Lords of France: Roads to the Enlightenment

- Thread starter Merrick Chance'

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Just a little french correction

It should be Armée de Bretagne and Armée du Rhin.

French grammar.....

Sorry for not posting here in a long time, but I'm really enjoying the AAR, keep it up Merrick

Just a little french correction

It should be Armée de Bretagne and Armée du Rhin.

Touche, I'll change it between then and now

I am still working my way through this story (I keep on jumping to the end because I have little self control). Anyway, congratulations on the great work.

Early Capitalism under a microscope

It is usually said that France transitioned to a capitalist mode of production with the beginning of the Industrial Revolution and the reign of Louis XIII. Different points are given, such as the invention of the steam-powered factory, the institution of the Banque de Paris, or the Encyclopedic Reforms. But France had been moving towards a financialized economy long before the 18th century, and the French economy wasn't fully 'industrial' (in the stereotypical sense of being dominated by large firms which used mechanical methods) until the 1920s. Thus, instead of seeing the 'Era of Capital' emerging suddenly at any one time, we should see the regime of Bourbon France in a consistent transition towards financialization and industrialization. a transition which was in many ways begun by Henri II's policies.

This financialization and industrialization often was not done by the bourgeoisie; it was instead a development which occurred within the minor nobility. But rather than do my usual thing and discuss the macro level of this trend, I am instead going to put the development of French capitalism under the microscope, and look at the history of one family--the Tocquevilles.

The name de Tocqueville brings to us memories of the 19th century philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville, or that of his father Louis de Tocqueville. But throughout much of the family's history, they were a deeply minor clan which had a mere twelve acres to their name.

Location of the Tocqueville estate within the larger 'triangle of French commerce and industry' which emerged in the 17th century, which emerged mostly due to canal projects funded by the Henri II administration

Located in Normandy since the battle of Hastings, the Tocquevilles were used to ruling in isolation--first from the kings of England, then after the 12th century the Kings of France. Tocqueville-en-Caux was too far away from any major city (Dieppe, Rouen, or Caux) to be of worry to the local governor, or even to the local count. Their 12 acres featured mostly subsistence agriculture (barley and onions being the primary vegetables) with several cattle being raised and enough wine being grown to fill some casks a year. The Tocqueville estate was ruled centrally, with the patrician of the family ruling from the estate's modest castle and the rest of the family supporting the enterprise. Marriage was often a local affair, with the Tocquevilles intermarrying with other members of the local nobility. In this way, the family very rarely interacted with the outside (besides the singular familial merchant, who brought the farm's surplus goods to the market in Dieppe), and the family very rarely grew in size.

The family's first real interaction with the French government occurred during the reign of Louis XI. Through the later reign of Charles VII and Louis XI, the kings had both build a series of forts along the English Channel to defend from a prospective English attack. One of the largest ones was the one at Le Havre, which defended the mouth of the Seine and was finished in 1470. This fort, which became garrisoned with 1,600 soldiers soon after its completion, was one of the first impositions of central power into the area, but it also greatly affected the local economy. Certain estates began growing new crops and owning new animals in order to sell them to the garrison at increased prices. This resulted in the whole region shifting towards export goods, and less intra-regional trade. The Tocquevilles, who did not adapt to this change, were now unable to afford many of their staples and several members of the family (not to mention most of their peasants) starved in the winters of the 1490s

.

Phillipe de Tocqueville, the first member of the family in generations to leave the estate for good

It was in this scenario that the young Phillipe de Tocqueville grew up. The youngest son of four, there was no doubt that he was never going to have any real position on the farm. His early training as an accountant by his uncle was boring and the prospect of being a servant to his cruel older brother for his whole life did not fancy him. What did interest Phillipe was the world which was opened up by him after he became fully literate in French and Low Latin. The Bible in particular interested him. As he read it over and over again, he realized what he wanted to do with his life. In the summer of 1494, Phillipe left to join the Carmelite Monastery de Saint-Marc. And as a talented young individual, Phillipe was able to move beyond the Monastery of Saint Marc as he aged and become the bishop of Caux in 1490. Before Phillipe became a local priest, he was hated by the rest of his family for leaving the family farm. But when the Burgundian Army marched to Normandy in the Franco-Burgundian War, the farm was destroyed and the Tocqueville family found itself depending on the pensions and the tithes given to Phillipe in order to survive. After this, moving out was given far less suspicion, and a good number of Tocquevilles left the farm over the early 16th century.

This was also influenced by the penetration of New World foods into European agriculture. In 1504, the new Baron de Tocqueville Philipe III planted potatoes and squash on the third 'part' of the farm (traditionally French farms in this period were three-plot farms, with two plots being used one year while the third would lay fallow). Upon discovering that potatoes could be grown in fallow land, the agricultural surplus in de Tocqueville's estate (indeed, in most of the farms of Europe) led to a huge population expansion within the area. This, also, led to an expansion within the aristocratic families including the Tocquevilles, and soon members of the family would be all over the region.

Rural industry was France's mainstay until the early 20th century. Spinners like the one depicted produced most of France's textiles for most of her history.

The reign of Louis XII was muddled for the Tocqueville family: on the one hand, the family continued to rise as one of the first potato farmers of the region, and three of the family members joined the army during the Louisan buildup. However, two of the family's brightest young men died in the Armee de Bourbon and the family was split during the French War of Religion. Most importantly for the family, though, was the death of the patrician, Jean, which occurred just as the laws of Normandie were being brought in line with France's larger set of civic laws. These new laws held that if a family member dies without a will, that the family member's possessions were to be split equally among his inheritors. This, effectively, split the Tocqueville estate into five different parts, and further encouraged the younger members of the family to leave the estate.

The young Martin de Tocqueville was one of the most famous of these move-outs in the early 17th century: he is remembered as one of the many young men convicted by Vigny during the Artois Affair and sent into horrid exile deep within the provinces. But, to the family de Tocqueville, Martin's history begins with his exile from politics--he came back to his land, the most fallow in the estate, and saw an opportunity. Martin turned the area into a sheep farm, and involved his peasants in the 'processing' of the sheep's wool into textiles. He then sold these textiles on the Dieppe market. Within five years, Martin had grown to be a very rich man.

The Tocqueville estate, 1620-1670

This process (which had been used in rural France for centuries), was turned into an art form by Martin. Plowing his ever expanding profits back into his farm, Martin involved more and more of his family members. Furthermore, he used portions of the money he gained in the textile industry to make loans in the region to other aristocrats who were attempting to rise beyond the sustenance farming of their ancestors. Many of the men Martin loaned money to defaulted on their loans, and Martin (who's son had grown into a highly capable lawyer) was able to take much of their land in settlements. By 1637, the estate of Martin de Tocqueville had reached the Atlantic Ocean, and Martin was getting ready to start the building of a small port from which he could export his textiles to Bruges or Caen.

This shifts us to the son of Martin, Michel de Tocqueville. For while Martin's astonishing business acumen was rapidly making him the richest man in Normandy, it was Michel who catapulted the Tocqueville family into the realm of the Great Houses. Michel, the lawyer of the Tocqueville family and the family's advocate at the regional capital of Rouen, had often been enraged by the deeply differing levels of infrastructure in Upper Normandy (aka the area east of Caen, where the Tocqueville estate was), Paris, and the French Lowlands. When Michel's younger brother Louis (this generation's seller, who was far more well traveled than his ancestors ever since the development of the family's wool industry) was in Bruges, or Paris, or Amiens, Michel found it easy to send him letters. But Michel had to accept months with little to no connection to his younger brother (one of the family's most important member) when Louis was in Calais, or western Normandy, or even Beauvais--which was a mere 50 kilometers from Rouen! Something had to be done, Michel thought. In 1645 he had an idea, and chartered a carriage directly to Paris.

The Tocqueville Postal Company served much of the French Lowlands, Normandy, and Paris through the 17th century, and later on was involved in sending mail to England, the Netherlands, and the French colonies

Henri's reign was one of massive concentrated infrastructure projects in the area around Paris. The massive amount of money he had spent on canal projects along the Seine and Escaut rivers had connected the economies of Bruges, Paris, and Caen into one massive economic area, but these projects hadn't been cheap. While Henri wanted to continue to expand France's infrastructure, he wanted to find a way of doing it cheaply. Michel de Tocqueville's offer, of opening a jointly owned postal company which would start in Paris and grow to serve the centers of the French Lowlands (which included Normandy east of the Seine as well as Paris), was music to Henri's ears, and after some work with the French bureaucracy, Michel was able to charter the company.

In-game events. Under Henri I set up post offices throughout the French Lowlands

The postal company was able to go through a similar rapid expansion that Martin de Tocqueville's wool operation had, and the Tocqueville Postal Company was soon able to send financial news, personal letters, and governmental information all across northern France by the death of Michel, and the family soon transitioned from caring mostly about textiles to the maintenance of the company.

Growth of the Tocqueville Postal Company, 1640-1750

What do we see in the familial history of the Tocquevilles? Capitalism was not brought about, merely, by new inventions but also had a cultural aspect to it. "Rural industry" in the method of Martin, had existed for centuries and would continue to play a large role in France. Furthermore, Martin would not have had to start such a successful business had the option been open to merely sell wine or cheese; industrial operations began in Northern France out of desperation rather than any objective knowledge of profit. Furthermore, we should note how much of the Tocqueville's expansion came from finance. But this wasn't the finance of the modern day, used to gain more profits. Rather, Martin deliberately gave loans to people he knew could not afford it in order to 'repossess' their lands, that is, finance was used in the 17th century towards feudalistic ends (and this process led to the concentration of land in many other areas of France).

Lastly, we should see how the development of markets in Ancien Regime France was deeply interlinked with the government and with the aristocracy. While this interlinkage is seen by some as a reason to put the development of French capitalism later (say, the 1750s, or the 19th century), such a statement relies on an idea of markets which would be anachronistic to our own time as well as the past. In the modern day, government monopolies (on electricity, water, etc) exist alongside a system of private firms. In France, such a system existed also in the 1640s, but it was a system which was often used to aristocratic ends--oftentimes the motive to profit was sublimated under a wider aristocratic desire to have social prestige, and thus many French merchants and French mercantile-aristocrats ended up losing their money to the extravagant lifestyles required of the nobility in the 18th century. The Tocquevilles lost much of their money in the 18th century for precisely this reason, and Ramon de Tocqueville ended up selling his family's share to the government in 1734. Thus, while the Tocquevilles are a minorly important family in the context of French politics, they are hugely important in the history of Normandy, and are a great example of the complexities of early capitalism in France.

Sorry for the unexpected entry, I've just been moved by MondatoPotato's AAR into thinking about the question: how do I characterize and flesh out the world of France during the period of this AAR? While I do like the direction I've gone in Lords of France, it's obvious that my history is mostly limited to the world of French courtly politics, foreign relations, and the army. Most every day people don't experience history this way--we live within 'great events' like recessions or depressions or booms, but our fates are determined more by local events and things that may seem 'insignificant' when one takes a larger perspective. For instance, for many people the biggest event of the 1990s and 2000s isn't the war on terrorism, it is the expansion of the restaurant industry. So with the Tocquevilles I wanted to explore a family that only tangentially related with the state before the reign of Henri. And don't worry, we'll return to our usually scheduled programming with the next section (which is nearly done), but I will occasionally have intermissions which discuss familial histories of people who may come up later in the game, or may not. I chose the Tocquevilles mostly due to the game engine's love of giving advisers the name 'de Tocqueville'

Last edited:

Really enjoyed that last update Merrick, fantastic writing and particularly enjoyed and industrial and commercial story being told from a personal point of view. Very skilful linkage to in game events. I will be looking forward to more updates in this vein as your narrative permits

The growth of the Quebec Royal Company

With the newfound shortfall France had with the loss of her Rhenish territories, the Henri II administration was forced to look somewhere else for funds. This is not to say that Henri wasn't already looking to the colonies; even as a child Henri was being raised to stories of the Chinois and the Quebecois. But the Rhenish Affair allowed Henri to gain some focus over what his administration would be, and besides his funding for the arts, his greatest and best known achievements are his expansion in the New World, the creation of the Navigation Acts, and eventually the chartering of the Compaignie Française-Indienne and the Compagnie Française-Chinoise. But his work on expanding the French colonial sphere began with his reorganization of the Quebec colony.

Quebec had been running on cruise control since the early 17th century. The early appointment of the charismatic Inquisitor Richelieu as head of the Quebec Inquisition began Vinge's long tradition of disinterest in colonial affairs, and after that appointment Richelieu slowly destabilized rivals, created a powerbase for himself (including his own private army and navy), and by 1630, Richelieu was the 'absolute monarch' of Quebec, just as Henri was the absolute monarch of France. Richelieu's patronage networks, the Quebecois inquisition, as well as his control over a local military (30 militarized transport ships, three line infantry brigades, and a light infantry brigade) allowed the Cardinal to build his own society, similar to the way that Henri attempted to build a gentilhomme society with his policies.

This can be seen in Sacremont's rapid settlement. In 1603, when Richelieu was appointed, the town had consisted of only 3,000 souls and consisted mostly of monasteries and the military garrison. Over the next two decades, Richelieu settled families, especially artisan and merchant families, on the island, until in 1630 the city of Sacremont was a city of 16,000. There was every indication that Sacremont would develop into a North American Paris, with an economy based around its government and its large numbers of monasteries and schools. Indeed, when Richlieu opened the L'ecole de Quebec in 1626, he was moving to do just that: to make Sacremont into the governmental center of the French New World.

L'Ecole de Quebec is one of the oldest institutions of primary education in the New World, and was set up by Richelieu to prepare young men for the Church and the law.

His laws against selling liquor to Native Americans enraged the frontiersman groups, who had used liquor as their key trading good for a century. It also enraged the integrated Catholic-Native American population, who were also included in this reform. But last of all, it infuriated the French military leaders in Quebec, who were used to bringing casks of wine with them during deep patrols of the Quebecois frontier in order to trade for food.

This conflict with the military was one of many—with many of the largest dissident monasteries being dissolved, the military was Richelieu’s largest rival. They had a closer link to the French government due to their constant reappointment, threatened his monopoly of force on the region, and were more popular with the people since they tended to use their force to protect frontiersman from threatening Amerindian tribes rather than attacking 'threatening' monastic orders. Lastly, the military forces in Canada had been commanded for the last 5 years by the hero of the War of Hispaniola, Andrew van Rosen.

Van Rosen commanding an expedition into hostile Iriquoi lands. The Iriquoi confederacy had split multiple times in response to English, Dutch, and French incursions. Van Rosen's diplomatic acumen (and his experience of forming treaties with local tribes) allowed him to end several border crises on disputed lands through the 1630s and 1640s.

Van Rosen, as the Commander in Cheif of the military governorships along the southern border, was enacting a different settlement policy. He saw the New World as a place which could possibly be free of the conflicts of the Old World, conflicts which had given him horrible trauma and an enduring alcoholism. His method of creating a more peaceful society led to him supporting the settling of smaller communities--in Acadia, outside of New Aberdeen no town was allowed to be larger in size than 200--and to a relentless support of trade and commerce, including trade with the English and the Dutch.

The larger context of North America, and the context of the Quebec colony--white stripe indicate provinces led by Richelieu's allies, black lines indicate military governorship, and grey indicate 'claimed' lands which were generally ruled by Amerindian tribes

This conflict continued, without escalating, until the early 1630s. This spoke as much to Van Rosen's willingness to coexist with a man he considered deeply dangerous as it spoke to the caution Richelieu held in situations where he saw no win in a contest. It was with the economic growth of the Quebec Royal Company that the conflict between these two colossal figures came to a head.

It was a conflict which was as much over the distribution of the Company's enormous profits as it was a conflict over the new ideas which were uncontrollably entering Quebec. The realization by Quebecois townspeople both that they could reap enormous rewards from their control of Quebec's fur trade and that Quebec was decades behind France culturally shook the whole of the colony.

The arrival of the QRC's merchants to the many small towns of Quebec was a shock to the colony, both economically (where it led to massive growth from a deeper connection to France) and culturally (as colonists discovered the philosophical developments which had been occurring in France)

Van Rosen had long been resettling 'rationalist' monastic orders into military lands, which was directly against Richelieu's laws against harboring enemies of the state. Richelieu had seen no need to convict Van Rosen so long as the balance of power was in Richelieu's favor. But as Van Rosen became more and more powerful, his flagrant abuses of Quebecois religious law became all the more enraging to Richelieu. It was in the spring of 1633 that the other shoe dropped--during that year Van Rosen had settled a group of 600 Dutch and Scot protestants into New Aberdeen as a part of a trade deal he had made with the governors of New Zeeland and the English Colonies.

Nouvelle Ecosse, or New Scotland, had been populated by Scottish Catholics during the 1610s, but Van Rosen's policies of settling groups in small villages meant that the increasing flow of colonists to the fertile and resource-rich peninsula had led to the population of most of the island's coast

The trip to France was five months long long and dangerous--multiple storms nearly sank Van Rosen's transport, and (ironically) the ship was forced to dock in the Republic of Iceland to trade for food. When Van Rosen reached Caen, he was told that he would be tried, personally, by the King and the First Minister St.Chamand.

Van Rosen was brought to the Louvre, expecting at best, a lengthy stay at the Bastille, and at worst, to be drawn and quartered. Instead, he found St.Chamand "with a vague smile" and had his hand personally shaken by the Marechal du Nord, Xavier le Tellier. When asking what the verdict on his crimes was, St.Chamand replied "Heresy is one thing, Smuggling is quite another", and told Van Rosen that in the time it took him to cross the Atlantic, a message had come to the Louvre telling of Bishop Richelieu's death. Henri was planning on a reorganization of Quebec along more trade oriented lines, and the death of Richelieu was just the time to do it. At the same time, the Navigation Acts had led to mass smuggling, something which Van Rosen, with his experience in border control was just the man for.

And thus, Van Rosen was put in charge of the Quebec colony, and was able to enact his 'new villages' policy throughout the Canadian wilderness. This led to a strong tradition of self-governance in Quebec. Van Rosen's appointment as governor of Quebec marked another move into the growth of the military's power in the French colonies. No longer merely protectors, the officer class now had a say in the politics of their garissoned states, and Van Rosen's revolutionary changes of Quebecois society shows that this say could mean a lot. Van Rosen did not solely try to create a society of small villages, though. Instead, he combined his own view with that of Richelieu's--Sacremont was going to remain the New Paris of New France for time eternal, but it would be a mercantile capitol as well as a governmental one. Furthermore the majority of settlement would now occur in small doses along the Canadian wilderness. Sacremont's position as the center of trade for the new world led to immense riches going directly to the French state, and his leadership meant that Henri's view of society would now on both sides of the Atlantic.

Andrew Van Rosen, second governor of the Quebec Royal Company, and the center of trade in Sacremont (it would soon rise to a 700 ducat center after the collapse of British trade)

Great update as always. Will France's future colonies also be develop along van Rosen's lines?

Also something that cought my eye was: "The untied Mexican States". What is that? An Empire of central american Natives?

Also something that cought my eye was: "The untied Mexican States". What is that? An Empire of central american Natives?

Great update as always. Will France's future colonies also be develop along van Rosen's lines?

Also something that cought my eye was: "The untied Mexican States". What is that? An Empire of central american Natives?

Oh, that? Yeah that's me not editting the image properly. It would be a cool concept but as far as I've gotten in the game (1767) there have been no Latin American revolters yet

A nice chunk of Colonial Empire there. Given the relative failures of your opponents to consolidate any kind of power, I wonder if it'll survive to play a part in the revolution.

A nice chunk of Colonial Empire there. Given the relative failures of your opponents to consolidate any kind of power, I wonder if it'll survive to play a part in the revolution.

My only answer to that is, yes.

My next section, on the French East India Company, might take a while because I have two finals to write. On the plus side, when I was confronted by my Counterinsurgency midterm (and the beginnings of my final report for it), it was really intimidating until I told myself "well, just write it like an AAR". The midterm got an A+ and I'm going to expand on some of my theories in my final report. woo

Last edited:

Apologies about slowness, but to reward you for your patience I present you a bit of a spoiler of a couple entries ahead:

Title: China in 1649 overlaid upon modern political borders

Title: China in 1649 overlaid upon modern political borders

Good update about New France. Could I have an estimation of the population of the north american colonies?

Well most of the population is based around the saint omer river valley. The Canada province got three separate events that gave it +10% population growth each during the 1610s and got yet another religious immigrants event in the 1620s. That left the province with a population of like 20k. The other provinces aren't anywhere near that though Acadia is closing on 8k. The British and Dutch colonies don't even come close population wise though I think that the Spanish colonies are pretty large due to their Amerindian population.

Last edited:

Quebec is building a rich, interesting character all its own, fascinating stuff.

On the map, is all that blue Sweden?! I think that colonial monster needs taking down a peg or two and with relatively small Sweden stretched across both India and China, even if fellow Europeans don't intervene I think there's a chance the local governments might put the boot in when the opportunity arises. I guess that's Dutch Taiwan too, what are the purple and grey-ish entities?

On the map, is all that blue Sweden?! I think that colonial monster needs taking down a peg or two and with relatively small Sweden stretched across both India and China, even if fellow Europeans don't intervene I think there's a chance the local governments might put the boot in when the opportunity arises. I guess that's Dutch Taiwan too, what are the purple and grey-ish entities?

It'll come up in two entries, but Scandinavia's increasing influence in southern China and the increasing financialization of the Chinese economy both sapped the Ming Dynasty of its legitimacy. Large numbers of Neo-Confucian traditionalists thought that China was moving towards an age of decadence and that the collapse of the Ming Dyansty was immanent. The ascendance of the Chongzhen Emperor, who was influenced by this Neo-Confucianist revival, led to a crackdown on the merchant class and on the Swedish administrators. Furthermore it led to strained relations with Chinese Buddhists who had by and large supported foreign trade. A war by the Chongzhen Emperor against Tibet in 1632 was committed in order to solidify the Emperor's control over Chinese Buddhists. However, this opened Ming up to an invasion by the united Manchu hordes. The Manchus take Beijing and in 1636 declare a new dynasty, the Qing Dynasty.

This declaration led to a splintering of China. Too many changes had occurred for the Southern Chinese to accept the continuation of the Dynastic Cycle. The Dali Kingdom, based on ultraorthodox Confucian beliefs, breaks off from Ming in 1642, and Sweden's influence on Guanzhou, Guangxi, Jiangxi, Hainan, and Hunan provinces increased. Most worried of all were the people living in the Fujian and Zhejiang provinces, the centers of Ming trade. Deeply influenced by commerce with Europeans, the traders of Fujian and Zhejiang also sought a break from the past, but in this case they sought a break via their idea of Western values. The Min Kingdom was formed by a group of Chinese and European bureaucrats and led by the philosopher Hung Ying-Ming who took the name the Lien King (the Lotus King) in 1645. In 1649, the Qing have kicked the Ming out of most of Han China and are readying themselves to move south of the Pearl River. The Scandinavians, who only have 15,000 troops stationed in China, call for help.

This declaration led to a splintering of China. Too many changes had occurred for the Southern Chinese to accept the continuation of the Dynastic Cycle. The Dali Kingdom, based on ultraorthodox Confucian beliefs, breaks off from Ming in 1642, and Sweden's influence on Guanzhou, Guangxi, Jiangxi, Hainan, and Hunan provinces increased. Most worried of all were the people living in the Fujian and Zhejiang provinces, the centers of Ming trade. Deeply influenced by commerce with Europeans, the traders of Fujian and Zhejiang also sought a break from the past, but in this case they sought a break via their idea of Western values. The Min Kingdom was formed by a group of Chinese and European bureaucrats and led by the philosopher Hung Ying-Ming who took the name the Lien King (the Lotus King) in 1645. In 1649, the Qing have kicked the Ming out of most of Han China and are readying themselves to move south of the Pearl River. The Scandinavians, who only have 15,000 troops stationed in China, call for help.

I am *so* sorry that it's been so long since an entry came out. The last two weeks of July involved me doing every step of two research projects and my brain has been mush since. Also sorry if this entry is a bit clunky, my brain is still pretty mushified

The Royal East India Company and China in the early 17th century

The Royal East India Company started as a slaving firm and grew to become one of the richest colonial companies of the 17th century. Its swift rise to the strongest colonial power of the 17th century occurred over the first half of Henri’s reign, due the inordinate amount of attention to Bourbons gave to the Far East (starting with Henri, who had been raised on stories of the riches of China), and the fantastic position that the Royal East India Company had at the beginning of the reign of Henri II.

The Royal East India Company started as the French Angola Company, which administered a small number of outposts of the South African coast. The Company was led by Francois le Tellier, one of the richest of Vigny’s supporters during the early Regency, and it did not seem to most outsiders that the FAC would amount to anything. Le Tellier knew otherwise—he knew that the sudden drop in the demand for mercenaries and pirates (caused by legal provisions in the Treaty of Mayence as well as the long peace after the 40 Years War) meant that he could recruit thousands of men on the cheap, and that this would give him a key advantage against his far less militarized English, Swedish, and Italian competitors. Although Le Tellier was complacent at first with merely raiding trading routes from his ports in Angola and expanding the Angola colony into the largest European settlement in Africa via the use of military force, he would soon look for sources of income within the Indian Ocean itself.

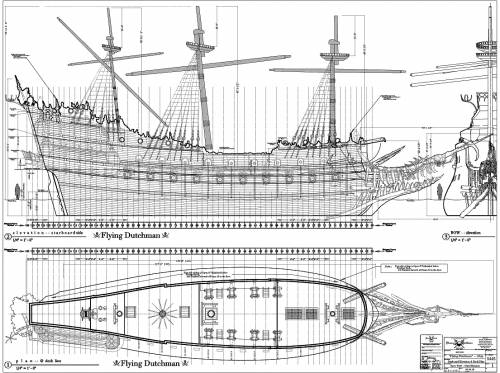

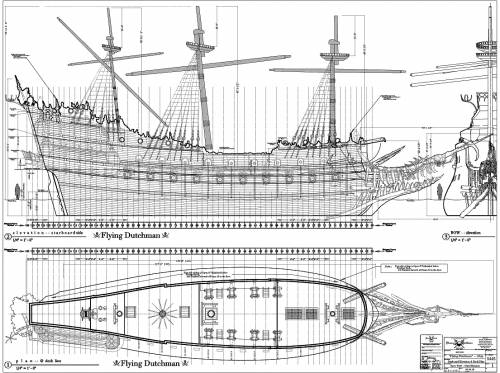

The Flying Frenchman was one of the many ships commissioned by the French Angola Company, and over its 50 year lifespan it went from one of the most infamous pirate ships of the Caribbean to one of the Kingdom of France’s most respected anti-piracy ships of the Straights of Malacca

Henri’s ascendency to the throne coincided with the French Angola Company’s first acquisition in the Indian Ocean--two ports on the island of Madagasgcar. While trading had occurred between Madagascans and Europeans for decades, the constant conflicts between the coastal kingdoms and the warlords of the mountains had made any European settlement impossible. The French Angola Company solved this by sending 7,000 soldiers to the island to bring ‘peace’ to the island and to build wooden forts around two harbors. This news was greeted with great applause within the Louvre, and Henri responded to it by renaming the company the Royal East Indies Company, creating a law giving the company a subsidy of 5 million livres a year, and giving the new company the responsibility of finding trade in the Indian Ocean and in the Far East.

In order to fill this responsibility the REIC took on the same colonization strategy the Quebec Royal Company had--they took ‘central points’ under their direct control, using them as chokepoints for native traders. These strategic points had to be easily defensible while being central to the flow of trade.

The conquest of the Maldives, Ceylon, and Aceh

The Island Wars--during which the REIC conquered the Maldives island chain, the kingdoms of Ceylon, the Aceh sultanate and the tribes of the Andaman islands--occurred over the 1620s and led to a huge increase in the assets of the Royal East India Company. Administered by Captain Guillem de Saint Omer (the great grandson of the famous explorer) and the colonels of the War of Hispania, the wars featured an evolution of the strategies used by Van Rosen against the Portuguese. First, the REIC navy would destroy enemy fleets and enforce a blockade. Second, troops would land and would remain on the coastal areas while supported by the fleet, defeating the enemy’s standing army. Lastly, interior areas would be taken with the help of native allies, would would then be used as the nominal government of the new dependency.

This put the REIC in the perfect position to dominate the trade of the Indian Ocean, and soon the REIC was trading along the South China Sea. By 1629 the REIC dominated the silk trade and was providing naval support along the whole of the Chinese coast. Indeed, on the Fujian and Zhejiang coasts it was more common to see a representative of the REIC than a representative of the Ming Dynasty. This put the French in a precarious position when the ‘great crisis of the 17th century’ occurred. The collapse of the Ming Dynasty triggered the world’s first international intervention and, to the Chinese, began the Four Kingdoms period, a time of great upheaval and great innovation. In the next section I will discuss the history of China in the late 16th and early 17th and the beginning of the Four Kingdoms period.

The Royal East India Company and China in the early 17th century

The Royal East India Company started as a slaving firm and grew to become one of the richest colonial companies of the 17th century. Its swift rise to the strongest colonial power of the 17th century occurred over the first half of Henri’s reign, due the inordinate amount of attention to Bourbons gave to the Far East (starting with Henri, who had been raised on stories of the riches of China), and the fantastic position that the Royal East India Company had at the beginning of the reign of Henri II.

The Royal East India Company started as the French Angola Company, which administered a small number of outposts of the South African coast. The Company was led by Francois le Tellier, one of the richest of Vigny’s supporters during the early Regency, and it did not seem to most outsiders that the FAC would amount to anything. Le Tellier knew otherwise—he knew that the sudden drop in the demand for mercenaries and pirates (caused by legal provisions in the Treaty of Mayence as well as the long peace after the 40 Years War) meant that he could recruit thousands of men on the cheap, and that this would give him a key advantage against his far less militarized English, Swedish, and Italian competitors. Although Le Tellier was complacent at first with merely raiding trading routes from his ports in Angola and expanding the Angola colony into the largest European settlement in Africa via the use of military force, he would soon look for sources of income within the Indian Ocean itself.

The Flying Frenchman was one of the many ships commissioned by the French Angola Company, and over its 50 year lifespan it went from one of the most infamous pirate ships of the Caribbean to one of the Kingdom of France’s most respected anti-piracy ships of the Straights of Malacca

Henri’s ascendency to the throne coincided with the French Angola Company’s first acquisition in the Indian Ocean--two ports on the island of Madagasgcar. While trading had occurred between Madagascans and Europeans for decades, the constant conflicts between the coastal kingdoms and the warlords of the mountains had made any European settlement impossible. The French Angola Company solved this by sending 7,000 soldiers to the island to bring ‘peace’ to the island and to build wooden forts around two harbors. This news was greeted with great applause within the Louvre, and Henri responded to it by renaming the company the Royal East Indies Company, creating a law giving the company a subsidy of 5 million livres a year, and giving the new company the responsibility of finding trade in the Indian Ocean and in the Far East.

In order to fill this responsibility the REIC took on the same colonization strategy the Quebec Royal Company had--they took ‘central points’ under their direct control, using them as chokepoints for native traders. These strategic points had to be easily defensible while being central to the flow of trade.

The conquest of the Maldives, Ceylon, and Aceh

The Island Wars--during which the REIC conquered the Maldives island chain, the kingdoms of Ceylon, the Aceh sultanate and the tribes of the Andaman islands--occurred over the 1620s and led to a huge increase in the assets of the Royal East India Company. Administered by Captain Guillem de Saint Omer (the great grandson of the famous explorer) and the colonels of the War of Hispania, the wars featured an evolution of the strategies used by Van Rosen against the Portuguese. First, the REIC navy would destroy enemy fleets and enforce a blockade. Second, troops would land and would remain on the coastal areas while supported by the fleet, defeating the enemy’s standing army. Lastly, interior areas would be taken with the help of native allies, would would then be used as the nominal government of the new dependency.

This put the REIC in the perfect position to dominate the trade of the Indian Ocean, and soon the REIC was trading along the South China Sea. By 1629 the REIC dominated the silk trade and was providing naval support along the whole of the Chinese coast. Indeed, on the Fujian and Zhejiang coasts it was more common to see a representative of the REIC than a representative of the Ming Dynasty. This put the French in a precarious position when the ‘great crisis of the 17th century’ occurred. The collapse of the Ming Dynasty triggered the world’s first international intervention and, to the Chinese, began the Four Kingdoms period, a time of great upheaval and great innovation. In the next section I will discuss the history of China in the late 16th and early 17th and the beginning of the Four Kingdoms period.

Pretty good update for a mushified brain. If only France had been this insightful in OTL.

Mush for brains is a perfectly legit reason for slow updates.

So, France now has a major holdings in both North America/Canada, South America and Asia. Got any plans for Africa?

So, France now has a major holdings in both North America/Canada, South America and Asia. Got any plans for Africa?