King Konstantinos - 1913-1915

Konstantinos, the eldest son of Georgios Megos ("the Great," as more nationalist Greeks refered to him), bore an illustrious name. Konstantinos Megos was considered a hero of the Orthodox Church, and founder of the Eastern Roman Empire, yet Konstantinos son of Georgios was to prove an utter disappointment.

At the end of June, 1914, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne was assassinated, and for the next month the world held its breath, as the various alliances of Europe began to creak into action. Outside of Serbia, initially the Balkans were left out of the machinations, but it wasn't long before events took a path of their own, and Greece's charismatic prime minister, Eleftherios Venizelos, came into his own.

By September of 1914 the major powers were embroiled in a ferocious struggle for domination - Germany and Austria-Hungary on one side, and France, Great Britain and Russia on the other. Germany pulled a diplomatic coup in October of 1914 - her gift of the battlecruiser Goeben along with extensive promises of technical support encouraged the Turks to side with Germany and declare war on the Entente. Germany's diplomatic feelers also reached down to Bulgaria, offering them tracts of Serbian land if they assisted Austria-Hungary. By February of 1915, when Italy joined the war on the side of the Entente, officially every major power in Europe was embroiled in the vast conflagration.

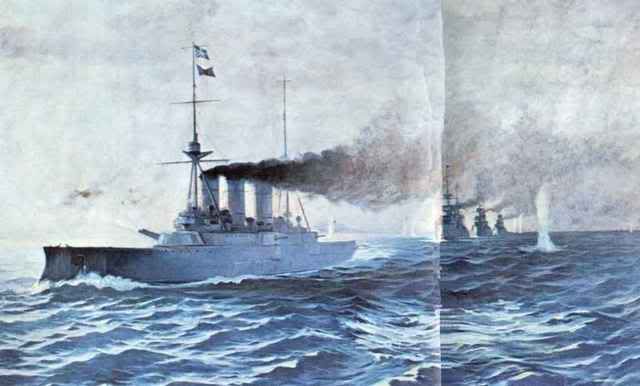

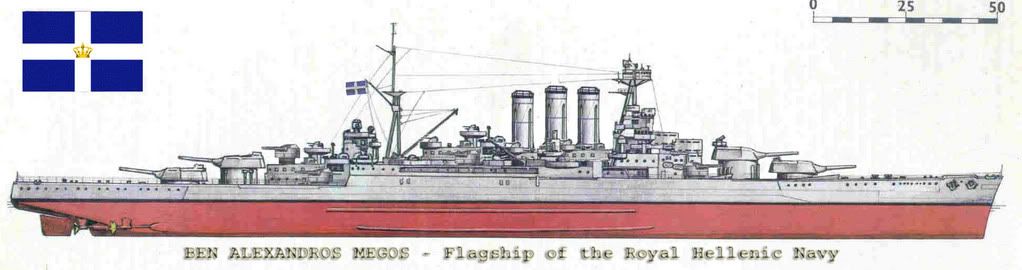

Almost immediately the Greek public clamored for joining the war on the side of the Entente - the plight of Belgium, caught in the crosshairs of a German juggernaught, sympathy for Greece's historic ally Russia as well as hatred for Turkey all fueled these flames. Greece had the manpower (over 400,000 soldiers), and the navy (2 dreadnoughts, 8 other battleships and a battlecruiser, as well as other lighter ships) to contribute significantly. Immediately the Entente recognized their opportunity, and incredible pressure came down on the Greek government to break her neutrality.

To his credit, King Konstantinos remained true to his own convictions - that entering a power struggle between the greatest nations the world had ever known would only result in incredible danger for Greece. At least, that was his official opinion. Many in private wondered if Konstantinos' wife, Sophia (sister to German Kaisar Wilhelm II) was excerting an undo amount of influence on his decision-making. The situation was further complicated by the rivalry between Konstantinos and his own prime minister, the popular and warlike Eleftherios Venizelos.

Venizelos, like most in Greece, saw the Great War was a brilliant, once in a century chance for Greece to realize the entirety of the Megali Idea. Turkey was occupied fighting for her life in the Caucasus, and all of her European troops were tied fighting an Entente invasion in the Dardanelles (indeed, the Entente was holding on on the Gallipoli peninsula in the hopes of Greek intervention). Venizelos argued that now, not later, was the time for Greece to strike - her contribution would be easy, he argued, for all her enemies had their backs turned, and her contribution would be seen as decisive, so her actions would be amply rewarded.

Konstantinos refused to hear this advice, and on May 15th, 1915, Venizelos resigned, bringing down the entire government. Snap elections were called, in which Venizelos won a massive, overwhelming majority. Yet Konstantinos refused to budge, and on August 19th of the same year, Venizelos resigned again - yet this time, he had other plans. Konstantinos' eldest son, Georgios, was known to have similar feelings as his father (as well as having served in the German army prior to the war), but Alexandros, the second royal son, was a pronounced supporter of the Megali Idea. A playboy, known for his car racing exploits and cardgames than his acumen, Venizelos assumed that then 22-year old Alexandros would be easy to control. He could not have been further from the truth.

The two met secretly at Akrotiri on the island of Thera in September of 1915, and planned a full coup. Greece's military wanted the war, Greece's people wanted the war, the Entente wanted the war, all that was needed was for Venizelos and Alexandros to push things slightly.

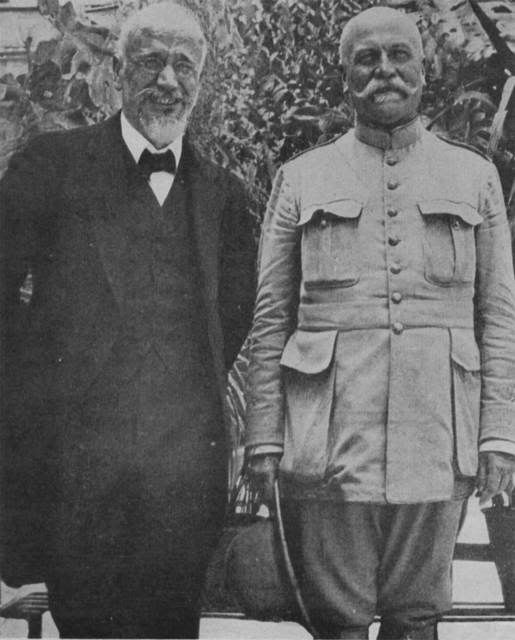

On October 7th, 1915, Venizelos, in coordination with with General Sarrail, Allied commander in the Balkans and several leading Greek military commanders (including Admiral Koutouriotis and General Papagos) declared Konstantinos a violator of the Greek constitution, and an enemy of free Hellenes. Venizelos called for a vote in the Greek Parliament to confirm their support for Alexandros as the new King. Simultaneous, Koutouriotis positioned the dreadnoughts Lemnos and Elli in position to bombard the palace, while Papagos ordered army troops to surround Konstantinos and his entourage.

Army troops in the streets of Athens during the 1915 coup against Konstantinos

At first, it appeared Konstantinos would resist, and several loyal companies of the Royal Companions seemed ready to lay down their lives in the coming bloodshed. But the appearance of Alexandros, on horseback in full military regalia outside of the palace gates in support of the plotters, broke Konstantinos' will. Seeing the inevitable, Konstantinos abdicated. The very next day Alexandros was proclaimed King of the Hellenes, and within hours, to great fanfare, Greece declared war on the Central Powers.

Konstantinos had originally planned to go into exile and await what he hoped would be an Entente defeat, whereby Germany would then forcibly reinstate him to his throne. But as the war went on his bloody course, this chance turned into something far more fleeting. While Georgios was allowed to return later on to the country, Konstantinos, for the rest of his natural life, was banned from walking on Greek soil. He died in exile in Zurich in 1924.

Alexandros I 1915-

Part One

Part One

Alexandros' reign, like that of his namesake, began immediately with war. At 22, Alexandros had a basic military education (as was required by all the sons of the King), but his main interests lay in fast cars and loose women. Yet once the royal crown was on his head, he set about his new duties with a passion and enthusiasm that surprised and dismayed all those around him, especially Venizelos.

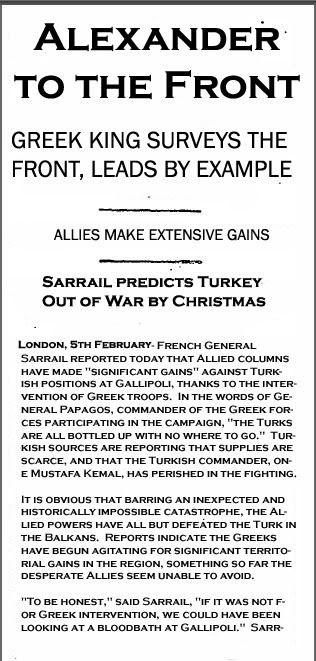

Papagos had pre-positioned several corps on the Macedonian and Thracian borders, and some 250,000 Greek troops on December 10th, 1915 lurched into combat. Quickly some 100,000 troops, named the Army of Thrace, along with 50,000 French, marched towards the Dardanelles under the command of Papagos and the King, who insisted he go with his troops and lead by example.

Another 50,000 Greek soldiers moved into Macedonia and then Serbian, stiffening a badly battered Serbian line in the face of an Austrian onslaught. A further 100,000, labelled the Army of the Danube, marched into an undefended Bulgaria, quickly occupying the nation. By January of 1916, Bulgaria had already been knocked from the war, while 180,000 Turks under Mustafa Kemal were suddenly surrounded on the Gallipoli peninsula. Cut off from all aid, under Entente naval bombardment and pressure

from land and sea, on April 1st, 1916 Otto von Sanders, German military adviser to the Turkish Army of Constantinople, was forced to offer surrender terms to the Allies - Kemal having been killed in a bombardment by Greek artillery.

Alexandros was at the forefront of the action throughout, at points his enthusiasm getting the best of him. Veterans tell the tale that during a particularly fierce Turkish artillery barrage, that the King was founding on a parapet, binoculars in hand. Several soldiers dragged him down and into cover. When they asked him why he'd so foolishly expose himself, the King merely shrugged and said he wanted a clear look. He constantly toured the Greek lines, learning, encouraging, and rapidly becoming extremely popular in his own right.

For Alexandros was not as naive as he first appeared. True, he was wet behind the ears when it came to military affairs - but he was born with a brilliant instinct towards the popular and the flamboyant. His seemingly reckless actions were calculated political manuevers. Each exposure to enemy fire appeared in Greek and Entente press, a King serving alongside his subjects, exposing himself to the same risks. Heroic pictures soon covered the world's press, and Alexandros gained himself an enthusiastic following among Greeks and non-Greeks alike.

A press clipping from the New York Times from this time period.

By this point the remainder of the Greek armies were moving north, another 100,000 to reinforce Serbia, and 50,000 to Thrace. After some reorganization, some 130,000 Greeks, along with 180,000 Entente troops, jointly marched on Constantinople. As Alexandros was the only monarch present, protocol demanded he be given official command, even if Generals Papagos and Sarrail exercised joint authority in reality. Her armies in retreat, the Turks were unable to marshal an effective resistance.

Citizen-brigades set up barricades and proudly proclaimed that they would resist to the last man, yet in the face of a true army most brave citizens melted away without firing a shot. After a brief siege and a few pitched battles, the Allies occupied Constantinople on the 19th of July, 1916. Alexandros rode into the Queen of Cities, and Turkey was knocked from the war, her fate to be decided by other powers.

This boon came just in time, for in February of 1917, the Russian Tsar was overthrown, and Russian contribution to the war effort slacked off, and then petered out altogether. German troops moved into the Balkans to back up their weary Austrian comrades, and the joint Allied front settled in Romania and Serbia. Greece also moved into Albania, citing the "lawlessness" in the region as pretext for setting themselves up as "overseers of the political process."

While the rest of the Great War dragged on, Greece and the Balkan allies hungrily divided up the spoils. Greece, as Venizelos predicted, recieved suzerainty over Albania and Bulgaria, and was able to place heavy demands on Turkey, taking western Anatolia. When Turkish nationalists resisted and tried to raise an army in Ankyra, a force of 80,000 Greeks crushed the revolt and then placed even more onerous terms - Turkey would now cede Constantinople, all her EUropean possessions, as well as all her coastal positions and the Turkish battlefleet. Powerless, the Turkish National Assembly in Ankyra aceded to the demands in the Treaty of Ankyra on November 8th, 1917 - the same day a group of radical communists led by Lenin overthrew the Provisional Government in Russia and proclaimed the Soviet Union of Socialist Republics.

Germany's master plan to end the war - hold the Balkan line and knock France from the war with a sledgehammer victory in the West faltered in the Spring of 1918, and the intervention of the United States finally cracked the four year stalemate that was the Western Front. On November 11th, 1918, Germany surrendered, and the greatest war humanity had ever known came to an abrupt, silent end.

Yet things were just beginning to get interesting for Greece...

A map showing the growth of Greece from 1832-1922. Greek gains after 1872 were extensive and immensely influential on the future course of the nation.