Chapter 142, Garrowby, 27 August 1941

It had, Halifax had moaned to his wife, been an awful summer. The weather, however delightful for schoolchildren, had proven oppressive for Lady Halifax: the migraines that plagued her had taken hold and it was through gritted teeth and a fixed smile that she struggled to support her husband. And he needed her help; the summer break had been anticipated with a mixture of hope and desperation and had instead become what Lord Halifax had christened a “conspirator’s carnival”. With their coup temporarily scuttled, Eden and his supporters had now thrown their efforts into backing Churchill’s calls for a robust response to the Japanese threat, a clever move apart from one small, though crucial weakness. For it brought Randolph Churchill into their fold.

David Margesson and his Whips had thought nothing of it when a young journalist had sought an interview; such things happened often and were a useful way of informally exchanging views: the newspapers would often come away from the meeting with valuable political information. That this young journalist belonged to

The Times, for so long the fiefdom of Geoffrey Dawson, Halifax’s great friend, was even more reassuring. But, like a thunderstorm in a previously cloudlessly day, the journalist had struck with surprise.

“Darling,” Lady Halifax said to her husband as she crept cautiously into the library and snapping him away from his thoughts, “I can see their car approaching, they’ll be here in a few minutes. Shall I have cook prepare you all some lunch?”

“Thank you, my dear,” Halifax said without looking up. He was retreating increasingly into his history and his faith as a huge swathe of Europe, from the Arctic Circle to the Black Sea, was ablaze. The latest news, partially read on the table next to him, told of the frantic German retreat into Finland. On the main front, Minsk had finally fallen and German armour was racing to the East, threatening the supply lines to the Red Army forces in Leningrad and Finland. In the South, Kiev was slowly, irresistibly becoming a frontline city and a motorised column was thundering towards the Crimea. With an Axis triumph in Russia looking likely, Italy was flexing her muscle and was acting with bellicosity towards Greece: Butler had been despatched to Rome to assure Il Duce that the Empire would not sit back and let him invade Greece, a move that (thankfully) seemed to have German and French support. Eden was confident that with the ongoing wars in the Middle East, Italy could not send much of an invasion force.

“Oh, Dowothy, tell cook to use the left-over gammon. Some sandwiches and potatoes will suffice.”

“I was planning, Edward, to have cook serve beef.”

Halifax looked horrified. “No, no, we’ll have what’s left of the gammon. And I don’t want sandwiches, we shall eat it cold.”

Lady Halifax was about to challenge what she saw as a penny-pinching attitude but realised that further protest was useless. Instead she helped her husband to don his jacket and left him to welcome their guests. She smiled conspiratorially; that Halifax had invited the Chief Whip and editor of

The Times to join them for the weekend was her greatest victory in her summer’s campaign of increasing support for her husband. She had chided him on the need to be courteous, to welcome them as friends as well as colleagues. As she finished her instructions to cook and looked out of the window, she was pleased to see how both Margesson and Dawson were being greeted. Casting an unimpressed glance at the cold meat and boiled potatoes being prepared for lunch she decided to “dress it up” a tad.

“So, My Lord,” Geoffrey Dawson, editor and confidante, one of the most powerful men in the Empire, began. “I am delighted that you chose to invite David and I here, but the question that I must ask is why?”

Halifax sighed. “I am conscious of the importance of consulting with my political allies and friends”. Next to him at the table David Margesson, the Conservative Chief Whip, tensed. Halifax realised that he may have gone too far. “As well as senior Party members,” he added swiftly. Margesson, ever alert, dutiful, inclined his head.

“I guessed, supposed,” Dawson said carefully, “that my lad’s tip-off about Churchill-the-Younger caused it.”

Halifax raised his good hand. “I’d wather we left that for now. I would like to ask you both how the nation and Party view us?”

Margesson spoke first. “Prime Minister, I am facing an increasingly difficult job in ensuring the loyalty of a good third of the Party. Now that the Chancellor has publicly spoken out in favour of Your Lordship’s ministry, you have the support of over two thirds of the Parliamentary Party.”

“Which means that Anthony Eden and his friends are the greatest threat,” Dawson muttered.

Halifax chewed through a piece of cold gammon. “Who, David is the most outspoken of the webels?”

“Winston Churchill,” Margesson replied immediately.

“A ha,” said Halifax, glad that for once something was going according to plan. “And who, Geoffwey, is the most publicly known of our webels?”

“I see your point, Edward,” Dawson said with a smirk, his enthusiasm causing him to call Halifax by his first name. “Winston, of course.”

Halifax abandoned a half-eaten potato and settled back into his chair. He closed his eyes: Dawson was certain that Halifax would have steepled his fingers, if he had had two hands. “So I have to finally challenge Churchill. How do I do it?”

“Well, Randy Randolph; and you obviously concur, as the Chief Whip and I are here,” Dawson said slightly excitedly.

“The Whip’s Office has contemplated removing the Whip,” Margesson said carefully. “But, Prime Minister, such a move was discontinued at Your Lordship’s request. We merely confine our activity to the warnings he received at the election, and the censures over his behaviour in the House.”

“Yes yes,” Halifax said testily, and “I wemain of that opinion. If I publicly slap him down he’ll become a martyr to his supporters. I would pwefer, therefore, to weach an agweement.”

Dawson shook his head. Margesson’s expression was unreadable.

“So, gentlemen, is such a pwoposal possible?”

“My Lord, you know Winston Churchill,” Margesson who had served with both Churchill and Halifax in the Chamberlain Government, stated with feeling. “He will not respond well to an attempt to bully him, nor will he listen to an attempt to do a deal.”

“I agree,” added Dawson. “He’ll just accuse you of trying to stifle his voice.”

“Lord Templewood, Halifax said quietly, “believes that we should use Randolph Churchill’s ongoing difficulty.”

The three men were silent for a while in contemplation of Randolph Churchill’s latest scandal. Dawson broke the quiet. “He’s in a world of trouble: our reporter isn’t the only one to find out about the affair. Half of White’s know about it.”

“I dissappwove of adultewy,” Halifax said sombrely, before adding “if that is what has happened. Is the Colonel pwoceeding with the matter?”

Margesson, who like Halifax wore his establishment credentials more strictly than Dawson, shook his head, not in response to the question but in disapproval of the whole tawdry saga. “He’ll be in hot water with his career if he does,” he said primly. “And anyway, what exactly did Randolph do?”

So Dawson, relying on the notes of his reporter and a few well-placed telephone calls to ‘people in the know’, told the sorry tale. He relayed how Randolph Churchill, trying to emerge from his father’s shadow, had contrived to interrogate his links with the Army. The new tanks, the calibre of their armament, all were subjects of interest as Randolph had built up a wealth of potential questions with which to embarrass Halifax. This was all done with the greatest of fanfare and gossip, and will with a splendid progress of parties and shooting trips. Perpetually broke, Randolph Churchill, abandoning his young wife to the care of his parents, had borrowed a huge sum of money from his financially precarious father; Winston Churchill had therefore funded his son’s infidelity. For at one of the parties, had seduced, bedded and ultimately impregnated the wife of one of his military hosts, Colonel Shannon Mullis of His Majesty’s Irish Guards. His slender, flirtatious wife, Marjorie Mullis, had fallen for the charm of the young MP, so much younger and wittier than her aloof, terse husband. And then she had fallen pregnant. Mullis, who had long ago abandoned any hope of being a father, was immediately suspicious and had extracted a confession; and he was prepared to risk all to avenge his humiliation.

Halifax was intrigued. “How did Wandolph weact?”

“Begged me not to disgrace him. He wants Eden to have a little chat with Colonel Mullis,” Margesson said precisely. “He will be loyal so long as we assist him.”

“So now you need to silence Winston,” Dawson added.

“Yes, I will do it gently...”

“Now, Prime Minister,” Dawson began.

“I will adopt what I believe is the cawwot and stick appwoach.”

Margesson was confused. “Prime Minister?”

“The stick is simple: Winston must be more wespectful to the pwevailing view of the Party if his son is to have a future in it,” Halifax spoke with rare eloquence: he knew that both Dawson and Margesson would carry these words far beyond the gates of Garrowby. “I will extwact the cessation of webellion in exchange for the full wesource of the Party in supporting Wandolph Churchill.”

The plot was hatched. They paused as a servant cleared away the (largely uneaten) gammon, and a tray of delicious looking cakes was brought in. Halifax’s eyes began to widen, more so when Cole entered with a tray of stirrup cups and began to pour from a bottle of sherry with a touch of a flourish. Halifax rolled his eyes; he realised that Lady Halifax had sent Cole into the village to buy the cakes, though he was pleased that Dawson and Margesson seemed to be loving them.

Dawson inspected the impressively ornate stirrup cups. “You mentioned the stick, but I do not see a carrot in all of this.”

“Ah,” Halifax said, enjoying the confusion of his friend. “That is because you have not wead this.” He held up a letter, the proud motif of the President of the United States at its head. “This is a short letter fwom Pwesident Woosevelt, in weply to one sent by me last month.”

Margesson, who as a member of the Cabinet was aware of Halifax’s attempt to engage with the President, looked pleased. “What does it say?”

“A load of twipe, actually. Hot air and whetowic on the need to be careful, not to confuse Tokyo with too many overtures. But he likes our policy on the Burma Woad.”

“Were you considering a diplomatic move from us?” Dawson was intrigued, and like a good editor was already imagining the approach to take.

“May I inject the strongest possible note of caution,” Margesson said quickly. “The mood in the Party would be staunchly hostile to this.”

“Then,” Halifax said tartly, “it is a good jolly good thing that we are not going to do that. The Pwesident, I think, wants to wetain a stwong gwip on dealings with the Japanese. His suggestion, which I like, is that we sit in on the negotiations between Amewica and Japan.”

“Sit in, Edward?” That was Dawson.

“Yes, essentially to show a united fwont. He offers to invite an envoy fwom London to engage in talks. It can, if we wish it, be Lord Woolton, or it can be someone else.”

“Churchill?” Margesson looked horrified.

“No, no, I suspect he’ll want to pick one of his little fwiends to go with Woolton. I am wary of Woosevelt; he stwikes me as a Twickster. I therefore suspect that he’ll fob-off our emissary, but if he is hand-picked by the webels they will have to support him. My letter to Woosevelt, as I explained to Cabinet, was clear in its case that we need to work with Amewica. But I will not sacwifice the Bwitish Empire to keep some tiresome Amewicans happy.”

“How will you put this to Winston?”

“I have invited him to Chequers, where Templewood, Attlee and I, as well as Winston, will pwepare to select the person.” Halifax turned to Dawson. “Your paper, Geoffwey will be essential. I shall make sure that you are given the details of the meeting, with a clear expectation that you will come out in stwong support of a senior, independent, political figure going over there.”

Dawson smiled Margesson nodded his approval. “The backbenchers will like this, Prime Minister. They will probably want a prominent figure to go.”

[Game Effect] – Halifax belatedly deals with Churchill as Lady Halifax continues to be her husband’s best advisor. Is there an element of Lady Macbeth in all of this? Probably not, more that of a loyal wife trying to guide her husband as best she can. With Halifax’s good friend Geoffrey Dawson, the staunchly pro-Chamberlain (and Halifax) editor of

The Times coming to lunch with the Chief Whip, you would assume that a decent meal be prepared. In the finest traditions of the miser, he puts on a characteristically crap lunch which is saved by Lady Halifax.

Dawson, as I have said above, ensured that his newspaper was generally loyal to both Chamberlain IRL, and here Halifax, in not pushing too hard when the dangers of appeasement were obvious. Margesson, though less of a friend that Dawson, was still very loyal and was a superlative Chief Whip, leading the his staff in regulating and enforcing the discipline of the Party. The situation in KFM, with its plots, coups, and internal fighting is clearly a Whip’s nightmare: unlike IRL, where he was moved to the War Office, he has done well to survive the bloodletting and reshuffles and will probably stay where he is.

The real matters in this update, the climax of both the Tory plots and the hesitant attempts to align British and US policy, see Winston Churchill being invited to consider the reply to FDR’s letter. The hardliners are taking over in Tokyo and the Americans will meet with the Japanese. Will Churchill fall for Halifax’s trap? He might, given the chaos in the backbenches and the pressure of the media. Halifax is weak, and so Churchill and his gang may be in a position to wield power. He might nominate a junior MP favourable to the “webels” is sent over to observe the meetings. Would FDR really do this – invite a Brit over there? Well, with a powerful IJN roaming around the Pacific the RN would be useful to the USN. FDR can also use the leverage that working with the Commonwealth (presumably along for the ride) would bring. “Look, Britain, Canada, New Zealand, Australia, all support me” could be a useful argument, one that FDR could grasp if required. But who does Halifax send?

Trekaddict: Percival is a useful “bogeyman” that I can wheel out from time to time.

Kurt_Steiner: Hmmn, genuinely not sure how to take that.

DonnieBaseball: Material does not equate to having a ‘grip’ on a situation, though yes, you are correct that he at least saw the need for reinforcement. Dill himself admitted to Brooke upon the latter’s superseding him as CIGS that he had done “practically nothing” about the Far East.

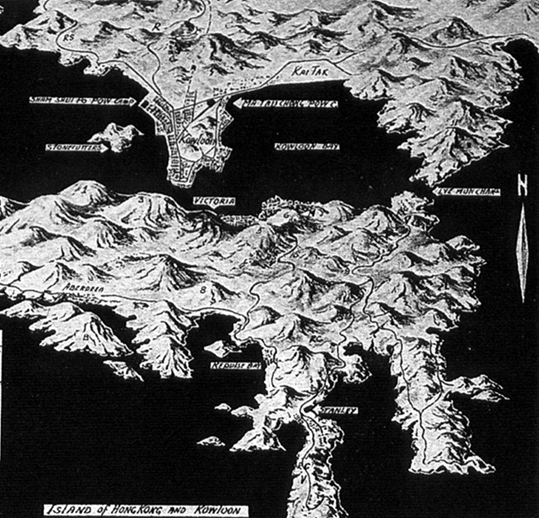

Trekaddict: Funnily enough that thought was ever present in this update – how the defence of Hong Kong (if war breaks out) could be prepared. But the AI is always slightly erratic in attacking Land Forts...

DonnieBaseball: I know, it’s an absolutely great term for a defensive position!

Trekaddict:  MITSGS John:

MITSGS John: Oh, absolutely, the desire to defend Hong Kong is predicated on prestige, pure and simple; can’t be seen to lose out to the natives etc. But it’s a powerful motive for the 1941 British Empire, and one that will command attention for many updates to come.

Trekaddict: Singapore is strategically important, more so than Hong Kong, but don’t rule Hong Kong out. Franklyn has done a decent job in starting to set up a proper Hong Kong Command. Both Singapore and Hong Kong are in a better position than they were in the real WW2.

MITSGS John: Oh dear...

Bafflegab:

Bafflegab: It is a poisoned chalice, but a slightly less poisonous poisoned chalice than the real-life poisoned chalice. I think.

Enewald: I have to confess that the humanitarian aspect of the conflict hadn’t occurred, and Hong Kong probably would be the intended destination of the refugees. Good point Enewald, one very well made.

El Pip: I really think that Lord H would want to cling on to every titbit of Empire he could. Hence Hong Kong will be subjected to a long siege.

DonnieBaseball: Percival as GOC in 1941 refused to heed much of his own advice from ’37. He didn’t really pester Whitehall for adequate resources, dealt lamentably with his subordinates and a disastrously confused relationship with the other services. I agree that a Slim/Monty/Alexander character would also struggle, but when the Imperial troops needed leadership the most all they got was Percival’s indecisive, timid, staff-officer management. He has to shoulder a hell of the lot of the blame for the loss.

MITSGS John: There is also the issue of the fatal underestimation of the Japanese fighting qualities, and one that may cost the Hong Kong Corps dearly.

El Pip: But will Halifax be capable of that?