MOZART: THE LATER YEARS 1791-1803 Part 1

Written by Gary Smith, taken from www.mozartforum.com

----------------------

INTRODUCTION

There has always been the discussion that starts out in some fashion: What would have happened with Mozart, had he lived longer? In most cases, this becomes just idle speculation that he would have composed more symphonies or piano concerti, assuredly met Beethoven, become a full-fledged Romantic composer, and so forth. But this all happens against what backdrop? What might be the other circumstances that would cause some, all or none of these milestones to be achieved?

Who's to say? Well, in this case, it might as well be me. While, as it is said, prediction is an uncertain thing, especially about the future, things can occur to force ones' hands. In this case, when one gets an illuminating flash and sees a timeline and events suddenly present themselves, uncalled for but presented very clearly, then one is impelled to record the information for discussion, if nothing else.

So, I offer this work, the fruits of a long and laborious labor of its own sort, to the people that love Mozart as I do, and hope that everyone enjoys the reading as much as I did the writing.

Prologue

The biography posted at this site covers Mozart's life up until 1791. One could therefore remove the final pages dealing with that year, and append the following additional research material. As with the former material, I haven't gone into a lot of depth on the better-known facts and events, as this is much more a synopsis of his life than a work of deep research.

1791: The year of 1791 saw many great works premiered. Mozart, with the specter of financial calamity always hovering in the distance, due to his (later) admitted gambling problem, strove to regain his fortune and honor at this time by producing more works in shorter times. His music had been changing again over time and works from this last period are noted for their darker-hued tones, a simplicity without losing directness of purpose and their autumnal "feel", which has been described as portraying that everything in Mozart's life at this point was somehow winding down. From this point on though, within this "feel" as it were, there is a wealth of color and rhythm. All of the instrumental sections are now treated with a near-equal importance. The instrumentation is as rich as Brahms's achieved, yet is utterly lucid. There is nothing like this previous to say Cosi fan tutte (where it occurs sporadically). It truly first comes out, in all places, in the dances from the start of 1791. The first major work after those where it again can be viewed is Die Zauberflöte. After that, it was the major centerpiece of his style.

But, 1791 did not start out with any auspicious events. Rather, it appeared to be a foreshadowing to the events of the upcoming December. Mozart performed Piano Concerto # 27 in B flat K.595 as the third item on another performer's concert bill. Mozart was writing music for playing on mechanical organs at a memorial to a dead war hero in order to get a few more ducats. His last great wind concerto, the Clarinet Concerto In A, K.622, was written for a friend who owed him about $28,000 (2006 A. D. conversion) and never paid that debt, despite Mozart's pressing need for money throughout this time.

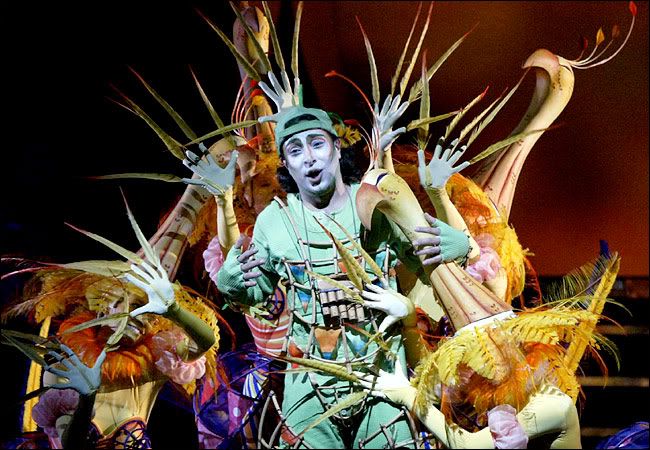

Mozart received a commission on short notice in 1791 to compose an opera seria for the coronation ceremonies of Leopold II in Prague, the city that adored Mozart's operas. Compressing 5-6 months of work down to just over 9 weeks, Mozart gave the festivities there the opera La Clemenza di Tito which was not well received initially. For his friend Emmanuel Schikaneder, owner of a suburban theater in a lower middle class part of Vienna, Mozart was inspired to collaborate with the impresario and his troupe and so the German opera Die Zauberflöte came about. Started on the traditional March 18th date, but put aside for La Clemenza, this work was immediately popular, first in Vienna and then throughout the German states, giving Mozart again the taste of recognition and honor that he had felt before.

By this time, after years of poor monetary luck, it seemed that things began to turn around for Mozart and his family (now with two sons). Mozart was appointed unpaid deputy Kapellmeister to St. Stephen's cathedral in Vienna to help the sick composer Leopold Hoffman in charge there (though not without dissent of certain of the overseeing city council members). This put Mozart in line for the post, which paid about $100,000 a year (2006 A.D. conversion). An amateur musical group in Hungary was offering to buy new compositions from him on subscription as was one in Holland, totaling perhaps another $50,000+ yearly. He had received an offer to go to London and compose for theaters there for at least $120,000 for a year as well. Mozart had an understanding with Johann Peter Salomon, the impresario that had taken Joseph Haydn to England for a successful concert season, to go there as well in 1792. Haydn had made about $250,000 on his tour and Mozart could expect a similar success. Other impresarios were offering opera texts for Mozart to compose music for. All that was required now was patience and the time to choose the most advantageous offers, as many of these could be accomplished simultaneously and without conflict. His musical timing had always been peerless; it now was time for Mozart to get his life in step with these offers.

Mozart's last major composition for 1791 was a Requiem in d minor, commissioned and prepaid by an unnamed messenger acting on behalf of an anonymous amateur composer named Count Franz Walsegg. The Count intended to pass of the work as his own, to honor his dead wife. Constanza was sharply opposed to this course of action, calling it "cheap and unseemly" for a composer of Mozart's stature to undertake. Mozart had taken the work on despite these strange circumstances in the spring of 1791, believing he needed about six or eight weeks to complete it and so acquire the commission. But, with other compositions such as the two operas crowding his schedule, Mozart worked intermittently on the Requiem. Finally, after the premier of Die Zauberflöte in September, he went back to work in earnest. By the middle of November, he had, it would appear, about 35% of it on paper when he fell sick.

And it then seemed that the world was closing in again. Mozart's gambling habits had landed in him many troubles over the years (as it turned out), but his inability to honor a payment promise to Prince Lichnowsky earlier in the year came home to roost now. The Prince, stubborn and careless, sued Mozart for the money owed, and in November he won his case, being able to claim 1460 gulden total. Armed with a warrant, he was authorized to attach Mozart's court salary, and by doing so, bring down disgrace and potential ruin on Wolfgang. Mozart's only secure income was his court salary, which if taken would have surely forced the family out of their home, perhaps even back to Salzburg.

Pork cutlets aside, no one is sure what this defining illness was, though a flare-up of his on-going rheumatic condition is still believed the most likely cause, with added complications. Despite treatments by some of the best doctors in Vienna, Mozart became worse and was confined to bed, his joints swollen, and the pain too great for him to move himself and subject to a high fever. The Prince, in the end having some feelings of propriety, held off on collecting his owed moneys. The Count, on the other hand, feeling he had waited a bit too long, kept pressing, even during this illness, for the finished Requiem. He wanted it by the 15th of January, so that rehearsals could begin on time.

By all accounts, Mozart was at death's door. Had he died then, with no money saved, no pension, and creditors just on the other side of the door, Constanze and his sons would have been put in a precarious situation. No doubt she would have been forced to sell off all the manuscripts then in existance at fire sale prices, in order to survive. Though, given later developments regarding her, she may have found a more creative way to salvage the situation. In any event, Mozart's collapse on December 4-5th was the absolute low point. The application of cold compresses (following the bleeding done by his doctor) to his fevered head initiated this collapse, and Sophie, attending the sick man and so having applied the compress, went into hysterics and had to be restrained by Dr. Closset and Constanze. The ruckus brought in neighbors and eventually the police, but over time things were sorted out and calmed down. Mozart remained totally unconscious for nearly 10 hours, motionless with a barely discernable pulse, before coming around.

At this point then, Constanze wrote "?..I resolved never to face this again, except as being as prepared as anyone one could be, to do so." With Wolfgang weak and totally helpless, she left him in the care of Sophie on December 8th and made her way to see Prince Lichnowsky. In an interview (which she described as cordial yet impassioned; his description of it was instead heated and volatile), she and the Prince agreed, given Mozart's condition, to suspend the attachment of his salary and that all other moneys coming in would go directly to the Prince to pay the outstanding debt (plus court costs). However great his need for the money (and surprisingly, the Prince was in need; he eventually lost everything due to his gambling addiction, a source of future quiet satisfaction to Mozart), the Prince did not want to be seen as kicking a sick man when he was prostrate on the ground. So, he acquiesced to the situation. Given this breathing room, she went back to nursing Mozart back to health so as to get him earning money again.

Selling a performance copy of Die Zauberflöte raised part of the money, as well as several of those of the piano concerti (that were merely laying under the fortepiano) to Artaria. The two godsends that truly eased matters were, of course, the benefit performance Schikaneder gave with Die Zauberflöte and the contract and libretto that showed up for The Tempest. By January 5th, Constanze was able to pay off Prince Lichnowsky just over 900 gulden worth of this debt, and armed with two signed contracts, got him to extend the agreed upon payback deadline. In any event, he was paid in full by the end of March.

To all of this, Mozart gave full credit to Constanze, as well as control of the finances from that time forward. Mozart's standard line from then on, to nearly all people paying or requesting money was "see my wife, she's the manager. I make the music, she handles the money." Their system worked to great advantage the rest of Mozart's life. In appreciation of Constanze's efforts and as well of how close he had come to immortality, he swore off gambling as well. Except for two small slips, he appears to have been clean the rest of his life from that addiction.

================================================== ===============

1792: Mozart, slowly healing, used Süssmayr to help with the task of completing the Requiem as well as The Tempset. Given to recurring bouts of fevers and the fairly crude treatments of the day, Mozart remained sick off and on through the first two months of the year. Given his brush with death, the bold dark colors of the opening of Requiem, in contrast to the warm gentleness of the Benedictus and the hopeful rising chords of the closing Agnus Dei, have made this work one of the highpoints of Mozart's church works. There has always been an on-going controversy as to Süssmayr's actual creative involvement with this work, as we only have as a manuscript the first three main sections (the Introit/Kyrie, Sequence and Offertory) and the Benedictus laid out in readiness by Mozart for a full score. Except for the Lacrymosa, of which only 18 bars were written and an "Amen" fugue sketch worked out, all the movements are fully worked out with four vocal parts a base line. Only the first movement is orchestrated in full. The rest is in Süssmayr's hand. This fact is used to explain the lackings in the remaining movements by the reasoning that Mozart simply had Süssmayr compose them himself, subject to the sick man's approval. The opposing viewpoint simply believes that the sick Mozart was, at this time, not able to effectively compose and that the completion we have is a great tribute to his spirit and tenacity in the face of his desperate illness. What Süssmayr got from Mozart's dictations and sketches were "good enough" for the sick man, who would otherwise have taken much more time in correcting and editing the material. But, of all things, time was not plentiful right then.

For the Count was, if nothing else, persistent. The anniversary of his wife's death was in the upcoming February, he wanted the work for the proper rehearsals to be given. He had waited most of a year for a work promised in six weeks of bestowing the commission. While not a valuable source of commissions, Mozart had benefited from this Count before, and hopefully could do so in the future. His father had always warned him about dallying on projects; he had here and now was annoying a nobleman, to boot. For perhaps the first real time, Mozart probably did not care enough to give the material his full attention. He apparently cared more to get it done and off the table. Perhaps to remove a reminder of his mortality from view, as well? In the case of the Requiem, it apparently did get the bulk of his attention. The quality level speaks of this.

The Tempest, on the other hand, falls back into the category of works exemplified by 1791's Tito, Der Stein and Dervish, where despite patches of truly good work appear, the overall effect is one of disappointment. Especially with The Tempest, Mozart's only foray into the works of Shakespeare. The lament that two great artistic forces could be combined to produce a somewhat lifeless work is the standard line, but Mozart evidently did little more (in his condition) then set what was in front of him. We have no records of any give and take on libretto changes, and given a completion (as noted in his catalogue) of April 5th, 1792, one could expect few. Assuming the Requiem was finished by mid-January, the Tempest then must have taken up only 8 or so weeks to complete. While this is over twice as long as the time estimated for La Clemenza, it is far short of what Mozart used for Die Zauberflöte. This quickness of composition and lackluster result hasn't, of course, kept The Tempest of the boards since it's premiere.

As well, without the stimulus of a theater in front of him (The Tempest was for Hamburg, not Vienna), he appears to have been content to supply music without getting in any way "involved" in the story itself. The recent find of sketches of this work in Süssmayr's hand has lent further credence to the speculation that indeed he may have composed many of the items himself. Given his theater efforts in later years, this speculation has a solid foundation. The existing manuscript itself is over three quarters in his hand, not Mozart's, it matches the printed copies exactly, meaning that another slightly different version in Mozart's hand is very unlikely. We have but one short sketch by Mozart to show that he indeed put any in-depth creative thought in it at all. Given the state of the Requiem manuscript, both of these works remain the mysteries of the later Mozart works.

With the December arrival of Cimarosa in Vienna and the spectacular success of his opera Il Matrimonio Secreto (not to mention his payment of 3500 gulden during his 7 month stay), Mozart knew that, in reality, Vienna was not HIS city right now. How long could he count on that 800 gulden stipend? Schikaneder was pressing him to compose another opera, but he seems reluctant to take up another comic opera, what with Die Zauberflöte doing well, and The Tempest apparently not settling well in his mind. Yet, his monetary needs were precarious then. And so, given the unlooked for offer from England that came across his desk at the end of April 1792, he was either mentally prepared to take bigger risks, or more desperate.

Written by Gary Smith, taken from www.mozartforum.com

----------------------

INTRODUCTION

There has always been the discussion that starts out in some fashion: What would have happened with Mozart, had he lived longer? In most cases, this becomes just idle speculation that he would have composed more symphonies or piano concerti, assuredly met Beethoven, become a full-fledged Romantic composer, and so forth. But this all happens against what backdrop? What might be the other circumstances that would cause some, all or none of these milestones to be achieved?

Who's to say? Well, in this case, it might as well be me. While, as it is said, prediction is an uncertain thing, especially about the future, things can occur to force ones' hands. In this case, when one gets an illuminating flash and sees a timeline and events suddenly present themselves, uncalled for but presented very clearly, then one is impelled to record the information for discussion, if nothing else.

So, I offer this work, the fruits of a long and laborious labor of its own sort, to the people that love Mozart as I do, and hope that everyone enjoys the reading as much as I did the writing.

Prologue

The biography posted at this site covers Mozart's life up until 1791. One could therefore remove the final pages dealing with that year, and append the following additional research material. As with the former material, I haven't gone into a lot of depth on the better-known facts and events, as this is much more a synopsis of his life than a work of deep research.

1791: The year of 1791 saw many great works premiered. Mozart, with the specter of financial calamity always hovering in the distance, due to his (later) admitted gambling problem, strove to regain his fortune and honor at this time by producing more works in shorter times. His music had been changing again over time and works from this last period are noted for their darker-hued tones, a simplicity without losing directness of purpose and their autumnal "feel", which has been described as portraying that everything in Mozart's life at this point was somehow winding down. From this point on though, within this "feel" as it were, there is a wealth of color and rhythm. All of the instrumental sections are now treated with a near-equal importance. The instrumentation is as rich as Brahms's achieved, yet is utterly lucid. There is nothing like this previous to say Cosi fan tutte (where it occurs sporadically). It truly first comes out, in all places, in the dances from the start of 1791. The first major work after those where it again can be viewed is Die Zauberflöte. After that, it was the major centerpiece of his style.

But, 1791 did not start out with any auspicious events. Rather, it appeared to be a foreshadowing to the events of the upcoming December. Mozart performed Piano Concerto # 27 in B flat K.595 as the third item on another performer's concert bill. Mozart was writing music for playing on mechanical organs at a memorial to a dead war hero in order to get a few more ducats. His last great wind concerto, the Clarinet Concerto In A, K.622, was written for a friend who owed him about $28,000 (2006 A. D. conversion) and never paid that debt, despite Mozart's pressing need for money throughout this time.

Mozart received a commission on short notice in 1791 to compose an opera seria for the coronation ceremonies of Leopold II in Prague, the city that adored Mozart's operas. Compressing 5-6 months of work down to just over 9 weeks, Mozart gave the festivities there the opera La Clemenza di Tito which was not well received initially. For his friend Emmanuel Schikaneder, owner of a suburban theater in a lower middle class part of Vienna, Mozart was inspired to collaborate with the impresario and his troupe and so the German opera Die Zauberflöte came about. Started on the traditional March 18th date, but put aside for La Clemenza, this work was immediately popular, first in Vienna and then throughout the German states, giving Mozart again the taste of recognition and honor that he had felt before.

By this time, after years of poor monetary luck, it seemed that things began to turn around for Mozart and his family (now with two sons). Mozart was appointed unpaid deputy Kapellmeister to St. Stephen's cathedral in Vienna to help the sick composer Leopold Hoffman in charge there (though not without dissent of certain of the overseeing city council members). This put Mozart in line for the post, which paid about $100,000 a year (2006 A.D. conversion). An amateur musical group in Hungary was offering to buy new compositions from him on subscription as was one in Holland, totaling perhaps another $50,000+ yearly. He had received an offer to go to London and compose for theaters there for at least $120,000 for a year as well. Mozart had an understanding with Johann Peter Salomon, the impresario that had taken Joseph Haydn to England for a successful concert season, to go there as well in 1792. Haydn had made about $250,000 on his tour and Mozart could expect a similar success. Other impresarios were offering opera texts for Mozart to compose music for. All that was required now was patience and the time to choose the most advantageous offers, as many of these could be accomplished simultaneously and without conflict. His musical timing had always been peerless; it now was time for Mozart to get his life in step with these offers.

Mozart's last major composition for 1791 was a Requiem in d minor, commissioned and prepaid by an unnamed messenger acting on behalf of an anonymous amateur composer named Count Franz Walsegg. The Count intended to pass of the work as his own, to honor his dead wife. Constanza was sharply opposed to this course of action, calling it "cheap and unseemly" for a composer of Mozart's stature to undertake. Mozart had taken the work on despite these strange circumstances in the spring of 1791, believing he needed about six or eight weeks to complete it and so acquire the commission. But, with other compositions such as the two operas crowding his schedule, Mozart worked intermittently on the Requiem. Finally, after the premier of Die Zauberflöte in September, he went back to work in earnest. By the middle of November, he had, it would appear, about 35% of it on paper when he fell sick.

And it then seemed that the world was closing in again. Mozart's gambling habits had landed in him many troubles over the years (as it turned out), but his inability to honor a payment promise to Prince Lichnowsky earlier in the year came home to roost now. The Prince, stubborn and careless, sued Mozart for the money owed, and in November he won his case, being able to claim 1460 gulden total. Armed with a warrant, he was authorized to attach Mozart's court salary, and by doing so, bring down disgrace and potential ruin on Wolfgang. Mozart's only secure income was his court salary, which if taken would have surely forced the family out of their home, perhaps even back to Salzburg.

Pork cutlets aside, no one is sure what this defining illness was, though a flare-up of his on-going rheumatic condition is still believed the most likely cause, with added complications. Despite treatments by some of the best doctors in Vienna, Mozart became worse and was confined to bed, his joints swollen, and the pain too great for him to move himself and subject to a high fever. The Prince, in the end having some feelings of propriety, held off on collecting his owed moneys. The Count, on the other hand, feeling he had waited a bit too long, kept pressing, even during this illness, for the finished Requiem. He wanted it by the 15th of January, so that rehearsals could begin on time.

By all accounts, Mozart was at death's door. Had he died then, with no money saved, no pension, and creditors just on the other side of the door, Constanze and his sons would have been put in a precarious situation. No doubt she would have been forced to sell off all the manuscripts then in existance at fire sale prices, in order to survive. Though, given later developments regarding her, she may have found a more creative way to salvage the situation. In any event, Mozart's collapse on December 4-5th was the absolute low point. The application of cold compresses (following the bleeding done by his doctor) to his fevered head initiated this collapse, and Sophie, attending the sick man and so having applied the compress, went into hysterics and had to be restrained by Dr. Closset and Constanze. The ruckus brought in neighbors and eventually the police, but over time things were sorted out and calmed down. Mozart remained totally unconscious for nearly 10 hours, motionless with a barely discernable pulse, before coming around.

At this point then, Constanze wrote "?..I resolved never to face this again, except as being as prepared as anyone one could be, to do so." With Wolfgang weak and totally helpless, she left him in the care of Sophie on December 8th and made her way to see Prince Lichnowsky. In an interview (which she described as cordial yet impassioned; his description of it was instead heated and volatile), she and the Prince agreed, given Mozart's condition, to suspend the attachment of his salary and that all other moneys coming in would go directly to the Prince to pay the outstanding debt (plus court costs). However great his need for the money (and surprisingly, the Prince was in need; he eventually lost everything due to his gambling addiction, a source of future quiet satisfaction to Mozart), the Prince did not want to be seen as kicking a sick man when he was prostrate on the ground. So, he acquiesced to the situation. Given this breathing room, she went back to nursing Mozart back to health so as to get him earning money again.

Selling a performance copy of Die Zauberflöte raised part of the money, as well as several of those of the piano concerti (that were merely laying under the fortepiano) to Artaria. The two godsends that truly eased matters were, of course, the benefit performance Schikaneder gave with Die Zauberflöte and the contract and libretto that showed up for The Tempest. By January 5th, Constanze was able to pay off Prince Lichnowsky just over 900 gulden worth of this debt, and armed with two signed contracts, got him to extend the agreed upon payback deadline. In any event, he was paid in full by the end of March.

To all of this, Mozart gave full credit to Constanze, as well as control of the finances from that time forward. Mozart's standard line from then on, to nearly all people paying or requesting money was "see my wife, she's the manager. I make the music, she handles the money." Their system worked to great advantage the rest of Mozart's life. In appreciation of Constanze's efforts and as well of how close he had come to immortality, he swore off gambling as well. Except for two small slips, he appears to have been clean the rest of his life from that addiction.

================================================== ===============

1792: Mozart, slowly healing, used Süssmayr to help with the task of completing the Requiem as well as The Tempset. Given to recurring bouts of fevers and the fairly crude treatments of the day, Mozart remained sick off and on through the first two months of the year. Given his brush with death, the bold dark colors of the opening of Requiem, in contrast to the warm gentleness of the Benedictus and the hopeful rising chords of the closing Agnus Dei, have made this work one of the highpoints of Mozart's church works. There has always been an on-going controversy as to Süssmayr's actual creative involvement with this work, as we only have as a manuscript the first three main sections (the Introit/Kyrie, Sequence and Offertory) and the Benedictus laid out in readiness by Mozart for a full score. Except for the Lacrymosa, of which only 18 bars were written and an "Amen" fugue sketch worked out, all the movements are fully worked out with four vocal parts a base line. Only the first movement is orchestrated in full. The rest is in Süssmayr's hand. This fact is used to explain the lackings in the remaining movements by the reasoning that Mozart simply had Süssmayr compose them himself, subject to the sick man's approval. The opposing viewpoint simply believes that the sick Mozart was, at this time, not able to effectively compose and that the completion we have is a great tribute to his spirit and tenacity in the face of his desperate illness. What Süssmayr got from Mozart's dictations and sketches were "good enough" for the sick man, who would otherwise have taken much more time in correcting and editing the material. But, of all things, time was not plentiful right then.

For the Count was, if nothing else, persistent. The anniversary of his wife's death was in the upcoming February, he wanted the work for the proper rehearsals to be given. He had waited most of a year for a work promised in six weeks of bestowing the commission. While not a valuable source of commissions, Mozart had benefited from this Count before, and hopefully could do so in the future. His father had always warned him about dallying on projects; he had here and now was annoying a nobleman, to boot. For perhaps the first real time, Mozart probably did not care enough to give the material his full attention. He apparently cared more to get it done and off the table. Perhaps to remove a reminder of his mortality from view, as well? In the case of the Requiem, it apparently did get the bulk of his attention. The quality level speaks of this.

The Tempest, on the other hand, falls back into the category of works exemplified by 1791's Tito, Der Stein and Dervish, where despite patches of truly good work appear, the overall effect is one of disappointment. Especially with The Tempest, Mozart's only foray into the works of Shakespeare. The lament that two great artistic forces could be combined to produce a somewhat lifeless work is the standard line, but Mozart evidently did little more (in his condition) then set what was in front of him. We have no records of any give and take on libretto changes, and given a completion (as noted in his catalogue) of April 5th, 1792, one could expect few. Assuming the Requiem was finished by mid-January, the Tempest then must have taken up only 8 or so weeks to complete. While this is over twice as long as the time estimated for La Clemenza, it is far short of what Mozart used for Die Zauberflöte. This quickness of composition and lackluster result hasn't, of course, kept The Tempest of the boards since it's premiere.

As well, without the stimulus of a theater in front of him (The Tempest was for Hamburg, not Vienna), he appears to have been content to supply music without getting in any way "involved" in the story itself. The recent find of sketches of this work in Süssmayr's hand has lent further credence to the speculation that indeed he may have composed many of the items himself. Given his theater efforts in later years, this speculation has a solid foundation. The existing manuscript itself is over three quarters in his hand, not Mozart's, it matches the printed copies exactly, meaning that another slightly different version in Mozart's hand is very unlikely. We have but one short sketch by Mozart to show that he indeed put any in-depth creative thought in it at all. Given the state of the Requiem manuscript, both of these works remain the mysteries of the later Mozart works.

With the December arrival of Cimarosa in Vienna and the spectacular success of his opera Il Matrimonio Secreto (not to mention his payment of 3500 gulden during his 7 month stay), Mozart knew that, in reality, Vienna was not HIS city right now. How long could he count on that 800 gulden stipend? Schikaneder was pressing him to compose another opera, but he seems reluctant to take up another comic opera, what with Die Zauberflöte doing well, and The Tempest apparently not settling well in his mind. Yet, his monetary needs were precarious then. And so, given the unlooked for offer from England that came across his desk at the end of April 1792, he was either mentally prepared to take bigger risks, or more desperate.