Chapter CXVI: The World at War – Act Three ‘The Curse of Maximus’

(1 January 629 AUC/123 BC to 6 February 630 AUC/122 BC)

Introduction

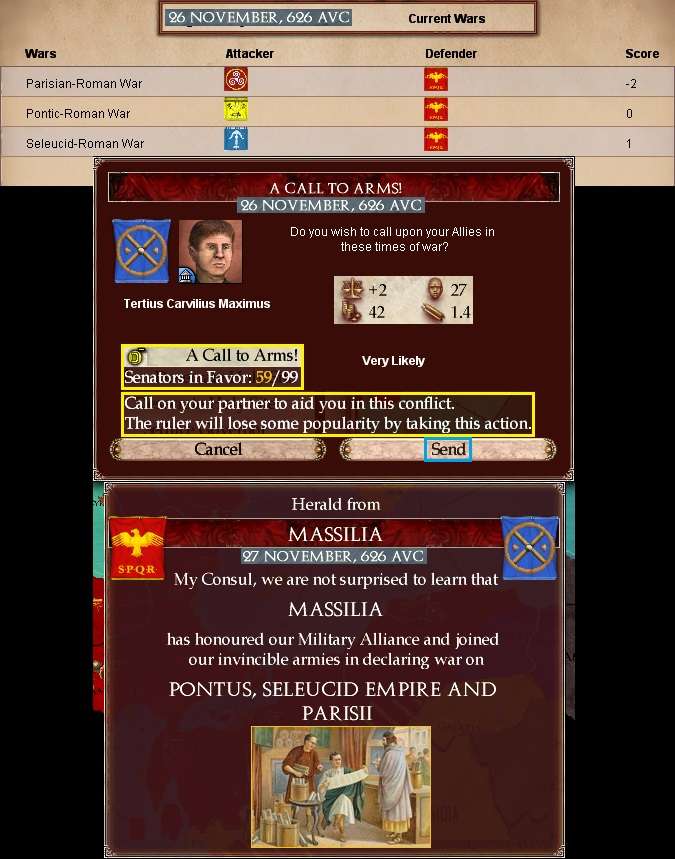

The Great War against Pontus and the Seleucids dragged on in the east, with Rome currently evicted from Asia Minor and the campaign still running hot on the Euxine Front. However, the opportunistic Parisii had been defeated and forced to yield most of their holdings in northern Gaul as punishment for their treachery.

§§§§§§§

1. The East: January to June 629 AUC

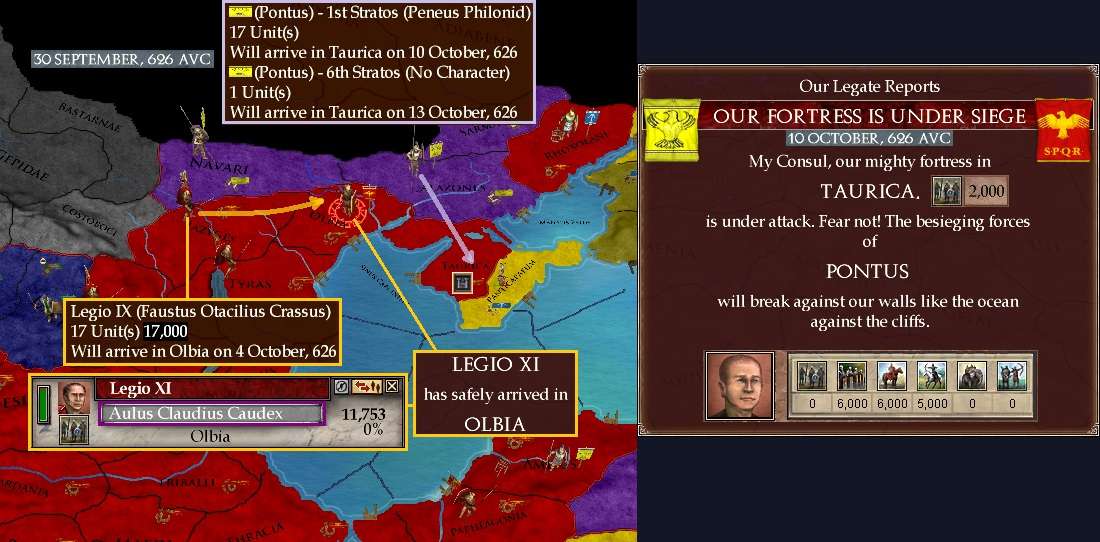

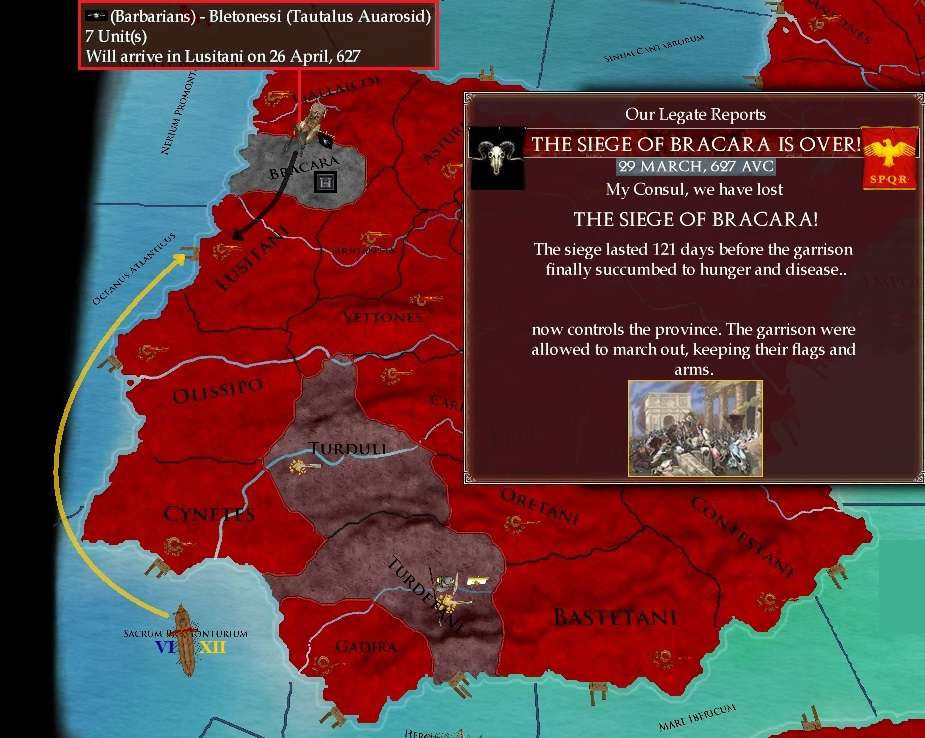

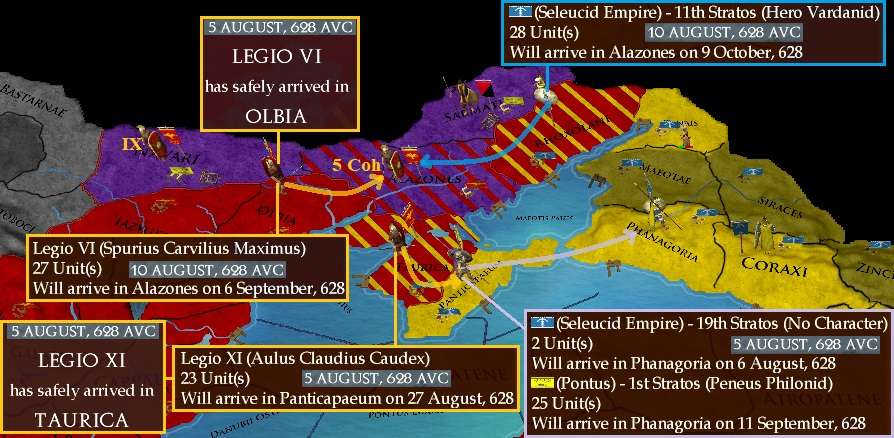

In the north, the previous year had ended with F.O. Crassus taking Legio IX to invest the Pontic-owned but rebel-infested province of Sarmatia. The redoubtable A.C. Caudex (Legio XI) and one of the many S.C. Maximuses (the older one, Legio VI) were on the march from Alazones to see if they could retake Rhoxolani, while sending a small siege detachment south to retake Taurica.

By 4 January, the enemy response was clear: the Pontic 1st Stratos (25 units), plus the Seleucid 2nd (28 units) and 22nd Stratos (19 units) were all heading west to Rhoxolani from Tanais, where they were due to arrive on 13 February – just three days after the Romans were due to get there themselves.

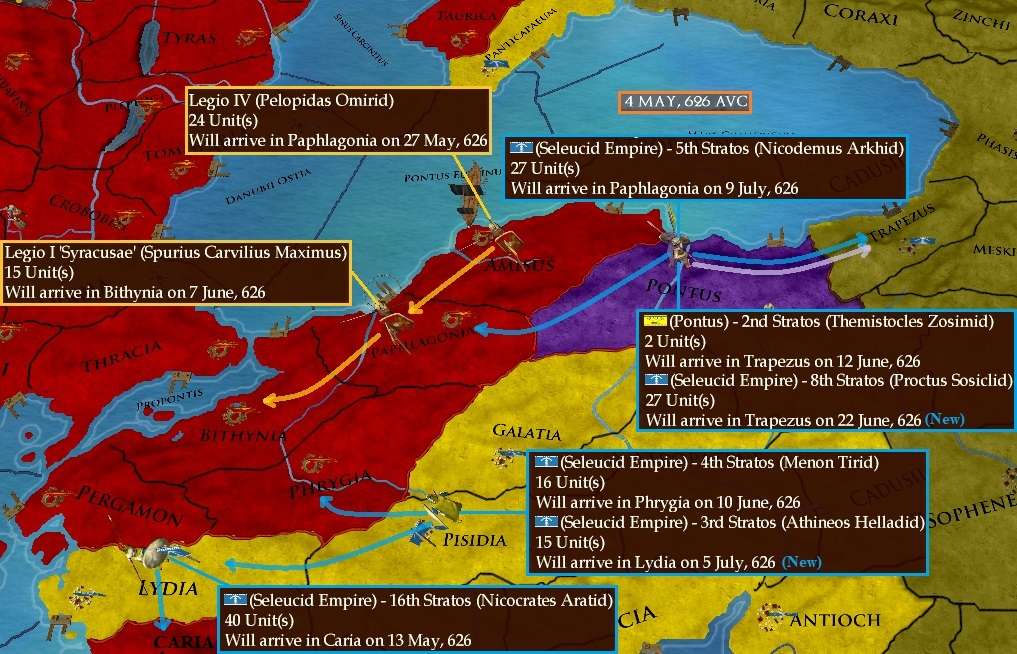

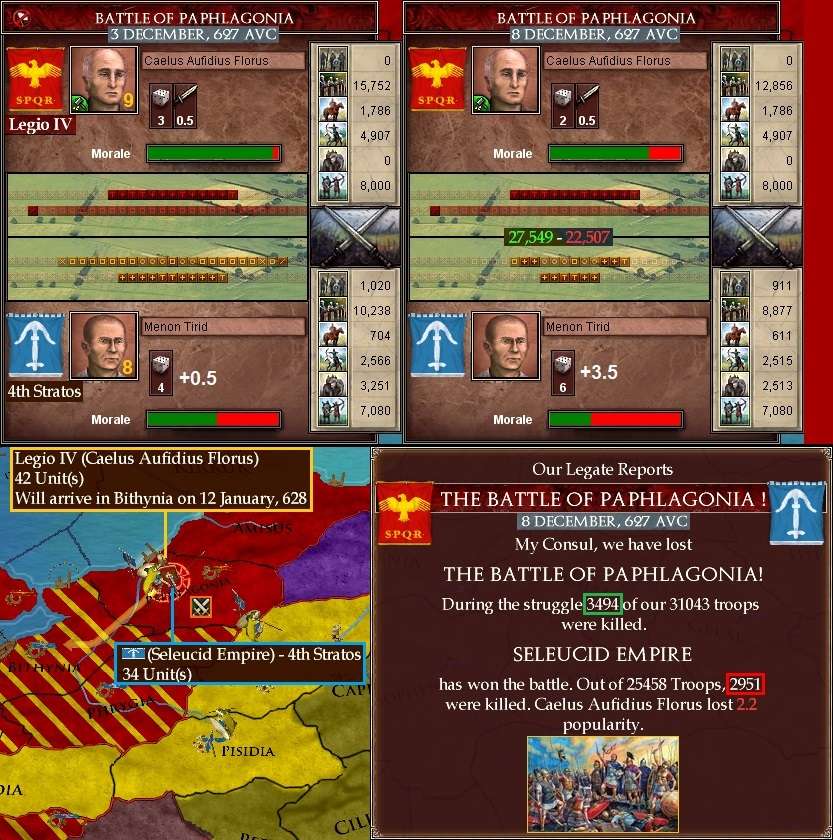

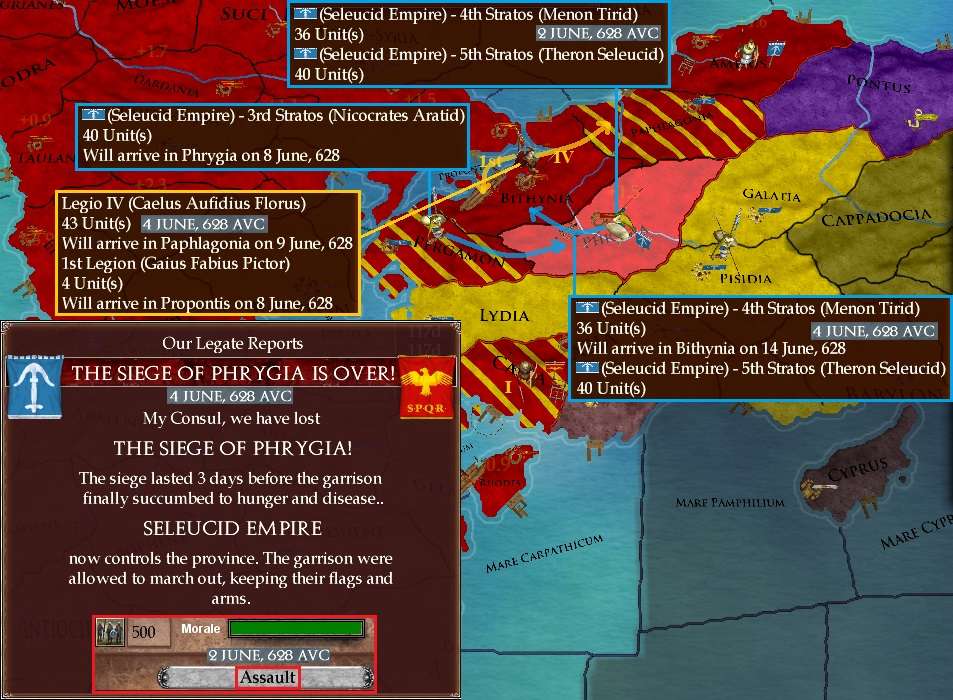

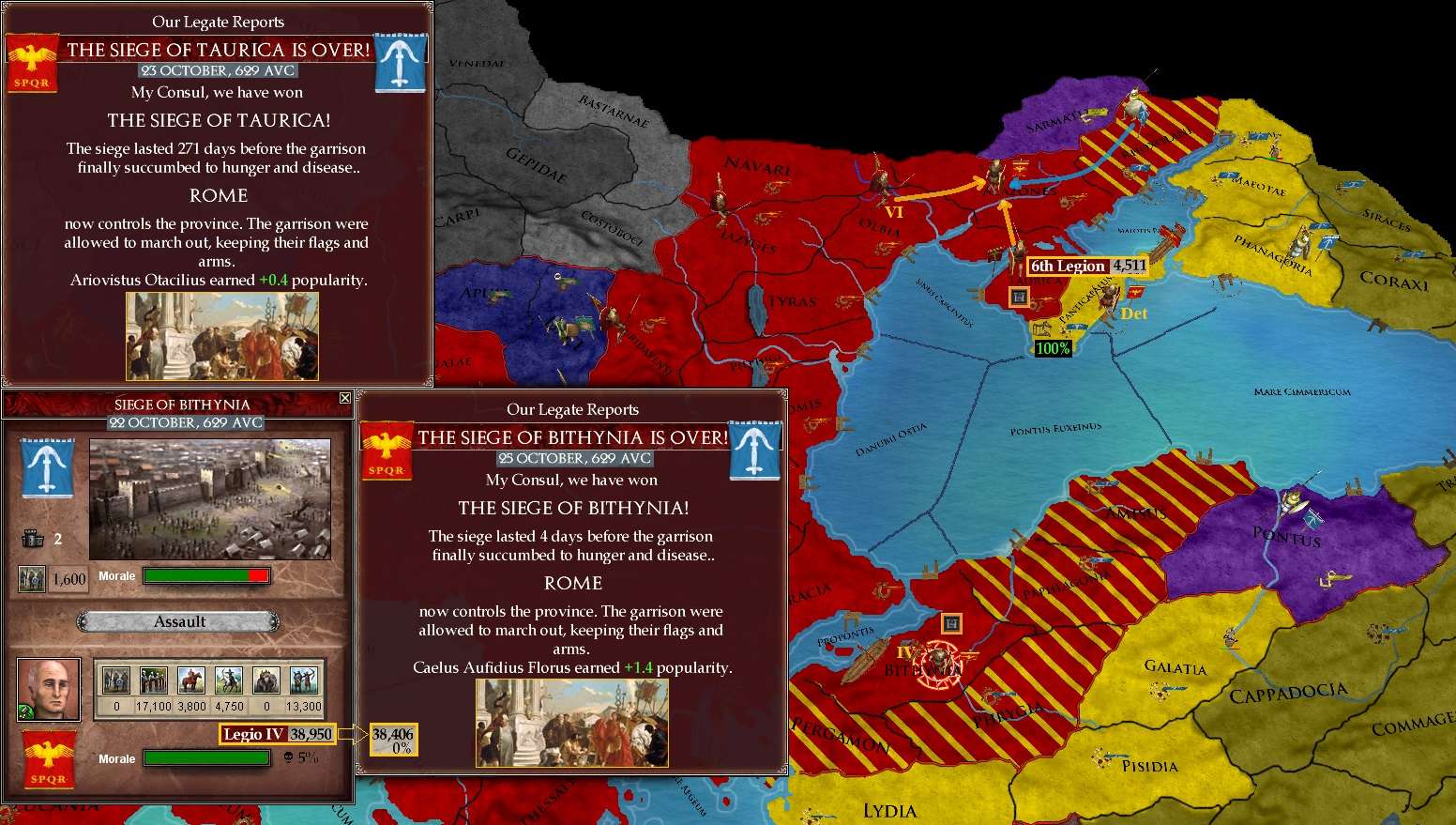

After the destruction of Legio I in Lydia, lead Roman commander in Asia Minor Caelus Aufidius Florus had fled from Pontus and was now rebuilding Legio IV in Thracia, safe behind the Roman Navy’s blockade of the Propontis. On 20 January, Legio IV (40 cohorts, 30,700 men) began a ‘slow crossing’ of the Propontis to Bithynia. At that time, there were 34 Seleucid (12th Stratos) units in in Pisidia and 101 (4th, 5th and 17th Stratos) in Pontus (mostly heading east towards Trapezus). But none either in nor heading directly to any of the occupied Roman provinces of Asia Minor. Thus Florus had decided to try his luck.

Legio IX arrived in Sarmatia on 28 January and wiped out the rebels there in a single day (Rome 174/16,009; Rebels all 3,000 killed), then was fortunate enough to be able to take over the rebel siege lines

[100% progress].

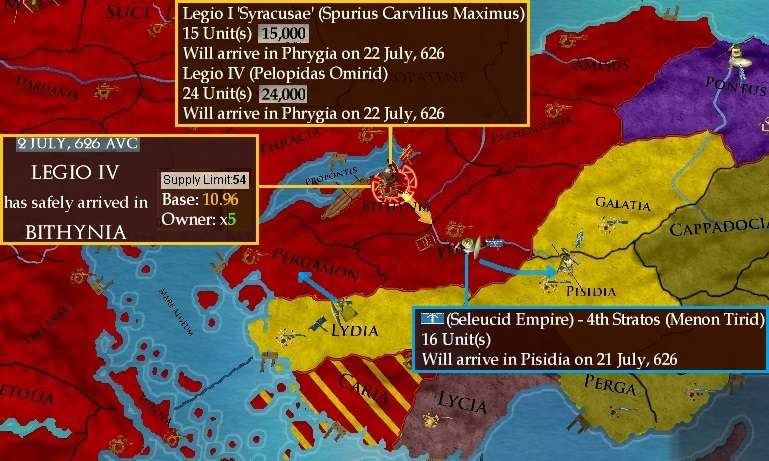

In Asia Minor, on 31 January 12th Stratos was spotted marching into Phrygia, where they were due on 1 March. But Legio IV kept going: it was a race to see if they could get to Bithynia first, otherwise they would face a naval landing penalty. All the other Seleucid armies were now making for Trapezus – it seems they had decided the Euxine Front was now going to be the key battleground.

On 2 February, the Roman manpower reserve was 88,338, with 35,880 replacements required. A week later, A.C. Caudex once again had his hand out for a ‘loyalty payment’: very well timed on his part, as he was due to join battle with the enemy in Rhoxolani the very next day! The money was handed over.

I certainly hope he’s worth what he believes himself to be worth, thought Bernardius darkly as he signed over 100 gold talents of ‘management overheads, facilitation payments and miscellaneous expenses’ to the care of Caudex’s

factotum.

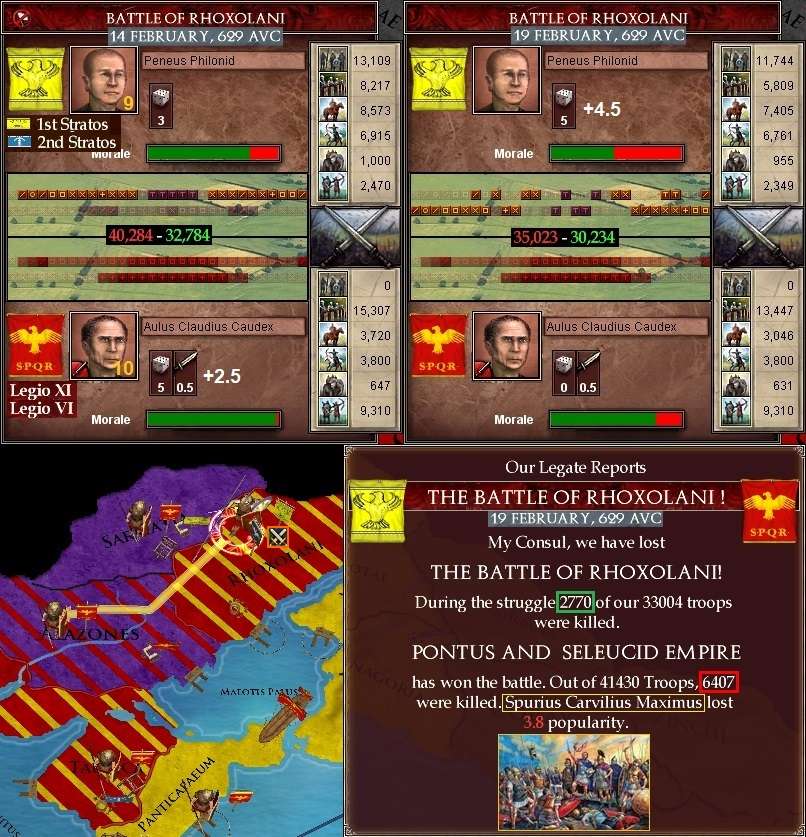

By now, one of the Seleucid armies had split off to march south, with a combined Pontic and Seleucid force of 53 units still heading towards Caudex’s army of around 33,000 men that had just arrived in Rhoxolani.

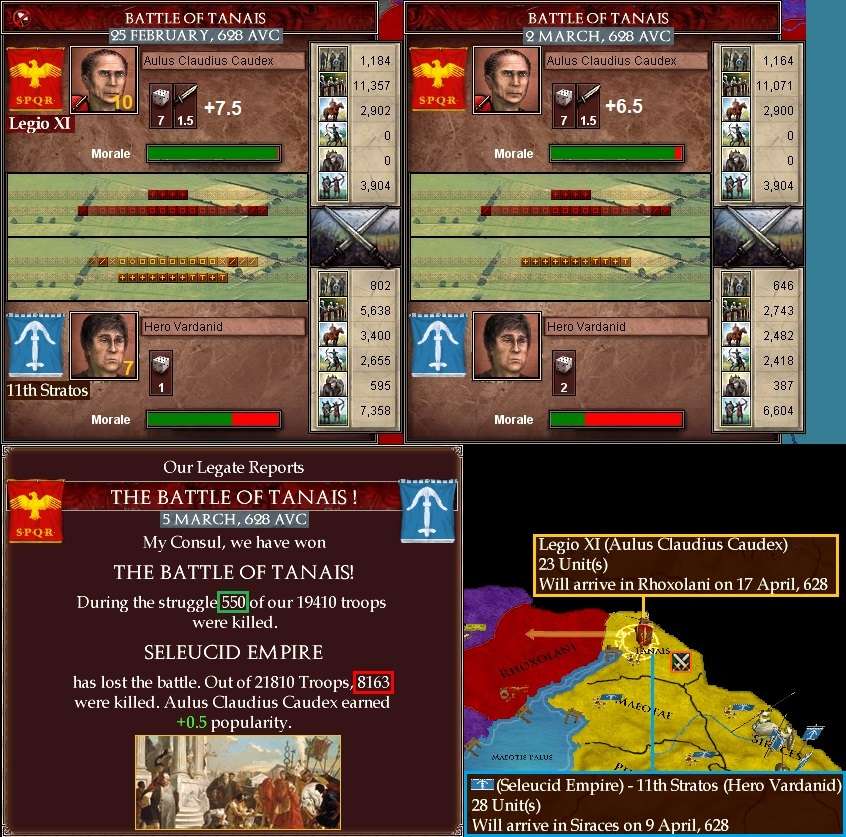

The enemy had a numerical advantage of more than 8,000 troops, but Rome had slightly better leadership and an advantage in heavy infantry and archers. Caudex opened well, inflicting heavy casualties on the attackers.

But when the battlefield position changed on 19 February, he quickly withdrew to claim a ‘moral victory’ before more Roman blood was carelessly spilled. He managed to get away without hazard and would take up the fight in a fall-back position in Alazones.

The Pontic 1st Stratos split off and headed back east to Tanais after their Pyrrhic victory, with only the Seleucid 2nd Stratos chasing Caudex and Maximus to Alazones. Whether this was wise or a dereliction of duty to an ally would be decided in due course.

In Asia Minor, the 12th Stratos had reached Phrygia and would make it to Bithynia by 11 March – just five days before Legio IV could complete its crossing on the 16th. On 2 March, Florus reluctantly ordered a halt: he would not risk a beach assault against roughly equal numbers of Seleucid troops.

The Roman waiting game in Asia Minor would continue. At this time, the Roman Army fielded 275 cohorts, with 37,538 replacements needed and 87,974 men in reserve. And, as will be discussed in more detail in a subsequent section, another diplomatic blow fell on Rome on 3 March: Egypt was the latest country to take advantage of supposed Roman distraction by declaring war! It seemed the whole world was being engulfed in the flames of war.

On 5 March, a fleet of 36 Seleucid ships was discovered in Mare Aegyptiacum, making west for Hermanaeum Promontorum. Rome had no desire to see a sizeable Seleucid fleet cruising around ‘Their Sea’, so Classis IV (86 ships) was despatched from their patrol station in Mare Carpathicum under Naval Prefect S.A. Barbula to intercept them. Another eight repaired galleys were sent out from Rhodes as reinforcements if needed.

Seeing they would be intercepted, the Seleucids changed course on 8 March and tried to head north to safety instead. Barbula gave chase, hoping to catch them in Mare Aegyptiacum before they could slip away. In this he was successful, with a major naval battle erupting on 16 March.

Despite being heavily outclassed on paper as a commander, Barbula managed to keep the upper hand tactically for the first 20 days of the combat, after the Rhodes detachment joined him soon after the battle started. By 10 April, Rome had lost two ships and the Seleucids nine.

Just to complicate things on the northern front, 10,000 rebellious slaves rose in Olbia on 27 March. With none of the legions in the Euxine sector easily spared, the town would have to ensure a long siege while the recovering ‘replacement legion’ in Triballi made its long march north under G.F. Pictor, gathering sundry replacements along the way.

March 629 AUC ended with Classis V in Mare Myrtoum, ordered east to be ready to join the great battle still going in Mare Aegyptiacum at that time.

§§§§§§§

By 11 April, Classiv V was approaching the continuing naval battle line, where both sides were losing ships and neither willing to flee. The well-performed Barbula regained a slight tactical edge on 15 April and the arrival of Classis V on 19 April proved devastating for the enemy: their whole fleet was sunk, for the loss of eight Roman galleys in the decisive naval battle of the current war.

On the land, the next battle in the Euxine campaign began on 26 April. Two days before, Legio XI and VI had pulled into Alazones on the 24th, the whole force being merged into Legio XI under Caudex’s sole command. Meanwhile, Roman sieges of Sarmatia, Taurica and Panticapaeum were all progressing to varying degrees. Helpfully, the Pontic army’s march south had been prompted by a small rebellion against Seleucid rule in Phanagoria.

As it transpired, the numbers were fairly even when the latest battle began in Alazones on 26 April. And the Seleucids had sent in mediocre commander against Rome’s best, with an army carrying more light than heavy infantry – and attacking over a river. The result was quick but not pretty for the enemy. And the value of keeping Caudex happy was once again being proven.

In Olbia, a new cohort was due to finish training soon, but looked doomed to be ambushed by the rebels, with no relief in sight. They were indeed all killed on 7 May, for the cost of only four rebel scum: revenge may be delayed, but it would surely be exacted.

Pontus had rejected Rome’s earlier very reasonable peace offer. This time, they offered one of their own. The Senate was happy, and so too was the outgoing Consul S.A. Barbula (whose term would expire on 25 May, more details in Section 4 below). Peace with Pontus it would be, with the Seleucids and Egypt still to be reckoned with.

It also meant Rome’s holdings in the northern Euxine coast would be continuous. And the war there with the Seleucids would continue. At the time of this deal, Rome’s cohort strength had risen to 293 with recent auxiliary recruiting. Manpower was at 80,040 with 38,196 replacements required.

Following the victory in Alazones, in mid-May Caudex decided to hold in the favourable terrain there, with another Seleucid army on the way – the 8th Stratos. After the peace with Pontus, Legio IX was heading back from Sarmatia and would arrive in Alazones before the enemy could attack.

The relief force for Olbia was in Piephigi by 29 May and Lgio VI was re-establish, and experienced (76-year-old) S.C. Maximus put in charge. After he’d picked up a few more loose cohorts along the way, he would move to relieve Olbia, which still held strongly enough against the rebel siege.

As June drew to a close, Legio IX joined Legio XI in Alazones and awaited the enemy attack, due in early July: given the crowding (64 Roman cohorts and 28 retreating Seleucid units), attrition

[5%] was affecting all troops. Elsewhere, battles were in progress in Egypt and Gaul …

§§§§§§§

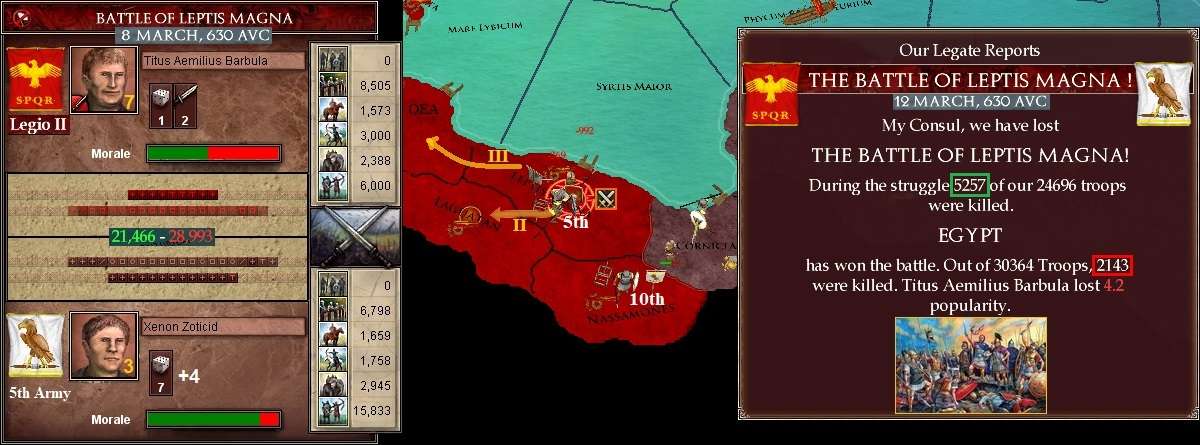

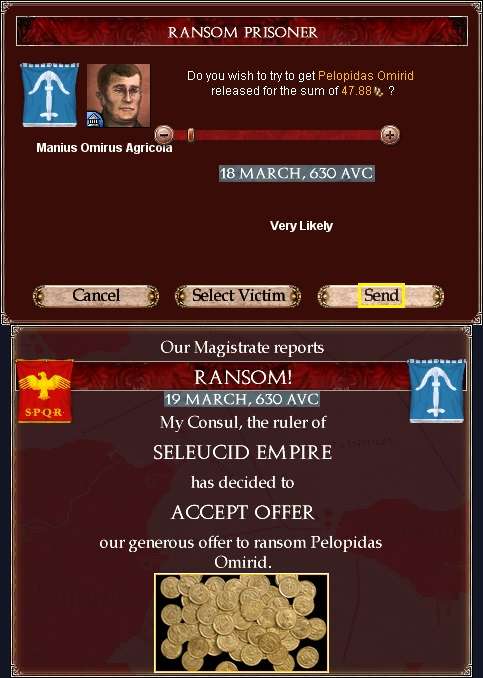

2. Egypt: March 629 to January 630 AUC

As noted, above, it was something of a shock when Egypt declared war on Rome on 3 March 629. But at least a strong force had been kept on the border with Egypt proper. Consul Barbula was so incensed by both the Egyptian envoys message and manner that he broke with all civilised protocol and had the man beheaded. He did not care for the effect on Roman-Egyptian relations, foreign sensibilities (bad-boy points) or domestic opinion (infamy). Humphronius tut-tutted rather censoriously, but Bubulcus would not relent.

Oh, COME ON!

Yet another DoW?

Yet another DoW?

Faithful Massilia responded to Rome’s call to join this latest war, which left Rome up against the next three most powerful realms left in the Known World. Even after more than two years of war, Rome still had plenty of money and a modest manpower reserve. Pontus had little left of anything, but both Egypt and the Seleucids had ample manpower and a significant technological edge over Rome, though the Seleucids were comparatively broke and their government unstable.

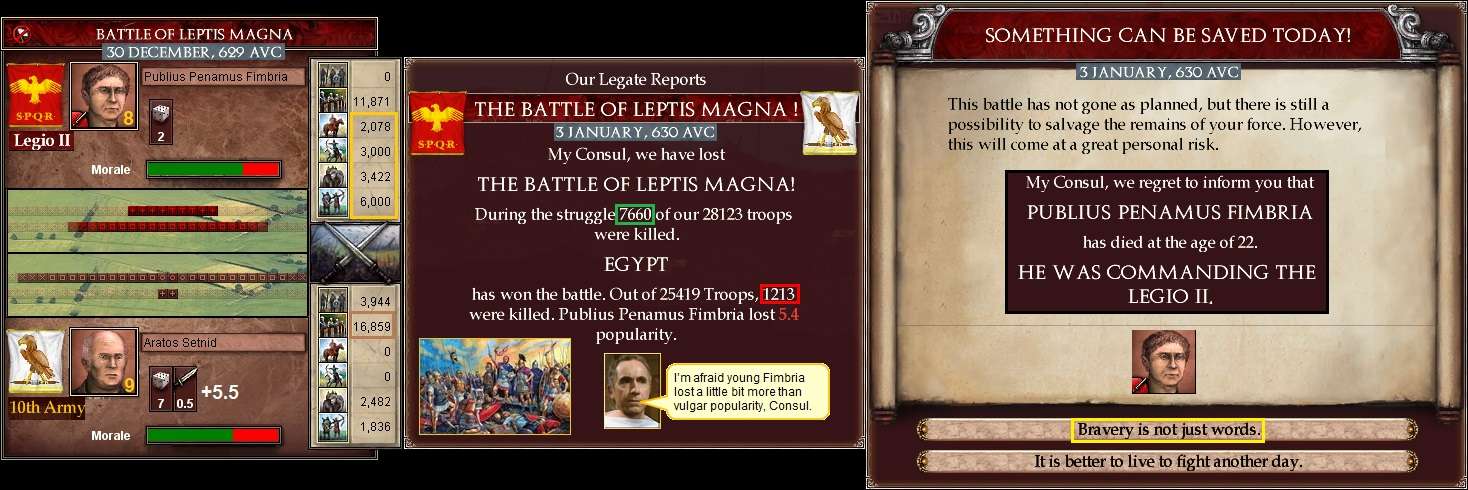

Rome was in no great hurry to launch any aggressive action in Egyptian theatre: prior experience told them it would not be sustainable given the care that needed to be taken with manpower and a war on multiple fronts. One of the S.C. Maximus triumvirate (after a period of exile following the catastrophic loss of Legio I in Lydia) was appointed commander of Legio III, to ensure solid leadership of both legions, with the promising young legate P.P. Fimbria retaining command of Legio II.

The Egyptians however had other ideas and launched into an attack on Nassamones, striking in mid-April. The Egyptians were very strong in heavy infantry, had a better commander and an overall numerical advantage.

But the threat of Legio III reinforcing from the north seemed to scare them off, though Fimbria’s command had been badly bloodied in the short battle.

Things got complicated after this initial encounter. Aratos Setnid’s 10th Army was back in Corniclanum by the end of May. It first moved to return to Nassamones, but a feint from Legio III baulked them. They responded by making for Leptis Magna on 2 June, but that was averted by Legio II feinting there instead.

Setnid returned to his original plan of attacking Nassamones, which he could reach before Fimbria could leave it or Maximus reach it.

Instead of keeping on track to reinforce Fimbria in Nassamones, when battle was joined on 18 June Maximus thought Fimbria could handle it himself made the fateful decision to switch his thrust east again, hoping to cut Setnid off then destroy his army in league with Fimbria, especially if Setnid was defeated and forced to retreat back to Corniclanum.

Things did start well for Fimbria in a close enough battle. But as Setnid gained a slight upper hand on 23 June, the folly of Maximus’ rash play became obvious when the ratio of casualties began going against the Romans. Fimbria had to take the odium associated with defeat to keep his legion intact, withdrawing when the odds worsened on 28 June.

Following this debacle, mutterings about Maximus – already blamed (fairly or not) for the destruction of Legio I – became louder. Graffiti labelling him as “The Black Crow”, “Maximus Deathbringer”, “The Widowmaker” and even the vulgar “An Known Irrumator for Many Years” appeared on the walls of Leptis Magna, largely by night. Though apparently the conjugation of many of these crude epithets left something to be desired, as one centurion found when apprehending a scribbler one night ...

Setnid began an assault on Nassamones on 2 July. Trying to make up for his error – and perhaps to escape the embarrassment of the burgeoning graffiti epidemic in Leptis Magna – Maximus marched Legio III south to relieve it. By 5 July, as Fimbria arrived in Leptis Magna, Setnid abandoned his assault and headed back east again to Corniclanum.

But the Curse of Maximus struck again: he struck the Egyptians in Nassamones on 28 July with 35,000 fresh troops, expecting to crush a fleeing opponent. Only to find they had been reinforced by a fresh army – the 11th – unseen by Roman scouts

[probably as I tried to keep track of multiple fronts at once  ]

] not long after the battle began. It meant he ended up being badly outnumbered, his advantage in foot and horse archers being no match for the enemy’s better tactics, preponderance of heavy infantry and the fresh reinforcements.

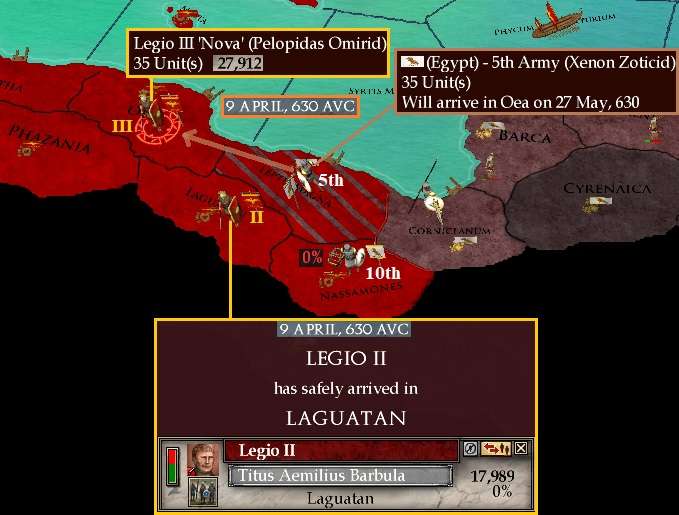

Maximus ‘the Irrumator’ was forced to withdraw after five days, already having taken almost 8,000 casualties. And this time, he took the rap directly. He marched back north in ignominy to Leptis Magna, while Fimbria pulled back to Laguatan both to avoid excessive attrition later and to be in position for a later combined attack on Nassamones. As July ended, Ptolemy Omirid’s 11th Army invested Nassamones while Setnid continued his interrupted march back east.

By the end of August, Legio III was in Leptis Magna (where Maximus tried to avoid the graffiti and sideways looks) and Legio II in Laguatan. An Egyptian assault on Nassamones had just failed, leaving the morale of the 11th Army at rock bottom.

On 2 September, the 10th Army was back in Corniclanum, but now advancing on Leptis Magna, while the 11th stayed in Nassamones. Not wishing to be branded in the same manner as Maximus had, Fimbria immediately set out with Legio II to reinforce Maximus. He was due to arrive 11 days after the Egyptians attacked.

On 7 October, Omirid assaulted the walls of Nassamones again. Setnid was still advancing on Leptis Magna, but then broke that off on 13 October, when the second assault on Nassamones failed. Now coping with some of the same uncertainty his colleague Maximus had, Fimbria decided to switch his march to Nassamones, seeing Maximus seemed safe and the 11th Army was demoralised again. But he prudently sent word to Maximus, who also marched on Nassamones. Both men wanted revenge and redemption.

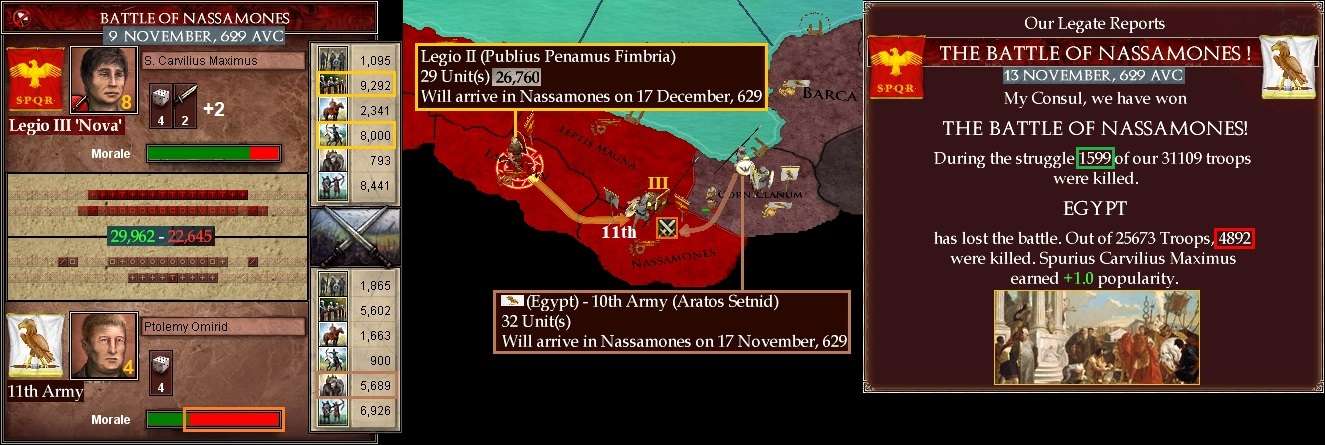

Maximus had the much shorter march and arrived in Nassamones more than a month ahead of Fimbria, on 9 November. Omirid and his 11th Army were not as effective or powerful a foe as the Setnid and the 10th had been. Perhaps the Curse of Maximus had been lifted? A solid Roman victory followed …

… four days before a duly alerted Setnid was due to strike Legio III and a month before Fimbria could reinforce! Maximus started to get that sinking feeling again, but braced for the onslaught.

§§§§§§§

The already complicated Egyptian Front got even more so in the ensuing days. Setnid decided not to attack the recently victorious Maximus in Nassamones. Instead, he struck at the now empty Leptis Magna, which he reached on 2 December. By that time, the 11th Army was back in Corniclanum – and heading further east to Cyrenaica!

On 14 December, Legio II was bearing down now on Leptis Magna, which it should reach on 30 December, with Maximus starting Legio III there too, due to reinforce any battle there on 6 January. In response, Setnid broke his siege and began withdrawing towards Corniclanum, but he would not get away until 13 January. 11th Army had earlier reversed course and also marched for Leptis Magna, which it should reach on 27 December – just before Fimbria’s arrival. Only to decide against it the next day, halting in Corniclanum and leaving his colleague Setnid to his own fate.

Maximus then once again abandoned his colleague, halting in Nassamones on 17 December to forestall an Egyptian reappearance and keep an eye of Omirid. The situation was therefore that the 10th Army still fled towards Corniclanum, but would be caught by Fimbria’s Legio II in Leptis Magna in 30 December.

Once again, the young Fimbria faced off against Setnid, this time with the overall advantage in numbers, strong in the supporting arms, while Setnid maintained his great core of heavy infantry. Alas, the battle got off to a horrible start for Rome and the casualties soon mounted precipitately. Fimbria’s first thought was to preserve the lives of his men from this disaster, once again due to the abandonment of the Great Irrumator. He bravely stayed back to command the rear guard …

… and paid the price always described by historians as the ultimate one. A young career had been cut short in the cruellest way.

When the battle had started so poorly, the guilty Maximus had begun marching north again, but would on 23 January. Too little, too late. Again.

24 January found him languishing in Leptis Magna once more, with even his own staff unable to look him in the eye, mumbling briefly and excusing themselves as soon as they could from the cursed presence of “Fimbria’s Bane”. A small Egyptian detachment of two regiments was heading for Leptis Magna, due in six days’ time. The problem came after them: a new outfit, the 5th Army (Xenon Zoticid, 34 units) was due to hit Leptis Magna on 8 February and the 11th Army (36 units) due in a day after that.

The 10th Army (32 units) should arrive in Nassamones – abandoned by Maximus in his fruitless attempt to make amends for the death of Fimbria.

Catastrophe, thy name is S.C. Maximus! He gave orders to escape to Oea, but it was a long way and he could not arrive there before 19 March. The now leaderless and routing Legio II would make it Laguatan on 31 January: ironically, just in time to

not be there when the latest Egyptian assault arrived.

The two Egyptian regiments were ambushed and destroyed by Legio III on 30 January for no loss. But worse was to come, of course. Meanwhile, Legio II arrived in Laguatan on 31 January and was able to have a new legate appointed: the experienced 41-year-old Titus Aemilius Barbula

[Martial 7]. By 3 February, Setnid was in Nassamones and assaulting its strong walls. The outcome of the impending battle in Leptis Magna will be covered in a subsequent chapter.

§§§§§§§

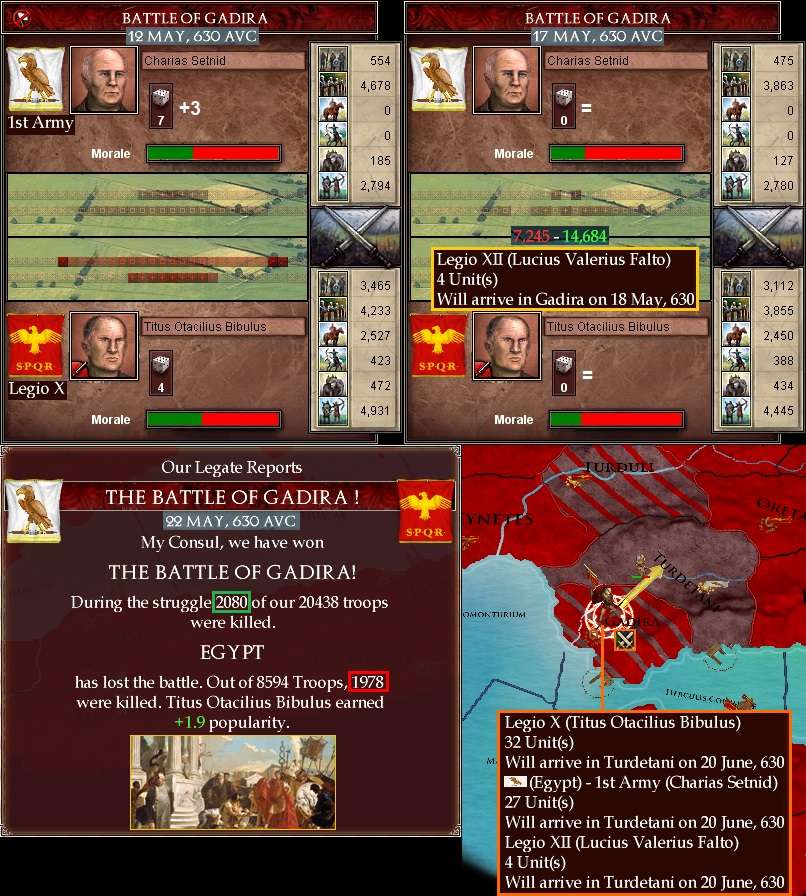

3. Hispania: March 629 to January 630 AUC

A rebellion broke out in Gadira on 1 March 629. But two days later, the 6,000 rebels now looked a minor nuisance by comparison to what would now get be getting up to. On 5 March 629, two days after the Egyptian declaration of war, Legio XII (12,000 men) had been embarked and ready to sail off on a Roman fleet to conduct a naval landing to relieve the city. These plans were now shelved, as a large Egyptian army moved on Gadira from Turdetani.

A new round of recruiting on 8 March saw nine cohorts of

principes, six of

velites (militia) and two of archers go into training across the Republic. Quite a number of these would be raised in Hispania (principally militia and archers), as Legio XII now found itself badly outnumbered.

Legio X, then resting in Aulerci (northern Gaul) was ordered to march all the way to Hispania with its 12,000 men, leaving just one legion in the vicinity to keep the peace internally and along the German border with Gaul. Back on dry land on 12 March, Legio XII headed to Egyptian Turduli to begin a siege while the Egyptians were preoccupied with Gadira.

An Egyptian fleet was spotted in the Pillars of Hercules on 25 March, so Classis VI (S.L. Primus, 31 ships) started out from Lusitani to see if it could intercept them or any other Egyptian ships that might venture out of Turdetani. Two days later, the Egyptian 1st Army (Charias Setnid, 27 units) had defeated the rebels in Gadira and taken over the siege. Scouts reported they had more than 15,000 heavy infantry and 7,000 archers in their force.

Classis VI arrived at the Pillars on 3 May, to discover a single Egyptian galley, which was quickly sunk. The eleven Egyptian ships previously in Turdetani had apparently split up and moved east, but the Massilians had intercepted them in Insulae Pytiussae, where a naval battle was in progress. Primus set out to chase the three Egyptian ships heading there, to see if he could provide Rome’s allies any assistance.

On land, Legio XII was in Vettones

en route to Turduli, while nine recently recruited cohorts had just finished training and were also concentrating there. By 9 May, there were 14 Massilian and 11 Egyptian ships fighting in Insulae Pytiussae: Primus hoped he would not be too late to join the party.

Legio XII had Turduli under siege by 26 May, but its garrison of 3,000 men would not be quickly or easily dislodged.

Primus got his wish, reinforcing the Massilians in Insulae Pytiussae just in time to help sink the last Egyptian ships, with one captured by the Massilian admiral: a job well done.

An Egyptian assault on Gadira

[13% siege progress] failed in early July, leaving more than 2,100 men still manning the walls, with the assault and attrition whittling down Egyptian troop numbers. They would try and fail again to storm the walls in early September, leaving them with only around 19,000 of the 27,000 they had set out with.

By 27 September, a new legion was forming in Oretani, where Titus Otacilius Bibulus

[28 years old, 8 Martial] now had 13,000 men (7,000 militia, 2,000 principes, 1,000 cavalry and 3,000 archers). Another seven cohorts were detached from Legio XII to join him, leaving just four under L.V. Falto to maintain the siege of Turduli.

Legio X arrived in Oretani on 22 November and all the troops there were gathered under its eagle, giving Bibulus around 32,000 men in a mixed force, based around ten light and nine heavy infantry cohorts. He set off to march through Turdetani to attack the Egyptians besieging Gadira.

In early December, no doubt detecting the Roman advance, the Egyptians assaulted Gadira once more, this time prevailing on 8 December. Classis VI stood if in Herculis Columnae, ensuring the enemy could not escape across the strait to Africa.

Bibulus would attack on 7 January 630 AUC, having lost some of his strength to attrition on the march through Turdetani. He found the Egyptians’ morale had not yet recovered, and though the Romans had more than 10,000 troops, Egypt had more heavy infantry. Despite the two generals being evenly matched in skill, Bibulus could never quite get the tactical advantage over his wily opponent.

The eventual ‘victory’ proved hideously expensive, but Legio X would maintain the pursuit around two weeks behind the fleeing Egyptians. The siege in Turduli was progressing well, but Bibulus could not allow the enemy to disrupt it, hence the pursuit rather than assaulting Gadira immediately.

Overall, in the first eleven months of the separate war with Egypt, Roman casualties had been heavy: losses they could ill afford given the many demands on their limited manpower.

§§§§§§§

4. Gaul, Africa and General Events: January to December 629 AUC

January 629 witnessed the final throes of the campaign against the Lexovii in north-western Gaul. T.A. Barbula’s Legio X cornered them in Pictones, winning a battle there between 19-23 January (Rome 509/12,000; Lexovii 1,811/4,811 killed). He pursued them to Aulerci, where the invaders were finally wiped out on 23 February (Rome 58/11,967; Lexovii all 2,800 killed), with 6.4 gold and 11,000 slaves taken. It was from there that Legio X would soon be redeployed to Hispania after war with Egypt broke out.

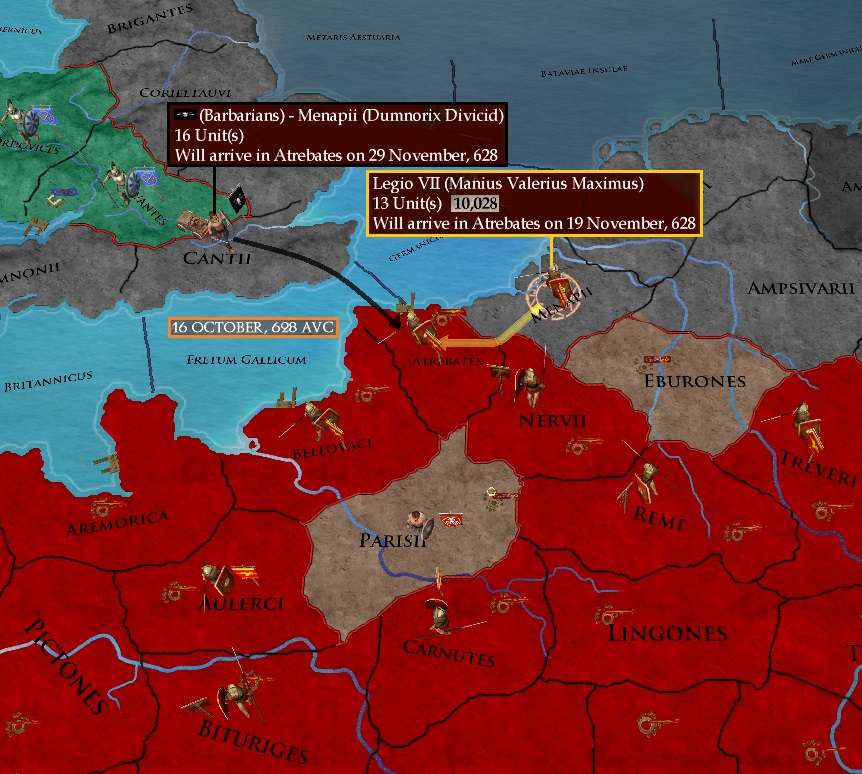

The Menapii were also still active, crossing back over from Britannia to attack Legio VII in Atrebates on 21 March. Defending a beach landing from a wooded position, the Romans soon had the barbarians running away – to their native Menapii (Rome 32/14,333; Menapii 4,470/11,714 killed).

A major trade discovery in April saw the whole Republic get a big economic and productivity boost, with global trade expanded in every province (both extra money and bonus for the exchanged trade goods).

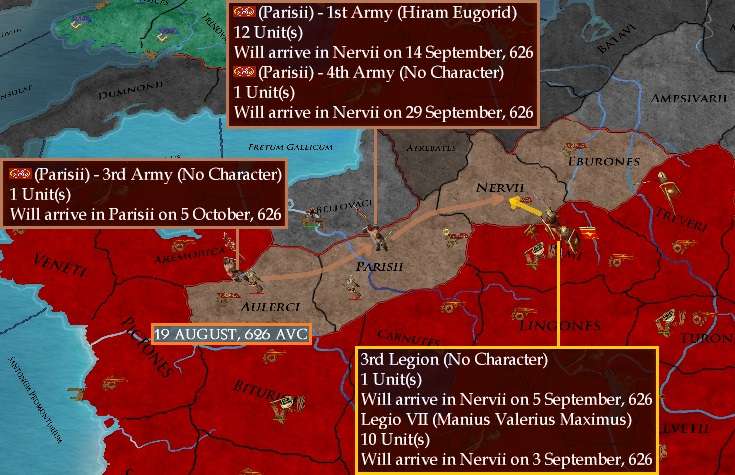

M.V. Maximus (Legio VII) had expected the Menapii to return to Atrebates in the time-honoured barbarian tradition of dashing themselves to death against prepared Roman positions. But instead, too late, on 9 May he realised they were heading to Nervii instead, where a newly trained cohort would be caught before they could escape. He marched towards Nervii, albeit to late to help the new auxiliary cohort there.

Back in Rome, it was election time again. The Religious faction would regain control of the Consulship through Drusus Carvilius Maximus (this family seemed to be everywhere). Though only 45, his health was poor, but the chances of a good omen would be increased.

The incoming Consul report he received from Humphronius and Bernardius included a long catalogue of restive provinces that might revolt. The Consul broke into a coughing fit as he read it and called his officials to fetch his physician immediately.

The two exchanged loaded glances, intoned “Yes, Consul.” In unison they departed, wondering how long this magistrate would last.

Just two days later, the unfortunate cohort of

principes in Nervii was ambushed and wiped out (Rome all 1,000; Menapii 26/7,084 killed). M.V. Maximus, who had rounded up reinforcements along the way, marched on grimly when he was informed of this sad news.

He wouldn’t catch up with the barbarians until 22 June, defeating them in a grim battle by 2 July (Rome 1,075/16,155; Menapii 3,160/7,085 killed). The Menapii fled towards Germania and Maximus waited to see if they would come back this time.

§§§§§§§

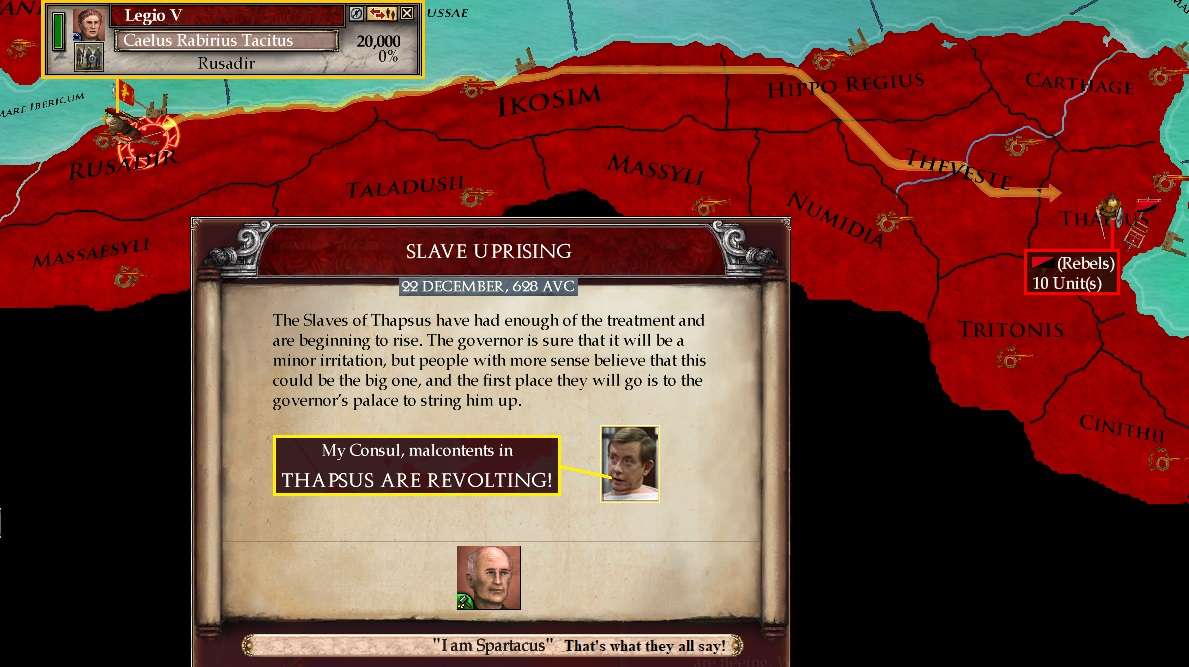

Thapsus, which had revolted some months before, was starting to weaken when C.R. Tacitus finally showed up with Legio V on 22 July. A bloody battle ensued, but fortunately the lack of ability Tacitus demonstrated was more than compensated for by his superior numbers of better troops.

As soon as the job was done, his legion started marching all the way back to where they had come from.

In Gaul, the Mebapii did foolishly return to Nervii for a final showdown from 31 August to 5 September. It ended in a massacre (Rome 0/16,095; Menapii all 3,578 killed), with a little gold and 12,000 slaves taken. With that, the Menapii Invasion was over.

A new advance in military technology was made in November 629, with possible benefits for Rome’s cavalry troops hoped for down the track.

Consul Maximus, who had at least survived the first six months of his term, oversaw a successful omen in early December.

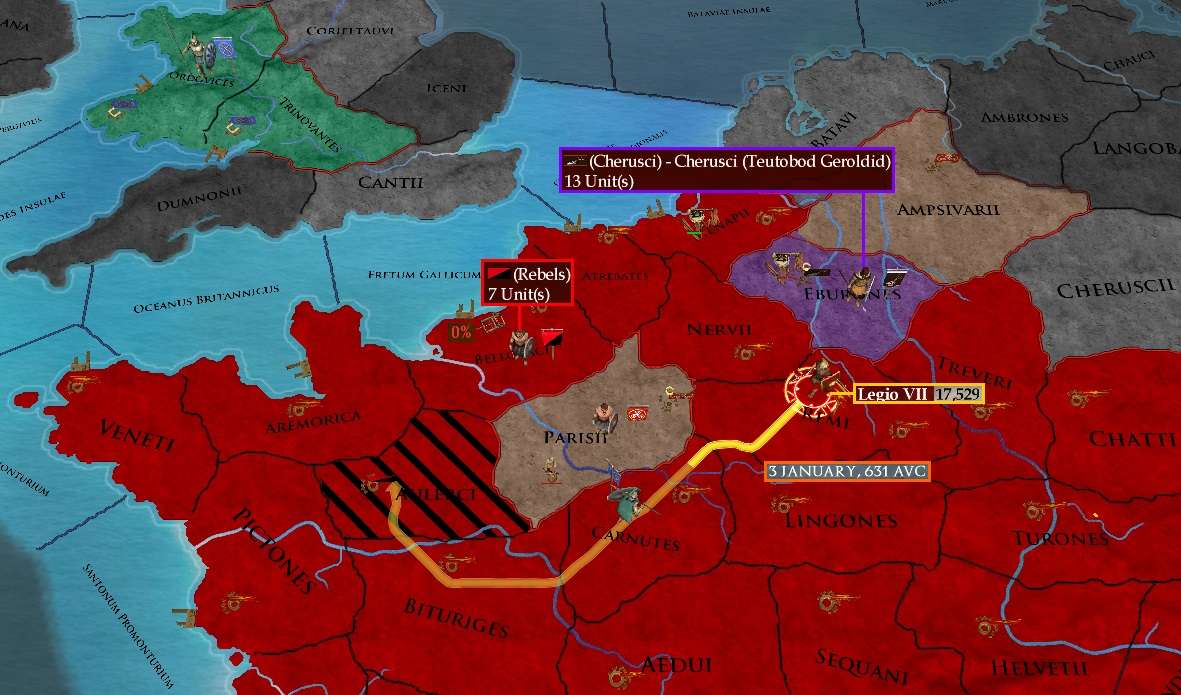

The year ended with mixed news in northern Gaul. Menapii became available for colonisation and settlers were despatched on 14 December. But at the same time, a large warband of around 16,000 Cherusci appeared in Ampsivari, heading for Parisian owned Eburones, which they would reach on 25 December. Maximus readied Legio VII in Nervii to respond to any subsequent incursion into Roman territory, but none would occur before January 630.

§§§§§§§

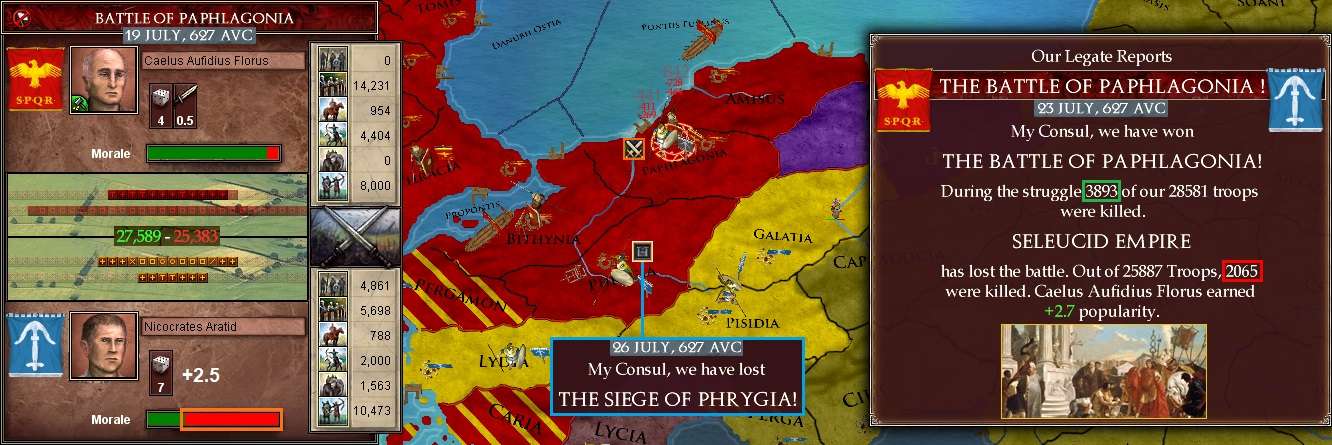

5. The East: July 629 to February 630 AUC

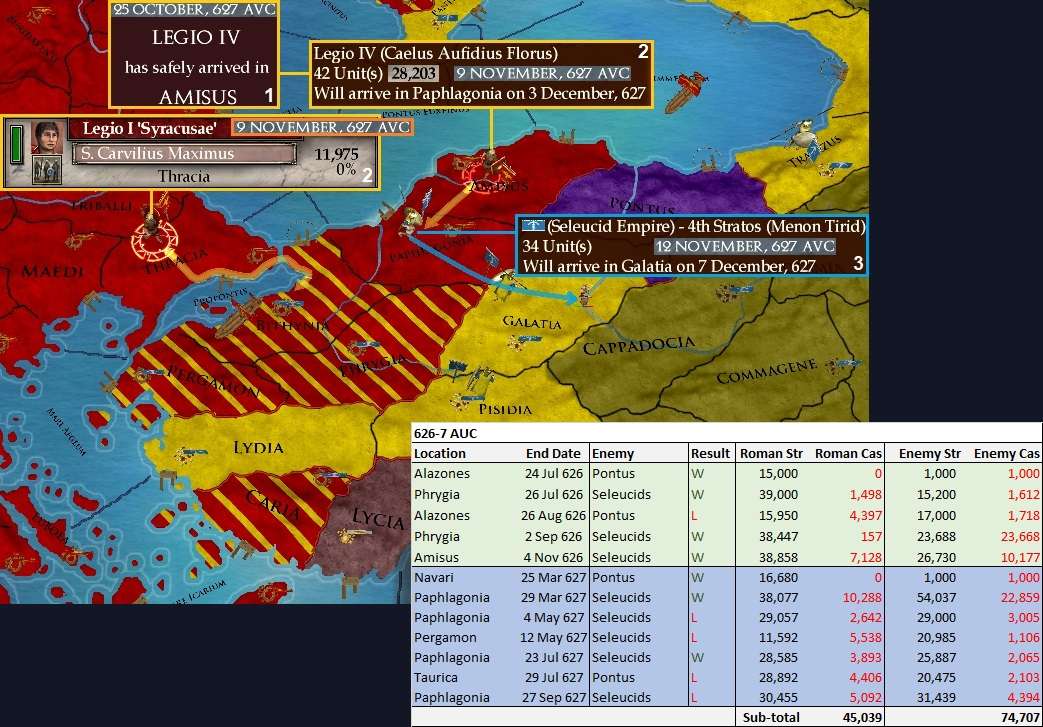

For now, the main action in the east remained on the Euxine front, with Pontus having been peeled away from the conflict. The fresh 8th Stratos, ably enough led by a new Seleucid general in that theatre named Damasias Odroid, attacked Alazones on 17 July in a short but bloody battle. In five days, the effusion of life’s blood was prodigious: of the almost 75,000 troops engaged on both sides, well over 12,000 would die.

A tactically roughly even battle went Rome’s way, their overall numerical advantage with the recent arrival of Legio IX and a significant superiority in heavy infantry saw a significant victory won by Caudex.

A week or so later, the renewed Legio VI (now with over 21,000 men in 25 cohorts), with the eldest and apparently un-cursed S.C. Maximus in charge, was in Iazyges and finally ready to march on Olbia on its way to the main front on the north Euxine shore.

By mid-August, the fighting on multiple fronts had eaten further into manpower reserves, with 69,921 recruits available but 50,833 replacements needed. The point was approaching where a net deficit would occur.

With Rome’s Asia Minor territory still entirely in Seleucid hands, Florus again set out for the ‘long crossing’ of the Propontis (avoiding punishing attrition) to Bithynia from Thracia on 28 August with 41 almost full-strength cohorts. The nearest Seleucid army was in its habitual station in Pisidia.

The main Seleucid strength remained in the north. On 10 September, their 2nd and 5th Stratos were heading to attack Alazones from Rhoxolani in early November, even as the 8th was still retreating from its recent defeat there. On 17 September, all Roman units in Alazones were consolidated under Legio IX, under Caudex’s command. The 43,141 men were consolidated down from 64 to 49 cohorts as continued overcrowding exerted attrition

[5%/month].

Maximus attacked Olbia on 20 September, defeating and dispersing the rebels in a six day battle (Rome 621/23,319; Rebels 3,327/10,000 killed). He then kept marching east, aiming to arrive in Alazones on 28 October, some days before the latest Seleucid horde was due to arrive. By the 28 September, 8th Stratos was back in Rhoxolani – and immediately turned back around to return to Alazones by early December: over 100 Seleucid regiments were now bearing down on the key and now Roman province.

Following the recent consolidation in Alazones, at the start of October 629, the Roman reserve stood at 59,603 with just 24,206 replacements needed, but the total army cohort strength had been reduced back down to 277.

In mid-October, a Seleucid emissary arrived bearing a peace proposal: Rome was willing to bargain, but only on what they considered ‘fair’ terms. The Seleucid offer was punitive, and while a majority of the ‘snivelling toadies and defeatists’ of the Senate were willing to accept it, Consul Maximus was not.

“I may be sick in body, but not in mind,” the Consul responded. “Their offer is declined. Out counter-offer is a white peace.”

“Yes, Consul,” replied a dubious Humphronius – who privately would have qualified as one of those ‘defeatist toadies’ the Consul had scornfully referred to.

The Roman counter-offer was similarly unacceptable to the Seleucids.

“Clearly, we need to reclaim more territory to improve our bargaining position with these Eastern Degenerates,” observed a vexed Maximus. “Order Florus and Caudex to redouble their efforts!”

“Yes, Consul,” sighed a war-weary Humphronius. It was just bad for business.

Will these glory-seeking strutting peacocks never learn, he thought to himself even as a simpering and unctuous smile was plastered over his insincere visage. He left to relay the orders for Bernardius to write up.

But the Roman generals obliged the will of their Consul. Taurica fell to a long siege and was reclaimed on 23 October. All units in the region now seemed to be converging on Alazones for a climactic battle.

Meanwhile, Legio IV had reached Bithynia unhindered the day before and wasted no time in an assault that cost around 550 troops but had secured the effective regional capital of Roman Asia Minor by the 25th.

§§§§§§§

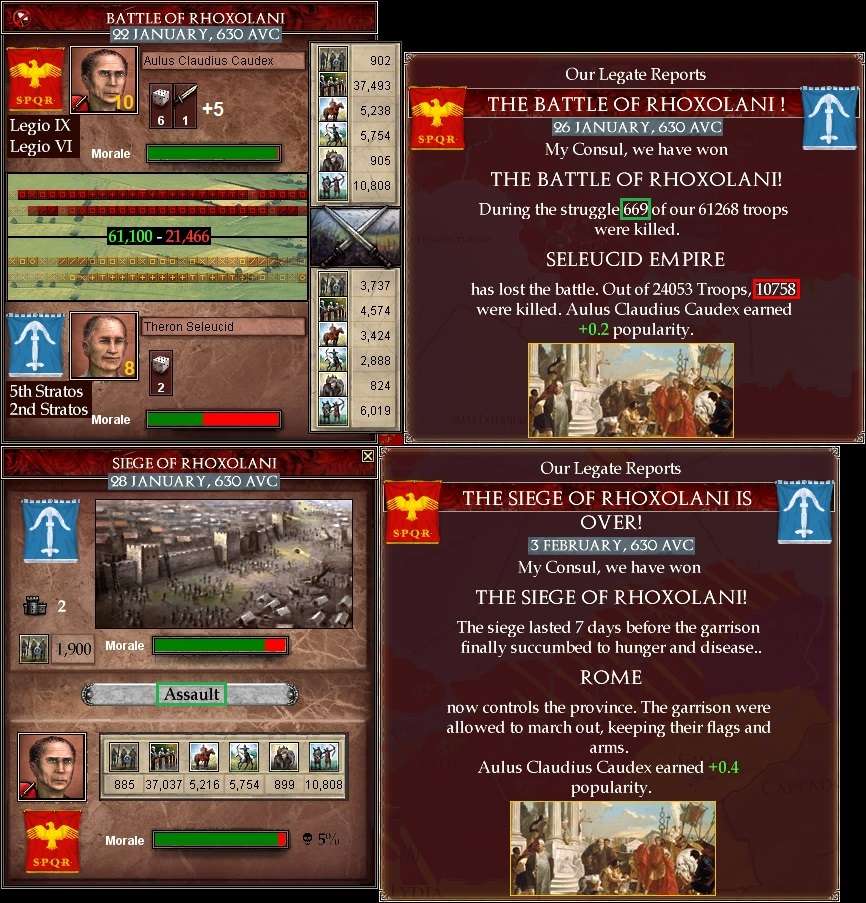

The Seleucids attacked the massed lines of Legio VI and IX in Alazones on the morning of 7 November 629 AUC, in one of the greatest battles of the period, with over 117,000 soldiers contesting the field. Caudex had found a wooded hill overlooking a river to defend and the Seleucids obliged by attacking. Disastrously, for them.

The combination of the ground and Caudex’s superior skills and a core of over 41,000

principes were too much for the enemy, who lost over 20,000 killed in just six days before beating a hasty retreat. By comparison, Roman casualties were light. Caudex was more popular than ever and most felt the many past payments had by now been fully repaid in glory and victory.

A ‘repair column’ of the ten most damaged cohorts (4,475 men) was sent back to recover in Olbia on 14 November as Caudex and Maximus the Elder contemplated their next move. Which would be an advance on Rhoxolani, where the 8th Stratos had now halted, to retain the momentum of the recent colossal victory. But before that, Caudex’s loyalty had to once again be guaranteed: this time with a great triumph none could object to, under the circumstances.

But even as he received the plaudits, Caudex, now aged 61, still had thoughts for his lost love Padmé Amidala Ptolemy, dead so many years before in Alexandria.

Down in Asia Minor, Florus had advanced unopposed to Phrygia on 22 November, assaulting the 1,800 man Seleucid garrison and gaining the walls after a week of fighting in which he lost around 640 men. No Seleucid armies looked to intervene: the nearest visible, the 4th Stratos in Pontus (21 units), was seen heading east to Trapezus. It was assumed they were reacting to their heavy loss in the north and headed for that theatre. Had they tangled with Florus, he would almost certainly have trounced them anyway.

As November ended, the army cohort establishment remained at 277, the manpower reserve was 54,567 with 27,122 replacements required. The enforcement of an ‘honourable peace’ with the Seleucids would continue to be prosecuted with full vigour.

More good news came with the fall of Seleucid Panticapaeum to Rome on 8 December after 463 days of siege – the same that had brought word of the fall of Gadira to Egypt in the West. By mid-month, Legio IV was in Paphlagonia, but troop morale needed to recover somewhat before an assault on the 1,600 man garrison could be safely contemplated. A week later, more auxiliary recruiting was initiated, with six

velites and four

principes cohorts put into training.

§§§§§§§

The first major action of 630 AUC was in Rhoxolani, where Caudex and Maximus led a vicious attack on the battered remnants of the 2nd and 5th Seleucid Armies – the 8th had (perhaps wisely for them) fled before the Romans arrived. Outnumbered almost three-to-one and decisively out-generalled, it was another disaster for the harried Seleucids.

Wasting no time, Caudex soon followed up with an assault on the walls of the town, where the garrison was overcome after a week of fighting.

But the constant combat and attrition of wider war, especially in Egypt, was taking its toll: by 30 January, the Roman reserve was down to 45,251 with 41,040 replacements being demanded. Peace with the Seleucids at the least was badly needed.

Florus obliged again on 3 February, when his now ready Legio IV stormed the walls of Paphlagonia, gaining them three days later.

This had put Rome in a better position to bargain, making a peace offer that very day, giving no territorial concessions but handing over 150 gold talents to return to the

status quo ante bellum between the two great powers.

The offer was accepted the next day. The last year had seen the enemy take some horrendous casualties at relatively light Roman cost, while much territory had been regained to enable a face-saving peace for both sides. Since the war had started back in July 626 AUC, Pontus and the Seleucids had suffered a total of almost twice the combat casualties of their Roman counterparts (and probably more attrition too), thanks to a careful defensive campaign and the adroit leadership of Caudex and Florus.

The war with the Seleucids was finally over. Now something would have to be done about Egypt. Rome wanted peace there too, but would dearly love to eliminate the final Egyptian colonies in Hispania. Whether this could be achieved without excessive sanguinary effusion remained a moot point.

§§§§§§§

Finis