Chapter 12: The voice of the mob

5 February 1860, office of the Minister of Security, Naples

Arturo Orsatti had been Minister for just over a month. One of his first actions was to firmly anchor his headquarters, instead of the "roving HQ" that Magnus von Horgen used. To Arturo, the citizens should welcome the presence of the ministry, not fear it. He'd also been streamlining the ministry. Instead of relying heavily on central control of all ministry actions, Arturo's goal was to install regional Departments of Security under trusted subordinates. That way, each individual region would be able to adjust their policies as they saw fit, without being so concerned about heavy-handed action from the Ministry. Each Department of Security -- he envisioned a total of 10 to begin with, in London, Paris, Madrid, Vienna, Budapest, Constantinople, Jerusalem, Alexandria, Tripoli, and Marrakesh. There would be sub-departments on the major islands as well. While that worked just fine for domestic order and tranquility, investigations that involved more than one department or foreigners were run in Naples; that gave Arturo plenty to do. He also ran the Empire's espionage and counter-espionage, apart from more specific local operations that could be run out of regional headquarters.

his personal life was far less structured, to Orsatti's chagrin. The only reason that Arturo qualified to hold a Senate seat, given the very strict tax requirements, was his own portion of the family's goldsmith in Milan. His father, Vicente, had insisted upon it. Arturo was grateful, as his Captain's salary had been very small indeed, but at the same time, his father often attempted to influence his son in certain ways. Vicente, unlike his son, was a man of firm political convictions -- he was a

Protectores, through and through. Arturo had run as a

Militares, although his own personal ideals remained somewhat muddled. Like many soldiers, he really preferred peace to war, and had briefly considered the

Pecuniares. Thinking of his father, he chuckled softly.

I wonder how much Father earns from my reputation? There was a time when he'd forget my name; now, he'll brag about to me anybody who sits still long enough. Maybe not even then. The thought of his aged father running down a potential client provoked an even louder laugh.

The Senate's most recent decree, however, was no laughing matter.

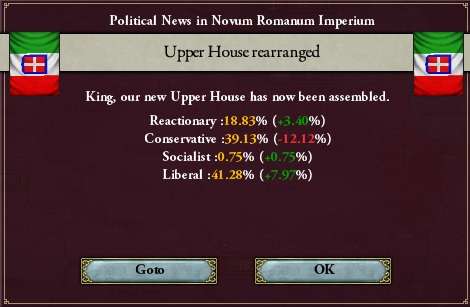

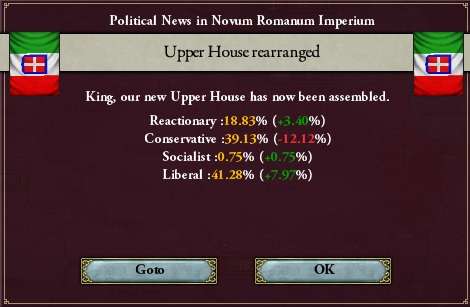

While Karl Marx, the Chancellor, often claimed to be the voice of the people, in this he was actually outmaneuvered by Benjamin Disraeli, the Minister of Commerce. Disraeli, a shrewd politician, recognized that many soldiers and farmers were fundamentally conservative, which made them potential adherents to the

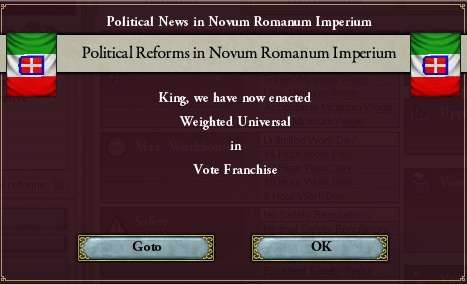

Pecuniares. Marx's own faction continued to evaporate; the Chancellor already recognized that he would not be Chancellor again after the next election. Even Agrippa Germanicus had begun distancing himself from Marx. Only the Minister of Science and Industry, Edward Vickers, continued to support his friend, but only on a personal level. For Arturo, all that mattered was that he'd be responsible for making certain that the elections were fair and that peoples' votes would be properly counted. A farmer got one vote; Arturo's father, on the other hand, got three, like the other capitalists and aristocrats. That had been the compromise with Titus Decimus necessary to get enough Senators to pass the new voting law.

As Arturo continued through his daily mail, part of him ached when he saw the orders for new Guards uniforms. The former Captain had never quite shaken his legionary identity. 38 brigades of Guards infantry -- over 100,000 men -- were being raised to eventually replace the older regular infantry. From a security standpoint, Arturo approved. The Guards were more effective, more deadly, and more loyal than regular infantry. They were also more expensive, and Arturo's budget was directly tied to the budget of the legions. The more the army spent, the more Arturo got, because the law stipulated that he'd receive 10% of the total military budget. (Half went to the legions, and the remaining 40% to the fleets.) As a bureaucrat, he was happy, but as a soldier, that only told him one thing.

The only reason to reform the army dramatically in time of peace was because you didn't expect there to be a time of peace for much longer.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

14 September 1860, the wharves near Palermo, Sicily

The navy lieutenant, like a lot of other officers, spent a lot of time down at the docks. The new Iron Steamers ordered by General Datti were an impressive sight. It was both fun and educational to watch the ships built.

Of course, like a lot of bystanders, he was only about half focused on the ships. The protesters were the other reason he was out there. They were demonstrating against the defeat a law which would have greatly reduced the amount of forced labor used as punishment. Most of the conservatives in the Empire supported forced labor. One Senator from Bordeaux had even said in the

Roman Times that "These people have committed a crime. They should have to repair the communities they helped destroy."

The lieutenant shrugged. It wasn't his concern. More than a few crew mates he'd served with had, in fact, been ex-convicts. They were no worse than any other seaman on the average ship; some were a good bit better. It was all the same to him. Just as he was about to return his attention to the ship, he felt a tug at his shirt sleeve. A kid -- maybe ten years old -- looked up. "Would you like a paper,

Signore?"

"How much?"

"1 denarius."

The lieutenant whistled. Although the British pound was the main unit of currency in the Empire, mostly because British banks had supported so many government ventures, the penny was officially termed the "denarius" after the old Roman currency. It symbolized the curious blending of old and new that was the New Roman Empire. "Times are tough, kid. Have a decimus." The decimus, worth ten denarii, was the other coin often used by Roman citizens. Many a bale of political hay had been made from that particular pun and the leader of the

Protectores. The young man tugged his cap and turned to leave, when the lieutenant got the kid's attention. "Say, what's your name?"

The child smiled faintly. "Nikolai,

Signore."

"Nikolai. I'll remember that. On your way now."

The lieutenant watched the child scamper off into the crowd.

That kid has something. I don't know what, but it's something. I'd better keep an eye on him, see if he comes back. After that, he finally took a look at the paper he'd paid for. "That lousy no good traitor!"

All over Rome, people were coming to the same conclusion, but many had much more colorful words for the Chancellor of the Roman Empire.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

6 May 1861, office of the Chancellor, Rome

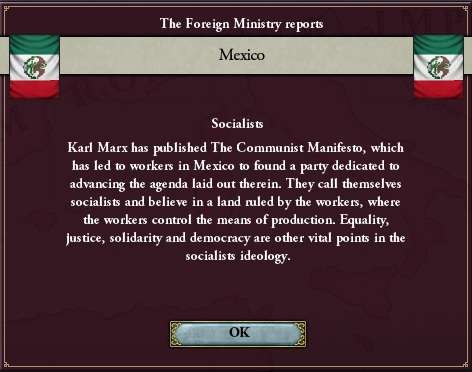

Karl Marx had passed another couple of burning effigies on his way to the office. He'd done his best to ignore them, but eight months of this hell did tend to wear a man down. He'd complained to everybody who had listened that he'd had nothing to do with the so-called "Communist Manifesto" attributed to him; nobody believed him. To make matters worse, the new

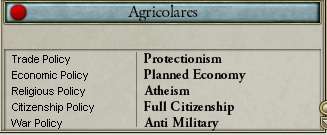

Agricolares faction had tried more than once to name him as their leader. Marx consistently ignored this "honor," but that didn't stop the

Agricolares -- a collective of farmers (which was where the faction got its name) based in Jamaica -- from trying to tap into Marx's popularity.

The new faction became increasingly popular. Ties to Mexico became more and more apparent; the decision of this collective to publish their manifesto in the Mexican capital, Houston, only reinforced these ties. A mysterious "German" had set himself up as the leader of the faction. The identity of this leader was unknown, but even Marx had to admit a lot of the syntax in the Manifesto pointed towards a German author. Marx had no answers, but with or without his blessing, the

Agricolares had already won a Senate seat.

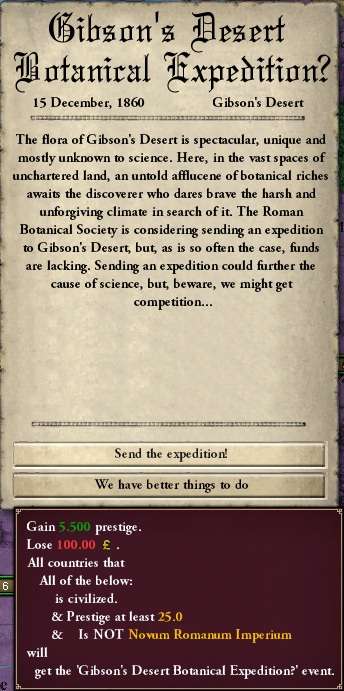

Once again, the socialists (a name some preferred; it emphasized the social good of all mankind, not just farmers, which might draw even more numbers) had offered the seat to Marx, who declined. The Chancellor was already in an uncomfortable position -- as a personal favor to the Empire, a couple of major consortiums in Vienna had named Marx to their board of directors to satisfy the tax requirements to be eligible for a Senate seat. These same consortiums were unwilling to support an obvious liar any longer, and so he was almost certainly going to lose his Senate seat in 1862. His own income was almost entirely based on his office, but he was less concerned about his livelihood than what would almost certainly happen the moment he lost his Senate seat and his parliamentary immunity: prison, if not execution. Marx had done everything he could to clear his name. He'd supported Disraeli's plans for two new canals, Gaius Tullius Cicero's plans to add another 36 brigades of guards, anything he could to buy some goodwill. He'd even gone along with Decimus's patently absurd expedition to the Australian desert to look for some kind of plant.

What idiot looks for plants in a desert? wondered the Chancellor.

He had one last option: to contact the one person who could exonerate him, the most popular politician, maybe even person, in the entire Empire. Arturo Orsatti. The Minister of Security was on his way to the office. Marx knew Orsatti would be tough, but fair. That was all he could hope for. Marx glanced at the clock; the moment the clock in his office struck 3 PM, Orsatti knocked.

You have to admire his punctuality. Audibly, Marx called out for the knocker to come in. It was indeed Orsatti.

"Chancellor, forgive me for my lateness. As you can see, the weather outside is less than pleasant." Arturo was completely drenched from head to toe. Marx shook his head in quiet admiration, then gestured to a comfortable chair across from the desk. "Thank you. How can I help you today?"

Marx stood and began pacing. "I need to clear my name, Arturo. What can I do to convince you that I'm not to blame."

"I don't think you are, Karl. In fact, the Emperor has not even instructed me to begin the investigation." At those words, Marx's attention was riveted to his guest. "I cannot speak for public opinion, of course, and I gather that is what you are most concerned about."

"Well, yes. I have been a loyal Roman since I arrived here; I would never advocate the abolition of private property or any other such nonsense! Where would I sleep? What would I eat? As far as calling for revolution, the Empire has already advanced so much since I got here that any injustices which remain in the Empire will surely be corrected over time." Marx was growing visibly frustrated, but had not yet displayed his famous temper.

Arturo, his expression blank, took out a copy of the offending document. "Let's look at this together, Karl. Have you read it?"

"Every damned word."

"Very good. You will agree that the document, although currently in Spanish, bares the unmistakable mark of a native German speaker?" Marx nodded, crestfallen. "It even looks like some of your other writing that I've had the honor of reading. For God's sake, Karl, it even

sounds like you."

"I cannot deny that."

"So if this is a forgery, you will admit it is an excellent one. Much better than the last time we, ah, had this problem."

"Yes, yes. All of that is true. What of it?"

Arturo withdrew a notebook from his coat. He carefully studied its contents, then returned it to its original place. "Is there anyone you can think of who would have reason to frame you?"

Marx thought furiously. "Magnus von Horgen?"

"I'll admit, he's our best candidate at the moment. He's also read a lot of your work, so he could copy your style. Unfortunately, since he was exiled, I've lost all track of him. More importantly, Magnus tended to be much more direct in his confrontations with you. I have no doubt he'd be screaming it from the rooftops if he were responsible."

Marx frowned. "That does make sense. I have my share of enemies in Wallonia, I admit, but I haven't seen them in years. Do you have the original document?"

"The one sent to the Times? Yes, right here."

Marx stared bleakly at the article, hoping to find some hint of a clue who might have written it. He'd stared at the same word for two minutes before something caught his attention. "This is in Latin. Is that how the document was transmitted?"

"No, actually. In German."

"Do you have that copy? Excellent, thank you." Marx read the German edition much more quickly and fluidly. His Italian had improved, but Latin still escaped him on even his best day. "I recognize the handwriting. Could it be.... Friedrich?" Arturo's eyebrow rose. His huge frame shifted uncomfortably in the chair; the squeaking and cracking didn't distract Marx in the slightest, who took even more care with the document. "Yes, yes, of course. That's why it sounds like me!"

"Who is Friedrich?"

Marx looked up, triumphantly. "Engels. Friedrich Engels. He and I were old friends a long time ago. I was young and angry then; I could not conceive of any land which could address the problems of the world as I saw them. Then I was invited to the Empire. My attitude changed; his, apparently, did not. I had no idea he was in Mexico..."

"You are certain Engels is responsible?"

"Yes, I would swear it."

Arturo had a faraway look in his eyes. "Was he ever a citizen of the Empire?"

"No, he was born in a village not too far from me." Arturo, disappointed, got up to leave. "Wait! Manchester! His parents sent him to Manchester; you should have records of him there!"

Arturo extracted his notebook with a purpose.

"Karl, I need to know everything you do about Friedrich Engels. It may be the only way I can save your life."

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

22 November 1861, Palazzo di Farnese, Rome

Constantine XII had hoped he'd have some domestic peace after the Marx controversy died down. Arturo Orsatti's investigation was expertly leaked to the

Roman Times, and the story vindicated Marx and placed the blame squarely on Engels. The Mexican ambassador consistently insisted they had no idea where Engels was, but that "they would be certain to notify the Emperor if any news became available." Constantine snorted.

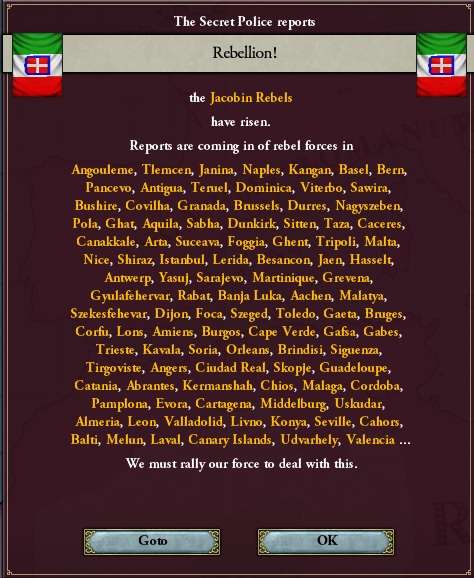

Yeah, like they would lift a finger to help us. Orsatti had a couple of operations going in Mexico, but they had so far not borne fruit. As he glanced at his brother, sitting at the table with the Chief of the General Staff, Cyrus Datti, his brother-in-law, he almost wished for a return to mere political scandal. The Jacobins had risen again.

A quick glance at the map showed that there were heavy concentrations of the Jacobins in Spain, this time. They'd spread all throughout the Empire, but Spain was clearly their base. "Trajan, I thought we were done with the Jacobins?"

The Marshal -- and twin brother of the Emperor -- sighed. "I did, too. We never did catch the mastermind behind the last Jacobin uprising, did we?"

"No, damn it. Arturo swears he'd remember her again if he saw her, but no such luck."

Cyrus rose his finger to gain the attention of both Farneses. "My liege, is it not less important to discuss who is to blame than what shall be done?"

The Emperor nodded grudgingly. Appointing Cyrus as Chief of the General Staff was a purely knee-jerk reaction to the last Jacobin rebellion, but Constantine found himself regretting his decision. Cyrus was never openly insubordinate, but he constantly talked down to the Emperor, as if Constantine were a child and Cyrus his tutor. In military matters, Cyrus was certainly a valued advisor, as he had real combat experience, unlike Trajan or the Emperor. However, Cyrus was always trying to extend his authority, even suggesting to the Emperor that he might, one day, make a capable Chancellor. Cyrus technically had the legal right to run for the Senate, as he could claim citizenship and aristocracy, but the Chancellorship was appointed, not elected. Therefore, even though Cyrus clearly disdained his Emperor, he still had to be polite.

"What is your suggestion, Cyrus?"

"The normal procedure: ordering the legions to eradicate these hateful foes. Investigations only take time, sire, and you surely do not wish your citizens to flee in terror from these monsters?"

Trajan bit his lip. "Brother, while I think Cyrus has a point, doesn't it bother you that the Jacobins keep rebelling? Shouldn't we be more focused on interrogations and arrests?"

Cyrus chuckled politely. "Marshal, you have never been in the heat of combat. Soldiers would almost certainly find creative ways of ignoring your orders: it is kill or be killed."

The Marshal's face clouded with rage. "You forget your place,

General!"

The Emperor rose his hand to stop his brother and brother-in-law from coming to blows. "Trajan, go ahead and give the orders to hunt down the rebels; I'll have Arturo ride out with his own men to try and capture a leader or two. Let's let soldiers soldier."

Both Cyrus and Trajan saluted -- Cyrus's just a touch late -- and left.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

5 August 1862, Office of the Minister of Security, Naples

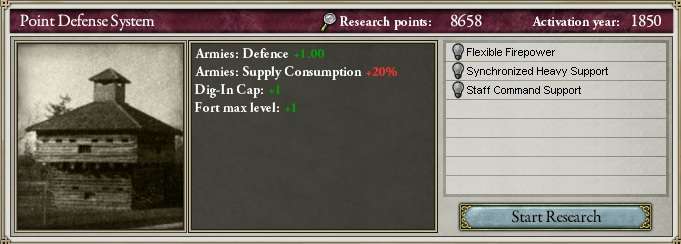

Arturo had spent nearly an entire year tracking down the Jacobin leaders with no success. Only three strongholds remained, all in or around islands near Africa and the Caribbean: Dominica, Guadeloupe, and Cape Verde. Every time Arturo got close to taking down an enemy encampment, he'd find a legion already there and a pile of bodies. Those damnable point defenses, first devised months ago, were erected in mere days, making it nearly impossible for any of the Jacobins to escape.

Orsatti laughed to himself.

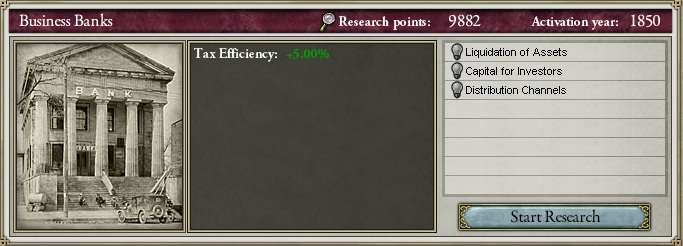

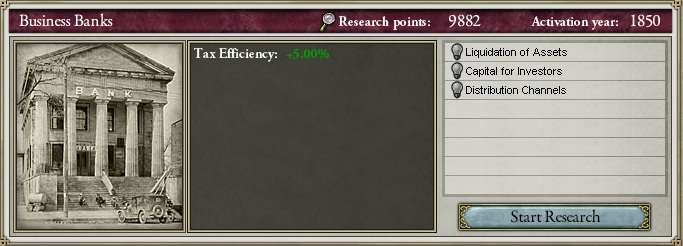

I can't believe I'm angry that the legions are so good. Should I hope they fail miserably? The people of Rome had already shifted their attention to the new tax plan, submitted by the socialist Senator Leonardo Antonelli, the owner of the profitable machine parts factory in Campania. It favored a dramatically lower rate on the poorest Romans. Only 25% of their income could be taken as taxes, theoretically. This was a big difference, as many had paid up to 45% in the past. The middle class would pay only 35%, a 10% decrease, with the richest Romans getting the smallest cut -- they would go from paying 45% to 40%. To make tax collections more efficient, Antonelli also favored the creation of new business banks.

The new plan had already passed; even Disraeli approved, which was, to say the least, unexpected. The rebels were quickly becoming a thing of the past. To bolster the Roman navy, 20 ironclads were ordered, the first in Roman history. The army got bigger too; 23 more brigades of Guards were ordered. Slowly but surely, regular infantry was being phased out of the legions. The only critical part of Rome's defenses that were lagging was Arturo's own ministry. If he were the paranoid sort, he'd be looking for some kind of conspiracy against him. Whether there was or not, Arturo was leaving Italy in another week; he was sailing to Jamaica undercover to attempt to gather intelligence on Engels and to make sure that the

Agricolares were legitimate. The Emperor had ruled that, since they'd followed proper procedures, they could be a part of Roman elections, unless illegal activity was directly tied to one of their members.

Somehow, he didn't think he'd have much time to vacation.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

18 April 1863, Dampier, Australia

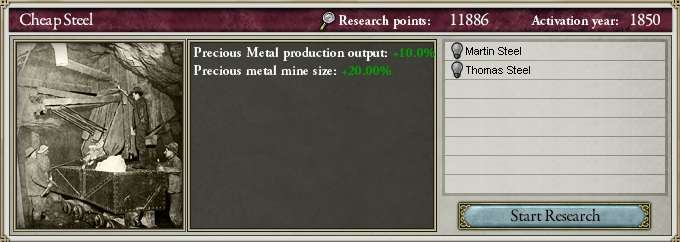

The crew of the commerce raider celebrated the news that, finally, their government was doing something for them. There was an extra cut in the tax rates -- it was now 20%/30%/35% from the poor to the rich -- but that wasn't their cause for joy. Nor was it the promise of new and cheaper steel, which meant more ships for them.

It was something even more exciting; the

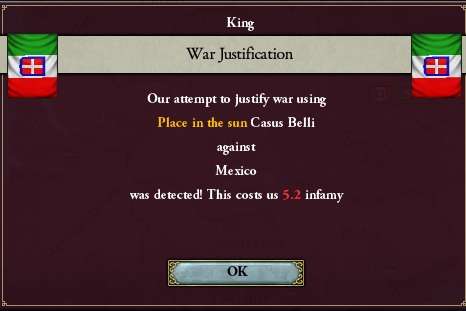

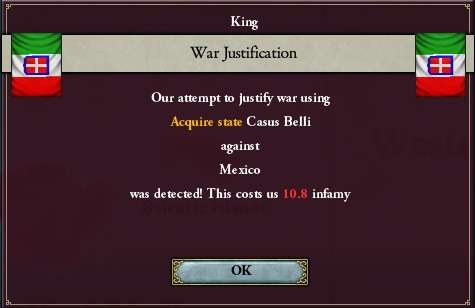

Roman Times broke the story that Roman agents were attempting to plant propaganda stories in the Mexican media, ostensibly to acquire a Mexican colony.

Their army brethren ashore were cheering too; they were gaining even more brigades of guards. The Australian Legion had been waiting for a chance to seize the last bits of Australia for the Roman Empire; the Mexican provinces weren't even being guarded! Surely the Emperor would declare war any day now! Most happy of all were the Australian citizens, particularly those of New South Wales. New South Wales had also been formally accepted into the Empire as the first Australian

provincia.

While his men celebrated, the chief gunnery officer sighed. He'd hoped he could stay in Palermo a while longer; there was a girl there he'd been growing closer and closer to over the weeks. No such luck, unfortunately. Rather than pining away for his lost love, the lieutenant shook his head and made for the hold of the ship. He'd been ordered to do an inventory of the gunpowder barrels by the Captain, and that's exactly what he planned to do. About ten barrels in, one felt a little light. He kicked the barrel, and was rewarded with a loud "Ow!" He popped open the barrel and out rolled a young lad. "What the - Nikolai?!"

The impudent ex-newspaper seller smiled. "Good of you to remember me,

Signore."

"What are you doing here?"

"I wish to see the world, and selling newspapers is boring. You were so kind to me that I knew you wouldn't mind if I came along with you on your adventure!"

"Adventure? This is serious, kid! You could die. We'll be at war with Mexico any day now, and I can't be watching you all the time. Where's your mom and dad?"

Nikolai's impish grin faded away. "I don't have any."

The lieutenant looked a bit nonplussed. "Sure you do, everybody's got some, or you wouldn't be here."

"I'm an orphan,

Signore." Over the next few minutes, the lieutenant got the whole story. Nikolai was born in Sarajevo in 1850. He never knew his parents. He wasn't even sure Nikolai was his real name; he'd only heard people shouting it at him for most of his life. The lad had a had rough life; he'd lived in ten different orphanages. Some were nice, and some were not. As he got older, he'd had to fight, sometimes literally, for every scrap of food he got. Despite slavery being illegal in the Empire, one orphanage hadn't cared and tried to ship him to a country that did have slavery, like the United States. He'd only escaped by pretending to be sick; when his guards took him off the ship to go to the doctor, he'd knocked one out and ran off. He knew five languages from his many orphanages: English, Italian, French, German, and Serbian, his native tongue. Nikolai could puzzle out Latin after a while, but he'd never been formally trained.

The lieutenant carefully appraised the child. He was tough and sinewy -- that part of his story rung true. There were plenty of reminders of the not nice orphanages on his back; he'd even had the beginnings of a brand on his left leg. The kid was fast, even when grabbing something like a piece of salted pork from another barrel in the hold; that was how he'd survived so long. The lieutenant didn't know a Serbian from a Spaniard, but he'd never heard the name Nikolai before either. "What am I going to do with you?"

Nikolai grew fearful. "Please don't throw me overboard and make me swim to shore! One sailor did that a few weeks ago."

The lieutenant sighed. "That would be a long swim. You're in Australia now."

"I am? Wonderful! When do we go ashore?"

The gunnery officer sighed again. "You're missing the point. You're a stowaway. The Captain is liable to clap you in irons until we can get a telegram sent to Palermo, where I found you."

"Can't I stay here? I'm a good worker! I could be a good sailor!"

"You're 13. That's too young to join the fleet."

"But not too young to be clapped in irons?"

The lieutenant was brought up short with that one. As he tried to figure out what he'd do, the Captain himself made his way down the stairs to check on the lieutenant. "Di Marco! Is that inventory done yet? We're going to be running drills later... today... Di Marco, who is that boy?"

Lieutenant di Marco thought as quickly as he could. "He's... uh... my kid brother."

"And why, Lieutenant, is your 'kid brother' on this vessel?"

Before the lieutenant could reply, Nikolai piped up. "Captain, our parents are sick, and he's the only family I've got. Don't separate us, sir, please!"

The Captain, who had three kids of his own, tried, but failed, to keep his heart from breaking. "Poor lad. How old are you?"

"Thir -- er, fourteen, sir." A jab in the ribs by di Marco corrected Nikolai.

The Captain blinked a couple of times, then nodded. "Fourteen. Old enough to be a ship's boy. Look, I'll let you stay on the boat until we go back to Palermo in a few months. You'll follow the lieutenant's orders to the letter. Like it or not, son, you're in the fleet now."

"Yes, sir!" squeaked Nikolai, with a snappy salute.

The Captain held back a smile and returned the salute. As he left the hold to go to the captain, di Marco finally let out the breath he'd been holding for the past minute. "That was a close one. Well, you heard the Captain. Oh, and your name is now Niccolo. Easy to remember?" Nikolai nodded vigorously. "Good. Anybody asks, you're Apprentice Seaman Niccolo di Marco. When we get back to Palermo, you can go where you want. Heck, maybe you should stay in the navy! The Captain can sign your paperwork. Provided you don't screw up. Navy might be the best thing for you."

Nikolai -- no, he had to get used to his new name -- Niccolo nodded.

Me, a sailor? It could work. It could just work.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

9 March 1864, Palermo, Sicily

A year older, a couple of pounds richer, Midshipman Niccolo di Marco proudly walked down the gangplank to shore. He'd done so well on his first cruise that the Captain of the vessel -- an Irishman named Sinclair -- had signed his formal papers without another question about his age. Since then, he'd been on two more cruises -- one to London and another to Jamaica. Now, though, he was going to Naples. Instead of promoting him to Seaman, the Captain was so delighted that he recommended the boy for a slot in the Van Dijk Naval Academy. Despite his lack of formal education, Niccolo was still uncommonly bright, and spent every free minute he could learning what he needed so that he could pass the exam. That he did pass the exam was a source of pride both for Niccolo and his "brother", who was now Lieutenant Commander di Marco. Niccolo checked his list of equivalencies between the army and navy so he could know where his "brother" stood.

1. General - Admiral

2. Colonel - Commodore

3. Commander - Captain

4. Lieutenant Commander - Commander

5. Captain - Lieutenant Commander

6. Centurion - Lieutenant

7. Lieutenant - Ensign

By the laws of the Empire, that meant that Cristoforo was only a rank away from becoming a hereditary noble! Maybe, one day, he could become Marshal! Cristoforo's family had been seafarers for centuries; at least one ancestor had been an Admiral. That gave his "little brother" something to aspire to. Cristoforo's parents had embraced little Niccolo as the second child they'd never had. Nikolai had gotten on to the ship looking for adventure; instead, he'd found a family. As that warm thought coursed through his veins, he got on board the steamer leaving for Naples, only to be stopped by a huge, burly guard. "Sorry, son, no room for you here."

Niccolo drew himself up to his full height -- at a mere 5'4", that wasn't much, although he was always growing -- and showed his orders to the guard. "Pardon me, Midshipman. You still can't get on."

"Why not?"

"Haven't you heard? A new rebellion's breaking out. To make things worse, those idiots in the Foreign Ministry messed up; instead of being able to take Australia now, we have to wait until the formal paperwork goes through again. We got caught even quicker now."

"What has got that to do with me? I need to get to Naples."

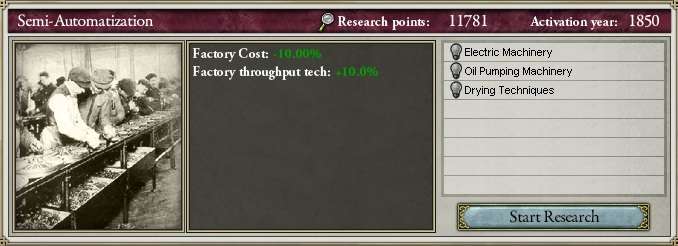

"Look, this ship is for factory workers only. They're testing some newfangled concept to help us get rifles produced more quickly. We're gonna need 'em to handle this newest rebellion."

"Who is it now? The Jacobins again?" Niccolo might only have been a fourteen year old boy, but he'd been reading the newspapers, and it seemed like every other word was "Jacobin" these days.

The guard, impressed with the political acumen of the lad, nodded and smiled. "A good guess, but no. It all started when the Emperor said it was okay for the labor unions to form in Rome."

"Damn Socialists," tried Midshipman di Marco.

The guard bellowed. "Hah hah hah hah! You've got that right! Seems some folks agree with you. They're calling themselves 'White Romans'."

"That's a lot of rebels. Any word on who the leader is," asked Niccolo. He figured he'd want to seem as interested in possible, even though the boy in him just wanted to find another ship.

"Now that you mention it, yeah.

Magnus von Horgen."

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The long awaited update is finished! This one took a long time to write, but I needed to establish some new characters, since we're going to see more naval action in coming chapters. The Mexico thing is all my fault; I wanted the bits of Australia, but didn't know that Mexico had turned it into a state already; I just assumed they'd stayed a colony. I essentially spent 5 infamy for nothing, since I don't want any of the colonies I could have gotten, which were all in the New World. Oh well.