Paris ne vaut pas une messe! - A Huguenot IN AAR

- Thread starter Milites

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Haha, I thought you were English through and through with your Cromwellian emperors and what not

No, I'm of almost pure German / Swiss ancestry. Just a few bits of French and Irish* mixed in for good measure.

*Note: Irish and Cromwell... don't mix well.

Enewald said:The German one is a bit too grey methinks.

It's Prussian Germany under the Kaiser. It must be grey. Grey is an ordered, disciplined, emotionless colour, after all.

*Note: Irish and Cromwell... don't mix well.

No matter how the various timelines in alternate history differs from that of the original, I guess this will always be the case

It's Prussian Germany under the Kaiser. It must be grey. Grey is an ordered, disciplined, emotionless colour, after all.

Absolutely!

Congrats on the ghost pages! Or have they been here for awhile?

They've been there for a while, yet there doesn't seem to be much one can do about it. The moderator I contacted, didn't seem to know any method anyway. It's pretty annoying though... messes up the index of updates

I have been following this AAR from the beginning, but haven't ever commented, since I usually just read on forums and rarely write.

Well, but I just wanted to say that this AAR is one of the best I've read (and again I've read many). Not only because of the beautiful pictures and maps, but also the great writing, whether the history book-style or the fictional scenes. I have been really enjoying it. So, keep up the great work!

Aaaaand I wanted to point something out. About the picture of Don Carlos from the last chapter which you found "on the Swedish wiki". It's actually Martin Luther, disguised as "Junker Jörg", during the time he was outlawed by the emperor.

About the picture of Don Carlos from the last chapter which you found "on the Swedish wiki". It's actually Martin Luther, disguised as "Junker Jörg", during the time he was outlawed by the emperor.

Sorry for being a smartass, but I just had to point that out. o

o

And I guess, it's even more ironic, the (military) leader of Catholic Spain looking like Martin Luther...

Well, but I just wanted to say that this AAR is one of the best I've read (and again I've read many). Not only because of the beautiful pictures and maps, but also the great writing, whether the history book-style or the fictional scenes. I have been really enjoying it. So, keep up the great work!

Aaaaand I wanted to point something out.

Sorry for being a smartass, but I just had to point that out.

And I guess, it's even more ironic, the (military) leader of Catholic Spain looking like Martin Luther...

As an even lurkier lurker I have to echo the comments of 0Emmanuel. This is a particularily fine AAR that you obviously put a lot of work into and I felt that I should note my appreciation. I find it particularily interesting as I have a real interest in the Reformation period, see my sig.

Aaaaand I wanted to point something out.About the picture of Don Carlos from the last chapter which you found "on the Swedish wiki". It's actually Martin Luther, disguised as "Junker Jörg", during the time he was outlawed by the emperor.

Ha! I feel vindicated now

Milites, I must say your work on those skins are beautiful! Almost as beautiful as this AAR of yours!

I have been following this AAR from the beginning, but haven't ever commented, since I usually just read on forums and rarely write.

Well, but I just wanted to say that this AAR is one of the best I've read (and again I've read many). Not only because of the beautiful pictures and maps, but also the great writing, whether the history book-style or the fictional scenes. I have been really enjoying it. So, keep up the great work!

Thanks a bunch! Luring lurkers out of their lurking lurkiness is a great pat on the back for any writer

Aaaaand I wanted to point something out.About the picture of Don Carlos from the last chapter which you found "on the Swedish wiki". It's actually Martin Luther, disguised as "Junker Jörg", during the time he was outlawed by the emperor.

Sorry for being a smartass, but I just had to point that out.o

And I guess, it's even more ironic, the (military) leader of Catholic Spain looking like Martin Luther...

I feel... strange. I must commit seppuko as a way to atone for this mishap

As an even lurkier lurker I have to echo the comments of 0Emmanuel. This is a particularily fine AAR that you obviously put a lot of work into and I felt that I should note my appreciation. I find it particularily interesting as I have a real interest in the Reformation period, see my sig.

The reformation is, in my opinion, probably the most interesting period in human history because of all the minor streams of religious reformation movements combining into the disastrous 30 Years War.

Ha! I feel vindicated now I would have recognised Charles V if nothing else for his Habsburg jaw. I'm sure Milites will be happy to know the true identity of the portrait, though

You couldn't know that I had made mistake in choosing the portrait... happy isn't exactly the word I'd use to describe my current state of mind

Milites, I must say your work on those skins are beautiful! Almost as beautiful as this AAR of yours!

Haha, thanks I guess XD

Anyways guys, there'll hopefully be an update ready for Tuesday. So stay tuned for new posts in this thread.

[2]A reference to a Huguenot propaganda leaflet distributed during the Wars of Religion that pictured Henri IV as a Hercules. http://www.lepg.org/hercules.htm. Henri IV was also referred to as le Vert Gallant [the Green gallant] although the meaning of this eludes me.

[/INDENT]

I just stumbled on something in Encyclopædia Britannica, while completely unrelatedly reading up on Henri IV. According to EB, and backed up by French Wikipedia, a "Vert Gallant" means a person who is very *ahem* active for his old age. Henri was given this nickname because of his many amourous adventures.

Last edited:

Well the appetite of Henri IV when it came to spending time with the fairer sex is pretty well known  If my memory doesn't betray me outright, I seem to remember that he (in the original timeline) after the Battle of Coutras decided to go back to Béarn in order to spend more time with a mistress instead of utilizing the gains the victory gave him

If my memory doesn't betray me outright, I seem to remember that he (in the original timeline) after the Battle of Coutras decided to go back to Béarn in order to spend more time with a mistress instead of utilizing the gains the victory gave him

But as for the promised update, I'm terrible sorry, but given its extraordinary nature it has been postponed until the author finds it in his heart to send me it (the update, not his heart).

But as for the promised update, I'm terrible sorry, but given its extraordinary nature it has been postponed until the author finds it in his heart to send me it (the update, not his heart).

Stunning background skins you've made for Kaissereich! and of course a wonderful AAR

Many thanks

And Jesus I just realized that there's only been one update all October :/ I'll try to remedy the situation at double pace now (as it seems that the guest chapter has been postponed, again).

Next chapter will include the obligatory chapter introduction picture, three maps and two other illustrations as well as a, slightly easier, Calvinist quiz.

So stay tuned!

And Jesus I just realized that there's only been one update all October :/ I'll try to remedy the situation at double pace now (as it seems that the guest chapter has been postponed, again).

Next chapter will include the obligatory chapter introduction picture, three maps and two other illustrations as well as a, slightly easier, Calvinist quiz.

So stay tuned!

as well as a, slightly easier, Calvinist quiz.

Yay! Calvinist cookies are in the oven!

I just skimmed through this thread, Milites, and I must say I hate the fact that I don't have a time to read it properly. Who said that student's life is easy? I want to shoot the guy!

Anyway, great graphics, you should do it for the living

Anyway, great graphics, you should do it for the living

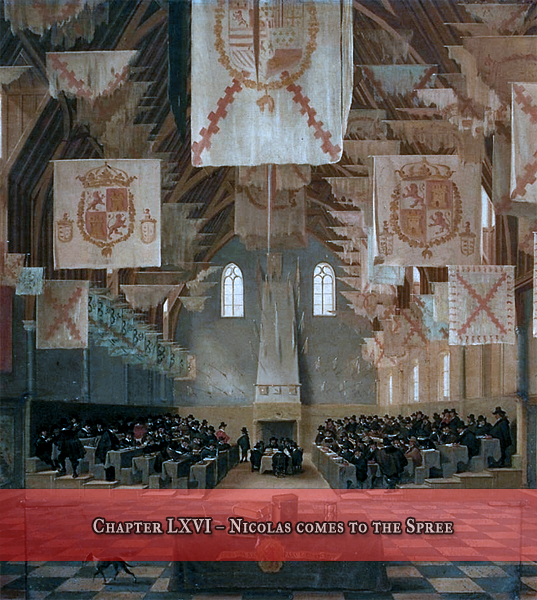

Chapter LXVI – Nicolas Comes to the Spree

When a sovereign of 17th century Europe decided to marry, he did not do so primarily with the modern intent of securing personal happiness, but more likely with the goal of furthering the cause of the state. Countless examples exist throughout early modern history where marriage between the ruling houses of the day were made to secure or strengthen alliances, pacts and treaties concluded by the states over which the dynasties in question ruled.

Sometimes the odd incident did occur, where the prince wed his princess despite there being more favourable brides available on the market so to speak. More often than not though, such irresponsible behaviour tended to create great amounts of resentment between the officers of the state and their monarch as they (the officers) saw such romantic devotion as nothing but egoistic contempt for the interests of the state.

In the case of Nicolas Henri we are left with a curious example wherein both the modern ideals of a love-driven marriage and the state-focused concept of holy matrimony of the 17th century are wielded together. Nicolas stood as one of the grandest rulers of Europe, the champion of the Calvinist faith and a serious claimant to the title of Holy Roman Emperor when he began his quest for a suitable wife upon whom a certain form of responsibility, whose importance under no circumstances should be ignored, would also lay. This responsibility that would bother any potential wife Nicolas were to choose refers, of course, to the fact that she would be expected to be able to produce a healthy heir who could succeed his father and thus ensure stability within the realm in a swift and unproblematic succession.

Therefore it is not unjustified to think of Nicolas as the dream of every young princess of the day and age, given his vast holdings and prestige. But the king of France was also a quite particular man when it came to the fairer sex and by his 23rd birthday he had already had numerous affairs with mistresses from both domestic and foreign aristocratic families all over Europe, a trait he most likely had inherited from his father, the well known Vert Gallant.

But despite his love for short, non-obliging romantic relationships, Nicolas understood the political importance of marriage and as his greatest goal was the campaign for the crown of the Holy Roman Empire he decided it would be best for both his own ambition and the interest of the state that he sought a spouse from the vicinity of the Empire. However, he also wanted to stabilize his relationship with the Protestant princes who made up his supporters amongst the Imperial Electors and as such any Catholic princess was out of the question.

One option was to marry one of the incumbent (albeit completely outmanoeuvred) emperor Anton’s relatives, but given the fact that the emperor was rapidly on his way towards a confrontation with his relatives the Oldenburg kings of Denmark-Norway (alongside the house of Vasa another major Protestant power in the north) over the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein this was also quickly discarded. Other options could be to engage with members of the houses of Stuart and Orange-Nassau, however, the two powers were in no way influential within the Empire.

This left only one other suitable power in Northern Europe from where Nicolas could find a fitting queen to rule alongside him, namely the Electorate of Brandenburg-Prussia ruled by the house of Hohenzollern.

Just the simple fact that Brandenburg was an electorate was enough to satisfy Nicolas as it would all but guarantee the support of one of the most influential Electors in his quest for the title of Emperor; yet other factors also made the German dominion an interesting target for finding a matrimonial possibility. Amongst those the most important one was the status of religion in Brandenburg, for by 1630 the majority of the noble families had followed the Elector’s example and converted to Calvinism, whilst any attempt at forcefully converting the common populace from Lutheranism had failed following massive protests. The result was a state where Lutherans and Calvinists lived side by side[1], something that certainly appealed to the Calvinist Nicolas who relied extensively on support from princes confessing to both branches of the reformation within the Empire’s borders.

Even if all these advantages spoke in favour of marrying into the house of Hohenzollern, it’s highly plausible that nothing would have come of the marriage had the women in question not been to the young king’s liking. However, it quickly became clear that Maria Eleonora, daughter of Elector Sigismund Hohenzollern, was no ordinary princess.

Eight years his senior, Maria was at the time of Nicolas’ proposal still perceived to be the “most beautiful princess of all Europe”[2] and her stunning looks are said to have brought even jealousy to the Queen of Spain. Nicolas who had spent most of his youth in the care of the regency of Sully, notably together with marshal de Bonne, was immediately drawn to her very feminine appearances (although this did cause some concern that she was “not very intelligent”[3]).

Despite the doubts his advisors might have held against the Brandenburg princess, Nicolas soon made up his mind and after a rather short romantic affair, which was centred both in Berlin and in Paris, the couple married just two years after Nicolas Henri’s ascension to the throne (1628) under much fanfare and glamour in the cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris.

Nicolas settles down (1630)[4]

However, the marriage was not completed without protests from the court of Brandenburg where Maria’s own brother and then current elector, George William, resented his sister’s choice as it would have put him greatly at odds with his liege Albrecht IV and thus potentially shipwrecked his goal of transforming the Duchy of Brandenburg into a kingdom. Luckily for the two lovers it was tradition in the duchy that the princess’ mother held the final say in matters of holy matrimony - and what George William failed to see, his mother, on the other hand, perceived quite aptly. She concluded that the time of Albrecht would be short (and granted, he was assassinated 6 years after the wedding of Nicolas and Maria) and that France soon would take the place of the Habsburgs, which in turn would logically mean that the safest bet for support in winning a royal crown for the Hohenzollerns would be to take the side of France.

Sadly George William didn’t take his mother’s intervention well and continued to hold a grudge against her and his sister until his own death in 1640 (meaning that Nicolas couldn’t have hoped for his support in the heated Imperial election of 1636 even if there had been no allegations against French involvement in the murder).

Although their marriage might not have resulted in the bullet-proof Brandenburg vote that Nicolas needed so badly in the elections that brought the dukes of Holstein, Anton and Karl Ludwig, to a shaky position as emperors, the union did, in the long run, create the needed coalition amongst the Protestant princes Nicolas needed, but this was as much thanks to the success of the Huguenot armies as it was owing to the fact that George William’s successor realised the great amount of potential an alliance with France could bring his duchy.

Maria’s nephew and George William’s heir, Frederick William, (later known as the Great Elector) was a brilliant politician and field commander who understood, as his grandmother had, the potential which a Bourbon emperor could provide and as such he abandoned the policy of neutrality which his predecessor (and to a certain degree himself as well given his initial support for Karl Ludwig) had pursued and gave his “dear uncle” his full support during Nicolas’ war against the Iron Cardinal and Don Carlos.

This support did at first only show itself through a standing offer from the Elector to Nicolas regarding a potential “lease” of several German regiments and material by the French army, but as the Huguenots and their auxiliaries advanced into Bohemia and Austria Frederick made his move. With blessings and guarantees from the Louvre, the duchy’s government in Berlin decided to capitalize as much as possible on the simultaneous weakness of Imperial authority and the turmoil that engulfed the neighbouring duchy of Pomerania by dispatching two armies into the eastern parts of the Baltic state (mid 1655), catching the Griffin dukes by complete surprise.

The Elector’s forces made short work of the defending forces whilst Karl Ludwig didn’t even bother to issue any declarations against the aggressors. Sweden and Denmark-Norway now both intervened against the Duchy of Pomerania, hoping that they could seize the western parts of the duchy which held the valuable cities of Stralsund and Rostock for themselves. However, the superior Danish navy made sure that the Vasas’ expeditionary force never even got sight of the Baltic coast, bringing the two Scandinavian kingdoms dangerously close to a war that easily could have spread all the way to Russia. Yet by the time the Protestant League under Turenne was engaging the Austrians outside Linz (March 1656) Danish forces had taken the island of Rugen, effectively dividing the possessions of the Griffin family[6] between the Oldenburg State and Brandenburg. At this the Swedes were of course outraged and Gustav II Adolf contemplated a withdrawal from his Polish affairs in favour of a landing on the Baltic coast whilst the French were busy in the Habsburg Erbländer. But by then, Frederick William’s cousin, the dauphin of France and son of Nicolas and Maria, arrived at the elector’s camp in Kolberg with a large sum of currency and several Huguenot delegates – sending a crystal clear message to the Swedish monarch to leave the Pomeranian lands well alone.

Domains of Brandenburg in 1661 with Hinterpommern and Altmark (excluding the Prussian lands, who were de jure parts of Poland).

But who was this French prince who came to the Baltic shores loaded with coin and materials for his campaigning cousin who had such ambitious goals? Well the obvious answer would be, “he’s the dauphin of France, the heir apparent and consequently the son of Nicolas I Henri.

King Nicolas and his wife Maria were very much in love for the first years of their life, the King obviously enjoying the devoted attention which his intelligent (as the Baltic princess proved quite smart, in spite of her emotional tendencies) wife gave him. As such is it of little wonder that the pair at some point would produce a child, but that Nicolas’ legitimate firstborn would be a healthy boy with dark brown hair surpassed most of the court members’ expectations.

Louis, named in honour of the King’s murdered brother, grew up in a curious world where the sophisticated stage of the Louvre constantly was being exchanged with a rough life on the road from one military camp to another – at one point he would be safe and protected with his nurses and tutors and at another he would be inspecting troops alongside his father’s generals at the banks of the unforgiving and cold Rhine. It is universally agreed that a young child needs stability and calm surroundings if it is to evolve “properly”, but despite this early life of trips from balls to barracks, the dauphin was actually empowered and strengthened for his later role as the nation’s helmsman. He could, at the blink of an eye, change from joyful and jovial to harsh and aggressive – if the circumstances demanded it.

However, what affected Louis the most during his early years was without a doubt the events of the Second Fronde (1639-1643) where he and his mother found themselves practically isolated in the capital with rebellious nobles surrounding the countryside. If Nicolas had been upset by the uprising undertaken by his brother Gaston, the minister Rohan and the marshal Duc d’Enghien it was nothing compared to the pain it caused young Louis who had thought of the three men as a solid bastion of fatherly figures when his own patriarch was away at the front.

Once the demands of the Frondeurs had been satisfied and peace had been restored to the kingdom, Louis made the solemn vow of never allowing anyone to betray him. His relations with the other boys at court soon deteriorated when it became clear to them that he didn’t trust them to the same as before. As a result, the dauphin had few true friends and spent most of his time in the company of his father’s officers.

Yet the dauphin grew up to be a fine young man well versed in both intellectual debate (something undoubtedly owing to the teachings of his moderate Catholic tutor, René Descartes, who had fought in the army of Maurice of Nassau[7]) and martial and strategic arts – and as such he quickly became enrolled in the day to day running of the state, paying regular visits to the treasury and ministries of war. This brings us back to Brandenburg where he held his first military commission in the Hohenzollern army of his cousin as a commissioned officer in a cavalry squadron. The fighting in Altmark and Pomerania brought him some acknowledgement and his cousin, the Great Elector, often wrote letters of recommendation to his aunt the Queen of France wherein he praised the young prince for his organisational skills and courage – although criticism was also found, mostly concerning Louis’ liberal courting with the young noblewomen of the Berlin court.

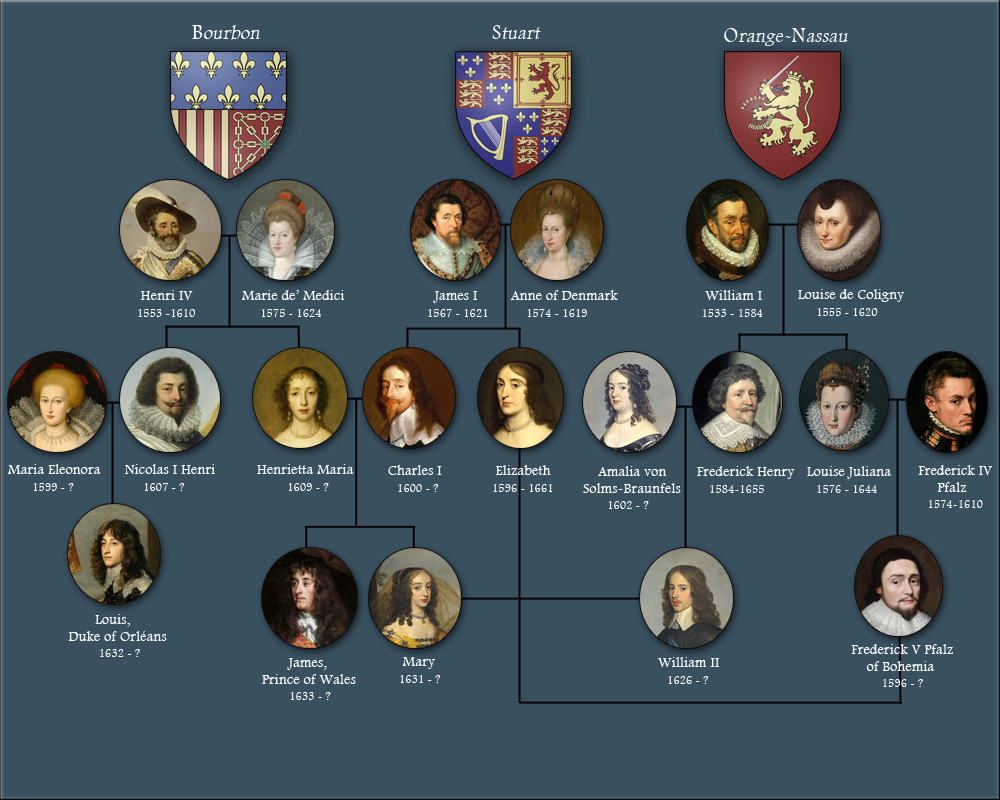

The intermingling of the three “Great Protestant Houses” in 17th century Europe.[8]

The Bourbon-Hohenzollern marriage was extraordinary in the sense that Nicolas had bypassed a chance at strengthening his ties with the nobilities of the United Provinces and Stuart-controlled England-Scotland, however as time went by it became clear that the three great Protestant powers were drifting away from each other at alarming speed. If one combines this with the lack of interest the two powers had in the internal development of the Holy Roman Empire, it becomes clear that a strengthening of the Franco-Anglo-Dutch relationship wouldn’t be able to further the cause Nicolas was pursuing – the Imperial crown.

The three great houses were intermingled through several important arrangements which in itself weren’t very surprising given the close bond the three states had enjoyed. However, although Nicolas’ own sister, Henrietta, was married to the King of England and that the Prince of Wales thus was the cousin of Louis the House of Stuart was far more connected with the princely family in the Dutch Republic, thus cementing a close alliance (despite contradicting interests in international trade).

Charles’ sister had married the future king of Bohemia, Frederick V Pfalz who himself was the son of the Dutch Stadtholder Frederick Henry’s sister and the count of Pfalz, Frederick IV. This had not only brought the houses of Orange-Nassau and Stuart closer, but it had also drawn the Elector Palatinate closer to them. That Nicolas provided crucial support for Frederick’s claim to the crown and the fact that the Elector’s wife, Elizabeth, died in 1661 did, however, reduce the Palatinate’s connection with London and Amsterdam significantly.

Yet the most crucial union between the two naval powers was the marriage between Mary Stuart and the young Dutch Stadtholder William which meant that the young couple had become a dangerous brick in the game for the English throne as many British noblemen would rather prefer a Dutch over a half French as monarch.

The reason for this fear was that James, the Prince of Wales, had spent most of his young life in the care of his Huguenot mother who held a disdain even higher for the English parliamentarian system than her husband or even her father-in-law had and as a result, the severely weakened nobles and parliamentarian supporters still left in England feared James and his radical absolutist mind as well as his tendencies to favour Huguenot service instead of the Anglican communion.

Political allegiances of some town in England and Wales around 1661.

During the uprisings in East Anglia at the time of Charles invasion of Parliamentarian Ireland, it had become clear that royalist support was dwindling under the strain from continued warfare with France’s enemies and more and more dissenters were being rounded up and put in the Tower, or if they were unlucky on a pole at the capitals ramparts (although the majority was simply sent into exile in the colonies or Scotland).

London itself had to be garrisoned thoroughly with both native royalist regiments, but also with mercenary companies from France and the Palatinate – something the local populace didn’t look kindly on and fuelled the parliamentarian underground opposition’s propaganda efforts.

In an effort to definitely quell any risk of armed revolt, the King created four military districts centred around Chester and Bristol (in order to keep Wales sealed of off) Norwich and York where the latter soon became so fortified that it became known as “The Key to Scotland”.

Royalist cities were mainly situated in the south-east with Oxford as the place wherefrom most of the king’s men were recruited, although a notable exception was the city and fortress of Pontefract (named as a reference to the support given by the original supporters of James I to his son Charles) which “…stood as an impenetrable cliff in a sea of rebellious waves…the strongest inland garrison of the Kingdom.”

The parliamentarians on the other hand began to enjoy wide support quite literally in all corners of the Kingdom of England-Scotland although the south of Cornwall became their most formidable popular strongholds.

[1]All of this actually happened in OTL

[2]Again, a historically correct description of Maria

[3]Being too emotional (e.g. being strongly in love) was at this point in history, and especially regarding women, not a good sign of a rational mind

[4]Yeah, I know. It’s an old screenshot, but I wanted to keep Nicolas’ marriage as a treat for the post-war European scene.

[5](Election of 1636)

[6]No, this is NOT the family I’m referring to…

[7]Also historically correct.

[8]Calvinist Quiz! – The monarchs portrayed in the above picture all have correct portraits (I hope >.<) except for two of them, who are double gangers. Name the nobles with wrong portraits and get a cookie (and if you’re really hardcore, you’ll be able to tell whom their portraits actually depict!). This of course excludes Nicolas I Henri and the dauphin Louis as the former never lived into manhood in the original time line let alone had a son

Last edited:

William I and Frederick IV?

Ah, scratch that. That is the right William.. I seem to recall a portrait of some Italian fellow looking remarkably similar. I'm guessing the other is Frederick's wife, aye?

Ah, scratch that. That is the right William.. I seem to recall a portrait of some Italian fellow looking remarkably similar. I'm guessing the other is Frederick's wife, aye?

I'd say Friedriech IV and his wife are both fakes. But I have no idea who the portraits really depict.

Vert Gallant...

Vert Gallant...