Chapter three: Preparing for war.

Before the beginning of the war, Britain mobilised herself when the Grand Fleet was assembled by the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill. He combined the First Fleet with elements of the Second and Third Fleets at the Royal Navy’s wartime base at Scapa Flow, in the Orkney islands, thus creating the Grand Fleet, on 2nd August 1914. Its role was to deter any German attack on the British Isles and to be ready for the eventual and inevitable clash with the German fleet in the North Sea. Thus the need to combine various components of the fleets in British home waters into one concentrated force. To command it both Churchill and Prince Louis of Battenberg (the First Sea Lord) agreed upon a name: Admiral Sir John Jellicoe.

Jellicoe had had had a long career in the Royal Navy. He was very professional, calm, ambitious and most importantly, cautious. He had contributed to design the HMS Dreadnought along with Admiral Fisher and seemed earmarked to reach the top echelons of the Navy. A disciple of Fisher, Jellicoe was at the Admiralty, serving as the Second Sea Lord. As Churchill began to mobilise the fleet, he ordered Jellicoe to Scapa Flow where he, eventually, became the Commander-in-Chief of the Grand Fleet. One his first actions was to made the battleship HMS Iron Duke his flagship. While the British public expected a crushing victory over the German navy, a kind of new Trafalgar. However, Jellicoe did not considered that this was reallistically possible. The losses that such a victory may cost would damage so much the Grand Fleet that she would be no longer capable to ensure that the high seas remained British. Churchill described Jellicoe later as 'the only man on either side who could lose the war in an afternoon'.

John Jellicoe, Admiral of the Fleet

The traditional navy strategy in war was a close blockade – something unfeasible in the age of the torpedo and the submarine, which precluded an attack on German bases. However, Britain had an ace in her sleeve: the geography of the North Sea meant that there were only two exits into the high seas beyond: the northern one, between the Orkneys and Norway, and the second one, through the English Channel. The Grand Fleet only had to ensure that the German Fleet would not attempt to exit through either of the two gaps and the German Fleet would be the prisoner and Jellicoe the jailor. Thus, a distant blockade would ensue at the outbreak of war, and the Grand Fleet, which would attack as a giant deterrent, would sail occasionaly into the North Sea in the hope of a clash with the German Fleet, but would not pursue them into German waters in case a trap involving destroyers and submarines had been set up. The Grand Fleet would fight the war by not losing ships, thus preserving Britain’s control of the sea.

With a strenght of 18 battleships, 15 heavy and light cruisers and four destroyer flotillas - after the outdated and eldest battleships had been rellocated to the Channel and the Mediterranean Sea -, the Grand Fleet could be reinforced easily by the four heavy cruiseres of the 2nd Cruiser Squadron (Admiral Gough-Cathorpe), based at Rosyth and the Battlecruise Force, led by the redoutable Read Admiral Beatty and his six fast battlecruisers.

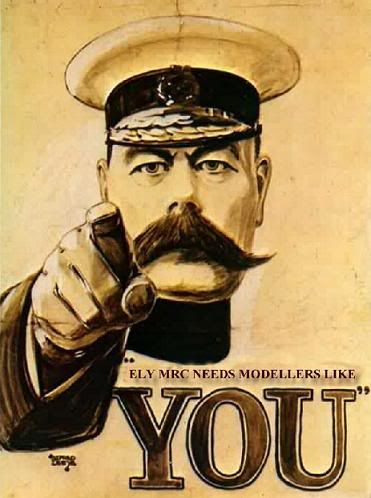

Asquith knew, however, that the Royal Navy was not going to be enough to win the war. As he had taken over the Secretary of State for War since the resignation of J.E.B. Seeley, he saw the was as an opportunity to rally patriotic opinion and to make use of one of the Empire’s heroes. This he appointed Field Marshal Herbert Kitchener, Earl Kitchener of Khartoum, to the War Office. A living symbol of the Victorian empire since his victory at Ondurman, Kitchener was also a formidable organiser with experience in the Sudan, Egypt, South Africa and India, where he had reorganised the Indian Army.

Kitchener managed to leave an appalled government behind when he predicted that the war would last at least three years and that Britain would require an army of three million soldiers with which to defeat Germany. To the politicians, who believed that the war would be short, as no country could bear the financial costs of a long war, those were awful news. Kitchener went on demanding that 100,000 men should be added to the army immediately, along with enough officers be made available for training Britain’s new army, composed of new recruits, who were joining amidst a wave of patriotic fervour at the outbreak of war. However, it would take time for these divisions to come of age. Kitchener's inmediate recruiting campaign for volunteer regular troops created 6 new divisions by the end of August, and was attracting 33,000 men per day in September, the so called Pals Batallions*.

The only land force that Britain could rely on was the British Expeditionary Force It was small and made up of the British Army’s pre-war professional regular soldiers. Thus, while conscripted armies of Europe numbered in the millions, the BEF was just 120,000 strong -Total British Army strenght in August 1914 was 247,342 regular troops (about 120,000 overseas), 224,223 reservists of all classes and 268,777 Territorials-, and an entire corps was to be left in the British Isles in case of a surprise attack by the Germans. However, the BEF was reckoned to be the most professional army in the world – ‘

the best-trained, best-organised and best-equipped British Army that ever went forth to war’, as historians have claimed. The BEF’s hallmark was its quality, not quantity – most of its soldiers had experience in conflict on the North West Frontier Province or South Africa, whereas those in European armies were largely going into battle for the very first time.

The BEF was to be sent, in accordance with the 1911 Committee of Imperial Defence meeting, to France to form on the French Army’s left wing, to ‘dam the German flood’ as it was suspected that a large portion of the German army was going through Belgium, and that the BEF would be required to cooperate with the French Army to halt its advance, before going onto the offensive and helping the French Army to victory. If a German raid against Britain did no took place then III Corps would be despatched to the continent. along with forces from Canada’s regular army while Egypt will provide a staging point for the forces coming from Australia and New Zealand. The German colonies in Africa were to be attacked by the Britain’s existing forces garrisoned across the continent, reinforced by elements of the Indian Army if needed. The bulk of the Indian Army was to be sent to Egypt at first. In the Mediterranean, the Royal Navy would seek to work with the French Navy in maintaining Allied maritime supremacy, and aid their French allies should a decisive clash with the Austro-Hungarian fleet develop. The Navy was also to help in seeing Germany’s Pacific colonies occupied as rapidly as possible.

France had a peacetime army in August 1914 that comprised 47 divisions (777,200 French and 46,000 colonial troops) in 21 regional corps, with attached calvary and field artillery. Separate overseas forces, generally comprising about 60% native troops, were stationed in North Africa, Indochina and Madagascar (110,000 men). By August 1914 further 2.9 million men had been mobilized.

Since 1870 an attacking doctrine (

élan or

offensive à l'outrance) completely dominated tactics developments to 1914, with the stress laid on the psychological effects on oponents of rapid cavalry charges and fearless infantry assaults. This was to mean that machine guns, heavy artillery and tools of trench warfare were neglected, as they were not considered important in the context of offensive field opertions. Field artillery, based on the excellent medium

Soixante-Quince (75 mm) gun, was deployed in small mobile batteries intended for rapid accompaniment of attacking infantry rather than thorough reduction of hostile positions. Doomed with hindshight, faith in spirt over firepower had many important advocates in other Europeans armies, and remained an important influence in French military thinking as late as 1917.

The German Army was recognized as the most efficient land force in the world. It incorporated the ground and air forces of all the German states, although the kingdom of Bavaria maintained an autonomous military administration. The peacetime German Army comprised 50 divisions (700,000 men), with attached cavalry regiments and other support forces. Within a week of mobilization some 3.8 million men were under arms.

The militaristic culture associated with Prussia contributed a caste of senior officers headed by the kaiser as C-in-C. Planning an operational control was conducted by the General Staff (OHL) under the Army chief of staff, who was effective C-in-C of the field armies but dependent on approval from the crown for all major decisions. No army was more efficiently mobilized, effectively manoeuvered or meticulously prepared for every tactical and supply eventuality.

A group of German infantry in full marching order in 1914.

In terms of sheer size, the armies of the Imperial Russia were regarded as a potentially unbeatable force in 1914. The Empire's estimated manpower resource included more than 25 million men of combate age by 1912. However, its main area of vulnerability was its slow mobilization capacity. Modernization was hampered by a determined clique gathered around C-in-C Gran Duke Nikolai, ensuring concentration of resources on isolated fortresses and a bloated cavalry arm.

Despite of the reforms that took place after the defeat of 1905, there was still a shortage of competent officers and a serious lack of NCOs willing to perform long service underr often brutal conditions. The mediocrity of the high command reflected a desperate shortage of young ,vigorous or factionally intained generals. Worse still, the poor roads and railways of the Empire were barely capable of fulfilling peactime requirements of the Army. By August 1914 the army comprised 37 cavalry and 74 infantry divisions. Artillery relied on obsolete, clumsy fortress weapons, but some 1910-pattern light howitzers were produced under license from France. Medium and field artillery were equipped with old Krupp 90 mm guns, but the more modern 76.2 mm model was also used.

*Pals Batallions: Popular term used to describe British Army units composed of volunteers who shared close civilian ties. Batallions of "pals" or "chums" -connected through schools, villages, sports clubs or places of work- enlisted together from all classes of British society, even after the Military Service Act introduced concription in Great Britain in 1916. Pal's Batallions were often encouraged to join in mass by guarantees of postwar employment and economic aid from employers or unions. Out of nearly 1000 battalions raised during the first two years of the war, over two thirds were locally-raised Pals battalions. The policy of drawing recruits from amongst a local population ensured that, when the Pals battalions suffered casualties, individual towns, villages, neighbourhoods, and communities back in Britain were to suffer disproportionate losses