bohr, the pre-eminent physicist of the age, offering up his thoughts on Hahn's discovery. Inspired by H.G. Wells' writings, Szilard envisioned the development of nuclear power. Bohr reacted favorably to Szilard's thoughts on this potentially revolutionary development, but expressed doubts as to the practicality of nuclear fission.

Szilard, frustrated in his attempts to gain any support for his ideas from the Austro-Hungarian government, already paralyzed by the joint fear of French and Romanian invasion, turned next to Italian physicist Enrico Fermi, who fled the Italian Federation to the United States when it became clear that the Syndicalist alliance would inevitably invade. Fermi, who had made many contacts and acquaintances in his short time in the United States, listened to Szilard's ideas with great interest and, in the spirit of the free and open exchange of information in the sciences, disseminated Szilard's ideas.

It was in this way that Hungarian expatriate and physicist Edward Teller and Vannevar Bush, head of President Roosevelt’s new National Research Committee on Defense came into contact with one another. Bush, chairman of the new committee since its creation in 1940, had made great efforts to gain the support and cooperation of several esteemed scientists, including Arthur Compton, James Conant, and Ernest Lawrence for practical applications of the recent developments in nuclear physics. Teller, much to the chagrin of both Fermi and Szilard, suggested to Bush the feasibility of nuclear weaponry. Bush, for his part, embraced both possibilities and went directly to Roosevelt with the proposal of a federally-funded project in March of 1941.

Not surprisingly, the details were quite beyond the President, but Roosevelt nevertheless expressed interest in Bush's suggestions. Issues of not only cost, but whether or not either nuclear power or weaponry was even feasible were swept aside by the prospect of providing a massive boost to American academia, which had suffered significant disruption as a result of the depression and civil war, and help the economy with the inevitable private contracts the project would necessitate. But many physicists, despite the incentive of steady work and virtually limitless resources to conduct experiments, balked at the offer to work in this Manhattan Project, as it was soon to be dubbed as a matter of secrecy. It was this very secrecy that made many scientists turn away, accustomed as they were to working in an open environment in which sharing information and cooperation was axiomatic. Richard Feynman, one of the many who turned down the offer, later said, 'It was sometimes argued that we had to be the get this bomb, or else France, Britain, or even Germany might get to it first and use it against us. I thought then, and I know now, that it just wasn't the right thing to do, to help create that kind of monster. We were the only ones even thinking about bombs.'

Some found the offer too good to resist: Fermi, despite his misgivings, agreed to continue his work on a nuclear reactor in conjunction with the Physics Department of Harvard University. Robert Oppenheimer of the University of California-Berkeley, too, joined the Project, quickly becoming its scientific director. Despite recruitment efforts by Bush, both Einstein and Bohr, who fled to the United States with his family following the fall of Denmark, retained only consulting positions.

Oppenheimer and the Project's scientists quickly went to work on the question of a nuclear weapon. After some theoretical experimentation, it was eventually concluded that only the rare U-235 isotope or plutonium, by-product of the fission of U-238 discovered at Berkeley. As a testament to the resources now available to the prospering United States, Oppenheimer and Army liaison Brigadier General Thomas Farrell recommended proceeding with the development of both alternatives, resulting in the construction of the massive isotope separation facility northwest of Twin Falls, Idaho on the Snake River and an experimental nuclear reactor, derived from the first successful nuclear chain reaction by Fermi's team at Harvard, at Los Alamos, New Mexico.

Having overcome the major obstacles in the quest for atomic energy, the question rapidly shifted toward one of implementation in 1944. With Germany conquered by France and virtually every notable physicist either beyond the grasp of France or working for the Manhattan Project, many scientists began to question the continued necessity of the project. Bohr, in particular, argued that the secret development of an atomic bomb, to say nothing of its use, would inevitably trigger an international arms race with terrible consequences. Einstein and Oppenheimer concurred, as did Vannevar Bush, but General Marshall and the President thought otherwise; vast amounts of money and resources had been poured into the Project, to such an extent that the Project had nearly been exposed to public scrutiny by then-Senator Truman's investigation of allegations of military waste and inefficiency in 1943.

The Manhattan Project as of April, 1945. The chief limitation remained acquiring useable material in sufficient quantity.

Undettered, Bohr sought to speak with the President directly. Having made little headway with Bush, the Danish physicist instead turned to a man who had only recently become closely involved with the Project, Secretary of War Henry Stimson, formerly Secretary of State in the Hoover Administration. Bohr impressed upon Stimson, in a meeting arranged by Bush in January 1945, the danger presented should the United States continue on its present nuclear policy. Always slow to come to a decision, Stimson spent a week deliberating, before ultimately agreeing with Bohr's perspective and arranging a meeting between Bohr and Roosevelt.

Soft-spoken almost to the point of muteness, Bohr cast an unimposing image for the President. Bohr argued that, given the destructive potential of these new weapons, using them would constitute the single greatest act of violence perpetrated in history, and inevitably prompt other nations to acquire these weapons. Bohr assured the President that the United States could not long maintain a nuclear monopoly, even if the Project was kept perfectly secret. Roosevelt listened politely but appeared unconvinced; to him, these weapons offered the possibility of shortening the war, and thereby imposing a peace on American terms that did not necessitate the massive loss of American life. Bohr responded by pointing out that countless innocents would inevitably die and, should the number of nuclear weapons proliferate, threaten the entire world.

Bohr left the meeting in a state of despondency. 'We didn't even speak the same language,' the physicist remarked shortly after the meeting. But the President had been struck by the sincerity of Bohr's argument, and conceded that, as a politician, he lacked the necessary scientific grounding to truly grasp the situation. At was at this point that Stimson made his fateful proposal: if and when the Manhattan Project bore fruit, the United States should inform the world of the new weapon and demonstrate its destructive potential, with the explicit threat that it would be used in the future should the Syndicalist alliance continue the war.

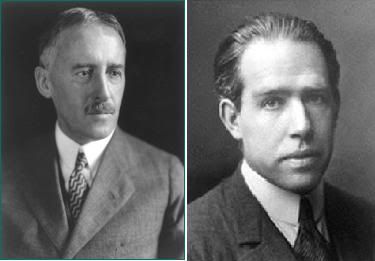

Henry Stimson and Niels Bohr, the two men who convinced Roosevelt to give France the choice to surrender.

Thus, when the Trinity test proved wildly successful, Stimson prepared to announce development of the first atomic bombs. But even at this late stage, Roosevelt was beginning to have second-thoughts. The Snake River facility, though operating at maximum capacity, had already produced enough U-235 for another bomb - which was already en route to Britain for deployment - the Los Alamos reactor was still far from producing enough plutonium, and stocks of uranium were rapidly dwindling. Oppenheimer and Farrell both reported that, at present capacity, the United States would not have a third bomb ready until mid-1946. Consequently, using 'Thin Man,' as the second bomb was called, as a demonstration of the consequences of further resistance would be little more than a bluff. But Stimson, in conjunction with Secretary of State Edward Stettinius, managed to convince Roosevelt to go ahead with the plan.

On June 26, 1945, the State Department informed all belligerent nations that 'the United States has recently acquired a new and terrible weapon of unprecedented destructive power.' Though the note gave few specific details, it stated, 'through recent advances in the field of nuclear physics pertaining to the process of atomic fission, vast quantities of energy greater than any conventional munitions is released.' To show the truth of these claims, the United States 'will detonate such a device in the skies above the English Channel, delivered by aircraft.' After warning the French and British to take necessary precautions in the event of tidal waves produced by the blast, the test date was set for July 1. 'Following the demonstration of this new weapon, the United States will grant all belligerent nations until July 7 to immediately sign an armistice with the United States.' The note outlined Roosevelt's terms: immediate cessation of hostilities between the Syndicalist coalition and the Entente and Hungary, disarmament of all French forces in Spain, and a pan-European Congress chaired by the United States to establish a 'free and democratic Europe based upon principles of self-determination, justice, and peace.' In effect, Roosevelt was demanding unconditional surrender. Should the French refused, 'the United States will not hesitate to deploy these new weapons against targets designated as vital military and manufacturing centers until such time as the terms are accepted.'

Thus, the United States was offering the world a choice: peace on American terms, or destruction by nuclear hellfire. Scientists and leaders from across the Syndicalist alliance began the journey to the Channel coast, curious to see just what this secret new weapon really was.