In the Age of Superpowers: 1914 - 1964

-----

As far as assassination plots go, the attack upon the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne Franz Ferdinand would have gone down as one of the most farcical intrigues in history, if only it had not been successful. On June 28, 1914, a band of Serbian nationalists armed with pistols and time bombs took their positions in the streets of Sarajevo. As the touring Habsburg prince's motorcade passed by, the first two would-be assassins had second thoughts and failed to act. A third, lobbing an explosive, missed and managed only to disable a nearby car and wound several bystanders, before stumbling into a five-inch deep river and taking a cyanide capsule that only managed to induce vomiting. An angry mob severely beat the assassin before police arrested him.

The attempt on Franz Ferdinand's life did not especially perturb the Austrian prince, and the tour of Sarajevo continued as planned. After an angry outburst at the town hall and a few brief references to the incident in a prepared speech, the event seemed to leave Ferdinand's mind. But, still fearing for his safety, the security detail decided to take an alternate route and avoid the city center. The driver of Ferdinand's car was not informed and took a wrong turn. Quickly realizing his mistake, the driver began to back up, but the car stalled in front of a cafe where one of the conspirators, Gavrilo Princip, had gone to lunch after the initial failed bombing. Drawing his pistol, Princip fired two shots. The Archduke and his wife were dead.

The assassination was greeted with almost uniform condemnation from the governments of Europe. Many wondered if the tottering Habsburg empire might grasp upon the murder as a pretext to invade Serbia and continue its conquest of the Balkans. But the Austrians were slow to act and rumors of war faded. At least, until July 25, when Serbia was presented an ultimatum, threatening war if a series of punitive demands were not met within 48 hours. Austria-Hungary had already received assurances that Germany would honor its alliance obligations, and Serbia would soon received similar assurances from its ally Russia. Europe was now on a collision course. Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, Russia began to mobilize. Germany mobilized in response, and France in response to that.

The series of events leading up to the outbreak of war had their origins in the previous forty years. Since 1870, Europe had experienced an unprecedented period without a major war which saw the continent ascend to new heights of power and influence over the rest of the globe. But it was a continent still divided against itself, divided by burning class struggles and national ambitions. The Great Powers maneuvered constantly for advantages, forming strategic alliances, grabbing up colonies thousands of miles away in distant lands, all while raising massive armies ready to march on a moment's notice.

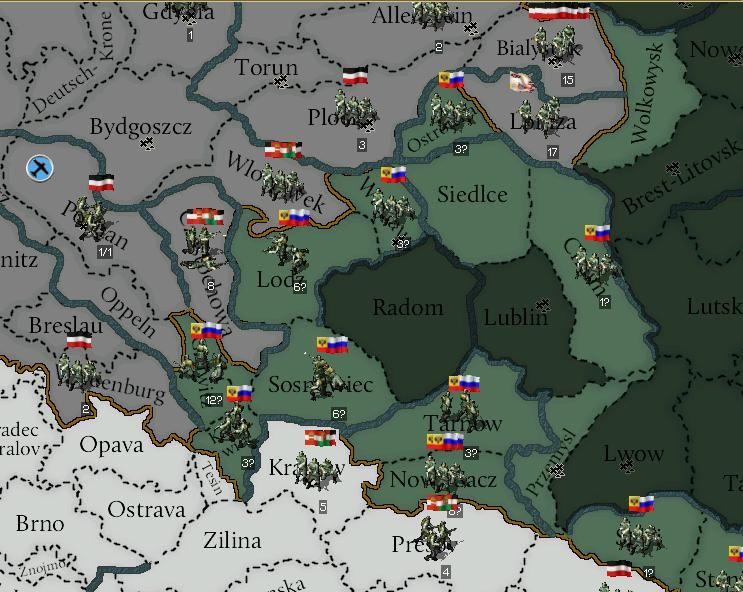

Now, the slide towards war seemed unavoidable, like a massive train barreling toward calamity. Mobilization by one nation necessitated mobilization by all the rest, or risk being caught unprepared by an attack. Germany, paranoid and insecure about its position between the two enemies France and Russia, had for years planned on a truly massive strike to the west that would knock France out of the war before Russia could bring its massive numbers to bear, the Schlieffen Plan. Thus, in a rather apt demonstration of the bizarre nature of events of 1914, Germany would direct the vast majority of its armed strength against France in order to protect Austria-Hungary from Russia, and it would do so by invading the tiny states of Belgium and Luxembourg.

In the early morning hours of August 2, 1914, Germany declared war on France. German troops poured across the frontier into Belgium. The long peace was finally over. The Great War had begun. By the end, it would shake the world to its very foundations. It was the end of the Age of the Great Powers, and the beginning of the Age of the Superpowers.

-----

As far as assassination plots go, the attack upon the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne Franz Ferdinand would have gone down as one of the most farcical intrigues in history, if only it had not been successful. On June 28, 1914, a band of Serbian nationalists armed with pistols and time bombs took their positions in the streets of Sarajevo. As the touring Habsburg prince's motorcade passed by, the first two would-be assassins had second thoughts and failed to act. A third, lobbing an explosive, missed and managed only to disable a nearby car and wound several bystanders, before stumbling into a five-inch deep river and taking a cyanide capsule that only managed to induce vomiting. An angry mob severely beat the assassin before police arrested him.

The attempt on Franz Ferdinand's life did not especially perturb the Austrian prince, and the tour of Sarajevo continued as planned. After an angry outburst at the town hall and a few brief references to the incident in a prepared speech, the event seemed to leave Ferdinand's mind. But, still fearing for his safety, the security detail decided to take an alternate route and avoid the city center. The driver of Ferdinand's car was not informed and took a wrong turn. Quickly realizing his mistake, the driver began to back up, but the car stalled in front of a cafe where one of the conspirators, Gavrilo Princip, had gone to lunch after the initial failed bombing. Drawing his pistol, Princip fired two shots. The Archduke and his wife were dead.

The assassination was greeted with almost uniform condemnation from the governments of Europe. Many wondered if the tottering Habsburg empire might grasp upon the murder as a pretext to invade Serbia and continue its conquest of the Balkans. But the Austrians were slow to act and rumors of war faded. At least, until July 25, when Serbia was presented an ultimatum, threatening war if a series of punitive demands were not met within 48 hours. Austria-Hungary had already received assurances that Germany would honor its alliance obligations, and Serbia would soon received similar assurances from its ally Russia. Europe was now on a collision course. Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, Russia began to mobilize. Germany mobilized in response, and France in response to that.

The series of events leading up to the outbreak of war had their origins in the previous forty years. Since 1870, Europe had experienced an unprecedented period without a major war which saw the continent ascend to new heights of power and influence over the rest of the globe. But it was a continent still divided against itself, divided by burning class struggles and national ambitions. The Great Powers maneuvered constantly for advantages, forming strategic alliances, grabbing up colonies thousands of miles away in distant lands, all while raising massive armies ready to march on a moment's notice.

Now, the slide towards war seemed unavoidable, like a massive train barreling toward calamity. Mobilization by one nation necessitated mobilization by all the rest, or risk being caught unprepared by an attack. Germany, paranoid and insecure about its position between the two enemies France and Russia, had for years planned on a truly massive strike to the west that would knock France out of the war before Russia could bring its massive numbers to bear, the Schlieffen Plan. Thus, in a rather apt demonstration of the bizarre nature of events of 1914, Germany would direct the vast majority of its armed strength against France in order to protect Austria-Hungary from Russia, and it would do so by invading the tiny states of Belgium and Luxembourg.

In the early morning hours of August 2, 1914, Germany declared war on France. German troops poured across the frontier into Belgium. The long peace was finally over. The Great War had begun. By the end, it would shake the world to its very foundations. It was the end of the Age of the Great Powers, and the beginning of the Age of the Superpowers.

Last edited: