Basilieus Ioannes II, 1241-1268 (Part Three)

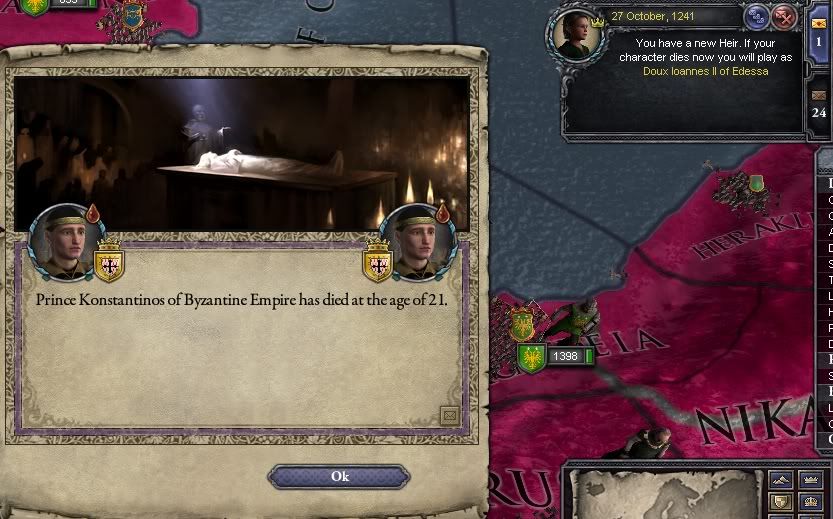

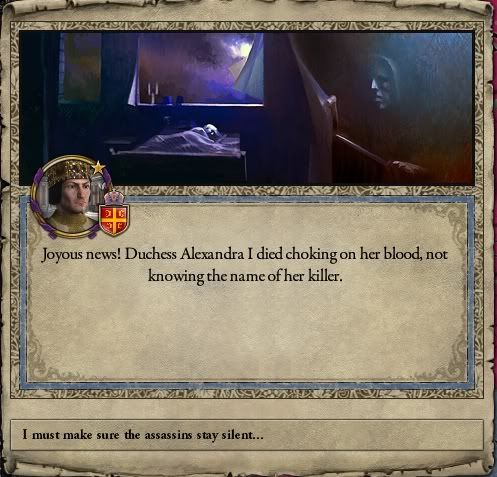

Ioannes had little time to grieve. The Emperor reacted quickly, sending assassins to kill the mother of his grandchild to ensure her lands passed to her son (and to prevent her from remarrying, and breeding half-brothers with troublesome claims). The Duchess was a kindhearted woman, but Ioannes had heard far too many tales from his grandfather of ‘kindhearted nobles’ who suddenly grew hearts of iron at the most inopportune time. Alexandra had far too much control over the boy who would inherit an Empire—kindly disposition or no, she had to go. When the Emperor heard a tale of his second son, the new Duke of Pest, cackling at his brother’s murder, more assassins left Constantinople. Duke Daniel did not live to see the next fortnight—such was the vengeance of a father shamed and hurt.

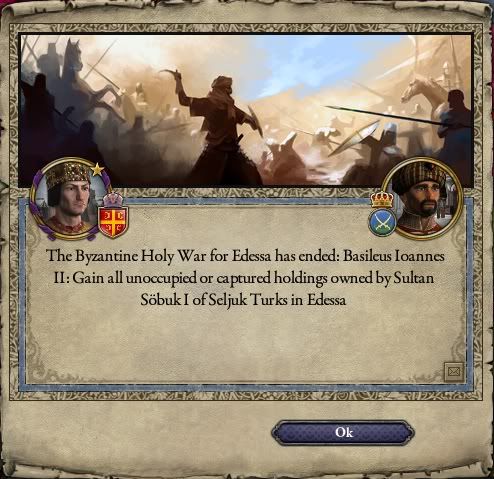

Meanwhile the Emir of the Sinai broke free from the Fatimid Caliphs once more, and Ioannes focused his rage into a swift campaign to take Jerusalem. Unlike last time, the Emperor actually reached the walls of the Holy City, the first Christian ruler to do so since the days of Heraklios. For eight months Ioannes put the place under siege with fire and works, only to have the Emir once again sign a peace with the Caliph that invalidated his war. Empty handed, the Emperor and his army marched home, their anger hot at being snubbed yet again.

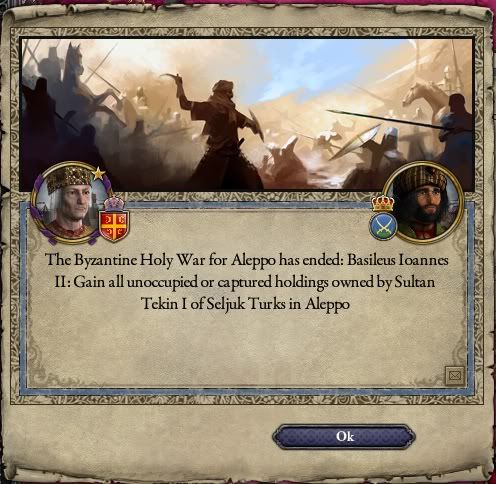

Not even a quick war to the West to secure Salerno with his ‘colleague,’ the Holy Roman Emperor, could assuage Ioannes’ fury. In 1247, the man the Saracens had labeled “Pale Death,” rode out of Constantinople once more at the head of 12,000 levies and the 6,000 strong Varangian Guard, intent on succeeding where the now long dead Doux of Chariason had failed—taking Aleppo from Saracen hands. For the first time, Ioannes tasted defeat—his column of 8,000 men was attacked by nearly double his number, led personally by the Caliph. Ioannes barely escaped with his life, and lost half of those men. The Emperor’s armies retreated in confusion to Antioch, where some advised Ioannes to abandon the campaign like the Doux had done long before.

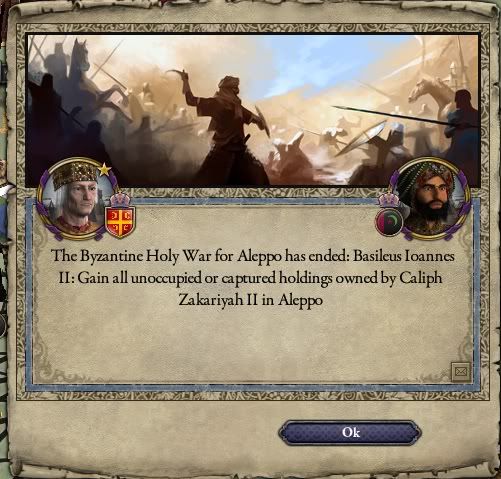

But Ioannes would not be dissuaded. Furious at being bested by a man he now regarded as a personal rival, the Emperor called up the levies of Chariason, Armenia and Samos, and by next spring he had three armies of 15,000 each pouring into the Emirate. Outside of Homs, the Emperor met the Caliph once more, but this time with an advantage of 18,000 to 10,000. Caliph Zakariyyah II’s army was slaughtered. After two more years of sieges, Aleppo and one neighboring county were secured and in the Christian hands for the first time since the Franks had been driven out 80 years before. In celebration, the Emperor named his youngest son, Andronikos, the new Doux of the region.

About this time a young man named Burchard von Chemigen came to court in Constantinople, appealing to the Emperor to aid him in regaining lands that were rightfully his. Ioannes was not inclined to listen to the blatherings of a mere German, until the lad mentioned the name of his title: Calabria. The region was the last portion of southern Italy not under imperial control, and had the potential to become a thorn in the side of the Empire there. Ioannes then agreed to press Burchard’s claim, if he bound himself as a Doux to be a true and loyal vassal to the True Emperor. Burchard agreed, and a 6,000 man expeditionary force quickly secured the region while the German kingdom fell into another civil war.

By 1255, Ioannes’ grandson and namesake had finally reached adulthood. He had a reputation for being quick to anger and slothful, but he was friendly enough. Ioannes had high hopes that his grandson would learn in Edessa how to navigate a ship of state. The future of the Empire rested on his shoulders.

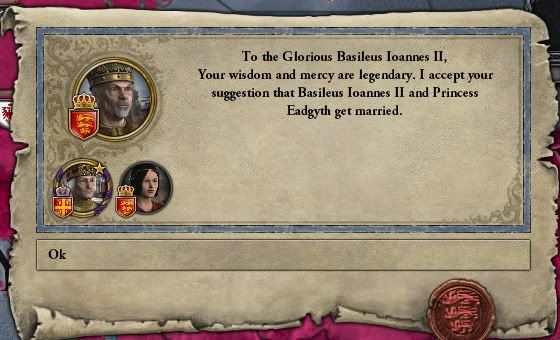

The young man’s grandmother, however, passed away during this time. According to Symeon of Athos, in his old age the Emperor had become a man “besot with the bedchamber,” with proclivities his elderly Empress, Margarita, could not handle. Thus, barely a month after her passing, the Emperor sent agents out across Europe, and by the month after they all had written of the beauty (and, allegedly, the skill) of Princess Eadgyth of England. Accordingly, Ioannis sent her father, King Estmond, a letter requesting her hand. He agreed, and the 55 year old Emperor was married to his 16 year old bride on September 6th, 1255. This union, and the children thereof, would bring nothing but woe for the Empire.

While the Emperor proclaimed a week of feasts in honor of his new wife, one of his vassals declared a week of preparation for war. Doux Konstantinos Murzophoulos of Achaia, appointed to the position in the place of a rebellious Doukas, was young, ambitious, and keen to make a name for himself. Wisely, he saw that striking against the throne would be foolish. Instead, as his advisors noted the weaknesses of the Sultans of Africa in Tunis, the Doux planned to strike at Cyrenaica, using his status as an imperial vassal as a shield to protect his homeland. Ioannis was informed of the Doux’s sailing in the midst of his wedding feasts—reportedly, the Emperor laughed and wished the headstrong young man the best of luck, but refused to send any other aid. From Ioannis’ perspective, an ambitious noble was kept busy, as was a Muslim power in Africa—all at little risk to the Emperor or his Empire itself.

Doux Konstantinos fought bravely and valiantly over the next two years, suffering defeat and deprivation outside of Benghazi, and triumph and victory outside of Cyrene. Coming under attack from Frankish crusaders directly assaulting Tunis, the Sultan finally agreed in 1257 to cede poor, pointless Cyrenaica to the Doux. From such hardscrabble beginnings, however, was the Murzophoulos legend born, and the seeds for the Roman Empire in Africa re-sown.

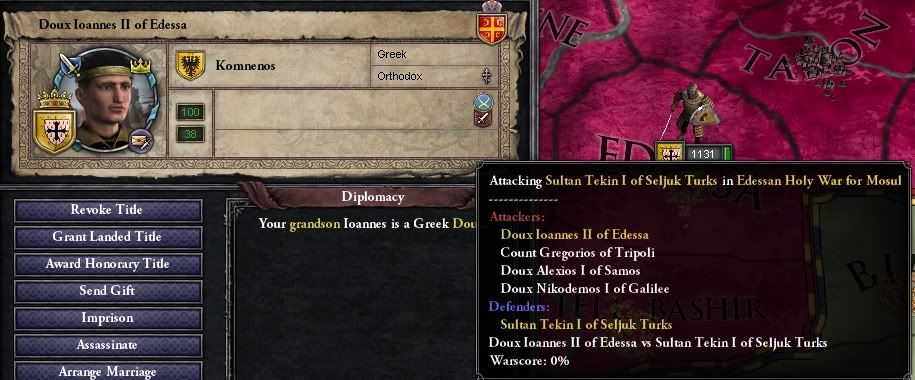

The Doux of Achaia’s success against Muslims, without imperial support, did not go unnoticed. In Edessa, young Prince Ioannis took note, and began collecting allies of his own. In 1258, he unilaterally declared war on the Seljuk Turks over the lands of Mosul. Despite the Doux raising a host of mercenaries, the Turks quickly destroyed his armies. Rather than surrendering, the heir to the Empire began to call in allies. By 1260, Edessa had been joined by Kartli, Armenia, Antioch, Galilee, Tripoli and Chariason—a force that should have been a vast and mighty host, save none of the Doux involved cooperated whatsoever. Instead of facing a united force, the Turks were faced with endless smaller columns attacking their lands piecemeal. The war went on for bloody season after bloody season, with the Emperor, by the laws of the realm, powerless to stop the useless waste of good soldiers and coin. Ioannis instead could only pray for his grandson’s continued safety, and make bloody plans of his own.

Far more was on the Emperor’s plate than just Mosul. Far to the north, another band of Mongols, calling themselves the Golden Horde, had thundered into the lands of the Rus. Taking a wide northern arc, they’d destroyed the Russian principalities of Novgorod and Perm, then the lands of the Finns, before destroying the enclaves of the Danes and the Swedes in Lithuania. Eventually, the Horde built ships and sailed directly for Danish and Swedish lands. Both kings by 1260 had knelt as vassals before the Mongol khagan in order to preserve their lives. While the Horde showed no inclination to go south yet, there was no telling if these new Mongols would stay their hands for all time.

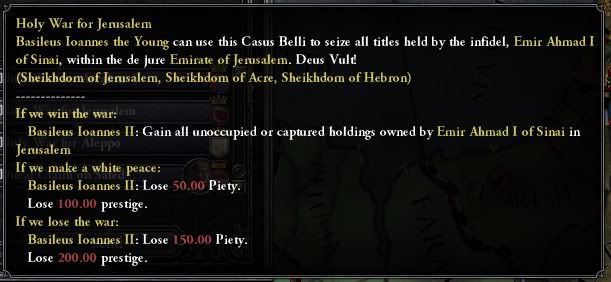

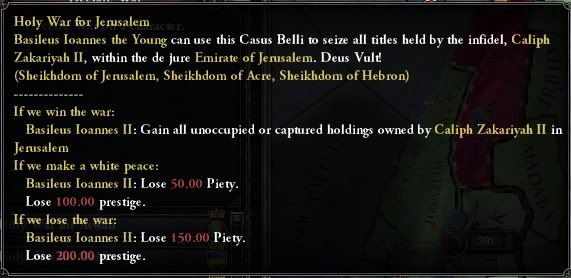

Edessa’s war for Mosul did serve another purpose, however—with the Seljuk Turks tied down fighting a motley assortment of Roman nobles, the slowly recovering Shia Caliphate, whole once more but still reeling from the long series of civil wars, had lost it’s most valuable ally in the region. The Emperor decided the time was ripe to press one last claim for the Holy City. No sooner had word gone out to muster the Varangians did a herald arrive in the Queen of Cities with urgent news—the great Ilkhans had converted to Sunni Islam. The Emperor’s war preparations reached a new fever pitch—it was only a matter of time before the Mongols, now motivated by their own religious cause, also sought to take the Holy City.

The Emperor mobilized the Varangians, his personal levies, as well as those of his loyal vassal the Doux of Nikaea to press the attack. In total some 30,000 men, in three armies, left Constantinople and Prusa, landing at Tyrus and marching south between March and May of 1261. Once again, Ioannis himself laid siege to the Holy City, with another force besieging Beersheb and a third at Ascalon. Caliph Zakariyah II once again proved a wily foe—he recruited mercenaries of his own, and managed to destroy the Doux of Nikaea’s army at Ascalon. The Emperor was forced to break off his siege, and unite with the Varangians to face the Caliph’s 15,000 in the field. The Battle of Nazareth was protracted, bloody affair, leaving 4,000 Romans and 8,000 Egyptians dead, but it broke the back of the Caliph. His armies retreated south, and the Romans were free to besiege the region, stronghold by stronghold. In December of 1262, a year after declaring war, the Caliph agreed to the humiliating Treaty of Acre, whereby Jerusalem was signed over to the Roman Empire. Bells pealed for joy throughout Christendom, while Islam went into mourning.

His life’s goal accomplished, in 1264 the increasingly infirm Ioannis finally turned his attention back to the still ongoing Edessan war against the Turk. Fearful that his grandson might suffer some horrible fate should the war go on too long, the Emperor resolved to force it to a conclusion. As the Turks held parts of the lands of the Doux of Aleppo, Ioannis declared war to recover the rights of his vassal. As an added menace, for the first, and only time in his reign, he called forth every vassal and banner available within the Empire, hoping to advertise his strength before a severe trial by arms. Almost immediately the Turks concluded a peace treaty with the Doux of Edessa, granting all his demands. Less than a month later, after Aleppo itself fell after a short siege, they agreed before the massed banners of the Empire to cede the Doux of Aleppo his rightful lands. It would be the Emperor’s last campaign.

Ioannis II, called “the Young” for taking the throne when only a few months old, suffered a fall during a hunt in 1266. Despite the best care, his broken leg refused to mend, and repeated infection and putrification set in. The Emperor’s physical condition rapidly deteriorated, but his mind remained sharp. He advised his grandson to come to Constantinople, and openly told him a list of men he thought would conspire against him. The younger Ioannis, confident in his martial skills honed against the Turks and feared by all, was sure that assassins would not be needed. It was advice the future Emperor should have heeded.

On July 13th, 1268, Ioannis II passed from this world. He died the most prestigious Emperor since Konstantinos Megas (12000+!), the Liberator of Jerusalem, a man both loved and feared by all. While not earning it, few would doubt that the late Emperor deserved such monikers as “the Conqueror” and “the Great.” His grandson, now Ioannis III, would come to the throne seeking to rise out of that immense shadow.

Alas, it was not to be…

OUTSIDE OF GAME: So ends Ioannes II’s ridiculously long (and successful) run as Byzantine Emperor. I used the same tactics I did while playing the Byzantines in the original game—I waited for the Muslim powers nearby to fall into civil war, and then picked at them with my personal levies, and avoided stirring my vassals as much as possible. In retrospect, the second marriage to Eadgyth was a mistake… you all will shortly see why.

The War for Aleppo with the Turks was solely done on my part to force an end to the Mosul mess. I didn’t want my heir being killed or maimed by a Turkish arrow before he got to inherit, obviously. And the war went pretty much as described… I mobilized the entire Empire mostly out of curiousity at seeing that sum of soldiers in the ledger. No sooner had I taken a castle with my army did the Turks surrender. Maybe the difference in mobilized soldiers influences how quickly the AI sues for peace?

And yes, the Golden Horde decided to rampage Scandanavia, of all places. For the life of me I cannot fathom how, or why. When they appeared, I almost assumed they’d head across Russia and then turn south after me. That the Khagan ends up in Copenhagen still makes me laugh.

And for the record, here is the Roman Empire in 1206, when Ioannes was still under a Regency as a 7 year old:

Territory wise, the Empire had actually shrunk since its height under his grandmother Anthousa Doukas. Here is the Empire on the day of his death, in 1268:

Huzzah! The Empire stands at its greatest extent in six centuries, and even has lands in Africa thanks to the resourceful Doux of Achaia! So Ioannes has built everything up, next we’ll get to see how well this edifice stands against a whole slew of threats, chief of which is

bad luck.