I don’t see your pointGames rules are not a Panacea that some people feel it is.

- 3

I don’t see your pointGames rules are not a Panacea that some people feel it is.

Because the population genetics and immunosensitivies of native Americans were already determined thousands of years prior. There was literally no way they could have prevented being decimated by waves of pandemics. Even literally 21st century -level science and technology could not have fully prevented it.

I would hate if this were an RNG chance that sometimes randomly threw my whole game history out of whack, but I'd be fine with it as a game rule.

15% less lethal Black Death is orders of magnitude less impactful than 100% less Amerindian epidemic mortality, and can also be balanced much more easily.I suspect the black death would sometimes not be so lethal too, simply because of RNG. It happens in CK3.

We could, if we want to assume ahistorical things were happening pre-startdate. That has never been a thing in Paradox's historical line of games (Imperator, CK, EU, Victoria, HOI) before for standard starts.We could easily assume they got the disease a few centuries earlier and have similar immunity to Europe.

I, and those who have disagreed with your post may have misinterpreted your post, but it comes off as you saying there being no evidence of Europeans bringing widespread disease with them which killed large parts of the native population. I don't know about South America specifically, but for Mexico, which I assume you also include since you refer to Cortes, there absolutely is such evidence. In his "True History of the Conquest of New Spain", Bernal Diaz del Castillo mentions smallpox several times, and in two of the cases I would describe it as "large swathes of indian population" dying:There is no hard evidence of epidemics or widespread disease in south america. None of conquistador relations like Cortes or Pizarro letters mention any disease, illness or affliction decimating large swaths of indian population. Could be added as optional start setting if someone fancy to add it to their game.

But to return to Narvaez. He happened to have a servant with him ill with the smallpox, through whom this terrific disease, which, according to the accounts of the inhabitants, was previously unknown in the country, spread itself through New Spain, where it created the greater devastation, from the poor Indians, in their ignorance, solely applying cold water as a remedy, with which they constantly bathed themselves; so that vast numbers were cut off before they had the blessing of being received into the bosom of the Christian church.

About this time another king had been raised to the throne of Mexico, as the former, who beat us out of the town, had died of the smallpox. The new monarch was a nephew, or, at least, a very near relative of Motecusuma, and was called Quauhtemoctzin. He was about twenty-five years of age, and a very well-bred man for an Indian. He was likewise a person of great courage, and soon made himself so greatly feared among his people that they trembled in his presence. His wife was one of Motecusuma's daughters, and passed for a great beauty among her countrywomen.

This expedition was attended by many beneficial results; for the whole country was thereby tranquillized, while it spread a vast idea of Cortes' justice and bravery throughout the whole of New Spain; so that every one feared him, and particularly Quauhtemoctzin, the new king of Mexico. Indeed Cortes' authority rose at once to so great a height, that the inhabitants came from the most distant parts to lay their disputes before him, particularly respecting the election of caziques, right of tenure, and division of property and subjects. About this time thousands of people were carried off by the smallpox, and among them numbers of caziques; and Cortes, as though he had been lord of the whole country, appointed the new caziques, but made a point of nominating those who had the best claim.

On our arrival in Tlascalla, we found that our old friend Maxixcatzin, one of his majesty's most faithful vassals, was no more, he having died of the smallpox. We were all sorely grieved at this loss, and Cortes himself, as he assured us, felt it as much as if he had lost his own father. We put on black cloaks in mourning for him, and paid the last honours to the remains of our departed friend, in conjunction with his sons and relations.

That post was replying to one saying that there could be an alt-history where Amerindians had developed immunoresistance from experiencing the epidemics earlier, so I'm confident they were saying there is no evidence of those epidemics spreading in the Americas prior to European conquest and thus pre-colonial immunoresistance doesn't make sense. However, that is kind of mute since the whole point of an alt history scenario is that alternate things happened in history.I, and those who have disagreed with your post may have misinterpreted your post, but it comes off as you saying there being no evidence of Europeans bringing widespread disease with them which killed large parts of the native population. I don't know about South America specifically, but for Mexico, which I assume you also include since you refer to Cortes, there absolutely is such evidence. In his "True History of the Conquest of New Spain", Bernal Diaz del Castillo mentions smallpox several times, and in two of the cases I would describe it as "large swathes of indian population" dying:

Except in this case, where the game rule literally would be a Panacea for our native American Pops.Games rules are not a Panacea that some people feel it is.

It would be incorrect to call it a genocide. It wasn’t like the Spanish purposefully spread disease in order to annihilate the population as far as I know, it was an incredibly unlucky series of events. Your point that ritual sacrifices contributed to the annihilation of the population is bogus and sounds racist to me. “Moral grandstanding against colonialism” sounds like a cope, it would be akin to moral grandstanding against massacres or pedophilia

Cocoliztli epidemics - Wikipedia

en.wikipedia.org

Generally speaking, famines, droughts, diseases were pretty much always present in south america, while conquest surely excarberated the predicaments of these people. To how extenant these diseases were endemic, and on what part caused by europeans is open for debate, similarly the extent, casualties and impact can be debated. There are a lot of very generous population estimates, arguably gross exaggerations like 25 million value which is absurd, to make it look like spaniards caused terrible genocide, when in reality the matter is not so clear cut. Game could represent this medical and also cultural shock, but it should do it in a fair manner. A civilization that resorted to many sacrifices including children everytime drought or flood happened and large swathes of population died, instead of pulling themselves by bootstraps, surely is partly[if not mostly] to blame for excarberation of their maladies that were tied to the conquest. The point is, epidemics were a part of life back then, but the most important part is that pretty much they afflicted everyone and yet countries waged war, developed and endured them. Aztecs were either not as "amazing" as the modern pop history want to present them, as they lacked any institutional support or prevention against a diseases which repeatedly struck them even before conquistadors set their foot in south america . Its paradox choice how they will present the issue and how much moral grandstanding against colonization will be implemented...

For anyone interested i recommend this lecture by Dr. Jeff Fynn Paul

Loading…

www.universiteitleiden.nl

Here's a transcript

The Myth of New World Genocide - History Reclaimed

Jeff Fynn-Paul is a Lecturer in History at the University of Leiden. His research interests include the economic and social history of Europe and the Mediterranean from 1300 to the present, and urban institutions, state formation, public debt, class and slavery in relation to economic growth.historyreclaimed.co.uk

Furthermore, although the Spanish word viruelas, which appears again and again in the chronicles of the sixteenth century, is almost invariably translated as “smallpox,” it specifically means not the disease but the pimpled, pustuled appearance which is the most obvious symptom of the disease. Thus the generation of the conquistadores may have used viruelas to refer to measles, chicken pox, or typhus.

But let us not paralyze ourselves with doubts. When the sixteenth-century Spaniard pointed and said, “Viruelas,” what he meant and what he saw was usually smallpox.

Where smallpox has been endemic, it has been a steady, dependable killer, taking every year from three to ten percent of those who die. Where it has struck isolated groups, the death rate has been awesome. Analysis of figures for some twenty outbreaks shows that the case mortality among an unvaccinated population is about thirty percent. Presumably, in people who have had no contact whatever with smallpox, the disease will infect nearly every single individual it touches. When in 1707 smallpox first appeared in Iceland, it is said that in two years 18,000 out of the island’s 50,000 inhabitants died of it.

In December 1518 or January 1519 a disease identified as smallpox appeared among the Indians of Santo Domingo, brought, said Las Casas, from Castile. It touched few Spaniards, and none of them died, but it devastated the Indians. The Spaniards reported that it killed one-third to one-half of the Indians. Las Casas, never one to understate the appalling, said that it left no more than one thousand alive “of that immensity of people that was on this island and which we have seen with our own eyes.”

Undoubtedly one must discount these statistics, but they are not too far out of line with mortality rates in other smallpox epidemics, and with C. W. Dixon’s judgment that populations untouched by smallpox for generations tend to resist the disease less successfully than those populations in at least occasional contact with it. Furthermore, Santo Domingo’s epidemic was not an atypically pure epidemic. Smallpox seems to have been accompanied by respiratory ailments (romadizo), possibly measles, and other Indian killers. Starvation probably also took a toll, because of the lack of hands to work the fields. Although no twentieth-century epidemiologist or demographer would find these sixteenth-century statistics completely satisfactory, they probably are crudely accurate.

Probably, several diseases were at work. Shortly after the retreat from Tenochtitlán Bernal Díaz, immune to smallpox like most of the Spaniards, “was very sick with fever and was vomiting blood.” The Aztec sources mention the racking cough of those who had smallpox, which suggests a respiratory complication such as pneumonia or a streptococcal infection, both common among smallpox victims. Great numbers of the Cakchiquel people of Guatemala were felled by a devastating epidemic in 1520 and 1521, having as its most prominent symptom fearsome nosebleeds. Whatever this disease was, it may have been present in central Mexico along with the pox.

We do know that in the first decades of the sixteenth century the same appalling mortality took place among the Indians in Central America as in the Antilles and Mexico. The recorded medical history of the isthmus began in 1514 with the deaths of seven hundred Darién settlers in a month, victims of hunger and an unidentified disease. Oviedo, who was in Panama at the time of greatest mortality, judged that upwards of two million Indians died there between 1514 and 1530, and Antonio de Herrera tells us that forty thousand died of disease in Panama City and Nombre de Dios alone in a twenty-eight-year period during the century. Others wrote of the depopulation of four hundred leagues of land that had “swarmed” with people when the Spanish first arrived.

The Spaniards could never do much to improve the state of public health in the audiencia of Panama. In 1660 those who governed Panama City listed as resident killers and discomforters smallpox, measles, pneumonia, suppurating abscesses, typhus, fevers, diarrhea, catarrh, boils, and hives—and blamed them all on the importation of Peruvian wine!29 Of all the killers operating in early Panama, however, smallpox was undoubtedly the most deadly to the Indians.

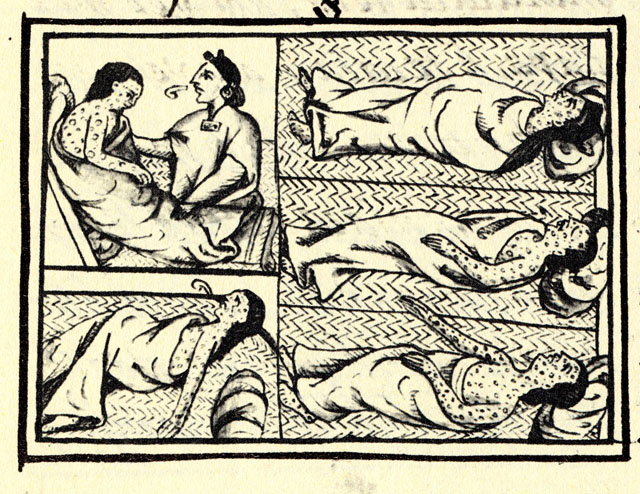

The impact of the smallpox pandemic on the Aztec and Incan Empires is easy for us of the twentieth century to underestimate. We have so long been hypnotized by the derring-do of the conquistador that we have overlooked the importance of his biological allies. Because of the achievements of medical science in our day we find it hard to accept statements from the conquest period that the pandemic killed one-third to one-half of the populations struck by it. Toribio Motolinía claimed that in most provinces of Mexico “more than one half of the population died; in others the proportion was little less.” “They died in heaps,” he said, “like bedbugs.”

The proportion may be exaggerated, but perhaps not as much as we might think. The Mexicans had no natural resistance to the disease at all. Other diseases were probably operating quietly and efficiently behind the screen of smallpox. Add too the factors of food shortage and the lack of even minimal care for the sick. Motolinía wrote: “Many others died of starvation, because as they were all taken sick at once, they could not care for each other, nor was there anyone to give them bread or anything else.” We shall never be certain what the death rate was, but, from all evidence, it must have been immense. Woodrow Borah and Sherburne F. Cook estimate that, for one cause and another, the population of central Mexico dropped from about 25,000,000 on the eve of conquest to 16,800,000 a decade later, and this estimate strengthens confidence in Motolinía’s general veracity.

Generally speaking, famines, droughts, diseases were pretty much always present in south america, while conquest surely excarberated the predicaments of these people. To how extenant these diseases were endemic, and on what part caused by europeans is open for debate, similarly the extent, casualties and impact can be debated. There are a lot of very generous population estimates, arguably gross exaggerations like 25 million value which is absurd, to make it look like spaniards caused terrible genocide, when in reality the matter is not so clear cut. Game could represent this medical and also cultural shock, but it should do it in a fair manner. A civilization that resorted to many sacrifices including children everytime drought or flood happened and large swathes of population died, instead of pulling themselves by bootstraps, surely is partly[if not mostly] to blame for excarberation of their maladies that were tied to the conquest. The point is, epidemics were a part of life back then, but the most important part is that pretty much they afflicted everyone and yet countries waged war, developed and endured them. Aztecs were either not as "amazing" as the modern pop history want to present them, as they lacked any institutional support or prevention against a diseases which repeatedly struck them even before conquistadors set their foot in south america . Its paradox choice how they will present the issue and how much moral grandstanding against colonization will be implemented...

Colonial narratives are still quite pervasive due to much of our written history coming from colonial histories. All revisionists have to do is report on the colonial histories without addressing their function and subsequent bias@CthulhuTactical You do realise that two specific cases of disease missing certain symptoms does not exclude those syptoms from being present in other cases? Have you even read your own sources?

Here are a few quotes from your very own source (https://read.dukeupress.edu/hahr/ar...onquistador-y-Pestilencia-The-First-New-World), touching upon the lack of description of pustules, the occurence of european diseases and the mortality of smallpox:

So your response when presented with one of the (several) sources you claimed does not exist, is that people at the time did not know enough about the diseases to describe them accurately? Your denial of European diseases having a severe effect on the native population seems to very much be based on anything but historical sources or logic. I have no idea what you refer to when you claim modern pop history describes them as "amazing". Most serious historians will blame the swift success of the Spanish in Mexico on a combination of differences in military tactics (such as the Aztecs prefering to take their enemies captive rather than killing them), allying native people who were at war with other natives and diseases. Blaming the excarberation of their maladies on human sacrifice, as you seem to do, sounds like something a 16th century christian would do when trying to explain something they did not understand...

Even the contemporary colonials are quite clear about the matter, at least in the case of Mexico and parts of the Caribbean. This guy seems to argue that the colonials are vastly exaggerating...Colonial narratives are still quite pervasive due to much of our written history coming from colonial histories

Even the contemporary colonials are quite clear about the matter, at least in the case of Mexico and parts of the Caribbean. This guy seems to argue that the colonials are vastly exaggerating...

Johan hinted at disease wiping out population in TT#3. And having a game that covers the period of the Black Death without a disease mechanic would be a missed opportunity. As you said, it's not just the Black Death, there were several echos of the Bubonic plague every generation or so, though to a much more muted degree. And of course the diseases that swept through the New World were likely the largest in world history at ~90% mortality.

No, please. I am incredibly in favor of historical processes over railroaded "flavor", but the train for immunity to Old World diseases had departed a few millennia before the starting date. Best you can do is not have the epidemics coincide with the European invasions, and that will probably give the natives a greater fighting chance, but the seeds for the Columbian Exchange had been planted long, long before the game starts.watching the americas get decimated every time will get very depressing. Maybe have a very low chance that ahistorically they had immuno resistance to western diseases? This would aid the replayability and keep it fun. I think having very low chances of ahistorical things happening, like china spawning industrial revolution (maybe look at the conditions China would have needed to start it, assuming province goods remain constant), would stop every game seeming like an eventuality. The black plague should probably have almost the same effect each time, but later into the game have chances of ahistoricality

Much later edit: I think this should be an optional game rule, this appears to be the bulk of the criticism, along with a stubborn love for history

You don't lose land here though. And while you're losing pops, so is every neighbor around you. Also, you know in advance it'll happen regardless, so I'm guessing the gameplay loop here will be how to best handle the situation. Also, having a serious population decline at gamestart means the 'line-must-go-up' kind of satisfaction can go up a lot more since you're starting from a lower point.It's going to be interesting to see if they can get a system to work that makes you enjoy getting the country destroyed that you just spend hours to build.

We've never really got an internal politics update, because and they never really got antiblobbing mechanics to work because "losing half your country isn't fun". EU IV disasters have a giant "do these things to just skip them!" notification, so that you can avoid them or they bribe you with bonuses when you can't.

I don't think I've ever seen Paradox make a mechanic that doesn't follow the "the line must go up!" principle, without having to change it after the outrage, so I hope this one will be the one

Not necessarily. Milan went full Madagascar in response to news of the Plague: the city was locked down completely, all trade was shut down, and if someone was found to be sick their entire family was walled inside their own home. Methods beyond brutal, for sure: but as the 1360's rolled through, while most of the larger Italian cities had lost up to almost three quarters of their population, Milan still sat at around 120k inhabitants, and it would go on to do absolutely whatever it wanted in Northern Italy for the following half century.You don't lose land here though. And while you're losing pops, so is every neighbor around you. Also, you know in advance it'll happen regardless, so I'm guessing the gameplay loop here will be how to best handle the situation. Also, having a serious population decline at gamestart means the 'line-must-go-up' kind of satisfaction can go up a lot more since you're starting from a lower point.

yeah, I'd agree with the game rule. It would be a fun challenge for a European power to actually have to contend with natives not utterly decimated by diseases, but on the other hand if you want to go historical i think they should allow a railroaded option.watching the americas get decimated every time will get very depressing. Maybe have a very low chance that ahistorically they had immuno resistance to western diseases? This would aid the replayability and keep it fun. I think having very low chances of ahistorical things happening, like china spawning industrial revolution (maybe look at the conditions China would have needed to start it, assuming province goods remain constant), would stop every game seeming like an eventuality. The black plague should probably have almost the same effect each time, but later into the game have chances of ahistoricality

Much later edit: I think this should be an optional game rule, this appears to be the bulk of the criticism, along with a stubborn love for history

Okay sure, but I recon it would be pretty hard to go to war on your neighbors when your entire city/country is walled in. You probably don't want to in the first place if you're risking bringing the disease in.Not necessarily. Milan went full Madagascar in response to news of the Plague: the city was locked down completely, all trade was shut down, and if someone was found to be sick their entire family was walled inside their own home. Methods beyond brutal, for sure: but as the 1360's rolled through, while most of the larger Italian cities had lost up to almost three quarters of their population, Milan still sat at around 120k inhabitants, and it would go on to do absolutely whatever it wanted in Northern Italy for the following half century.