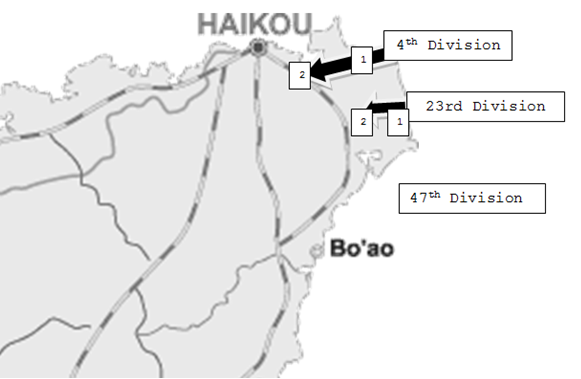

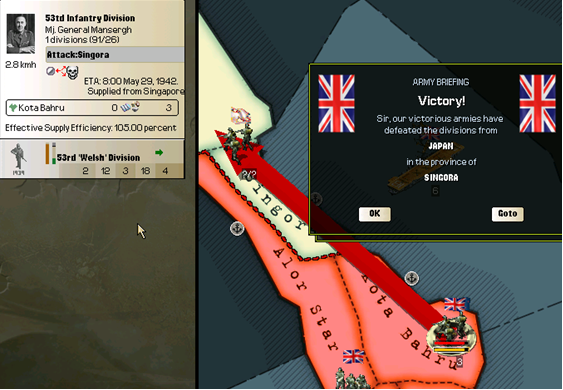

Belsay et al showing good initiative--keep the advance going, keep the pressure on, keep the Japanese off balance--thankfully no dallying on the beaches. Add in RN fire support and no Japanese air activity and this show has a chance after all.

The King's First Minister - a UK AAR

- Thread starter Le Jones

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Corking update. I hope the invasion works, but then again, it means that means the advance will only continue somewhere else.

Chapter 199, off ‘E’ Beach, Wenchang, Hainan, 17 May 1942

The British and Australian ships off the beach heard the sounds of the distant bombardment; the shock of the explosions shook the waiting warships and attracted crowds of curious sailors. Hurriedly despatched signals broke the news; the Japanese counterattack had commenced with terrifying ferocity. Supported by Japanese aircraft who flayed the British infantrymen with impunity, the Japanese Army tore into the wavering 47th Division. By lunchtime, after four hours of fighting, it was all over and the Londoners of the 47th were in panicked flight towards the waiting Royal Navy.

Lieutenant General (Acting General) Sir Henry Maitland Wilson, KCB, GBE, DSO, Second in Command Fourth Army, an important man in the highest reaches of the British Army, stood and stared impotently at the tired, defeated line of troops shivering their way back onto the transports. Above them, watching and encouraging, were the lucky ones, those who had already been lifted from the doomed beachhead at ‘E’ Beach and those who were now showered, fed, changed and beginning the long process of rebuilding the shattered 47th Division. Seeing one private, his left arm a mangled, useless stump and his face scarred on the left cheek Wilson, an undemonstrative man, clenched his fist and pounded the guardrail helplessly. He saw a Royal Navy destroyer move inshore and lift the survivors from a medical detachment from the beaches. ‘E’ Beach was quiet now, it’s appetite for British blood sated after two horror-filled days of tragedy and disaster. Wilson, sensing that he was required elsewhere, turned to go inside.

“How bad is it?” Wilson asked this of the officers clustered round the sickbay bed where a captain of the Royal Navy, bed-bound until the shrapnel wounds in his chest either finished him off or were removed, gave his report.

“Sir,” the captain began, his breath bubbled with blood, “frankly it is over. The Japanese have moved heavy artillery into the town and are pummelling the beaches. Every attack seems to run into formidable defences. And that damned waterway...” his voice trailed off.

“Could you tell me,” Wilson said with an infectious calm.

“It’s a natural harbour, and they can ferry men from side to side whilst we are pinned on the beaches.”

“How many Japanese?”

“We estimate at least six divisions’ worth, perhaps more. The locals are doing what they can to hinder the enemy, but with Japanese reprisals...”

“...I understand,” Wilson said simply. “Is there any good news?” He asked this to all of them.

An RAF officer, one of Park’s men from Malaya Command, stepped forward. “Our bombers have confirmed that your diversion was entirely successful. ‘not entirely sure what your Army and Navy types would say, but we can confirm that the diversion on the mainland has captured Leizhou and is already driving towards Zhanjiang. And our pilots report that that city is ablaze.”

“And what does that mean?” Wilson asked this is a calm, kindly voice.

“Conclusion? The Chinese rising has been entirely successful. And most of the Jap divisions are trapped on Hainan.”

“Having been tipped off about our assault there.” Wilson said as he considered this report. He turned to his own staff. “Is this confirmed?”

“Yes Sir,” his Chief of Staff replied.

“And what is your opinion on continuing the attack on Hainan?”

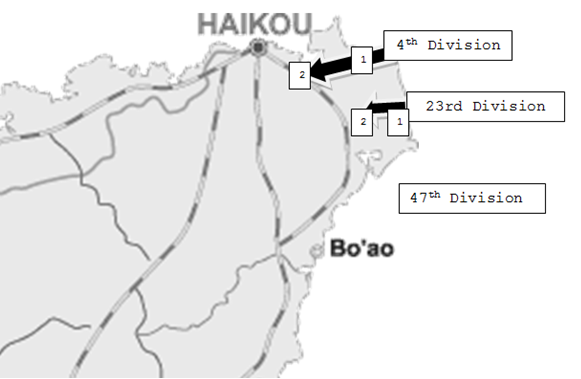

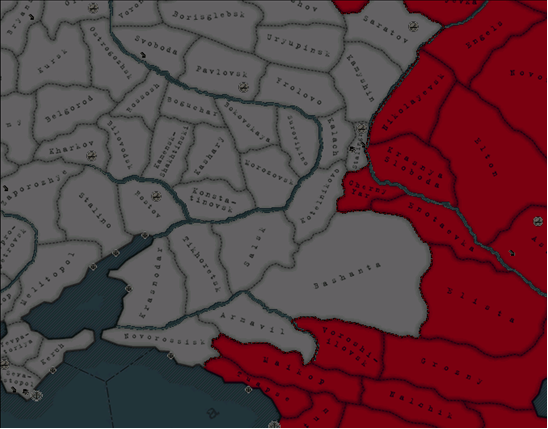

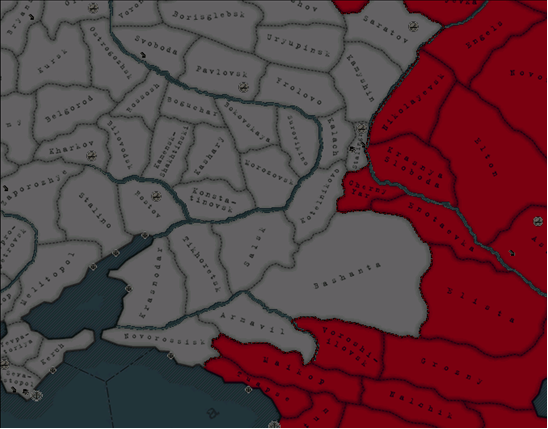

“Well Sir,” the Chief continued, “Fourth Division are nearly at Haikou; they were first in and overwhelmed the Jap defences before they had a time to organise themselves. The map shiows progress on day one and on day two. Twenty-third are still pushing forward; they’ve abandoned ‘D’ Beach and are relying on ‘C’ Beach, but they’ve defeated the Jap second line and are trying their best to come up to Fourth Division’s left flank...”

“..but?”

“I doubt that they can do it, Sir. That nice empty area where they could set up Corps HQ? It’s a bloody chain of marshlands and paddy fields. Every tree-line is a defensive point for the enemy. I don’t think that Fourth can count on the Twenty-third.”

“And the poor Forty-seventh I’ve seen,” Wilson said with resignation. “Any chance of re-positioning them to support the Twenty-third?”

“No Sir,” the injured Royal Navy officer mumbled. “It’ll take days to reorganise them.”

“Tell me, what are the conditions like for the men ashore?”

“Terrible,” the Chief of Staff replied. “Fourth Division will have to halt soon and Twenty-third are running out of ammunition and fresh water.”

“The enemy?”

The RAF officer nodded. “We can see that the Japanese have organised themselves defensively. Three divisions of infantry are moving up from ‘E’ Beach to threaten the Twenty-third. We’re trying our best to harry them but the Japanese air defences remain intact.”

“And,” the Chief of Staff, wanting to push the meeting along added, “Twenty-third are already very heavily engaged.”

“What about the other three divisions?”

The RAF officer grimaced. “Most of them are facing Fourth Division, though we have noticed a brigade moving here,” he jabbed at a chart for the gap between Fourth Division’s exposed left flank and the front of Twenty-third division.

Wilson closed his eyes. “When does General Brooke arrive?”

Another Royal Navy officer looked at his notes. “Tomorrow night, with the Army HQ and a few divisions. The Australians and the rest of the Army two days after that.”

Wilson was a brave man, and he knew that if he landed more men on Hainan he would reinforcing failure. The division on the mainland was achieving success, but would soon be horribly overwhelmed as the inevitable Japanese counter-attack developed.

“The Forty-seventh will land to support the Fifty-fifth, effective immediate. I want you to send a note to General Morgan at ‘C’ Beach. I’m calling off the landings on Hainan. Fourth Division to retire to ‘B’ Beach.” He turned to the Royal Navy contingent. “Can you get them off?”

They all nodded. Wilson closed his eyes. “I accept full responsibility for this of course,” he said quietly. “Could one of you get to the Fifty-fifth?”

The Chief of Staff nodded. “Message, Sir?”

“That Fourth Army is on the way. Tell them to keep pushing on, and that the Morgan’s Corps, followed by the Army, will reinforce them from tomorrow.”

The meeting concluded, Wilson returned ‘up top’ to view the burning coastline of Hainan. In the distance, the beach now to the South, Wilson looked at the burning port and the narrow entrance to the Ba Gate Wan waterway.

The decks were crowded with tired and injured infantrymen, men who relaxed with relief as Wilson waved away their attempts to rise to their feet or to salute him. In the distance, the plumes of smoke marking the position where Britain’s great ‘turning point’ had stalled and then failed terribly, lay an island, an island that Wilson hoped with a rare violence that he would never see again. The battle of Hainan was over.

[Game Effect] – Longbow, the diversion aside, is a bloody and tragic failure.

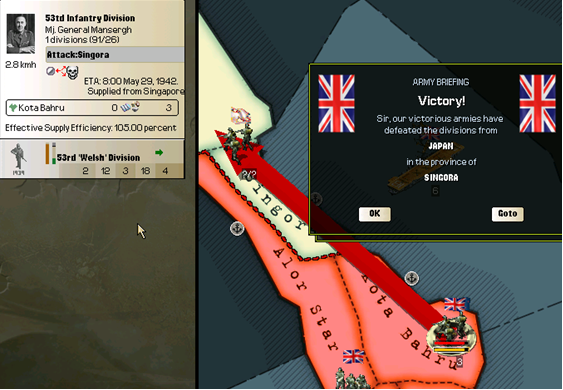

I’ve told you about the game – I landed the 3 INF divisions. Well, not a lot was going in the Far East at that point and I was busily taking screenies of the war in Russia. So when my 3 INF turned out to have engaged a dozen jap divisions you can see why the result was a setback, though the diversion on the Chinese mainland worked as there was virtually nothing to stop my 1 Mot division as it rumbled ashore. Simply put, when playing the game the Jap AI put everything in Southern China on Hainan and I was sloppy (this entire AAR is based on one of my early games of HOI2 DD) hence the disaster.

Yet another setback for the British led part of the war, and I feel that I must explain why (in AAR terms). The build-up to this, and the landings themselves, are based on British/Free French efforts against Dakar and Madagascar, both of which were badly planned and led. Both of those campaigns were marred by poor intelligence on the enemy forces, a total lack of secrecy amongst the planning officers, and a failure to take responsibility amongst senior officers. All of this is in evidence here: Morgan, the man with knowledge of the planning of this engagement, is ashore with his men, leaving the bewildered Wilson to arrive and try to save the landings. His decision, to concentrate on the mainland and allow Hainan to be blockaded, is probably the best decision of the entire operation and shows that whilst Wilson wasn’t a fantastic general, he was a competent, humane officer with the courage to make difficult choices. He reinforces success, not failure, and the remnants of V Corps are lucky to have Wilson at the tiller. They never had a great chance of victory, but with their few advantages squandered away, largely at the planning stages, the brave but doomed efforts of the British infantry are in vain. Expect questions to be asked of Pound (who was the senior advocate in the military for the landings) and the War Office.

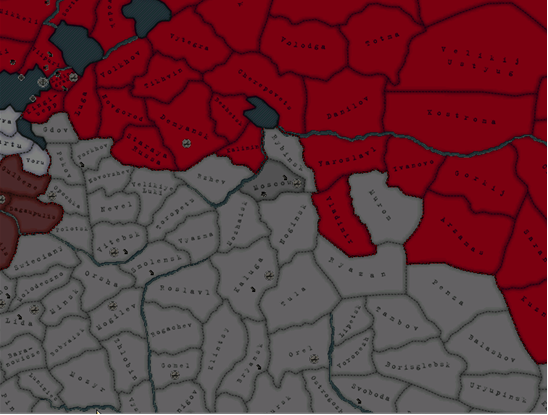

If Hainan, both in the game and the story, has one strategic crumb to be gained, it is this: with 12 INF divisions now pinned on an island surrounded by the massed fleets of the Commonwealth, the efforts of Auchinleck in Burma/Yunnan and the armies pushing into Siam from Burma/Malaya now have a chance. For those interested, prior to completing this post I did a quick ‘no fog’ and Indochina is virtually empty.

Trekaddict: A prophetic comment, mon brave

Enewald: The Dieppe comparison is certainly an interesting one. At least RN dominance of the seas saves V Corps.

El Pip: Well, 4th and 23rd Divisions do adequately, but the Londoners of 47th are the first dominos to fall. The divisional landing points are widely separated, certainly more than in Normandy 1944, and so this inability to provide mutual support could be a vital factor.

Kurt_Steiner: We’re in ‘or else’ territory now!

Zhuge Liang: You are proved correct Sir!

DonnieBaseball: A bit like our hopes of overcoming the US in the World Cup, sadly not.

Sir Humphrey: An interesting comment, as essentially you are correct: capturing Hainan merely gives the Auk and his men a better chance. It was a bold plan but is now undone.

The British and Australian ships off the beach heard the sounds of the distant bombardment; the shock of the explosions shook the waiting warships and attracted crowds of curious sailors. Hurriedly despatched signals broke the news; the Japanese counterattack had commenced with terrifying ferocity. Supported by Japanese aircraft who flayed the British infantrymen with impunity, the Japanese Army tore into the wavering 47th Division. By lunchtime, after four hours of fighting, it was all over and the Londoners of the 47th were in panicked flight towards the waiting Royal Navy.

Lieutenant General (Acting General) Sir Henry Maitland Wilson, KCB, GBE, DSO, Second in Command Fourth Army, an important man in the highest reaches of the British Army, stood and stared impotently at the tired, defeated line of troops shivering their way back onto the transports. Above them, watching and encouraging, were the lucky ones, those who had already been lifted from the doomed beachhead at ‘E’ Beach and those who were now showered, fed, changed and beginning the long process of rebuilding the shattered 47th Division. Seeing one private, his left arm a mangled, useless stump and his face scarred on the left cheek Wilson, an undemonstrative man, clenched his fist and pounded the guardrail helplessly. He saw a Royal Navy destroyer move inshore and lift the survivors from a medical detachment from the beaches. ‘E’ Beach was quiet now, it’s appetite for British blood sated after two horror-filled days of tragedy and disaster. Wilson, sensing that he was required elsewhere, turned to go inside.

“How bad is it?” Wilson asked this of the officers clustered round the sickbay bed where a captain of the Royal Navy, bed-bound until the shrapnel wounds in his chest either finished him off or were removed, gave his report.

“Sir,” the captain began, his breath bubbled with blood, “frankly it is over. The Japanese have moved heavy artillery into the town and are pummelling the beaches. Every attack seems to run into formidable defences. And that damned waterway...” his voice trailed off.

“Could you tell me,” Wilson said with an infectious calm.

“It’s a natural harbour, and they can ferry men from side to side whilst we are pinned on the beaches.”

“How many Japanese?”

“We estimate at least six divisions’ worth, perhaps more. The locals are doing what they can to hinder the enemy, but with Japanese reprisals...”

“...I understand,” Wilson said simply. “Is there any good news?” He asked this to all of them.

An RAF officer, one of Park’s men from Malaya Command, stepped forward. “Our bombers have confirmed that your diversion was entirely successful. ‘not entirely sure what your Army and Navy types would say, but we can confirm that the diversion on the mainland has captured Leizhou and is already driving towards Zhanjiang. And our pilots report that that city is ablaze.”

“And what does that mean?” Wilson asked this is a calm, kindly voice.

“Conclusion? The Chinese rising has been entirely successful. And most of the Jap divisions are trapped on Hainan.”

“Having been tipped off about our assault there.” Wilson said as he considered this report. He turned to his own staff. “Is this confirmed?”

“Yes Sir,” his Chief of Staff replied.

“And what is your opinion on continuing the attack on Hainan?”

“Well Sir,” the Chief continued, “Fourth Division are nearly at Haikou; they were first in and overwhelmed the Jap defences before they had a time to organise themselves. The map shiows progress on day one and on day two. Twenty-third are still pushing forward; they’ve abandoned ‘D’ Beach and are relying on ‘C’ Beach, but they’ve defeated the Jap second line and are trying their best to come up to Fourth Division’s left flank...”

“..but?”

“I doubt that they can do it, Sir. That nice empty area where they could set up Corps HQ? It’s a bloody chain of marshlands and paddy fields. Every tree-line is a defensive point for the enemy. I don’t think that Fourth can count on the Twenty-third.”

“And the poor Forty-seventh I’ve seen,” Wilson said with resignation. “Any chance of re-positioning them to support the Twenty-third?”

“No Sir,” the injured Royal Navy officer mumbled. “It’ll take days to reorganise them.”

“Tell me, what are the conditions like for the men ashore?”

“Terrible,” the Chief of Staff replied. “Fourth Division will have to halt soon and Twenty-third are running out of ammunition and fresh water.”

“The enemy?”

The RAF officer nodded. “We can see that the Japanese have organised themselves defensively. Three divisions of infantry are moving up from ‘E’ Beach to threaten the Twenty-third. We’re trying our best to harry them but the Japanese air defences remain intact.”

“And,” the Chief of Staff, wanting to push the meeting along added, “Twenty-third are already very heavily engaged.”

“What about the other three divisions?”

The RAF officer grimaced. “Most of them are facing Fourth Division, though we have noticed a brigade moving here,” he jabbed at a chart for the gap between Fourth Division’s exposed left flank and the front of Twenty-third division.

Wilson closed his eyes. “When does General Brooke arrive?”

Another Royal Navy officer looked at his notes. “Tomorrow night, with the Army HQ and a few divisions. The Australians and the rest of the Army two days after that.”

Wilson was a brave man, and he knew that if he landed more men on Hainan he would reinforcing failure. The division on the mainland was achieving success, but would soon be horribly overwhelmed as the inevitable Japanese counter-attack developed.

“The Forty-seventh will land to support the Fifty-fifth, effective immediate. I want you to send a note to General Morgan at ‘C’ Beach. I’m calling off the landings on Hainan. Fourth Division to retire to ‘B’ Beach.” He turned to the Royal Navy contingent. “Can you get them off?”

They all nodded. Wilson closed his eyes. “I accept full responsibility for this of course,” he said quietly. “Could one of you get to the Fifty-fifth?”

The Chief of Staff nodded. “Message, Sir?”

“That Fourth Army is on the way. Tell them to keep pushing on, and that the Morgan’s Corps, followed by the Army, will reinforce them from tomorrow.”

The meeting concluded, Wilson returned ‘up top’ to view the burning coastline of Hainan. In the distance, the beach now to the South, Wilson looked at the burning port and the narrow entrance to the Ba Gate Wan waterway.

The decks were crowded with tired and injured infantrymen, men who relaxed with relief as Wilson waved away their attempts to rise to their feet or to salute him. In the distance, the plumes of smoke marking the position where Britain’s great ‘turning point’ had stalled and then failed terribly, lay an island, an island that Wilson hoped with a rare violence that he would never see again. The battle of Hainan was over.

[Game Effect] – Longbow, the diversion aside, is a bloody and tragic failure.

I’ve told you about the game – I landed the 3 INF divisions. Well, not a lot was going in the Far East at that point and I was busily taking screenies of the war in Russia. So when my 3 INF turned out to have engaged a dozen jap divisions you can see why the result was a setback, though the diversion on the Chinese mainland worked as there was virtually nothing to stop my 1 Mot division as it rumbled ashore. Simply put, when playing the game the Jap AI put everything in Southern China on Hainan and I was sloppy (this entire AAR is based on one of my early games of HOI2 DD) hence the disaster.

Yet another setback for the British led part of the war, and I feel that I must explain why (in AAR terms). The build-up to this, and the landings themselves, are based on British/Free French efforts against Dakar and Madagascar, both of which were badly planned and led. Both of those campaigns were marred by poor intelligence on the enemy forces, a total lack of secrecy amongst the planning officers, and a failure to take responsibility amongst senior officers. All of this is in evidence here: Morgan, the man with knowledge of the planning of this engagement, is ashore with his men, leaving the bewildered Wilson to arrive and try to save the landings. His decision, to concentrate on the mainland and allow Hainan to be blockaded, is probably the best decision of the entire operation and shows that whilst Wilson wasn’t a fantastic general, he was a competent, humane officer with the courage to make difficult choices. He reinforces success, not failure, and the remnants of V Corps are lucky to have Wilson at the tiller. They never had a great chance of victory, but with their few advantages squandered away, largely at the planning stages, the brave but doomed efforts of the British infantry are in vain. Expect questions to be asked of Pound (who was the senior advocate in the military for the landings) and the War Office.

If Hainan, both in the game and the story, has one strategic crumb to be gained, it is this: with 12 INF divisions now pinned on an island surrounded by the massed fleets of the Commonwealth, the efforts of Auchinleck in Burma/Yunnan and the armies pushing into Siam from Burma/Malaya now have a chance. For those interested, prior to completing this post I did a quick ‘no fog’ and Indochina is virtually empty.

Trekaddict: A prophetic comment, mon brave

Enewald: The Dieppe comparison is certainly an interesting one. At least RN dominance of the seas saves V Corps.

El Pip: Well, 4th and 23rd Divisions do adequately, but the Londoners of 47th are the first dominos to fall. The divisional landing points are widely separated, certainly more than in Normandy 1944, and so this inability to provide mutual support could be a vital factor.

Kurt_Steiner: We’re in ‘or else’ territory now!

Zhuge Liang: You are proved correct Sir!

DonnieBaseball: A bit like our hopes of overcoming the US in the World Cup, sadly not.

Sir Humphrey: An interesting comment, as essentially you are correct: capturing Hainan merely gives the Auk and his men a better chance. It was a bold plan but is now undone.

Last edited:

Well that was a disaster, let's hope that the right lessons can be learned from it. Hainan's now going to be very difficult to break open without very gamey tactics, I assume that it's going to by bypassed and left to rot although that would be a blow after the fanfare this operation was greeted with.

Is the landing on the mainland a serious one that can be reinforced quickly? Another foothold on the mainland's arguably a far more important prize than Hainan ever was. Also it looks like you've got a task ahead of you explaining the logic of the Japanese AI, I certainly don't envy you it.

Is the landing on the mainland a serious one that can be reinforced quickly? Another foothold on the mainland's arguably a far more important prize than Hainan ever was. Also it looks like you've got a task ahead of you explaining the logic of the Japanese AI, I certainly don't envy you it.

I could see Pound being the fall guy for this, especially factoring in his failing health, if this whole thing goes pear-shaped.

At least the diversionary attack went well--perhaps if V Corps can be redeployed in time to keep all those Japanese bottled up on Hainan, the rest of Brooke's army can head up the coast to relieve Hong Kong? Then just tell the press that the Hainan landings were in fact the diversion which succeeded and it all looks brilliant.

At least the diversionary attack went well--perhaps if V Corps can be redeployed in time to keep all those Japanese bottled up on Hainan, the rest of Brooke's army can head up the coast to relieve Hong Kong? Then just tell the press that the Hainan landings were in fact the diversion which succeeded and it all looks brilliant.

I suppose it depends how quickly recovery and reinforcement can arrive. Perhaps a 'relief' and then break out from Hong Kong is cooking in someone's head back @ HQ? Then again, Hong Kong perhaps does not hold in the same mind-set as Ladysmith nor even Mafeking?

After reading Haardrade's update -and bearing in mind my own experiences-, I begin to feel that we are all doomed in what concerns landings.

Well, many options are still there to be explored...

Well, many options are still there to be explored...

I must say I was expecting Longbow to go alot worse than that and the success of the mainland diversion goes along way to redeeming it. On it's own terms it was a failure certainly, but taking the wider view it wasn't a complete disaster.

If the bottleneck can be held then Longbow still meets it's objectives (Hainan is useless if blockaded) and there's a decent foothold on the mainland. As an added bonus there should be a shuffle up in high command, some good lessons learnt and we may even see Pound pushed out, all of which would be very good in the medium-long term.

If the bottleneck can be held then Longbow still meets it's objectives (Hainan is useless if blockaded) and there's a decent foothold on the mainland. As an added bonus there should be a shuffle up in high command, some good lessons learnt and we may even see Pound pushed out, all of which would be very good in the medium-long term.

Chapter 200 (bloody hell), near Nujiang, China, 20 May 1942

NOTE - I recommend that for the second part of this update the reader has a highland tune in the background. "Highland Cathedral" is my particular suggestion.

The Indians filed through the forest happily enough. Tough and well-trained, their General, Slim, had received alarming reports of a massive Japanese encroachment on British-held territory. The RAF, launching bombing raids deep into China, had, after two days of confusion, finally been tasked with identifying the nature of the threat. Hurricanes from Mandalay had flown low over the mountains, and of the dozen aircraft that returned seven had confirmed the news. Japanese, thousands of Japanese, were flooding through the valleys and up the mountains. Having lured Auchinleck's army into 'their' territory, the Japanese were now pouncing on the tired and disorganised British and Indian troops. Lieutenant General Sir Lewis 'Piggy' Heath, supposedly commanding this stretch of the line, had been silent: not one order had been issued from II Indian Corps Headquarters and most of his divisions, still reorganising, instinctively started to pull back. The other leader of a Corps in the area, Major-General (Acting Lieutenant General) Slim, was left stranded on the Northern-most point of the front. As Heath's Corps trudged miserably away back into Burma, Slim's III Indian Corps prepared to fight for its very existence and to deal with, to stall, the Japanese wherever they advanced. Starting with with the Japanese troops who threatened the critical junction between the two retreating Commonwealth Corps.

A single rifle platoon, supported by the new Mark II anti-tank rifles from various platoons, struck the Japanese lines first. The company CO waited at the tree-line with the rest of his company and watched as his men, keeping the pace neatly, fell upon the disorganised Japanese.

A few miles away as his men rested, Lieutenant Colonel Ian MacAlister Stewart, 13th Laird of Achnacone, sipped on a tin mug of 'gunfire', the very strong, very sweet tea that the Highland regiments were famous for. Stewart thanked his batman, Drummer Hardy, and stared at the report from the Indians from neighbouring II Indian Corps, realising that General Heath had pretty much abandoned not only his temporary command, 12th Indian Brigade, but much of the British, Indian and Nepalese troops. Whilst Heath fussed with his plans to disperse the troops, hoping to regroup in Burma, he had seemingly forgotten that only a thin line of men protected the retreating divisions, as well as the vital communications links that served this Northern sector of the front. Stewart whistled a passable "Scotland Forever" before turning to his one remaining staff officer.

"You, Lieutenant?"

"Carpenter Sir, Bombay Light Horse".

"Show me the direction of advance."

The two men, one acting as a brigade commander and the other acting as a staff officer, strolled to an upturned pile of ammunition crates that served as a makeshift table. Carpenter unfurled a rolled up map and pointed to a thin high ridge.

"Here Sir, a place called Dalongjing. From what our scouts said they'll break through our lines there."

"More than that, lad, they'll be in amongst our rear. We're the shield, and if we are pierced..."

"With only one passable road, and mile upon mile of stranded trucks?" The staff officer blanched.

Though, deep down, Stewart knew the answer to the question, he asked it anyway. "And what battalion covers that part of the line?"

"2nd Battalion Argyll and Sutherland, Sir."

"My lads eh." Stewart offered a sad sigh and closed his eyes.

"Shall I send a runner to them?"

"No lad, get to division as fast as you can. We need reinforcing, everything they can get."

"We, Sir?"

"Aye lad, we. I'm not going to order my men to stand and die whilst I sit here at headquarters waiting for an orderly to tell me what I need to know." He looked at the ridge, which shielded much of III Indian Corps from the approaching Japanese. "Every man who can carry a rifle, the cooks and clerk's an ‘all, give 'em a Lee Enfield." He thrust a finger at the ridge. "I want every man of the brigade supporting us." To emphasise this point, Stewart loaded his pistol, put on his battle bowler, and ran for the front. He skidded to a halt as it suddenly began raining. "Can you imagine retiring to Burma in this?" He waved a despairing hand at the heavens; his shirt was already drenched by the heavy rainfall. "That's all we need. Mon-bloody-soon isn't supposed to be until June."

It had stopped raining by the time Stewart reached the dug-in troops of his own battalion, the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. His battalion 2IC, Major Macdonald, was supervising the efforts of a pioneer section to clear a rough line of small trees and shrubs that lay a hundred yards from the battalion's main position and provided ideal cover for the still distant enemy.

"I thought you'd come back Sir," Macdonald greeted him as he saluted. He gestured to the sweating, muddy troops of the pioneer section. "We don't want this to offer cover for the enemy." Macdonald placed one hand in another, wringing his hands slightly in an intriguing gesture that Stewart had never seen before. "How many of them, Sir?"

The reference to 'them' was obvious. "At least a division," he said unhappily.

"And we're it?"

"Aye we are, until we are given the nod to fall back or we are reinforced by the rest of 'Division."

Macdonald went to speak but stopped himself and walked slowly over to where the rest of the battalion worked to make the thin line of trenches into a lethal killing zone. Stewart walked over to the far left of his position, where A Company's 8 Platoon guarded the exposed end of the position. Typically for 8 Platoon, they were cautiously cheerful. One of the officers, 2Lt Shiach, handed Stewart a photograph.

"Happier times, Sir."

"Where was that? Malaya?"

"Yes Sir, yes it was. Last year, before the move here," he waved towards the muddy ridge. "We'll be alright, though."

"You'll be alright," Stewart said as he returned to the centre of his line. Piper Herdsman, a short, slightly built teenager from a small village in Renfrewshire, started to beat his pipes into life.

"What would you like Sir?" Herdsman had a high-pitched, nervous voice, but a cheeky, almost cocky nature.

"Highland Cathedral lad, sound it loud and well across this blasted ridge". As Herdsman began the sad, steady tune Stewart looked into the faces of his men. They looked young, terribly young, and though there was the occasional glint of defiance there were also the wide-eyes of apprehension.

"Alright, lads, you know what you need to do. The Japs will be here soon, you know they don't surrender. Neither will you. We fight here, or we die." He finished his brutal delivery and thanked God that he had insisted on the battalion training for just this kind of holding action. Along the line the men, now augmented by seventy 'odds and sods' from the rest of the brigade, readied their weapons. Stewart waited patiently, realising that this was the first action he had fought since the end of the Great War. He noted, again, the strange silence before battle, then looked heavenward for signs of RAF or Japanese aircraft. But the gloomy skies were empty of man-made irritants; only the heavy clouds threatened Stewart's men.

"Here the bastards come," a voice brayed from one of the two rifle companies manning the line. The third, Stewart' weakest, waited with the 'odds and sods' to plug the gaps, but at best he had only four, perhaps five, scratch platoons with which to reinforce the Scotsmen manning the line. The machine guns, anti-tank rifles and mortars, had been distributed along the front in positions where, Stewart hoped, their fields of fire would create a killing ground. MacDonald and the Mortar Platoon had paced the ground and the two and three inch mortars had pre-determined target areas; for most of them this would be the line of foliage that had only just been partially cleared. Stewart looked at the line, a thin scattered group of men that looked very fragile in places, and which lacked the depth that the rulebook considered necessary for a protracted defence. In a concession to convention Stewart had a thin spread of 'outposts', focussed primarily on his exposed flanks, to give advance warning of the approaching Japanese. These rifle sections had orders from Major MacDonald to 'put up a good show' against the Japanese vanguard before retiring as best they could to the main line. And they were in action now, the sharp crack of the Lee Enfields firing into the trees silencing the chatter amongst the troops. A few ragged shouts in English signalled that the defence was a robust one, but the increasing yells in a tongue totally foreign to Stewart and most of his men reminded them that the enemy was strong. Stewart, standing in the best vantage point that he could find, a muddy rise next to a copse of trees, saw four Scotsmen burst from their outpost well in front of the main battalion in full flight.

"Covering fire! C'mon lads, wake up!" Half a dozen officers carried the message along the lines and as the first Japanese, using the cover of the tree line, targeted the British, the first grenades began to fall amongst the Argylls and Sutherlanders. The mortars opened fire in reply, killing a Japanese here and there but also falling harmlessly into empty ground.

The Japanese fell back, but only so far so they broke off from Stewart’s main line. They turned their fire on the scattered strongpoints of Stewarts ‘outposts’.

“Do we go forwards to help?” That was Lt Shiach.

“Aye lad, take your platoon and rush them. But come back.”

Shiach and his men advanced cautiously, using the thick undergrowth to creep forward to add their fire to that of the beleaguered first line. The Scotsmen had ran forward with their Lee Enfields, had dropped to make use of the cover and were pouring fire into the enemy waves.

A sweating corporal pulled away from Shiach’s advance. “Sir!”

“What is it laddie?”

“Mr Shiach, Sir,” the corporal paused to catch his breath. “Permission to retire Sir. The outpost are overrun, they’re retreating with us”.

Stewart looked out and saw that the corporal was right. Rather than sweeping the Japanese away, Shiach was now covering the retreat from his thin first line. His main line would now see action. Stewart allowed that the line would bend, would be deeply threatened, but with his extra manpower he would not allow it to break. Each company was deployed, as much as they could, in a ‘horseshoe’ shape, with platoons on either flank deployed further ahead than the third platoon, which was a standard ‘defence in depth’ pattern. This meant that the ‘main line’ was really like a two interacting lines, and though as it wasn’t a particularly ‘deep’ line Stewart was treating it as one: he had no choice but to.

Shiach and his men trudged back and Stewart placed them in his final line, little more than a well disposed reserve (indeed, he intended to weaken it where he could to reinforce the main line) made up of the brigade manpower. Shiach, a restless officer, immediately wandered over to a gentle rise, where the Vickers machine guns had been placed behind a hastily cleared killing ground. Stewart was there himself, having seen the need to steady the nerves of these vital troops.

“Alright boys, you know those stories your daddies told you about Mons, about Arras. When they’re in range, and I mean effective range, you cut them down. But let ‘em get to eight hundred yards,” Stewart pointed to a tuft of tall grass that was at about the right distance to form a useful marker. “Eight hundred yards. D’ye get me?”

They smiled back, slightly nervously. Stewart grimaced, and then found himself tensing as the Japanese crept forward, coming straight for them. He could see the machine gunners, clustered around the battalion’s issue of machine guns, itching to fire their weapons, to push away these Japanese before they could threaten the squatting Scotsmen. Stewart, through gritted teeth, found himself cursing.

“Steady lads, steady, I know they’re fashious, but let them get close, to feel your birr!” He said this knowing that his nerves were exaggerating his Scottish lilt.

A sudden series of screams snapped his attention to the front. Somehow, the Japanese had managed to get snipers on his left flank and had caught his men there by surprise. Stewart could guess what was coming next.

“You, Sergeant?”

“McIvor Sir, from the Depot.”

Grab a platoon of good bayonet lads from the reserves Sergeant, and meet me on the left. Go!”

The Japanese opened fire along the length of the line, but it must have been at long range as few men were even endangered. Stewart and McIvor, who had assembled a platoon of reassuringly strong-looking highlanders, now stalked the few hundred yards to the extreme left, where the foliage was thickest and the firing line the weakest. Most of the defenders were crouching to avoid the accurate sniper fire from concealed positions. As Stewart neared the flank the Japanese cheered, and in the distance he saw their attack burst out cover to overwhelm his men.

Pinned down by an irritating sniper fire, scared witless by the loss of their officers and NCOs, the young Scotsmen nevertheless held their ground as a wave of Japanese infantrymen erupted from the deceptively calm trees to charge their positions. The handful of officers not felled by snipers did their best, and a ragged though accurate fire slaughtered the first rank of Japanese. But every Japanese who fell another three ran forward, reaching the first positions and bayoneting the few Scotsmen who still stood.

“Platoon!” Stewart cried out to his bayonet men. “Charge!”

Against conventional wisdom, which suggested that he should disengage and weaken the Japanese with effective fire, his men roared and counterattacked the disorganised Japanese. Stewart himself fought with a Lee Enfield and bayonet; his pistol had jammed and he wanted his men to see him dealing at close quarters with this enemy that he viewed with contempt. Running down into one sunken area, formerly a position for four of his infantrymen, Stewart and another Scotsman roared as they charged down into the position, bayoneting the NCO and young conscript who hadn’t expected the Scottish counterattack. Stewart, a tall man, swatted away the NCO’s rifle and, ignoring a shouted challenge from ahead, plunged his bayonet into the man’s chest. As they recovered their positions some of the Scots ran forward to take the fight to the enemy positions. McIvor dragged more than one over-confident highlander back to their own lines.

One officer was left unwounded, a captain who had held his position with the thanks of one of the new Mark 2 Boy’s Anti-tank rifles; with an increased calibre and a reduced recoil it was a useful if unwieldy weapon but it had helped. After confirming that the captain would guard the left flank Stewart trudged to his HQ, where Heardsman still played his bagpipes.

Macdonald still lived, having repulsed an attack on the right flank similar to that on the left; the major looked dazed as fresh Japanese troops now crept forward along the centre of the line. Knowing what could easily be dealt with, Macdonald nodded to a nearby machine gun position; a short burst ended the Japanese creeping advance.

“They’re incessant,” Macdonald greeted Stewart. “We cannot hold on much longer.”

“Nightfall,” Stewart said softly. “We’ll hang ‘till nightfall and then retire down the slope.”

“Will the Army be out by then?”

Stewart said nothing, but made ready with his rifle as another wave of Japanese surged across the full front of the ridge.

“Give em trouble lads,” Stewart muttered, as along the line the rifles and machine guns opened fire. Stewart was yet again impressed by the power of a British battalion in defence as his men went about their business. Stewart realised that with this level of action the ammunition state, particularly of his more distant positions, was a looming threat.

“How many rounds do the lads have?” He asked this of one of the lightly wounded, a corporal who was now dragging crates of Lee Enfield rounds to the lines.

“An hour, then we’re out Sir.” He kept on with his task, stumbling through weakness. The Japanese attack had now become bogged down in the killing zone ahead of the Scottish positions. Small pockets of Japanese would occasionally charge forward only to be cut down by accurate (and heavy) British fire. Sometimes one of the Argylls would fall, either to a Japanese who managed to get into the British lines; but more and more of them were falling to lethal Japanese sniper fire.

This latest attack bloodily repulsed, Stewart walked to the rear of his line, to better view the retreat of Slim and Heath’s troops. Far below him, he could see the long thin lines of the British and Indian battalions as they walked dejectedly back towards British Burma. With gritted teeth, Stewart realised that he and his men would have to hold this ridge for a little while longer.

He looked at the Japanese. There must have been thousands of them and with artillery support they meant to prevail.

“Right lads, this is it, break this bastard attack and you can be sure that they’ll not try again. Steady lads!”

The final attack broke out of the dense trees on the left flank; the Japanese seemed to sense Stewart’s concerns that it was his weakest position and threw hundreds of men at it in a determined attempt to roll up the thin British line. Trusting that his men would cope as best they could with this assault, Stewart remained firmly in his battalion HQ, dealing with requests for reinforcement with one simple ‘no’ and trying to maintain ‘grip’ on the battle. But as more and more platoons begged for ammunition, as the left flank was finally overcome, and as there was nothing between the victorious Japanese and the long, vulnerable lines of retreating men, Stewart grabbed his rifle and launched a final, maddening charge. Pushing past his own men, as well as the Japanese, Stewart spotted a fat Japanese senior officer, dressed simply in a crisp white shirt and dark green trousers and riding boots, calmly slicing into his men with a samurai sword.

“Leave him! That fat bastard is mine!”

The Japanese officer spotted the British Colonel running towards him and patiently positioned himself with his sword ready to sweep down on the Scotsman. Stewart roared a challenge and raised his rifle so as to block his opponent’s sweeping move. The Japanese officer made a quarter turn to the right, as if to allow Stewart to run past him. Stewart stumbled to a halt to trip on the thick undergrowth as his enemy raised his sword above his head, looking very formal and very determined. There was only one thing to do; feigning concussion Stewart made little movement, and as his enemy took his time to perfect the killing blow Stewart, quickly, kicked the officer squarely in the testicles. Falling back, tears of shame and pain in his eyes, the Japanese officer was finished off by half a dozen of the vengeful Scotsmen.

And suddenly there were Englishmen, hordes of bloody Englishmen. As one company after another marched up the track towards the Scotsmen an English officer casually approached Stewart.

“My name’s Wills, CO 4th Somerset Light Infantry.”

Stewart shook his hand. “Stewart, Lieutenant Colonel Stewart. What are you doing here?”

“General Slim’s compliments, Sir, and we’re to cover your withdrawal. You did it Stewart.” Lieutenant Colonel Wills, sensing Stewart’s confusion, spoke softly. “You won, Colonel, it’s over.” Wills was covered in sweat and Stewart realised that the retreat must have been arduous in such hot weather. Though given the preference, Stewart would have taken that over defending this Godforsaken ridge any day. As Wills listened to Macdonald and the other officers as they described the position, Stewart’s attention was distracted to where a small litter of highlanders carried Heardsman to the medics. His chest was a mess of blood as his hands clenched the bagpipes that he played throughout the short battle. Next to him Lieutenant Shiach was carried by two of his men, blood seeping from the mortal wound to his groin. Shiach himself had long since fainted, and he hung limp and pale as the two sturdy highlanders carried him home. The Argyll and Sutherlanders were utterly exhausted, but they had held their ground. The Army was safe.

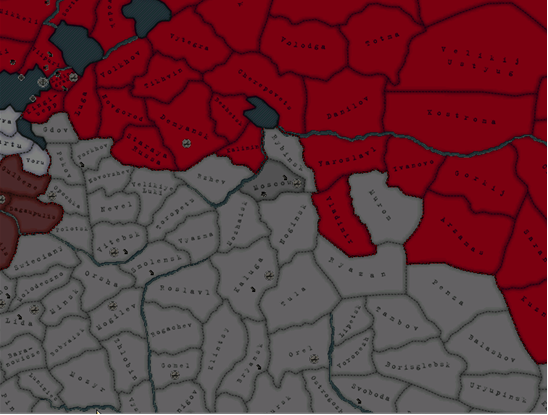

[Game Effect] – Another ‘small scale’ action as a battalion of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders repulses a Japanese attempt to harry the retreat of the left flank of the Commonwealth Army.

In game terms it was a sadly familiar tale; the British were low on Org and were easily pushed out by the Japanese. But that wouldn’t have made a good story and so I focussed on the actual retreat itself, with perhaps a nod to ‘Zulu’ and the Sharpe stories a heroic rearguard action is fought.

Colonel Stewart was real, he has a wiki entry but I read about him in one of my WW2 books and loved the idea of him featuring in KFM. Unlike my usual battalion CO, the fictional Colonel Belsay, Stewart was practically married to the regiment and spurned the necessary courses and jobs that would have taken him to higher rank; all this done to keep him with his battalion. A true hero, he and his men have saved the Army.

And so the inevitable Japanese counterattack is launched, sending Heath and Slim scurrying from the left of Auchinleck’s position. Coming at the same time as the failure of Operation Longbow, the next update will see how Halifax is coping with this increasingly bad news.

Zhuge Liang: I am indeed fighting two opponents here – the Japanese, and the bloody AI!

DonnieBaseball: I think that the redeployment of V Corps is certainly possible – the key question is the condition they’re in after they get there. But it’s probably the best plan to take things forward.

Sir Humphrey: All will be revealed in the next update...

Enewald: Dumb indeed!

Kurt_Steiner: I know what you mean, and certainly Hainan was bloody awful.

El Pip: I really have conditioned you haven’t I?! Eighteen months of this gloom and we view this as ‘not bad’. You are right of course, and much can still be gained as a result of Longbow.

Nathan Madien: Yes, I can just see the ‘Timewatch’ special, or the Richard Holmes three part series on the Pacific War.

NOTE - I recommend that for the second part of this update the reader has a highland tune in the background. "Highland Cathedral" is my particular suggestion.

The Indians filed through the forest happily enough. Tough and well-trained, their General, Slim, had received alarming reports of a massive Japanese encroachment on British-held territory. The RAF, launching bombing raids deep into China, had, after two days of confusion, finally been tasked with identifying the nature of the threat. Hurricanes from Mandalay had flown low over the mountains, and of the dozen aircraft that returned seven had confirmed the news. Japanese, thousands of Japanese, were flooding through the valleys and up the mountains. Having lured Auchinleck's army into 'their' territory, the Japanese were now pouncing on the tired and disorganised British and Indian troops. Lieutenant General Sir Lewis 'Piggy' Heath, supposedly commanding this stretch of the line, had been silent: not one order had been issued from II Indian Corps Headquarters and most of his divisions, still reorganising, instinctively started to pull back. The other leader of a Corps in the area, Major-General (Acting Lieutenant General) Slim, was left stranded on the Northern-most point of the front. As Heath's Corps trudged miserably away back into Burma, Slim's III Indian Corps prepared to fight for its very existence and to deal with, to stall, the Japanese wherever they advanced. Starting with with the Japanese troops who threatened the critical junction between the two retreating Commonwealth Corps.

A single rifle platoon, supported by the new Mark II anti-tank rifles from various platoons, struck the Japanese lines first. The company CO waited at the tree-line with the rest of his company and watched as his men, keeping the pace neatly, fell upon the disorganised Japanese.

A few miles away as his men rested, Lieutenant Colonel Ian MacAlister Stewart, 13th Laird of Achnacone, sipped on a tin mug of 'gunfire', the very strong, very sweet tea that the Highland regiments were famous for. Stewart thanked his batman, Drummer Hardy, and stared at the report from the Indians from neighbouring II Indian Corps, realising that General Heath had pretty much abandoned not only his temporary command, 12th Indian Brigade, but much of the British, Indian and Nepalese troops. Whilst Heath fussed with his plans to disperse the troops, hoping to regroup in Burma, he had seemingly forgotten that only a thin line of men protected the retreating divisions, as well as the vital communications links that served this Northern sector of the front. Stewart whistled a passable "Scotland Forever" before turning to his one remaining staff officer.

"You, Lieutenant?"

"Carpenter Sir, Bombay Light Horse".

"Show me the direction of advance."

The two men, one acting as a brigade commander and the other acting as a staff officer, strolled to an upturned pile of ammunition crates that served as a makeshift table. Carpenter unfurled a rolled up map and pointed to a thin high ridge.

"Here Sir, a place called Dalongjing. From what our scouts said they'll break through our lines there."

"More than that, lad, they'll be in amongst our rear. We're the shield, and if we are pierced..."

"With only one passable road, and mile upon mile of stranded trucks?" The staff officer blanched.

Though, deep down, Stewart knew the answer to the question, he asked it anyway. "And what battalion covers that part of the line?"

"2nd Battalion Argyll and Sutherland, Sir."

"My lads eh." Stewart offered a sad sigh and closed his eyes.

"Shall I send a runner to them?"

"No lad, get to division as fast as you can. We need reinforcing, everything they can get."

"We, Sir?"

"Aye lad, we. I'm not going to order my men to stand and die whilst I sit here at headquarters waiting for an orderly to tell me what I need to know." He looked at the ridge, which shielded much of III Indian Corps from the approaching Japanese. "Every man who can carry a rifle, the cooks and clerk's an ‘all, give 'em a Lee Enfield." He thrust a finger at the ridge. "I want every man of the brigade supporting us." To emphasise this point, Stewart loaded his pistol, put on his battle bowler, and ran for the front. He skidded to a halt as it suddenly began raining. "Can you imagine retiring to Burma in this?" He waved a despairing hand at the heavens; his shirt was already drenched by the heavy rainfall. "That's all we need. Mon-bloody-soon isn't supposed to be until June."

It had stopped raining by the time Stewart reached the dug-in troops of his own battalion, the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. His battalion 2IC, Major Macdonald, was supervising the efforts of a pioneer section to clear a rough line of small trees and shrubs that lay a hundred yards from the battalion's main position and provided ideal cover for the still distant enemy.

"I thought you'd come back Sir," Macdonald greeted him as he saluted. He gestured to the sweating, muddy troops of the pioneer section. "We don't want this to offer cover for the enemy." Macdonald placed one hand in another, wringing his hands slightly in an intriguing gesture that Stewart had never seen before. "How many of them, Sir?"

The reference to 'them' was obvious. "At least a division," he said unhappily.

"And we're it?"

"Aye we are, until we are given the nod to fall back or we are reinforced by the rest of 'Division."

Macdonald went to speak but stopped himself and walked slowly over to where the rest of the battalion worked to make the thin line of trenches into a lethal killing zone. Stewart walked over to the far left of his position, where A Company's 8 Platoon guarded the exposed end of the position. Typically for 8 Platoon, they were cautiously cheerful. One of the officers, 2Lt Shiach, handed Stewart a photograph.

"Happier times, Sir."

"Where was that? Malaya?"

"Yes Sir, yes it was. Last year, before the move here," he waved towards the muddy ridge. "We'll be alright, though."

"You'll be alright," Stewart said as he returned to the centre of his line. Piper Herdsman, a short, slightly built teenager from a small village in Renfrewshire, started to beat his pipes into life.

"What would you like Sir?" Herdsman had a high-pitched, nervous voice, but a cheeky, almost cocky nature.

"Highland Cathedral lad, sound it loud and well across this blasted ridge". As Herdsman began the sad, steady tune Stewart looked into the faces of his men. They looked young, terribly young, and though there was the occasional glint of defiance there were also the wide-eyes of apprehension.

"Alright, lads, you know what you need to do. The Japs will be here soon, you know they don't surrender. Neither will you. We fight here, or we die." He finished his brutal delivery and thanked God that he had insisted on the battalion training for just this kind of holding action. Along the line the men, now augmented by seventy 'odds and sods' from the rest of the brigade, readied their weapons. Stewart waited patiently, realising that this was the first action he had fought since the end of the Great War. He noted, again, the strange silence before battle, then looked heavenward for signs of RAF or Japanese aircraft. But the gloomy skies were empty of man-made irritants; only the heavy clouds threatened Stewart's men.

"Here the bastards come," a voice brayed from one of the two rifle companies manning the line. The third, Stewart' weakest, waited with the 'odds and sods' to plug the gaps, but at best he had only four, perhaps five, scratch platoons with which to reinforce the Scotsmen manning the line. The machine guns, anti-tank rifles and mortars, had been distributed along the front in positions where, Stewart hoped, their fields of fire would create a killing ground. MacDonald and the Mortar Platoon had paced the ground and the two and three inch mortars had pre-determined target areas; for most of them this would be the line of foliage that had only just been partially cleared. Stewart looked at the line, a thin scattered group of men that looked very fragile in places, and which lacked the depth that the rulebook considered necessary for a protracted defence. In a concession to convention Stewart had a thin spread of 'outposts', focussed primarily on his exposed flanks, to give advance warning of the approaching Japanese. These rifle sections had orders from Major MacDonald to 'put up a good show' against the Japanese vanguard before retiring as best they could to the main line. And they were in action now, the sharp crack of the Lee Enfields firing into the trees silencing the chatter amongst the troops. A few ragged shouts in English signalled that the defence was a robust one, but the increasing yells in a tongue totally foreign to Stewart and most of his men reminded them that the enemy was strong. Stewart, standing in the best vantage point that he could find, a muddy rise next to a copse of trees, saw four Scotsmen burst from their outpost well in front of the main battalion in full flight.

"Covering fire! C'mon lads, wake up!" Half a dozen officers carried the message along the lines and as the first Japanese, using the cover of the tree line, targeted the British, the first grenades began to fall amongst the Argylls and Sutherlanders. The mortars opened fire in reply, killing a Japanese here and there but also falling harmlessly into empty ground.

The Japanese fell back, but only so far so they broke off from Stewart’s main line. They turned their fire on the scattered strongpoints of Stewarts ‘outposts’.

“Do we go forwards to help?” That was Lt Shiach.

“Aye lad, take your platoon and rush them. But come back.”

Shiach and his men advanced cautiously, using the thick undergrowth to creep forward to add their fire to that of the beleaguered first line. The Scotsmen had ran forward with their Lee Enfields, had dropped to make use of the cover and were pouring fire into the enemy waves.

A sweating corporal pulled away from Shiach’s advance. “Sir!”

“What is it laddie?”

“Mr Shiach, Sir,” the corporal paused to catch his breath. “Permission to retire Sir. The outpost are overrun, they’re retreating with us”.

Stewart looked out and saw that the corporal was right. Rather than sweeping the Japanese away, Shiach was now covering the retreat from his thin first line. His main line would now see action. Stewart allowed that the line would bend, would be deeply threatened, but with his extra manpower he would not allow it to break. Each company was deployed, as much as they could, in a ‘horseshoe’ shape, with platoons on either flank deployed further ahead than the third platoon, which was a standard ‘defence in depth’ pattern. This meant that the ‘main line’ was really like a two interacting lines, and though as it wasn’t a particularly ‘deep’ line Stewart was treating it as one: he had no choice but to.

Shiach and his men trudged back and Stewart placed them in his final line, little more than a well disposed reserve (indeed, he intended to weaken it where he could to reinforce the main line) made up of the brigade manpower. Shiach, a restless officer, immediately wandered over to a gentle rise, where the Vickers machine guns had been placed behind a hastily cleared killing ground. Stewart was there himself, having seen the need to steady the nerves of these vital troops.

“Alright boys, you know those stories your daddies told you about Mons, about Arras. When they’re in range, and I mean effective range, you cut them down. But let ‘em get to eight hundred yards,” Stewart pointed to a tuft of tall grass that was at about the right distance to form a useful marker. “Eight hundred yards. D’ye get me?”

They smiled back, slightly nervously. Stewart grimaced, and then found himself tensing as the Japanese crept forward, coming straight for them. He could see the machine gunners, clustered around the battalion’s issue of machine guns, itching to fire their weapons, to push away these Japanese before they could threaten the squatting Scotsmen. Stewart, through gritted teeth, found himself cursing.

“Steady lads, steady, I know they’re fashious, but let them get close, to feel your birr!” He said this knowing that his nerves were exaggerating his Scottish lilt.

A sudden series of screams snapped his attention to the front. Somehow, the Japanese had managed to get snipers on his left flank and had caught his men there by surprise. Stewart could guess what was coming next.

“You, Sergeant?”

“McIvor Sir, from the Depot.”

Grab a platoon of good bayonet lads from the reserves Sergeant, and meet me on the left. Go!”

The Japanese opened fire along the length of the line, but it must have been at long range as few men were even endangered. Stewart and McIvor, who had assembled a platoon of reassuringly strong-looking highlanders, now stalked the few hundred yards to the extreme left, where the foliage was thickest and the firing line the weakest. Most of the defenders were crouching to avoid the accurate sniper fire from concealed positions. As Stewart neared the flank the Japanese cheered, and in the distance he saw their attack burst out cover to overwhelm his men.

Pinned down by an irritating sniper fire, scared witless by the loss of their officers and NCOs, the young Scotsmen nevertheless held their ground as a wave of Japanese infantrymen erupted from the deceptively calm trees to charge their positions. The handful of officers not felled by snipers did their best, and a ragged though accurate fire slaughtered the first rank of Japanese. But every Japanese who fell another three ran forward, reaching the first positions and bayoneting the few Scotsmen who still stood.

“Platoon!” Stewart cried out to his bayonet men. “Charge!”

Against conventional wisdom, which suggested that he should disengage and weaken the Japanese with effective fire, his men roared and counterattacked the disorganised Japanese. Stewart himself fought with a Lee Enfield and bayonet; his pistol had jammed and he wanted his men to see him dealing at close quarters with this enemy that he viewed with contempt. Running down into one sunken area, formerly a position for four of his infantrymen, Stewart and another Scotsman roared as they charged down into the position, bayoneting the NCO and young conscript who hadn’t expected the Scottish counterattack. Stewart, a tall man, swatted away the NCO’s rifle and, ignoring a shouted challenge from ahead, plunged his bayonet into the man’s chest. As they recovered their positions some of the Scots ran forward to take the fight to the enemy positions. McIvor dragged more than one over-confident highlander back to their own lines.

One officer was left unwounded, a captain who had held his position with the thanks of one of the new Mark 2 Boy’s Anti-tank rifles; with an increased calibre and a reduced recoil it was a useful if unwieldy weapon but it had helped. After confirming that the captain would guard the left flank Stewart trudged to his HQ, where Heardsman still played his bagpipes.

Macdonald still lived, having repulsed an attack on the right flank similar to that on the left; the major looked dazed as fresh Japanese troops now crept forward along the centre of the line. Knowing what could easily be dealt with, Macdonald nodded to a nearby machine gun position; a short burst ended the Japanese creeping advance.

“They’re incessant,” Macdonald greeted Stewart. “We cannot hold on much longer.”

“Nightfall,” Stewart said softly. “We’ll hang ‘till nightfall and then retire down the slope.”

“Will the Army be out by then?”

Stewart said nothing, but made ready with his rifle as another wave of Japanese surged across the full front of the ridge.

“Give em trouble lads,” Stewart muttered, as along the line the rifles and machine guns opened fire. Stewart was yet again impressed by the power of a British battalion in defence as his men went about their business. Stewart realised that with this level of action the ammunition state, particularly of his more distant positions, was a looming threat.

“How many rounds do the lads have?” He asked this of one of the lightly wounded, a corporal who was now dragging crates of Lee Enfield rounds to the lines.

“An hour, then we’re out Sir.” He kept on with his task, stumbling through weakness. The Japanese attack had now become bogged down in the killing zone ahead of the Scottish positions. Small pockets of Japanese would occasionally charge forward only to be cut down by accurate (and heavy) British fire. Sometimes one of the Argylls would fall, either to a Japanese who managed to get into the British lines; but more and more of them were falling to lethal Japanese sniper fire.

This latest attack bloodily repulsed, Stewart walked to the rear of his line, to better view the retreat of Slim and Heath’s troops. Far below him, he could see the long thin lines of the British and Indian battalions as they walked dejectedly back towards British Burma. With gritted teeth, Stewart realised that he and his men would have to hold this ridge for a little while longer.

He looked at the Japanese. There must have been thousands of them and with artillery support they meant to prevail.

“Right lads, this is it, break this bastard attack and you can be sure that they’ll not try again. Steady lads!”

The final attack broke out of the dense trees on the left flank; the Japanese seemed to sense Stewart’s concerns that it was his weakest position and threw hundreds of men at it in a determined attempt to roll up the thin British line. Trusting that his men would cope as best they could with this assault, Stewart remained firmly in his battalion HQ, dealing with requests for reinforcement with one simple ‘no’ and trying to maintain ‘grip’ on the battle. But as more and more platoons begged for ammunition, as the left flank was finally overcome, and as there was nothing between the victorious Japanese and the long, vulnerable lines of retreating men, Stewart grabbed his rifle and launched a final, maddening charge. Pushing past his own men, as well as the Japanese, Stewart spotted a fat Japanese senior officer, dressed simply in a crisp white shirt and dark green trousers and riding boots, calmly slicing into his men with a samurai sword.

“Leave him! That fat bastard is mine!”

The Japanese officer spotted the British Colonel running towards him and patiently positioned himself with his sword ready to sweep down on the Scotsman. Stewart roared a challenge and raised his rifle so as to block his opponent’s sweeping move. The Japanese officer made a quarter turn to the right, as if to allow Stewart to run past him. Stewart stumbled to a halt to trip on the thick undergrowth as his enemy raised his sword above his head, looking very formal and very determined. There was only one thing to do; feigning concussion Stewart made little movement, and as his enemy took his time to perfect the killing blow Stewart, quickly, kicked the officer squarely in the testicles. Falling back, tears of shame and pain in his eyes, the Japanese officer was finished off by half a dozen of the vengeful Scotsmen.

And suddenly there were Englishmen, hordes of bloody Englishmen. As one company after another marched up the track towards the Scotsmen an English officer casually approached Stewart.

“My name’s Wills, CO 4th Somerset Light Infantry.”

Stewart shook his hand. “Stewart, Lieutenant Colonel Stewart. What are you doing here?”

“General Slim’s compliments, Sir, and we’re to cover your withdrawal. You did it Stewart.” Lieutenant Colonel Wills, sensing Stewart’s confusion, spoke softly. “You won, Colonel, it’s over.” Wills was covered in sweat and Stewart realised that the retreat must have been arduous in such hot weather. Though given the preference, Stewart would have taken that over defending this Godforsaken ridge any day. As Wills listened to Macdonald and the other officers as they described the position, Stewart’s attention was distracted to where a small litter of highlanders carried Heardsman to the medics. His chest was a mess of blood as his hands clenched the bagpipes that he played throughout the short battle. Next to him Lieutenant Shiach was carried by two of his men, blood seeping from the mortal wound to his groin. Shiach himself had long since fainted, and he hung limp and pale as the two sturdy highlanders carried him home. The Argyll and Sutherlanders were utterly exhausted, but they had held their ground. The Army was safe.

[Game Effect] – Another ‘small scale’ action as a battalion of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders repulses a Japanese attempt to harry the retreat of the left flank of the Commonwealth Army.

In game terms it was a sadly familiar tale; the British were low on Org and were easily pushed out by the Japanese. But that wouldn’t have made a good story and so I focussed on the actual retreat itself, with perhaps a nod to ‘Zulu’ and the Sharpe stories a heroic rearguard action is fought.

Colonel Stewart was real, he has a wiki entry but I read about him in one of my WW2 books and loved the idea of him featuring in KFM. Unlike my usual battalion CO, the fictional Colonel Belsay, Stewart was practically married to the regiment and spurned the necessary courses and jobs that would have taken him to higher rank; all this done to keep him with his battalion. A true hero, he and his men have saved the Army.

And so the inevitable Japanese counterattack is launched, sending Heath and Slim scurrying from the left of Auchinleck’s position. Coming at the same time as the failure of Operation Longbow, the next update will see how Halifax is coping with this increasingly bad news.

Zhuge Liang: I am indeed fighting two opponents here – the Japanese, and the bloody AI!

DonnieBaseball: I think that the redeployment of V Corps is certainly possible – the key question is the condition they’re in after they get there. But it’s probably the best plan to take things forward.

Sir Humphrey: All will be revealed in the next update...

Enewald: Dumb indeed!

Kurt_Steiner: I know what you mean, and certainly Hainan was bloody awful.

El Pip: I really have conditioned you haven’t I?! Eighteen months of this gloom and we view this as ‘not bad’. You are right of course, and much can still be gained as a result of Longbow.

Nathan Madien: Yes, I can just see the ‘Timewatch’ special, or the Richard Holmes three part series on the Pacific War.

I suppose resignation and then retiring to the drawing room with bottle of whisky and a revolver is too much to hope for?[Coming at the same time as the failure of Operation Longbow, the next update will see how Halifax is coping with this increasingly bad news.

Another excellent combat update and nice to see the Highlanders continuing to be hard as nails, though I do hope there is a plan in hand to replace those Boyes rifles!

200 chapters covering two years. If this trend continues, we will be in May 1944 by chapter 400.

By the way, exactly what is the 13th Laird of Achnacone?

By the way, exactly what is the 13th Laird of Achnacone?

Well, we run out of luck this time.

If the Japanese Army were knocking at No 10, it would be the case for that. But not now.

To avoid going to the funeral of the coolest guy with a rifle.

I suppose resignation and then retiring to the drawing room with bottle of whisky and a revolver is too much to hope for?

If the Japanese Army were knocking at No 10, it would be the case for that. But not now.

Why does the cool guy with a katana always die?

To avoid going to the funeral of the coolest guy with a rifle.

A thrilling update all round, it was nice to see the Japanese officer get a just punishment for being so bloody stupid in the middle of a battlefield.

If the Japanese Army were knocking at No 10, it would be the case for that. But not now.

Fortunately for Halifax, the Japanese Army he is facing isn't controlled by Remble.

Fortunately for Halifax, the Japanese Army he is facing isn't controlled by Remble.

Nor Germany is under Remble's, Kami88's or DVD-IT's control...

Chapter 201, Downing Street, 24 May 1942

Halifax assumed an air of nonchalance as his Cabinet gathered for their weekly meeting. He had barely slept over the last week, and was plagued by headaches and loss of appetite. More worrying, and something so far kept hidden from Lady Halifax, he had noticed that his bad hand, his left, was tingling. He had resolved to appoint a personal doctor, something that Templewood and Butler had been urging him to do for years anyway. Noting to himself that his recent loss of weight meant that yet another suit required ‘taking in’ he sighed and headed to the Cabinet Room.

“Good morning, Prime Minister,” the politicians muttered as he entered. After waving them back to their seats, Halifax took his own, and as he did he noticed that his left arm was twitching again. Out of the corner of his eye he saw Eden watching with interest.

“Erm, good morning,” Halifax said slowly. He waited whilst Cole poured him a cup of tea, the silence in the room a heavy one. Somewhere in the house a grandfather clock chimed ten o’clock. Cole, with studied calm, retired as Halifax looked around at his Cabinet. They look, Halifax thought, terribly disheartened. Do they know that I have no grand eloquence to offer?

“Shall we take the steepest fence first?” Only Butler smiled at the gloomy jest. “What of Opewation Longbow?”

As had been agreed, Eden spoke for the service ministers. “Fifth Corps has now landed on the Chinese mainland to reinforce the original diversionary attack. The city of Leizhou is now held by our troops and the Chinese guerrillas,” Eden said with certainty. “Fifty-fifth division has been relieved by the troops from Hainan and will soon push North, to capture Zhanjiang. The Chinese are working with General Wilson and will stage a major rising in the city to hinder Japanese resistance.

Halifax was taking notes; he was due to give a statement to the House of Lords later that day. “And what of the troops who landed on Hainan?”

“Well, Prime Minister,” Eden said carefully, we are looking at casualties of around twelve thousand men. Most of these were in the Forty-seventh division, who never really got off their beach. There are large numbers of missing,” Eden said quietly. “At present we are working with the Chinese to smuggle any trapped soldiers out.”

“A vainglowious effort,” Halifax said gloomily. “I am not sure that we should continue the thrust along the Chinese mainland.” He said this bleakly, looking drained.

“My Lord, we have to,” Eden barked in immediate response. “If we do not, then this Government is done for.”

“And,” Hankey now spoke, after offering a sharp look of rebuke to Eden, “the Navy managed to successfully stage one evacuation, from Hainan. I am not confident that we could as successfully evacuate Leizhou.”

“But you have sevewal squadwons there!”

Hankey smiled condescendingly. “Most of those, Prime Minister, are blockading Hainan and are guarding our supply convoys to the troops ashore.” He looked quickly at his notes. “And we are also pumping supplies to the Chinese into the area.”

“Wonald?”

Ronald Cross, the Secretary of State for Air, looked with sad eyes at both Eden and Halifax, sensing the tensions, the disagreements. “I agree with Anthony and Maurice,” he said softly.

Halifax sat back and looked at Stanley. “Oliver?”

“Agreed, Prime Minister, and I should add that confidence in our capacity to wage war has been severely dented. We’re seeing a trail off in currency dealing, and some of our neutral holders of sterling are starting to panic sell. They fear that the Government may fall.”

“And with this Japanese counterattack on the Burma fwontier,” Halifax’s voiced trailed off. “Let us be fwank. Appwise me, one of you. How catastwophic is this?”

For Halifax to be so blunt was surprising, and Templewood, so often the mediator in their meetings, drew attention to himself by a tactful cough. “Prime Minister, though I lack Anthony or Oliver’s understanding of public opinion, it has to be admitted that the failure to capture Hainan was significant setback for our war effort.”

Maxwell-Fyfe, the Home Secretary who so rarely spoke during discussions of the war, was nodding. “I doubt that there’s any risk of demonstration or disturbance here at home,” he said with confidence.

Halifax looked at his Home Secretary with disbelief. “But in the House?”

“Attlee is in trouble,” Butler said with a comradely chuckle. “Having supported the war, his last statement to the House was just as bellicose as ours. There’s little he can do, other than attack us for getting the Hainan thing wrong.” Butler looked at Eden, as if to reinforce that it was Eden who would shoulder the blame in the Commons.

It was now that Monckton, the newly created Minister without Portfolio, spoke up from the far end of the table. “My Lord, I have spoken with Lord Beaverbrook.”

“And?” Butler, unlike Eden and Hankey, didn’t know what was coming.

“Well, simply, Foreign Secretary, we tell the public that the attack of Five Corps on Hainan was a massive diversion to conceal our true objective, the landings on the Chinese mainland.”

“Will it work?” Butler was not convinced.

“Of course it will bloody well work,” Cuthbert Headlam, Minister of Transport, said angrily. “They’ll read it in his bloody papers and determine that we’ve been very clever.”

“Wab, will the Amewicans accept this version?”

“Er” Butler was caught unawares. “I don’t know. They were shown our plans from the off, so...”

“...so we tell them that we are blockading Hainan whilst pushing to help the Chinese on the mainland,” Eden finished, with a hint of exasperation. “My Lord, all of this points to our having to go on, on the mainland.”

Butler, annoyed at Eden’s interruption, jumped in to silence his opponent. “Roosevelt is whining on about sending American troops and supplies to China. This could show them that they don’t have to. It would also give us increased leverage in the Chinese Government.”

Halifax nodded sadly. “Alwight then, I think that we go wound the woom. Is evewyone agweed on pwessing ahead with the offensive on Lei...ah, the Chinese mainland?”

They all nodded, though Ronald Cross looked far from happy, and Templewood noticed this. “Something to add, Ronald?”

Cross, who had earlier seemed to agree to the attack, now looked unhappily at the de facto Deputy Prime Minister. “It’s just that...”

“...yes, Ronald. It’s just what?”

Cross smiled weakly at this gentle encouragement. “We’ve set the RAF up in Malaya and Burma. I’ve got dozens of new squadrons out there. And now you’ll ask for new planes for Leizhou...”

“The Army and the Navy has the same problem, Ronald,” Hankey said softly.

“I’m rather afraid you don’t. It’s not just the aircraft, it’s the airfields and the men to defend them. I’ve thrown aircraft at Burma and Hong Kong, and now Malaya, I’m not sure I can continually afford this dilution of our strength.”

Halifax looked with concern at his Air Minister. “But how bad is the air campaign?”

“Slessor’s doing his best over Siam and Burma, but the Japs are pouring in aircraft and are harassing our bombing efforts against their ground troops.” Cross looked tired, dispirited. Eden and Hankey exchanged concerned looks.