Building a Nation - an Interactive British AAR

- Thread starter unmerged(260001)

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Excellent.

Now we shall see some interesting conflict between those two camps on foreign affairs for sure.

Now we shall see some interesting conflict between those two camps on foreign affairs for sure.

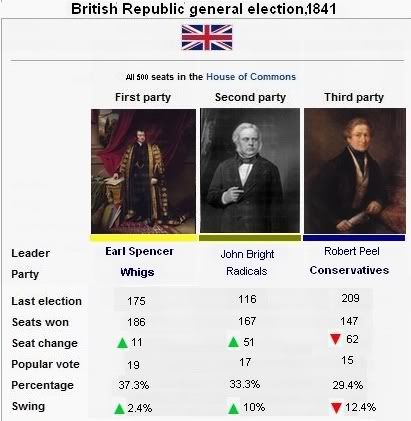

The Election of 1841

Following the effective collapse of the Whig-Radical alliance during the summer of 1841 a new election was called. It seemed that, after over five years of coalition, the two parties could no longer work together. In the sphere of foreign politics the Whigs were eager to once again play a major role on the world stage whilst the Radicals favoured a more pacifist approach and friendship with other Republics. There was also a fundamental disagreement on the future of the Republic. The alliance of 1836 had been formed at a time when the Whigs felt certain that Britain needed to reform itself or face destruction – by 1841 the Whigs felt that these reforms had been accomplished whilst the Radicals believed that the country still had a long way to go. These were the fundamental reasons for the breakup of the coalition.

But more pressingly two issues dominated the election – the future of the Atlantic Republic and of Ireland. In both situations Tories and Whigs agreed that Britain should take control over the states and in both situations the Radicals called for them to remain independent. Taking all this into account the shift of the Whigs to the right and to the Tories is unsurprising.

What was a surprise was the election result. Robert Peel’s more liberalised Tories slumped to electoral disaster and third place but into government whilst the Radicals were triumphant in their gain of 51 seats (just over 10% of the entire Parliament) but were shunted into the opposition.

Faced with either attempting to patch things up with the Radicals or look to a more centrist Tory party for support Prime Minister Spencer chose to unite with Peel’s Conservatives to form the new government.

The election oversaw a significant shift in Parliament that left only one party happy – the Whigs. The Radicals were disappointed to be out of government and the Tories to have lost so much of their presence. However, the Whigs secured a small gain (11 seats), became the largest party in Parliament and ensured a continuation in government under Whig leadership. Better still; the majority of the government was now significantly larger as the coalition controlled some 333 seats.

But the actual shift in voting patterns had occurred in a strange way as the furthest rightwing party had experienced a major fall in votes whilst the furthest leftwing party had experienced a major rise. This can be partly explained by the changed nature of the Whig party. In 1836 the Whig party had been very much in favour of quite major changes to Britain – it attracted votes from many who wanted this change but were wary of the Radicals. The Conservatives, meanwhile, attracted votes from those who were nervous of comprehensive reform and favoured a restoration of traditional institutions. In 1841 the Whigs no longer supported comprehensive reforms (believing Britain to have been reformed enough) – therefore a large number of former Tory voters shifted their allegiance to the Whigs. At the same time former Whig supporters who still wanted reform shifted to the Radicals.

Whatever the reasons for the shift in voting from right to left the new government would have to deal with the situation. In the first days after the results Robert Peel came within an inch of being overthrown by his party – his saviour was Prime Minister Spencer. At first many feared that Britain would be without a majority government – former Tory leader Wellington was quite outspoken in his opposition to an unequal alliance with the Whigs, after all, the Radicals had been treated with near contempt for much of the previous Parliament by the Whig leadership. Yet Spencer came to the Tories with an offer they could not refuse: in the economy a principle of the flexible use of tariffs, a promise not to further reforms to the constitution, a pledge to increase military spending and most importantly of all the British government would commit to an intervention in Ireland beginning within one year of the new Parliament. With a further promise that the Cabinet would be 50% Tory, Peel was saved as he entered into the coalition. In these early days differences were glossed over by goodwill, mutual distrust of Radicalism and the jingoistic desire to reclaim Britain’s most ancient of colonies.

The British electorate might have shifted to the left, but the government had taken a definite shift to the right

Following the effective collapse of the Whig-Radical alliance during the summer of 1841 a new election was called. It seemed that, after over five years of coalition, the two parties could no longer work together. In the sphere of foreign politics the Whigs were eager to once again play a major role on the world stage whilst the Radicals favoured a more pacifist approach and friendship with other Republics. There was also a fundamental disagreement on the future of the Republic. The alliance of 1836 had been formed at a time when the Whigs felt certain that Britain needed to reform itself or face destruction – by 1841 the Whigs felt that these reforms had been accomplished whilst the Radicals believed that the country still had a long way to go. These were the fundamental reasons for the breakup of the coalition.

But more pressingly two issues dominated the election – the future of the Atlantic Republic and of Ireland. In both situations Tories and Whigs agreed that Britain should take control over the states and in both situations the Radicals called for them to remain independent. Taking all this into account the shift of the Whigs to the right and to the Tories is unsurprising.

What was a surprise was the election result. Robert Peel’s more liberalised Tories slumped to electoral disaster and third place but into government whilst the Radicals were triumphant in their gain of 51 seats (just over 10% of the entire Parliament) but were shunted into the opposition.

Faced with either attempting to patch things up with the Radicals or look to a more centrist Tory party for support Prime Minister Spencer chose to unite with Peel’s Conservatives to form the new government.

The election oversaw a significant shift in Parliament that left only one party happy – the Whigs. The Radicals were disappointed to be out of government and the Tories to have lost so much of their presence. However, the Whigs secured a small gain (11 seats), became the largest party in Parliament and ensured a continuation in government under Whig leadership. Better still; the majority of the government was now significantly larger as the coalition controlled some 333 seats.

But the actual shift in voting patterns had occurred in a strange way as the furthest rightwing party had experienced a major fall in votes whilst the furthest leftwing party had experienced a major rise. This can be partly explained by the changed nature of the Whig party. In 1836 the Whig party had been very much in favour of quite major changes to Britain – it attracted votes from many who wanted this change but were wary of the Radicals. The Conservatives, meanwhile, attracted votes from those who were nervous of comprehensive reform and favoured a restoration of traditional institutions. In 1841 the Whigs no longer supported comprehensive reforms (believing Britain to have been reformed enough) – therefore a large number of former Tory voters shifted their allegiance to the Whigs. At the same time former Whig supporters who still wanted reform shifted to the Radicals.

Whatever the reasons for the shift in voting from right to left the new government would have to deal with the situation. In the first days after the results Robert Peel came within an inch of being overthrown by his party – his saviour was Prime Minister Spencer. At first many feared that Britain would be without a majority government – former Tory leader Wellington was quite outspoken in his opposition to an unequal alliance with the Whigs, after all, the Radicals had been treated with near contempt for much of the previous Parliament by the Whig leadership. Yet Spencer came to the Tories with an offer they could not refuse: in the economy a principle of the flexible use of tariffs, a promise not to further reforms to the constitution, a pledge to increase military spending and most importantly of all the British government would commit to an intervention in Ireland beginning within one year of the new Parliament. With a further promise that the Cabinet would be 50% Tory, Peel was saved as he entered into the coalition. In these early days differences were glossed over by goodwill, mutual distrust of Radicalism and the jingoistic desire to reclaim Britain’s most ancient of colonies.

The British electorate might have shifted to the left, but the government had taken a definite shift to the right

Not good, 50% Tories in the government. The Whigs are too generous. Soon they'll reintroduce slavery or something.

The British electorate might have shifted to the left, but the government had taken a definite shift to the right

It's good to see that politics keep their demented way

The reactionaries (Whigs and Tories alike) seek to defile freedom at every beck and turn. To think our new republic has turned to slaughter or Irish neighbors, like the monarchy before it.

Soldiers are we,

whose lives are pledged to Ireland,

Some have come

from a land beyond the wave,

Sworn to be free,

no more our ancient sireland,

Shall shelter the despot or the slave.

Tonight we man the "bearna baoil",

In Erin’s cause, come woe or weal,

’Mid cannon’s roar and rifles’ peal,

We’ll chant a soldier's song

Soldiers are we,

whose lives are pledged to Ireland,

Some have come

from a land beyond the wave,

Sworn to be free,

no more our ancient sireland,

Shall shelter the despot or the slave.

Tonight we man the "bearna baoil",

In Erin’s cause, come woe or weal,

’Mid cannon’s roar and rifles’ peal,

We’ll chant a soldier's song

Pfft. Great, so now we get to annex two sovereign republics without even a question of whether or not they even want to be annexed. Liberty for me, but not for thee. Let us prop up the ultra-sensitive southern American slaveholders who have begun to murmur of secession, why not!

Let us prop up the ultra-sensitive southern American slaveholders who have begun to murmur of secession, why not!

You are full of brilliant ideas. If we were to support the secessionists it would significantly reduce the power of our American rivals.

You are full of brilliant ideas. If we were to support the secessionists it would significantly reduce the power of our American rivals.

Yes, and while we support slavery abroad, why not reintroduce it at home too?

Seriously, the ways things are going I wouldn't be surprised if the Reactionaries suddenly proclaimed a personal union with some weird little despotic principality in central Germany, or something.

Yes, and while we support slavery abroad, why not reintroduce it at home too?

Don't be ridiculous. Everyone knows wage slavery is more profitable than chattel slavery.

Yes, and while we support slavery abroad, why not reintroduce it at home too?

Seriously, the ways things are going I wouldn't be surprised if the Reactionaries suddenly proclaimed a personal union with some weird little despotic principality in central Germany, or something.

I've been told that Ruritania looks lovely in this time of the year

Sigh...I'd hoped that the Whig/Tory alliance would avoid Ireland...ah well...

At least the people of the Atlantic Republic get their wish and will return to the nation...

Win some, lose some.

At least the people of the Atlantic Republic get their wish and will return to the nation...

Win some, lose some.

Not too bad. I can agree on the foreign and military policy, but I'm afraid that tarrifs will harm our economy. The strong popular support for the radicals also show that some further social reform may be needed to prevent social upheaval in the future. We don't want the radicals to be too radicalized, and while the elites may cry over ireland and america the mass of the people surely care more about their own freedom and daily bread.

However, I would like to congratulate Earl Spencer on a successful campaign and wish him the best of luck for the term.

However, I would like to congratulate Earl Spencer on a successful campaign and wish him the best of luck for the term.

The Second Parliament of the Republic of Britain - 1841-1847

As the new coalition settled down to the job of governing the Republic with a hefty majority of 83 seats several key changes to the budget were made. A 3% tariff was levied on all imported goods (to satisfy the protectionist Tory right) – this raised a much greater amount of money than had been expected and allowed for taxes on the middle income strata to be halved, taxes on the poorest to fall by 5% (these citizens bore most of the tax burden) and allowed for an increase in the military budget. All this on top of the investment in a new fleet of steamships.

During this early honeymoon period of the new government Prime Minister Spencer entertained the first visit of a foreign head of state to Britain in the history of the Republic as King Leopold I came to London to put pen to paper on a Treaty of Friendship with Britain. Whilst stopping short of an open military alliance the Treaty between the two Great Powers (Belgium having an industrial output only marginally lesser than France’s) ensured economic cooperation, a non-aggression pact and the first tentative motions of Britain returning to continental affairs. The British press seemed to gleefully greet the visit and the treaty as the end of British isolation from Europe.

Yet the new government’s honeymoon was not to last long. As Britain went to war with Ireland in a torrent of jingoistic enthusiasm and patriotism in the summer of 1842 the government reached its popular peak. Within a month the British Army had suffered a harsh defeat at Waterford – forcing the invasion force to be doubled in size. As the summer rolled on casualties on both sides started to escalate faster than anyone had expected. By the Autumn public opinion was sliding quickly towards an anti-war stance.

It was at this time that Feargus O’Connor exploded into the popular conscious. Before he had merely been a shadow cabinet minister within the opposition Radical Party, he would soon become even more significant that Party leader John Bright. Feargus was a part of a large Irish population that lived permanently in the major industrial cities of Britain – driven there in past decades by poverty and the chance of work. But unlike most of his fellow Irishmen O’Connor came from a well off background and was heavily involved in politics. A major figure within the Chartist movement of the 1830s he had since led the most extreme fringe MPs of the Radical Party. Whilst the Radical Party as a whole was anti-war John Bright had made sure to keep the party in check and prevent any major anti-war action for fear of alienating his party from the political mainstream. O’Connor ignored this and had started to build up an anti-war movement which mixed pacifism in foreign affairs with call for political change.

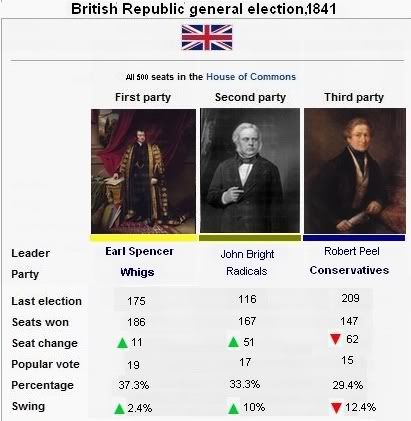

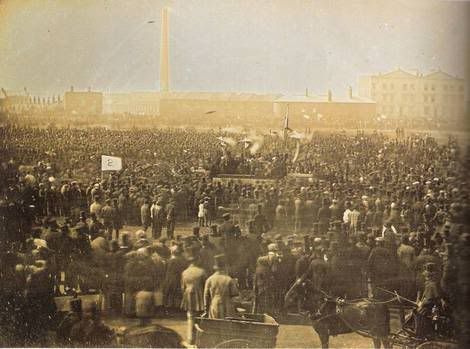

In November 1842 O’Connor organised an anti-war rally in Glasgow. The crowd largely consisted of Catholic factory workers and was seen as extremely militant and dangerous by local authorities. After clashing with opposing groups of workers – mostly pro-war and Protestant – O’Connor’s group started to grow rowdy and attacked a police station. After the attack on the police station the British authorities in the city panicked and sent out a call to a brigade of infantry stationed nearby. The soldiers confronted the protesters and in this tense situation one of them fired a shot. In the resulting massacre 37 protesters were killed.

To understand what happened next one must look at the incredible outpouring of anger across the European continent from late 1842 through 1843 and in placed into the following year. The period, sometimes called the Springtime of Nations or Springtime of the Peoples, marked a wave of revolutionary activity across the entire continent. Like so many cataclysmic events in European history it all began in France. By 1842 areas of France were starting to catch up with where Britain was a decade before – industrialisation, mass poverty, poor harvests, failure to reform and incompetent governance had turned much of the French people firmly against King Louis-Philippe. In October of 1842 mass demonstrations in Paris turned violent after clashes with troops and after several days of fighting on the streets King Louis was forced to withdraw from Paris. This remarkable triumph would lead to the spread of the revolution across the entire continent in the months afterwards.

From France the movement rapidly started to spread. In Austria the minorities – most notably the Hungarians – rose up against Habsburg rule, in the Italian states thousands fought for liberty and national reunification, but it was in Germany where things were most intense. More so than elsewhere in Germany many of the protests were mixed with socialism – particularly in the industrialised Rhineland. The Communist Manifesto had been published in the summer of 1842 and drew together many of the ideas of the socialist movement that had been growing in France and Germany around this time. The movement was so influential that between May and July 1842 the city of Cologne in the Rhineland was governed by a socialist council before Prussian troops re-entered the city and slaughtered the rebels.

Order would gradually be restored over the continent during 1843 as in France, Germany and Italy the armies of the old regimes restored order. Only in Austria did fighting linger on into 1844 and this was largely due to the greater focus of Hungarian, Slavic and Romanian rebels in the countryside. By the summer of 1844 the revolution was clearly at an end.

Within Britain much had changed during this time.

Following the massacre at Glasgow opposition to the war with Ireland and working class anger at the failure of the Republic to grant universal male suffrage or to improve working conditions in factories (two major aims of the British Revolution of the early 1830s) skyrocketed. Whilst the official stance of the Radical Party remained against violent action – John Bright constantly emphasised that the ballot box was the proper route to reform. Yet O’Connor and the Chartist left of the Party openly and unashamedly started to organise workers against the government. John Bright was left in an impossible position. If he gave any support to the Chartists and the protests then he would alienate the Party from the political mainstream and would almost certainly force the ‘Radical Whig’ wing of the Party out whilst forcing other sections of the Party’s right to reconsider their position. If he did not act then he might lose the Chartists and credibility as the representative of the British working class in Parliament.

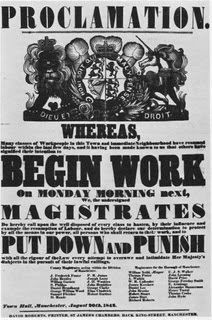

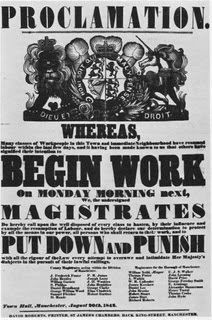

As the Chartist movement continued to increase radically in scope and influence the Radicals dithered and did nothing. Bright’s would finally be pushed to make a decision in February 1843 when Europe’s first true general strike was called. With workers across the country demanding universal suffrage, better conditions, freedom to gather in whichever Unions they wanted and many of them peace in Ireland (although by this stage this had become a lesser demand) hundreds of places of work were affected across the country with factories, mines and mills all having to close.

The reaction of the British government was hardly surprising – it planned to use force to nip this new phenomenon in the bud before it could become a real threat. Both the government at O’Connor’s Chartists (still officially a part of the Radical Party) looked to John Bright for support. Bright’s message to the Chartists couldn’t be clearer as he sent an ultimatum demanding that O’Connor either call for the strike to end of resign from the party. When he did neither both he and his supporters (some 47 of the 167 Radical MPs) were expelled from the party.

The strike lasted for approximately three weeks. In some parts of the country the workers were forced to return to work for economic reasons, in others the show of force by the government convinced them that it was better to go back, but in a few places (notably in South Wales) the workers attempted to fight back leading to a significant degree of bloodshed.

But by the middle of Spring the fight was over – O’Connor, many trade unionists and most leading Chartists faced arrest. From the outside it might have appeared that little had changed during that brief outburst of worker’s anger. But in reality British politics had been forever altered.

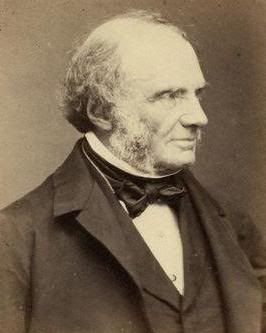

For one thing it came as near as makes no difference to bringing down the government. The violent response the government took to the General Strike and the arrest of so many persons involved in it afterwards greatly alienated the left wing of the Whig party. The refusal of the government to immediately release them once things died down finally pushed the reformists within the party to defect. Led by Earl Russell 72 of the Whig Party’s 186 MPs left the party. This left the government with a majority of just 11 members and made the Tories the larger coalition partner (although Spencer was allowed to continue as Prime Minister). Russell’s Whig rebels then joined together with the Radical Party (a move pioneered by the pro-Russell ‘Radical Whigs’) to form the Liberal Party. The Liberals were slightly stronger than the pre-Autumn 1842 Radicals had been but seemed to have a clearer message. The party would support reform to meet the demands of the workers (most notably the demand for universal male suffrage), continue to tout free trade in the economy and avoid grand Imperial adventures like Ireland. The Liberal Party was to be led by Earl Russell.

Through the rest of 1843 the Liberals would apply a significant degree of pressure on the government – eventually forcing them to release those imprisoned for their involvement in the General Strike.

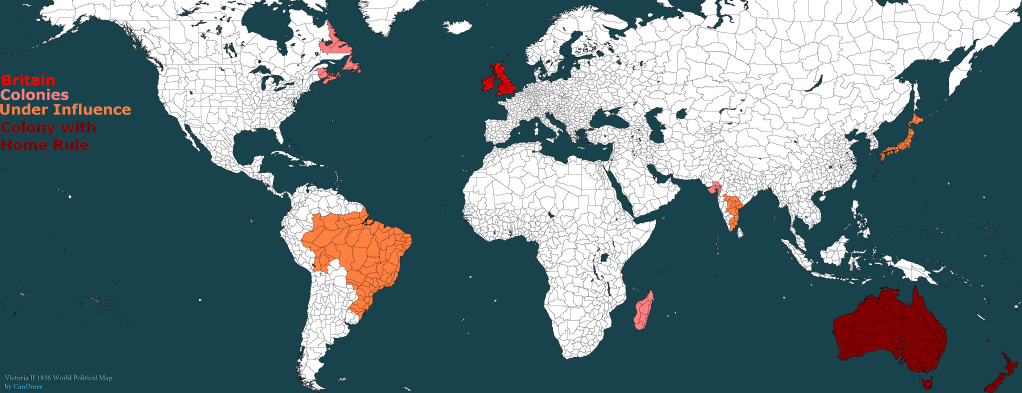

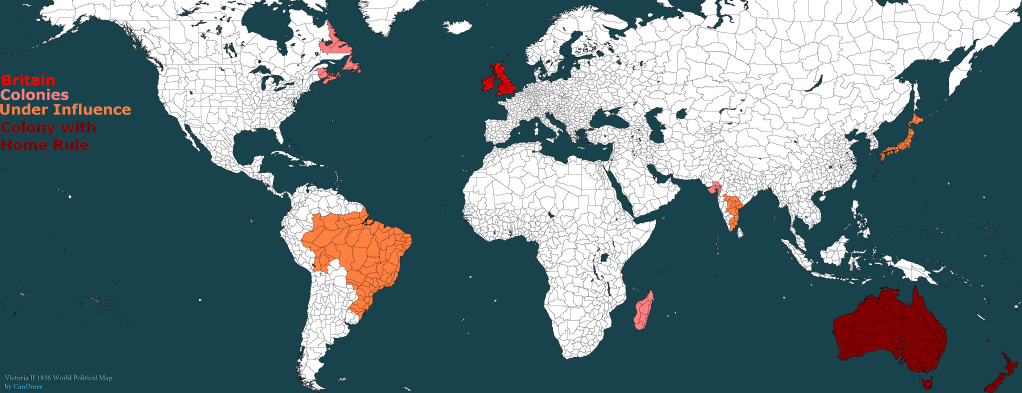

In international affairs from the Strike on to the end of the Parliament Britain pursued a policy of rampant Imperialism. In the late summer Ireland was finally annexed – following this the transfer of land back to its former British owners began. In January 1844 the Atlantic Republic was finally annexed by the British Empire. Rather than become a full part of the British Republic as it had wished the Atlantic Republic was instead turned into a sort of ‘special status’ colony. With its own elected council to manage much of its internal affairs and a governor from Britain (appointed by Parliament) to act in the name of the British state the Atlantic Provinces would enjoy a significant degree of autonomy. Later that year an impressive trade deal was set up with Brazil which gave British traders preferential treatment in return for training the Imperial Army and constructing the Brazilian Empire’s new navy.

In 1845 the British made their spectacular return to Indian politics. Invading Beroda and conquering Gujarat (providing access to vital cotton supplies as well as tobacco – then the 3rd largest import of Britain), then the Nizam of Hyderabad agreed to a series of treaties that gave Britain substantial trading and political influence in his great Empire (this providing access to an all important tea supply – by far Britain’s greatest import – as well as other important goods like cotton and dyes). Hyderabad had recently faced wars against the Dutch (who were beaten) and the French (who were victorious) so the protection of a European power was gratefully accepted.

Between 1844 and 1846 Britain and Australia rapidly grew together. The European population of Australia had never really stopped considering itself to be British, so it is perhaps unsurprising that they wilfully accepted a union with Britain. The province of Australia was given total self governance – certainly considerably more than the Atlantic Provinces. The only changes to Australia’s independence were: the loss of control over its own military (in truth a bonus as Australia had previously had next to no standing army – this merely gave it Britain’s military protection), the loss of control over foreign policy (again not much of a loss), the change in its official status (perhaps even a positive for a people who considered themselves British in the first place).

As the new coalition settled down to the job of governing the Republic with a hefty majority of 83 seats several key changes to the budget were made. A 3% tariff was levied on all imported goods (to satisfy the protectionist Tory right) – this raised a much greater amount of money than had been expected and allowed for taxes on the middle income strata to be halved, taxes on the poorest to fall by 5% (these citizens bore most of the tax burden) and allowed for an increase in the military budget. All this on top of the investment in a new fleet of steamships.

During this early honeymoon period of the new government Prime Minister Spencer entertained the first visit of a foreign head of state to Britain in the history of the Republic as King Leopold I came to London to put pen to paper on a Treaty of Friendship with Britain. Whilst stopping short of an open military alliance the Treaty between the two Great Powers (Belgium having an industrial output only marginally lesser than France’s) ensured economic cooperation, a non-aggression pact and the first tentative motions of Britain returning to continental affairs. The British press seemed to gleefully greet the visit and the treaty as the end of British isolation from Europe.

Yet the new government’s honeymoon was not to last long. As Britain went to war with Ireland in a torrent of jingoistic enthusiasm and patriotism in the summer of 1842 the government reached its popular peak. Within a month the British Army had suffered a harsh defeat at Waterford – forcing the invasion force to be doubled in size. As the summer rolled on casualties on both sides started to escalate faster than anyone had expected. By the Autumn public opinion was sliding quickly towards an anti-war stance.

It was at this time that Feargus O’Connor exploded into the popular conscious. Before he had merely been a shadow cabinet minister within the opposition Radical Party, he would soon become even more significant that Party leader John Bright. Feargus was a part of a large Irish population that lived permanently in the major industrial cities of Britain – driven there in past decades by poverty and the chance of work. But unlike most of his fellow Irishmen O’Connor came from a well off background and was heavily involved in politics. A major figure within the Chartist movement of the 1830s he had since led the most extreme fringe MPs of the Radical Party. Whilst the Radical Party as a whole was anti-war John Bright had made sure to keep the party in check and prevent any major anti-war action for fear of alienating his party from the political mainstream. O’Connor ignored this and had started to build up an anti-war movement which mixed pacifism in foreign affairs with call for political change.

In November 1842 O’Connor organised an anti-war rally in Glasgow. The crowd largely consisted of Catholic factory workers and was seen as extremely militant and dangerous by local authorities. After clashing with opposing groups of workers – mostly pro-war and Protestant – O’Connor’s group started to grow rowdy and attacked a police station. After the attack on the police station the British authorities in the city panicked and sent out a call to a brigade of infantry stationed nearby. The soldiers confronted the protesters and in this tense situation one of them fired a shot. In the resulting massacre 37 protesters were killed.

To understand what happened next one must look at the incredible outpouring of anger across the European continent from late 1842 through 1843 and in placed into the following year. The period, sometimes called the Springtime of Nations or Springtime of the Peoples, marked a wave of revolutionary activity across the entire continent. Like so many cataclysmic events in European history it all began in France. By 1842 areas of France were starting to catch up with where Britain was a decade before – industrialisation, mass poverty, poor harvests, failure to reform and incompetent governance had turned much of the French people firmly against King Louis-Philippe. In October of 1842 mass demonstrations in Paris turned violent after clashes with troops and after several days of fighting on the streets King Louis was forced to withdraw from Paris. This remarkable triumph would lead to the spread of the revolution across the entire continent in the months afterwards.

From France the movement rapidly started to spread. In Austria the minorities – most notably the Hungarians – rose up against Habsburg rule, in the Italian states thousands fought for liberty and national reunification, but it was in Germany where things were most intense. More so than elsewhere in Germany many of the protests were mixed with socialism – particularly in the industrialised Rhineland. The Communist Manifesto had been published in the summer of 1842 and drew together many of the ideas of the socialist movement that had been growing in France and Germany around this time. The movement was so influential that between May and July 1842 the city of Cologne in the Rhineland was governed by a socialist council before Prussian troops re-entered the city and slaughtered the rebels.

Order would gradually be restored over the continent during 1843 as in France, Germany and Italy the armies of the old regimes restored order. Only in Austria did fighting linger on into 1844 and this was largely due to the greater focus of Hungarian, Slavic and Romanian rebels in the countryside. By the summer of 1844 the revolution was clearly at an end.

Within Britain much had changed during this time.

Following the massacre at Glasgow opposition to the war with Ireland and working class anger at the failure of the Republic to grant universal male suffrage or to improve working conditions in factories (two major aims of the British Revolution of the early 1830s) skyrocketed. Whilst the official stance of the Radical Party remained against violent action – John Bright constantly emphasised that the ballot box was the proper route to reform. Yet O’Connor and the Chartist left of the Party openly and unashamedly started to organise workers against the government. John Bright was left in an impossible position. If he gave any support to the Chartists and the protests then he would alienate the Party from the political mainstream and would almost certainly force the ‘Radical Whig’ wing of the Party out whilst forcing other sections of the Party’s right to reconsider their position. If he did not act then he might lose the Chartists and credibility as the representative of the British working class in Parliament.

As the Chartist movement continued to increase radically in scope and influence the Radicals dithered and did nothing. Bright’s would finally be pushed to make a decision in February 1843 when Europe’s first true general strike was called. With workers across the country demanding universal suffrage, better conditions, freedom to gather in whichever Unions they wanted and many of them peace in Ireland (although by this stage this had become a lesser demand) hundreds of places of work were affected across the country with factories, mines and mills all having to close.

The reaction of the British government was hardly surprising – it planned to use force to nip this new phenomenon in the bud before it could become a real threat. Both the government at O’Connor’s Chartists (still officially a part of the Radical Party) looked to John Bright for support. Bright’s message to the Chartists couldn’t be clearer as he sent an ultimatum demanding that O’Connor either call for the strike to end of resign from the party. When he did neither both he and his supporters (some 47 of the 167 Radical MPs) were expelled from the party.

The strike lasted for approximately three weeks. In some parts of the country the workers were forced to return to work for economic reasons, in others the show of force by the government convinced them that it was better to go back, but in a few places (notably in South Wales) the workers attempted to fight back leading to a significant degree of bloodshed.

But by the middle of Spring the fight was over – O’Connor, many trade unionists and most leading Chartists faced arrest. From the outside it might have appeared that little had changed during that brief outburst of worker’s anger. But in reality British politics had been forever altered.

For one thing it came as near as makes no difference to bringing down the government. The violent response the government took to the General Strike and the arrest of so many persons involved in it afterwards greatly alienated the left wing of the Whig party. The refusal of the government to immediately release them once things died down finally pushed the reformists within the party to defect. Led by Earl Russell 72 of the Whig Party’s 186 MPs left the party. This left the government with a majority of just 11 members and made the Tories the larger coalition partner (although Spencer was allowed to continue as Prime Minister). Russell’s Whig rebels then joined together with the Radical Party (a move pioneered by the pro-Russell ‘Radical Whigs’) to form the Liberal Party. The Liberals were slightly stronger than the pre-Autumn 1842 Radicals had been but seemed to have a clearer message. The party would support reform to meet the demands of the workers (most notably the demand for universal male suffrage), continue to tout free trade in the economy and avoid grand Imperial adventures like Ireland. The Liberal Party was to be led by Earl Russell.

Through the rest of 1843 the Liberals would apply a significant degree of pressure on the government – eventually forcing them to release those imprisoned for their involvement in the General Strike.

In international affairs from the Strike on to the end of the Parliament Britain pursued a policy of rampant Imperialism. In the late summer Ireland was finally annexed – following this the transfer of land back to its former British owners began. In January 1844 the Atlantic Republic was finally annexed by the British Empire. Rather than become a full part of the British Republic as it had wished the Atlantic Republic was instead turned into a sort of ‘special status’ colony. With its own elected council to manage much of its internal affairs and a governor from Britain (appointed by Parliament) to act in the name of the British state the Atlantic Provinces would enjoy a significant degree of autonomy. Later that year an impressive trade deal was set up with Brazil which gave British traders preferential treatment in return for training the Imperial Army and constructing the Brazilian Empire’s new navy.

In 1845 the British made their spectacular return to Indian politics. Invading Beroda and conquering Gujarat (providing access to vital cotton supplies as well as tobacco – then the 3rd largest import of Britain), then the Nizam of Hyderabad agreed to a series of treaties that gave Britain substantial trading and political influence in his great Empire (this providing access to an all important tea supply – by far Britain’s greatest import – as well as other important goods like cotton and dyes). Hyderabad had recently faced wars against the Dutch (who were beaten) and the French (who were victorious) so the protection of a European power was gratefully accepted.

Between 1844 and 1846 Britain and Australia rapidly grew together. The European population of Australia had never really stopped considering itself to be British, so it is perhaps unsurprising that they wilfully accepted a union with Britain. The province of Australia was given total self governance – certainly considerably more than the Atlantic Provinces. The only changes to Australia’s independence were: the loss of control over its own military (in truth a bonus as Australia had previously had next to no standing army – this merely gave it Britain’s military protection), the loss of control over foreign policy (again not much of a loss), the change in its official status (perhaps even a positive for a people who considered themselves British in the first place).

See how horrible an idea annexing Ireland was? Even a fair number of people HERE strongly disagreed with it to the point of rioting and striking! Pfft, sure, "caring and loving brother" indeed, going out and killing the lot o' them and massacring the protesters here! I'm sure we'll be caring for them and loving them even more when we're engineering famines again.

EDIT: Also, was that Socialist group taking power in Cologne thing a reference to Tommy's AAR?

EDIT: Also, was that Socialist group taking power in Cologne thing a reference to Tommy's AAR?

Last edited:

This "Communist Manifesto" seems quiet interesting, along with the strikes conducted by the Irish at home...... Maybe we should implement some of these policies into our government system? Of fund a party based on these principles?

I second Seek75. Tommy was the first that came to mind when I read that part.

Hurrah! We are regaining our lost brethren and our lost honour bit by bit!

Hurrah! We are regaining our lost brethren and our lost honour bit by bit!

If the Chartrists found their own Party I might vote for them. Would be interesting to see Britain under Socialism.

- Status

- Not open for further replies.