Sagaria Invicta - A Sergal Mega-Campaign AAR

- Thread starter Sriseru

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Starting Info

- Sergals are the creation of Mick Ono and Kiki-UMA and are part of the Vilous setting.

- In addition to the CK2 save converter mod, I also have several other mods installed for increased historical realism (which, for example, prevent the kind of insane blobbing you often see in vanilla games), as well as my own sergal mod.

- The sergal species is OP militarily by design, but their unique population mechanic can also benefit the AI, as sergals settled in a province will boost its manpower, sailors, and defensiveness based on their population size.

- Because the Mercantile Clans (vassal Merchant Republics) of Sagaria ended up dominating trade, racked in a crap ton of cash every month, and established a direct trade route to India in the 14th century, I decided to give Sagaria some bonuses to reflect this. I placed a triggered province modifier in the capital of each Mercantile Clan that combined provided several trade bonuses, as well as four extra Merchants to redirect trade from western India to the Baltic. Is this a bit cheat-y? Yes, but it makes a lot more sense to have them in this alternate world than not to. Besides, these bonuses will be lost later down the line in the campaign, and they also end up having a very interesting effect on another country bordering the Baltic Sea.

- This AAR is not going to focus entirely on Sagaria, but more on the sergal species and the world as a whole.

- I’m going to be making stuff up a lot in order to create an interesting history, using the events of the game as a guideline. I won’t make up something that contradicts anything that happens in the game, however.

- Non-Ironman, since I needed the console for debugging purposes, as well as to fix any in-word weirdness.

- Although the core of this scenario is extremely fantastical and unrealistic, I still want to try and make it somewhat believable.

- This is the second part of a mega-campaign spanning from CK2 to EU4 to Vic2, but it will have a hefty epilogue that will chronicle this alternate history right up to this current year. I decided to skip HoI4 because a)I’ve never played that game, and b)HoI4 didn’t seem like the right kind of game to pick up where Vic2 will leave off.

.jpg)

Art by @KlebinhoBaby from twitter

.jpg)

Art by Anna Khudorenko

Table of Contents

A Brief History of Medieval Sagaria

Sergals During the Middle Ages

Sagaria in 1444 AD

The World in 1444 AD

---

Renasceria and Reformation - 1450-1602 AD

Exploration and Trade - 1354-1611 AD

Sagaria and the East - 1444-1700 AD

Purple Phoenix - 1289-1720 AD

Rise of Mercia - 1418-1802 AD

Sweden and the Conquest of the New World - 1527-1700 AD

The Childcare and Scientific Revolutions - 1550-1700 AD

The Rise of Capitalism - 1361-1700 AD

Age of Reason and Industry - 1700-1750 AD

Masters of War - 850-1775 AD

The Great Revolution - 1750-1755 AD

Annabel Bergman - 1734-1771 AD

A New Europe - 1760-1815 AD

Last edited:

A Brief History of Medieval Sagaria

Pre-Christian Sagaria (476-919 AD)

The origins of sergalkind is one of the greatest mysteries of the world. Prior to the late 5th century, they seemingly did not exist at all, as not even a hint of them can be found in the archeological record. And between the 5th century and the 10th century, all we have of them is their own highly mythologized oral history, as well as written records from people who encountered them.

Sergals first entered the annals of recorded history in 546 AD, during Queen Jusul’s Great Raid, when her expeditionary force made their way into the Byzantine Empire. They left a great impression on the Greek- and Latin-speaking world, and from the information they managed to glean from the event, they came to refer to the sergals as the “Sagari.”

The great empires and kingdoms of southern Europe had also left a big impression on the sergals. They were in awe of them, but also felt threatened by their capabilities.

Christianization of the Sergals (919-1021 AD)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Christian scholars eventually debated on whether the sergals had the souls of beasts or of rational beings. Because sergals clearly possessed all of the mental qualities of a human, the consensus that was reached was that they, like humans, possessed rational souls and thus could accept the message of Christ.

As for the sergals themselves, because they were permanently surrounded by human realms who viewed them as alien and monstrous, they were desperate to establish some kind of commonality in order to ease tensions and secure their future existence. As Christianity spread northward, the religion was seen as a means to achieve this.

In 926 AD, the sergal King Jadak was baptized and then led the effort to convert the rest of his people to Christianity. Pope Innocentius II formally crowned Jadak as the King of Sagaria, the Latin name for their land, which Jadak readily adopted.

Sagarian Golden Age (1021-1250 AD)

The communal and meritocratic social structure of Sagaria allowed the Kingdom to Christianize and modernize at a remarkable pace. Furthermore, the sergals’ natural speed, mobility, strength, and endurance made them excellent soldiers, being famously able to outrun and outmaneuver light cavalry with ease. In 1021 AD, Europe got to witness just how powerful Sagaria and its military had become when Pope Innocentius IV requested that Queen Sifel I depose King Thomas of France. At the time, France was one of the greatest powers in Europe and considered to be second only to the Byzantine Empire. The Sagarian armies of Sifel I beat the French military, and they did it easily. By the time Queen Sifel I had fulfilled the Pope’s request, France had shattered into several smaller kingdoms and duchies. This event ushered in the Sagarian Golden Age.

Having seen just how powerful the Sagarian military was, rulers throughout Europe sought to acquire their own sergal armies. Some provided immigrant sergals with land in exchange for military service, whereas wealthier rulers simply hired Sagarian mercenaries. Seeing the demand and wanting to offset their military expenditures, the rulers of Sagaria decided to rent out their armies. This turned out to be even more successful than anticipated, as Sagaria was not just offsetting the cost of its armies, but was actually making a good profit.

The Catholic Church sought to use Sagaria’s military supremacy to fight infidels, and so they launched several crusades, primarily against the Muslim world. Sagaria’s sovereigns and commanders led each and every one of the crusades to victory, and brought the lion’s share of the loot back home with them. Between this and renting out its armies, Sagaria grew to become exorbitantly wealthy, and its rulers used this wealth to foster culture and learning.

In addition to serving as the sword and shield of Christianity, sergals came to be viewed as especially pious. This was because they possessed a highly communal mindset, a strong inclination for optimism, as well as an almost supernatural intuition. Because of these qualities, their holy men and women appeared to their human counterparts to have an incredibly strong connection to God. It was because of this that so many sergals ended up becoming Popes and saints.

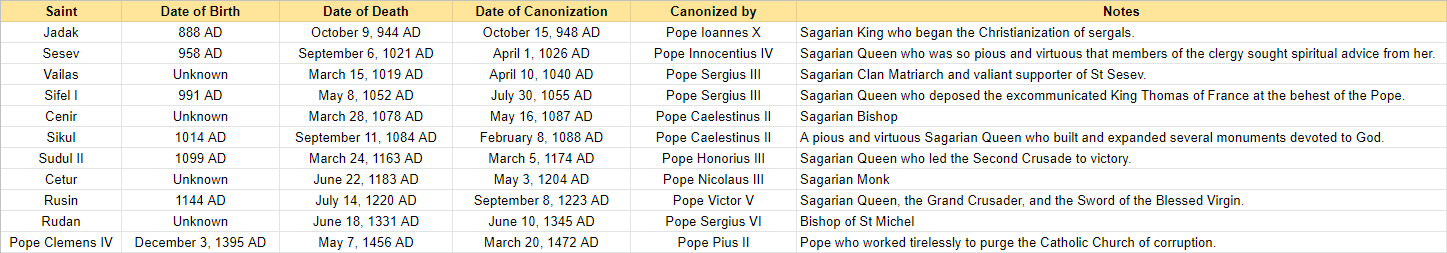

Sergal Popes in the Middle Ages

Sergal saints of the Middle Ages

Following its purchase from Sweden in 1107 AD, the Mecklenburg region was settled by sergals who founded Clan Edutirou. It did not take them long before they realized that Mecklenburg’s Baltic coast to the north, close proximity to where the Baltic met the North Sea, and its connection to the Elbe river made their clan perfectly situated for mercantile endeavors. Thanks to the sponsorship and investments made by the Sagarian sovereigns, the Clan of Mecklenburg rapidly developed into the dominant mercantile power in the Baltic.

As its wealth grew, the Mecklenburg Clan expanded into the North Sea. Only 50 years after being founded, Clan Edutirou controlled an extensive trading network throughout the northeastern Atlantic Ocean. They purchased coastal land all over Northern and Western Europe, where they founded trading cities and settled new sergal clans loyal to them.

Following the fall of the Byzantine Empire during the infamous Third Crusade, the Mecklenburg Clan seized the island of Crete in order to gain a strong foothold in the Mediterranean. The sergals of Crete eventually grew too powerful for the Clan Edutirou to control, and in 1209 AD the Cretan Clan broke off from them, although they still remained part of Sagaria. From then on, The Mecklenburg Clan was forced to deal with the Cretans as partners and potential rivals, but this wouldn’t last.

The Rise of the Mercantile Clans (1250-1444 AD)

The Mecklenburg Clan and the Clan of Crete became collectively known as the Mercantile Clans, and thanks to the incredible wealth they were bringing in, Sagaria grew increasingly more urbanized. However, it also grew more corrupt as the Mercantile used their power and influence in order to further and protect their own interests. As they undermined the meritocratic system that had served Sagaria so well, the Kingdom’s leadership grew weak.

The Mercantile Clans launched their greatest undertaking in the mid-14th century. After acquiring the Sinai Peninsula, in large due part to the sizeable sergal population who had settled there following the Fourth Crusade, they invested an enormous amount of resources and manpower to construct a flat, 7.3 meter wide paved stone road connecting the Mediterranean with the Suez Gulf, intended to serve as a highway for trade goods. One of the local sergal clans, Clan Felan, was given control of Sinai. Subordinate to the other Mercantile Clans, Clan Felan nevertheless received everything they needed to build a massive fleet of wagons and merchant ships so that they could transport trade goods in bulk from the east to the coast of the Mediterranean.

However, the ambitious plans of the Mercantile Clans had to be put on hold when the Black Death began to spread like wildfire throughout Europe, West Asia, and North Africa in 1345 AD. As it turned out, sergals were completely immune to the deadly plague, and although many sergals outside of Sagaria were killed by mobs of humans looking for scapegoats, the Mercantile Clans benefited immensely from it. All of their human rivals, such as Genoa and Venice, were significantly weakened by the Black Death, and the Mercantile Clans took the opportunity to fill the void left by them. Once the plague had passed, the Mercantile Clans of Sagaria were unquestionably the dominant trading power in the known world. They even managed to persuade the Pope to grant them a monopoly on all maritime trade east of the Mediterranean.

With the Black Death behind them, the Clan of Sinai set up trade routes to East Africa, Arabia, Iran, and India. As Clan Felan brought in huge amounts of spices to Europe, the Mercantile Clans and Sagaria as a whole grew exorbitantly wealthy. However, Clan Felan saw only a small fraction of this wealth, as they were not permitted to sell the goods themselves, only deliver them to the northern ports of Sinai, where Mecklenburg traders gave them their payment and loaded the goods onto their own ships. In 1372 AD, the Clan of Sinai attempted to defy the Mecklenburg Clan, who responded by bribing a Sagarian army to occupy Sinai and butcher its Clan Matriarch and her family. Clan Felan did not dare defy them after that, and instead sought to maximize the flow of trade goods in order to increase their cut of the profits.

In 1441 AD, the Clan of Sinai purchased a substantial plot of land on the southeastern coast of India from the Maharaja of Tamilakam. And in 1444 AD, they established a sergal colony there, thus setting the stage for a new era of trade and colonialism.

Last edited:

Probably more of a gilded age, given that the Mercantile Clans have effectively taken control of Sagaria.Seems like there might be another golden age pretty soon.

Just got done with the CKII segment. Hype to see where things go in EUIV!

- 1

Sergals During the Middle Ages

Prior to their conversion to Christianity, sergals rarely ventured outside of Sagaria, as the vast majority of humans viewed them as monstrous. This began to change following their Christianization, but Europe’s attitude towards them shifted completely following the Sagarian-French war of 1021 AD. Not only did the sergals show off their military prowess against one of the most powerful kingdoms of Europe, but they also demonstrated their civility—they did not attack noncombatants, those who surrendered were spared, and no captives were taken. Because of this, many European rulers sought to hire sergal mercenaries to fight in their wars, and Sagaria took advantage of this by renting out its own armies, which helped offset their costs and allowed them to gain more battle experience.

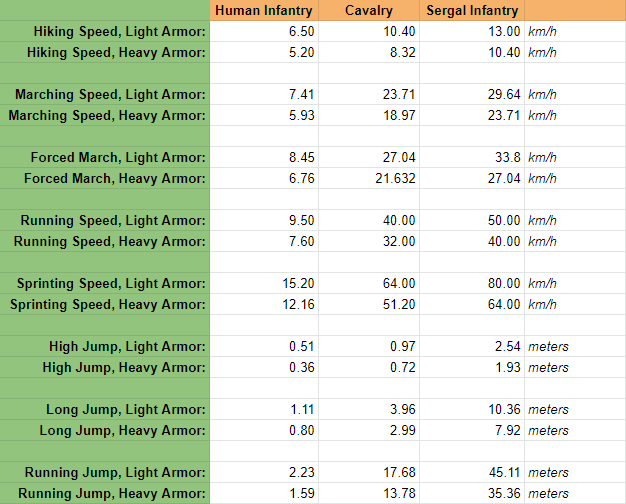

Mobility comparison between human infantry, cavalry, and sergal infantry.

The prevalence of Sagarian mercenaries in Europe motivated human rulers to acquire their own sergal troops. They offered land to sergal clans in exchange for military service. These immigrants became a new and unique facet of Medieval society. They were essentially a kind of caste, albeit a highly esteemed one, with most serving their lords as elite troops.

Unlike knights, who ruled over and were supported by the labor of peasants, and could therefore spend most of their life training and honing their martial abilities, the sergal caste had to be largely self-sufficient as they had to cultivate their own land. As such, most were farmers, but unlike human peasants, they were exempt from paying taxes or providing labor for their lord, thus freeing up time and energy that could be spent on honing their martial skills. In wartime, the youngest and oldest sergals stayed behind to tend the fields, as well as child rearers and the least competent warriors.

However, even with their own sergal units, the human militaries were unable to contend with the all-sergal Sagarian army. But in wars between two human realms, elite sergal units could be the deciding factor between victory and defeat, and thus came to be seen as a necessity in Medieval warfare.

In addition to serving their lords as elite troops, many non-Sagarian sergals ended up in religious positions as well. Their powerful intuition, communal mindset, and strong tendency for optimism made them perfectly suited as spiritual advisors and clergymen. This is why so many sergals ended up becoming bishops, Cardinals, Popes, and saints. Religious thinkers at the time were of the opinion that the ancestors of the sergal people had sacrificed their human visage in exchange for a special connection to God.

Over time, the sergals who emigrated from Sagaria were culturally assimilated. In most of Europe, they gradually lost their clan structure and instead adopted the family structure used in their new homeland, but even so they would always remain tightly knit with their extended family members. Because of this, several distinct sergal noble families eventually arose in Europe.

Sergal migrations and the widespread employment of sergal mercenaries resulted in the spreading of certain aspects of Sagarian culture. By the Late Middle Ages, a purely agnatic system of inheritance fell out of favor in much of Europe, and although there was still a strong preference for male successors, it became more acceptable for human women to inherit land and titles.

The martial talents and perceived piety of sergals led to them either founding or becoming the heads of several holy military orders, the most famous being the Knights Templar. Both the Knights Templar and the Knights Hospitaller were founded by especially devout Sagarian mercenaries following the First Crusade.

Not all sergals remained in Europe. Many clans settled lands won from the Crusades, but there were some who went as far east as Central Asia, and as far south as West Africa. Some of these distant clans would abandon Christianity and adopt the local religion, but due to their isolation they would often struggle with inbreeding.

When the Black Death ravaged Europe, it turned out that sergals were completely unaffected by it due to their unique genetic makeup. Unfortunately, as people grew more fearful and irrational, many humans blamed the plague on them, which led to persecutions and killings. Some sergal communities who had been granted land by human lords were expelled, forcing them to migrate elsewhere. The Church condemned these actions, of course, but there was little they could do to calm the masses or reign in the political ambitions of kings and nobles.

Although the Black Death did not directly affect Sagaria or other sergal populations, it did adversely affect them indirectly. By the Late Middle Ages, Sagaria had become so urbanized that it had become reliant on food imports to supplement their own agricultural output. As the plague raged across Europe, those imports stopped, resulting in famine. It is estimated that roughly 5% of the sergal population died as a result of the famine and the persecutions, which is tiny compared to the 30-60% of the human population in Europe who were killed by the Black Death.

The Black Death did end up having a surprising but lasting influence on the Catholic Church. Many of the human members of the clergy and monastic orders who actively helped their communities ended up dying, and as such most of the ones who survived the plague were cowardly or selfish to some degree. As a result, the sergal members of the clergy and monastic orders were seen as much more virtuous and Christ-like than their human counterparts, which strengthened the ties the Catholic Church would have to sergalkind. More than half of the College of Cardinals were sergals only a decade into the Black Death, and beginning with Pope Innocentius V’s accession in 1352 AD, the Catholic Church would have a string of sergal Popes for little over two centuries.

Sergal demographics in 1450 AD. Sergals make up the minority of the population in yellow areas, and the majority in green areas.

Sagaria in 1444 AD

The Known World

Territorial Extent of Sagaria

In 1444 AD, the Kingdom of Sagaria had a vast maritime empire spanning throughout the Baltic, Northeast Atlantic, Mediterranean, Persian Gulf, Arabian Sea, and India. The Mercantile Clans of Mecklenburg, Crete, and Sinai made the Kingdom exorbitantly wealthy due to nearly holding a monopoly on eastern trade goods.

Additionally, Sagaria had a large number of semi-enclaves in the form of trading cities all over Europe. Normally, these kinds of territories would be absorbed by their surrounding realms via conquest or treaty, but Sagaria is unique in retaining these autonomous cities up to this day.

Sagaria proper was highly urbanized, being comparable to Northern Italy at this time. The Kingdom stood out from most of Europe in that they had never adopted feudalism nor serfdom. Instead they organized themselves into clans, with each clan ruling over its own territory with some autonomy. The clans raised all children communally and provided them with a public education through church-run schools. As the children grew, they were either assigned jobs befitting their abilities and dispositions, or provided with a higher education if they were gifted enough. Not only did this result in an almost universal literacy rate, albeit at a very basic level, but it also provided the clans and Sagaria as a whole with capable leaders. Upon reaching adulthood, all sergals in Sagaria were required to serve five years in the military, and once they had completed their mandatory service, those who had excelled the most were offered positions as professional soldiers or officers.

The clans of Sagaria were not permitted to maintain their own armies. Instead, the Kingdom had a standing military which owed its allegiance to the sovereign. This was ensured by rotating where each army was stationed on an annual basis, and because they recruited wherever they were stationed, the armies were all composed of a mixture of soldiers from different clans, which helped ensure that they were loyal to the crown first and foremost. Additionally, professional military personnel were forbidden from owning land, and any land they owned before joining were returned to their clans. Instead, they were entirely provided for by the sovereign in order to further ensure their loyalty.

The military, in particular the commanders, wielded a great degree of political power, however, as they were the ones who appointed the sovereign and kept her in power. Typically, they would appoint someone from their own ranks, unless an exemplary civilian caught their eye. Of course, the Mercantile Clans exercised an even greater degree of political power through bribery and backroom deals, thanks to their incredible wealth.

Sagaria was also unique in that they rented out some of their armies to serve as mercenaries for other Christian realms. The most famous of these was the “Sagarian Guard” employed by the Pope. Not only did this provide their military with battle experience, but it also served to improve diplomatic relations while also making a nice profit for the Kingdom.

- 1

The World in 1444 AD

Scandinavia

Sagaria had maintained a good relationship with the Scandinavian countries for most of its history, especially Sweden. The only exception to this is Denmark, who viewed them as a rival at best and a threat at worst.

As for the Swedes, they have never forgotten how the Sagarian Queen Sudul I went above and beyond to not only drive out the invading Burtas from Sweden during the First Crusade, but also protect the natives from her fellow crusaders. Although she came to be despised in her homeland, the pact of peace that Sudul I formed with King Bertil I of Sweden following the conclusion of the First Crusade has been honored by both Kingdoms. Since that time, many sergals settled Sweden as well as other parts of Scandinavia.

Rusland, Sagaria’s northeastern neighbor, was the youngest country within the Nordic cultural sphere, having begun as a tiny Finno-Norse kingdom on the Baltic coast. As Rusland grew, it attracted a large number of Sagarian immigrants, and as a result its culture evolved into a fusion of Finnish, Norse, and Sagarian.

Although Iceland has been under Norwegian rule for most of its history, its distance from the mainland has allowed it to enjoy a great deal of autonomy. Sergals began to immigrate to Iceland during the Black Death, and at this point they make up a little over half of the island’s population.

The British Isles

The two most powerful realms in the British Isles were Scotland and England, but the latter suffered from instability and rebellions throughout the High and Late Middle Ages. There were sizable sergal populations in several coastal areas in the British Isles, particularly on the island of Great Britain.

The Duchy of Mercia broke off from England in 1418 AD, and although it was tiny, it had a large sergal population and was even ruled by a sergal noble family, and thus could punch way above its weight class.

Central and Western Europe

Much of Central and Western Europe at this point was a patchwork of small but mutually hostile realms. The realms between Sagaria, Bavaria, Burgundy, and Austrasia made up the Holy Roman Empire, which by now was but a shadow of its former self. Bavaria is little more than a regional power. Although France never recovered from the Sagarian-French war of 1021 AD, it was nevertheless a potent middle power by 1444 AD, and held influence over England and some of its smaller neighbors. Burgundy, on the other hand, was wealthier and more of a major power, as was Galicia.

The Mediterranean

By 1444 AD, North Africa had been thoroughly converted to Catholicism, the only exception being Northeast Africa, which had remained Coptic. The Papal States had at various points in time ruled over most of North Africa, but by 1444 AD their holdings had shrunk. Even so, as the head of the biggest religion in the world, the Pope held a significant amount of influence over the Catholic world.

Ever since the fall of the Byzantine Empire in the Third Crusade, the realms in its former territories had all dreamt of restoring it, while also struggling with their new identities. Greek remained as the common tongue throughout the Balkans and Anatolia. Among these realms, Thrace and Moesia stood out as they had abandoned their Eastern Orthodox roots and instead embraced Roman Catholicism.

The Steppe and Central Asia

The dominant force in the Eurasian Steppe and Central Asia were the Mongols. They invaded China in the early 13th century, before conquering almost the entirety of Central Asia and the Iranian Plateau, bringing with them Buddhism to the Muslim and pagan lands. When Batu—the grandson of Genghis Khan and last Khagan of a united Mongol Empire—died, the Mongols split into three Khaganates: the Golden Horde, the Ilkhanate, and the Moghul Khanate. Like the Mongol Empire before them, the Golden Horde and Moghul Khanate continued to dominate and thrive in Central Asia, even in 1444 AD.

West Asia

The Ilkhanate, one of the three successor states of the Mongol Empire, controlled much of the Iranian Plateau, but over time the ruling Mongols gradually assimilated into the local cultures. By 1444 AD, the Khaganate had shattered into several smaller kingdoms, and although Buddhism has remained as the most dominant religion in the region, most of it is now under the rule of the Bedouin Hussayn dynasty.

Following the Christian conquest of the Arabian peninsula in the Eighth Crusade, the new realm that had been established there shattered into mutually hostile Crusader kingdoms and duchies. In the chaos, the Nasrids, a Catholic Bedouin dynasty, arose and came to control much of the peninsula.

West Africa

After centuries of onslaught by Christianity and the Buddhist Mongols, the light of Islam was put out in West Asia and North Africa. By 1444 AD, West Africa was its last bastion. In the wake of the Crusades, countless Muslim noble families, scholars, traders, and Imams fled to West Africa, changing the cultural makeup of the region.

India

By 1444 AD, India was divided amongst several Buddhist kingdoms, with the most powerful being Karnata, Malwa, Rajputana, Jambays, and Guge. The Sagarian Mercantile Clans began trading directly with the Indian kingdoms in 1361 AD, and by 1444 AD they had established a colony on the southeastern coast and their influence was beginning to be felt throughout the subcontinent.

- 1

Hooray! This AAR is one of the ones I've been most interested in.

Also, that is a LOT of border gore.

Also, that is a LOT of border gore.

- 1

So if I understand it correctly Hussayns are the Bedouins, who control Buddhist Persians?By 1444 AD, the Khaganate had shattered into several smaller kingdoms, and although Buddhism has remained as the most dominant religion in the region, most of it is now under the rule of the Bedouin Hussayn dynasty.

- 1

The Hussayns are a Buddhist Bedouin kingdom. The rulers, as well as most of the populace are all Buddhist Bedouins.So if I understand it correctly Hussayns are the Bedouins, who control Buddhist Persians?

Interesting... So Buddhism and Catholicism are the main religions of the world?The Hussayns are a Buddhist Bedouin kingdom. The rulers, as well as most of the populace are all Buddhist Bedouins.

I have one technical question: How is CK2 single Buddhism converted into it's several denominations in EUIV?

- 1

Yep, Catholicism and Buddhism dominate this world.Interesting... So Buddhism and Catholicism are the main religions of the world?

I have one technical question: How is CK2 single Buddhism converted into it's several denominations in EUIV?

As for your question... I'm not entirely sure. I think it's based on either region or culture, since in this campaign India, Indochina, and parts of Iran follow the Theravada denomination of Buddhism, whereas Central Asia, the Eurasian Steppe, and pretty much all of the territories conquered by the Mongols follow the Vajrayana denomination.

- 1

Renasceria and Reformation - 1450-1602 AD

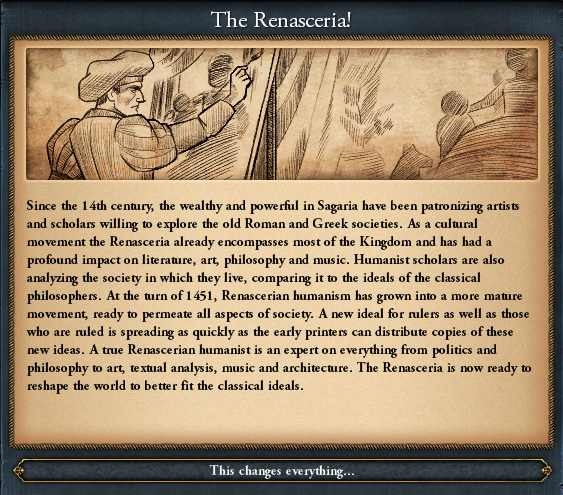

The 15th and 16th centuries saw the beginning of art and learning flourishing in many parts of Europe. The focal point of this “Renasceria” was the Kingdom of Sagaria, where the Mercantile Clans were bringing in an enormous amount of wealth, which its social elite then spent patronizing artists, architects, scholars, and inventors. The term “Renasceria” refers to a “rebirth” of interest in the legacy of ancient Greece and Rome, which began in Sagaria in the 14th century. However, it wasn’t until the middle of the 15th century that the Renascerian movement truly matured and spread outward to the cities and royal courts of Europe.

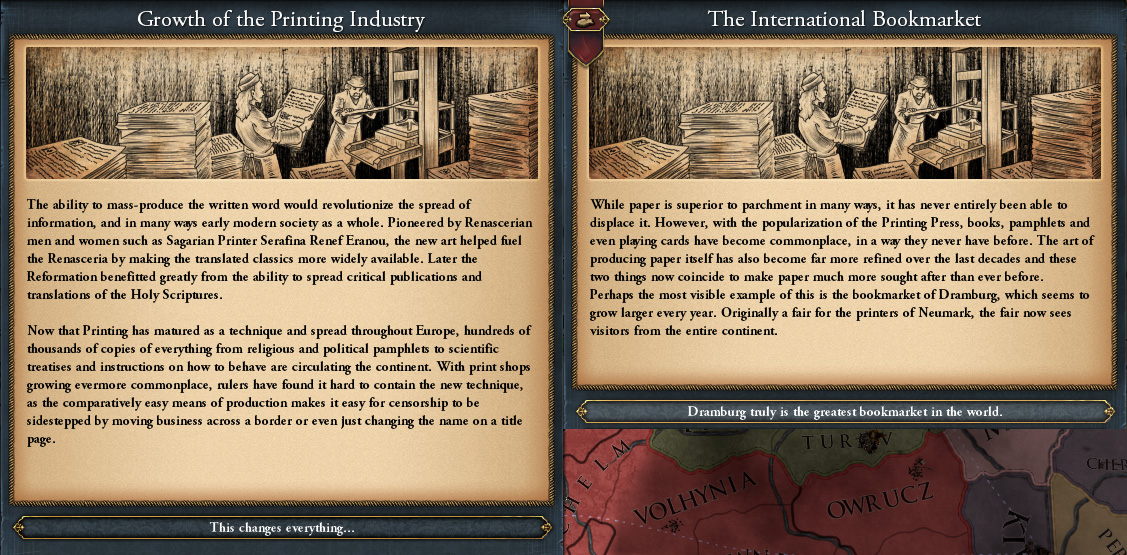

Of course, Renascerian ideas wouldn’t have spread as quickly they did had it not been for the invention of the movable-type printing press by Serafina Renef Eranou, a Sagarian goldsmith. Because of its practice of communal childrearing and public education, the Kingdom of Sagaria had a near universal literacy rate. However, overall reading comprehension was abysmal when compared to today, due to the lack of standardized texts and writing conventions. This began to change with the invention of the printing press, as the rulers of Sagaria quickly recognized the value of the device and invested a great deal of wealth into it. The wider availability of texts and a growing interest in their contents led to a sharp increase in reading comprehension throughout Sagaria. Within the span of only a few decades, printing and papermaking became a major industry in Sagaria, and this helped fuel the Renascerian movement.

The Renascerian movement was also partially fuelled by the increasing availability of coffee due to the Mercantile Clans’ trade and colonization in the east. Coffeehouses sprang up all over Sagaria in the early 16th century, and later elsewhere in Europe. They became popular meeting places where people would gather to drink coffee, have conversations, play board games, listen to stories and music, and discuss news and politics. Thus the coffeehouse served as a melting pot for ideas, many of which were then disseminated thanks to the printing press. Of course, when these coffeehouses were first established, there were several European rulers who viewed them as places for political gatherings where dangerous ideas could be discussed and spread. This resulted in coffeehouses being banned in various European realms in the 16th and early 17th centuries.

In Sagaria, the curiosity, inventiveness, and drive for excellence of the Renascerian men and women produced countless feats of art and engineering. They learned from and emulated the achievements of antiquity and improved upon them. This was most noticeable in the area of architecture. One of the first great accomplishments of the Renascerian movement was the great dome built for the Basilica of Saint Mary the Star of the Sea, which exceeded anything built in the ancient world and was seen as a near miraculous feat of engineering. Domes such as that of the Basilica of Saint Mary were constructed as a crowning feature of the most ambitious Renascerian buildings in Sagaria, such as the Basilica of the Holy Spirit, while Greco-Roman columns, arches, and statues were ubiquitous in other architectural works such as the City Hall of Lufec, the Cathedral of Saint Rusin the Sword of the Blessed Virgin, the Cathedral of Saint Cecilia, as well as the Red Palace, which was built as the residence of the Sagarian sovereign.

Similarly, painters and sculptors took a great deal of inspiration from the ancient world, while innovating and building upon the techniques that had come before. In the late 15th century, Sagarian artists such as Falas Narea Degou and Isac Netar Atani developed the use of highly realistic linear perspective. This was part of a larger Renascerian trend towards realism in art, with many artists striving to depict the beauty of the visual world with absolute precision.

Digital recreation of a mechanical lion originally built in 1498 for the Matriarch of Clan Edutirou.

With their large disposable incomes, the social elite of Sagaria developed an appetite for clever inventions, both to amuse themselves and to show off their wealth. They sponsored a large number of master craftsmen and inventors. The contraptions built were more often than not impressive but impractical. An example of this was the land yacht—a small ship on wheels designed to sail on land—although it could build up impressive speeds, its abysmal maneuverability and reliance on even terrain made it useless as anything other than a pleasure craft. Another impressive, but at the time largely impractical, invention was an early hot air balloon created by Sofia Esila Edutirou, which worked by inflating the balloon with smoke and hot air from a fire built on the ground until it flew away. It could only carry a single passenger, however, and could only remain airborne for less than two minutes. By far, the most popular contraptions made for amusement and entertainment were automatons built to resemble people or animals. These ranged in complexity from mechanical spiders that, after being wound up by a key, were propelled forward on wheels while their legs moved up and down, to life-sized programmable musicians that were powered by the flow of water.

The sponsorship from wealthy Sagarians did end up producing several practical inventions, however, the most notable one being the movable-type printing press. Spring-driven clocks were another major invention, which made timepieces more accurate and allowed them to reliably mark minutes. This also made it possible to build clocks small enough to be conveniently carried around. Multiple innovations were also made with gunpowder weapons, such as longer, lighter, more efficient, and more accurate cannons, as well as wheelock and flintlock firearms.

Outside of Sagaria, the major centers of Renascerian cultural activity were Frisia, the southern part of Sweden, as well as the prosperous city-states of Italy. These places had grown rich from banking, trade, and manufacture, and they spent their wealth on cultural luxuries out of civic pride or to advertise the power and status of their rulers.

Major Renascerian architectural works in Sweden included the Brageborg Castle, a grand palatial complex built as a royal residence for King Brage III in the early 16th century, as well as the Dagskrona Cathedral, which was built later that century. Those in the Italian city-states included the Cathedral of Saint Lawrence and the Palazzo Acardi in Florence. And in Frisia there was the City Hall built in Lohn to show off the port city’s prosperity.

The Renascerian movement also began to question long-held truths received from the revered ancients. The discovery of the New World in the beginning of the 16th century challenged the geographical works of Ptolemy, which were corrected by European explorers and mapmakers. Similarly, the dissection of corpses allowed the ideas of the ancient Greek physician Galen to be surpassed.

One of the earliest and most notable Renescarian rulers of Sagaria was King Kadak II, who ruled Sagaria in the late 15th century and was known for his intellect and scholarly pursuits, and for sponsoring learned people. After finding the astronomical works of Queen Sifel II, which had been published in the early 13th century and deemed heretical due to asserting that the sun was the center of the solar system, Kadak II was so amazed by her theories, observations, astronomical predictions, and mathematics, that he decided to take advantage of the recently invented printing press to popularize her work. Naturally, this upset the Church, as it contradicted the current Christian view that the Earth was the center of the universe. However, Kadak II refused to be deterred and in 1478 AD he sent a delegation of Sagarian scholars and diplomats to meet with Pope Benedictus VI in Rome. They explained Sifel II’s heliocentric model in detail and expertly answered any questions or concerns he raised regarding it. The popular view of history is that the delegation’s presentation and arguments were so convincing that they managed to persuade the Pope to approve of the model. However, in reality, the Pope’s positive response was almost certainly due to political reasons. Unlike in Sifel II’s time, Sagaria in the 15th century controlled most of the seats in the College of Cardinals and provided the Catholic Church with the lion’s share of its income through tithes, donations, and bribes. As such, Pope Benedictus VI must have been well aware of the danger of antagonizing the sovereign of Sagaria.

“We cannot deny the truths that are so evident in the Lord’s creation.” - Pope Benedictus VI

This event set an important precedent in how the Catholic Church would handle the Renasceria and later Scientific Revolution. Pope Benedictus VI and his successors would support both movements and work to reconcile the more radical new ideas with Catholic doctrine. Of course, this support for the sciences became one of the major grievances that the Reformist movement would end up having against the Catholic Church.

English Protestants burning literature viewed as heretical.

The beginnings of the Reformation can be traced to the latter half of the 15th century, when a number of Renascerian thinkers began to criticize the Catholic clergy for its corruption and called for a return to a purer form of faith. Most historians, however, would agree that the Reformation truly began in the year 1514 AD, when English friar Joseph Ainsley began to circulate pamphlets which criticize the Church and the papacy, with a focus on doctrinal policies about purgatory, particular judgment, the authority of the pope, and the adoption of heretical ideas such as heliocentrism. Then, in 1517 AD, Ainsley published a translated bible in English. Thanks to the printing press, his writing flooded the British Isles and later much of the rest of Europe.

Ainsley’s challenge to Catholic doctrine won him many followers and supporters from all ranks of society. Following his excommunication in 1516 AD, Ainsley decided to set up his own independent church. The idea of breaking from the Catholic church was very appealing to many rulers in Western Europe and Germany, as it would allow them to establish their own state church that was firmly under their control. In 1525 AD, King Edmund III of England declared his support for the Protestant movement, seized church lands to provide funds for his war against Mercia, and made the Ainslian church the English state church. Wales similarly adopted Protestantism a few years later and reformed its own church along Ainslian lines, as did a small number of German states.

As the 16th century dragged on, a growing number of German states and Western European realms came to adopt Protestantism. Scotland embraced the Protestant movement in 1545 AD, as did Frisia in 1548 AD, Mercia in 1563 AD, France in 1574 AD.

In 1528 AD, a preacher by the name Guilhem Laudin converted Haut-Poitou along Ainslian lines. However, Laudin disagreed with some of Ainsley’s views, and he began to lead his followers in a more radical, anti-hierarchical direction. By 1531 AD, Laudinism had developed into its own distinct movement, and by 1543 AD it had become the state religion of Poitou. Similar Reformed faiths had been embraced in various parts of Iberia by 1571 AD, and in Denmark in 1587 AD.

Initially, the Catholic church responded to the Reformation by excommunicating those who rebelled against it. However, by 1547 AD it became clear that it could not crush the movement, and so the Pope called for an ecumenical council to be held in the Italian city of Trent. Between the years 1547 to 1549 AD, three sessions were held where bishops and other church authorities discussed how to handle the Reformation, how to mend the problems within the Catholic church itself, as well as what changes needed to be made to strengthen Catholicism both theologically and politically.

Ultimately, the Catholic church settled on a conciliatory position towards the Protestants and it began to take steps to reform itself for the better, which resulted in a strong Catholic resurgence. The private approach to confessions would be retained and the practice of public heresy trials were banned. The Catholic church also commissioned the Roman Catechism, a compendium that aimed to expound doctrine and to improve the theological understanding of the clergy. Additionally, the practice of celibacy was rescinded as the council could not find sufficient support for it in the holy scripture. Finally, the tradition of mysticism within Catholicism was retained. This Counter-Reformation proved highly successful, as it significantly slowed down the tide of the Reformation, which is largely considered to have ended in the early 17th century.

Religion in Europe in 1510 AD.

Religion in Europe in 1620 AD.

- 1

I decided to go more for a world history approach (well, maybe European history would be more accurate) rather than the typical national history approach at this point in the AAR. As such, rather than each "chapter" being entirely sequential like in the CKII part, I decided to have each chapter cover some aspects of the era. This is mostly because it's more fun and interesting for me to write the AAR this way. Hopefully, it'll still be enjoyable for you to read.

- 1

First daughter of the church fell into heresy!

P.S.: What does "renasceria" means? Does it mean "renaisscance" in sergal?

P.S.: What does "renasceria" means? Does it mean "renaisscance" in sergal?

- 1

.png)