IV. Two Crowns for Two Kingdoms

Two Crowns

Two Crowns

Ironically, Charles I passed away during one of the coldest days of the year, even as he had seized the throne. His son, Charles of Cornwall, was declared Charles II by the people of London, although his coronation (like many) was delayed for some months.

Charles of Cornwall never expected to become king. The youngest son of a relatively minor Lancastrian lord, there were a dozen more likely men who could have become king had his father not seized the moment and had himself crowned that winter day during the siege of London. Even then, his elder brother John was considered to be the new heir to the throne until his death from scrofula. John was the favored son; Charles was neglected by his father until he became the only son.

It is telling that it is precisely because of these circumstances that Charles became one of the greatest kings that England has ever known.

When he ascended the throne, Charles II was still an enigma to the court. Like his late brother John, Charles preferred to stay far away from Parliament on his estates. But while John had spent his time indulging in falconry and womanizing, Charles preferred to spend his time taking charge of the affairs of his estates. In fact, although he had been granted only a minor fief in Cornwall from his father, his lands had become more productive than his brother's by the time the latter died in 1470. With a reputation for strict honesty, fairness and efficiency, Parliament naturally wondered what the new king would be like in London.

A first taste of his style of rule was not long in coming. The new monarch spent several weeks reorganizing the court to his fancy, replacing many of his father's favorites with more capable men. He had no shortage of applicants, but Charles was a shrewd judge of character and more interested in a man's ability than his credentials. Despite this, he sent away few men disgruntled, being able to convince many a man his talents were needed elsewhere. But two applicants in particular caused the court to hold their collective breaths.

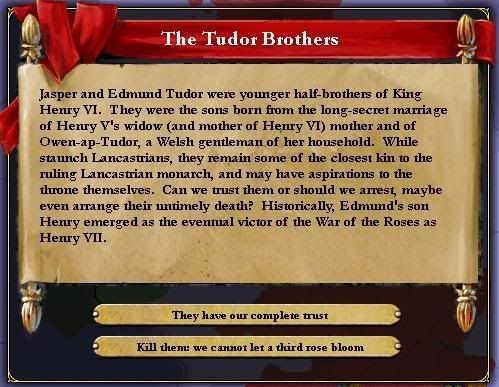

Jasper and Edmund Tudor were the younger half-brothers of Henry VI, born of a liason between Henry's mother Catherine and Owen-ap-Tudor, a Welsh gentleman. Although bastards, they had a legitimate claim to the throne - and arguably a better one than Charles himself had. Charles immediately welcomed the brothers to court and gave them positions of great responsibility, publicly declaring to all his complete trust in the brothers - a decision he did not have cause to regret. From that point on the House of Tudor's fortunes rose and fell with England's.

1476 was a busy year in London. Charles' court was bustling with changes and plans, yet despite all the gains in efficiency there was remarkably little concrete to show for it. To the average layman, Charles seemed little different than his father; life would go on as normal for England. The first sign that things might be difference came the following winter.

It was in December that Charles began mixing Celtic soldiers in his English armies. Scottish and Irish Galloglaigh troops had long been the bane of the Anglo-Saxon troops in the north or the Pale, fierce mercenary warriors who were deadly in close combat and famed for their surprise attacks. Despite initial resistance from the rank and file, Charles was able to seamlessly integrate the two forces, making them much tougher overall.

The change was soundly protested by Parliament, but still toothless they were unable to do much more than grumble. There were some who called Charles II a traitor, but they were won over by Charles and his young queen, Caroline of Scotland. When Stuart I had approached Charles to arrange a marriage between their houses, both kings agreed to the marriage believing that it would never threaten their rule. Charles, after all, was not the heir to the throne, and Stuart had sons and cousins waiting to inherit. When the Scottish king broke the marriage treaty and invaded, some called for Charles to send his wife and children back to Scotland, shamed, but the young lord refused. Instead, the bride and groom waited in growing horror as they heard of Stuart's last stand and John Knox's bloody conquest of Edinburgh castle.

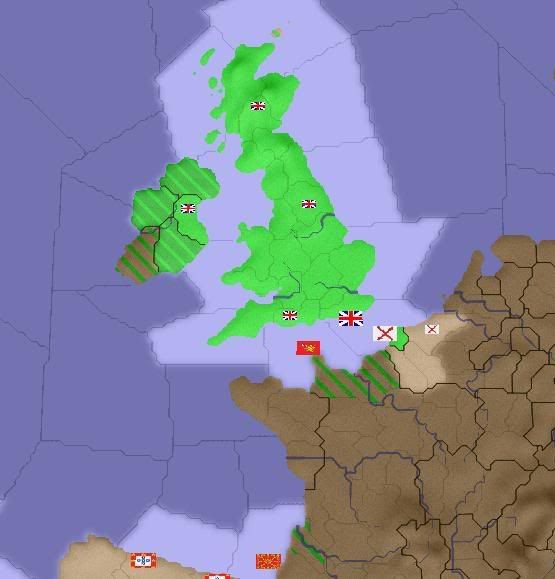

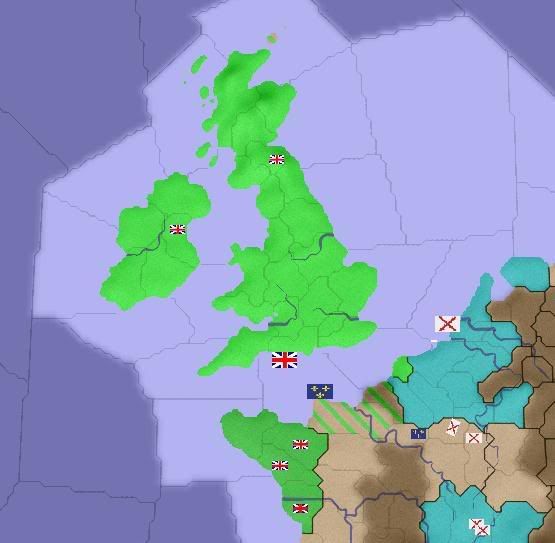

Charles I believed he had stamped out the Scottish royal line; Charles II revived it. He could claim with some legitimacy two crowns: as son of Charles I, he was king of England, but as son-in-law of Stuart, he could claim the throne of Scotland as well. With the northern kingdom already in his hands, it was a fait accomplit, and when Charles asked to be crowned in Edinburgh Parliament readily agreed.

And so, on Wednesday, March 29th, 1477, Charles was crowned in Scotland, with a host of English, Scottish and even Irish lords and ladies in attendance, much to their mutual displeasure. It came as a shock to all, however, what happened next. By the grace of God, Charles of Cornwall was crowned Charles II, king of the United Kingdoms of the English and Celts, and claiming all of Great Britain as his birthright.

March 29, 1477, a day that will live in schoolboy's textbooks forever

1477 map showing the extent that Charles II claimed for the nascent 'United Kingdoms'

Charles was met with disbelief, but he stubbornly pressed his claims and, with charm more than force, gradually won over the lords to his side. Charles was a gentleman, a true noble in all senses of the word. He had a rare talent of knowing how to win loyalty and persuade his enemies, and he combined that with a tireless dedication to his calling that left the United Kingdoms in far better hands than England or its new united kingdoms had seen for decades. Since he was publicly disliked by his father he could win over the Yorkists to his cause, but as a true Lancastrian heir he won over his family as well. Married to a Scottish princess, he adapted to their ways easily and became especially well loved there for the money he spent there lavishly, much to the chagrin of Parliament (there is still a Scottish distiller that uses his coat of arms on its label). In Ireland, his claims to the throne were more convoluted and more divisive, with both Irish and Englishmen on both sides of the issue. Curiously, the only group who wholeheartedly supported his claim to Ireland were the Scots.

It was Ireland that Charles was to focus on. His efforts for the next few years were spent winning the Irish earls over to his United Kingdoms with a three-pronged effort: granting titles and lands to the earls, subsidizing a nascent middle class there which would see British unity as a blessing for commerce, and creating a powerful army and navy as a show of force. His policy bore fruit when many of the northern earls swore fealty and became lords of Great Britain, including the Duke of Ulster.

Further inroads into Eire were stymied for some time as the Irish were upset by the deposition of the pope in Europe. Having fled Rome to a new holy see in Auvergne, the holy father was - in a fit of cosmic irony - deposed by the count of Avignon, a former Roman possession. Although Charles was a staunch Catholic, his attention was captured more by the news from the east: Sweden was forced into a humiliating peace with Muscovy, giving up most of their possessions to the schismatic Slavs. As things heated up at home, things got worse on the Continent as well: the Holy Roman Empire declared that a landless pope was in the interests of the empire, while Hungary collapsed in the face of a Turkish invasion, giving control of the Balkans to the Ottomans in one fell swoop. However, by early 1479 it looked like things were settling back to normal, and Leinster was proving receptive to his overtures when everything changed.

On February 3, France declared war.

The False War

Although Charles had made some strides towards making the United Kingdoms a military power, France still held all the cards in 1479. Allied to Burgundy, France and Burgundy together had over 40,000 men under arms in the north, while Calais was almost defenseless. In the isles the British had around 21,000 men under arms, with little to no support from their Irish allies.

On the continent there was a race between Henri II of France and Claude de Marle of Burgundy to see which could take Calais first (the last British town there fell two months later). Charles retaliated by sending the Scottish army into the Orkney isles, owned by France's ally Norway. In the meantime, he began a diplomatic offensive: first he replaced his spymaster with a mastermind, the infamous 'Lord Black' whose true identity is still unclear, centuries later. Then he arranged with the archbishop of Utrecht to allow his troops to use their lands as a staging point for raids into Burgundy.

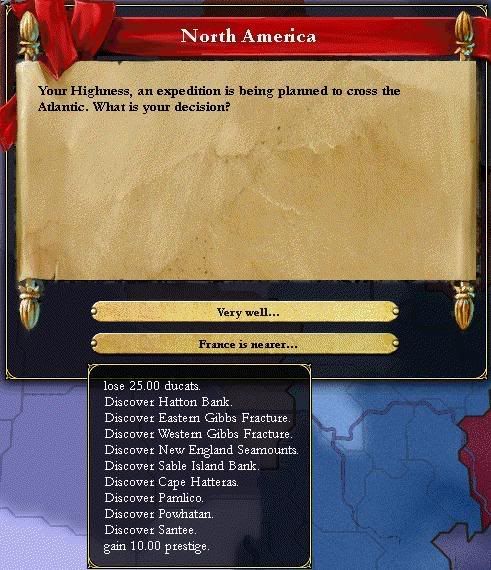

At the same time, the crown financed the purchase of a number of new ships called 'barques' from the Continent using a new, more manueverable style that made them deadlier in combat. The new navy was unable to do much, however, being trapped in port by a fleet of over 20 Burgundian warships. Lacking experienced commanders or veteran sailors, Charles decided not to test the Franco-Burgundian navies. Instead, the United Kingdoms followed a bold new policy, unheard of in its history.

It ignored the war.

Leaving the English towns of Calais and Dunkirk flying the fleur-de-lis, Charles used his new navy to hunt Burgundian privateers and French raiding parties in Ireland. The French raids, designed to remove the Irish allies from the war, only made them realize how much they depended on the British armies stationed there. In the meantime, Charles kept taxes low and spent his money building roads in Scotland, fulfilling promises made at his coronation and enriching the north considerably. By 1483, the new Scottish Bourgeoisie had gained enough strength to demand concessions from the crown, which Charles granted; this proved beneficial to the burgeoning shipbuilding industry in the north.

This 'false war' continued for several years. Despite their naval superiority, the French were unable to land more than a few thousand troops at a time in the British isles and, wrongfully perceiving the real war to be in France as it had for the last century, never invaded Britain in force. Expecting a counter attack at any moment, the French continued to maintain their forces at full strength and taxed their people heavily to pay for the war. Although they maintained their grip on Calais, the French were losing the war of public opinion with each ship sunk and each invasion defeated. In comparison, in England Lord Suffolk was able to use the war as an excuse to bring order to the United Kingdoms, something that had proven impossible for the young king to do in peacetime.

Pirates and Privateers

But as much as France was hurting, the United Kingdoms were still far from winning the war. With only a limited control of the seas, the British had no way to regain Calais, let alone fight the war. By 1484 Charles signed orders that led to a new phase in the war: the British navy began picking off isolated French and Burgundian ships ferrying soldiers to the isles. These raids were by and large successful, but not without a price: several British ships were sunk in the process, despite the introduction of new cast bronze mortars. Still, these naval battles convinced Charles that the strategy could work.

The following year the king promoted Jeremy Herbert, one of the ship captains in the raid of St. George's channel, to admiral of the navy. Sir Jeremy made only a passable admiral, but there were few other candidates. Under Herbert the royal navy continued to win minor engagements, but stayed far from the English Channel.

Around Christmas, 1485, Charles II made a momentous decision to begin attacking shipping in the channel. His decision was probably influenced by the heady celebration going on at court at the time; Sir Joseph Benblow's incredible astronomical discoveries had brought much prestige to the United Kingdoms in international circles, and Charles was seeking a quick victory.

In March 1486 the royal navy intercepted a French ship isolated from the main fleet. Despite reports that the French fleet might be as close as a few hours away, Sir Jeremy decided to take the risk. The result was the fateful battle of Land's End, in which 12 English warships fought 15 French ships under one of the most capable French admirals. At the time it was thought to have been a French trap, but later evidence suggests that it was pure luck - if not entirely unsurprising. The result was no more surprising: the royal navy was decimated, with a few surviving ships limping back to Cornwall.

A contemporary folk song records the popular feelings of the time. With the French in control of the channel, many of the ships and their sailors came from the north; they were upset when the fleet was destroyed. However, far from rebelling against the king or the war, the blame was placed squarely on the shoulders of the lord admiral, Jeremy Herbert. This is typical of the charisma that characterized the court of Charles II.

Herbert's Navy

Where did all our young men go?

Hey-di Hi-di ho la

Off to England, row by row

Hey-di Hi-di ho

Old Laird Herbert built a navy

Built it out of forest green

Said the laird "the French will pay,

Dearly for all the death we've seen"

Where did all our young men go?

Hey-di Hi-di ho la

In the navy, row by row

Hey-di Hi-di ho

Old Laird Herbert sailed his ships

Sailed them to the shining sea

Said the laird "the French will pay,

We'll hunt their ships day after day"

Where did all our young men go?

Hey-di Hi-di ho la

To the channel, row by row

Hey-di Hi-di ho

Old Laird Herbert saw his chance

Saw a fleet of ships that day

Said the laird "the French will pay,

Let the dice roll where they may"

Where did all our young men go?

Hey-di Hi-di ho la

Up to Heaven, row by row

Hey-di Hi-di ho

Old Laird Herbert sailed home alone

Sailed one lone ship back to port

Said the laird "The French did pay,

But not so much as us to-day."

Where did all our young men go?

Hey-di Hi-di ho la

Off to England, row by row

Hey-di Hi-di ho

Old Laird Herbert built a navy

Built it out of forest green

Said the laird "the French will pay,

Dearly for all the death we've seen"

Where did all our young men go?

Hey-di Hi-di ho la

In the navy, row by row

Hey-di Hi-di ho

Old Laird Herbert sailed his ships

Sailed them to the shining sea

Said the laird "the French will pay,

We'll hunt their ships day after day"

Where did all our young men go?

Hey-di Hi-di ho la

To the channel, row by row

Hey-di Hi-di ho

Old Laird Herbert saw his chance

Saw a fleet of ships that day

Said the laird "the French will pay,

Let the dice roll where they may"

Where did all our young men go?

Hey-di Hi-di ho la

Up to Heaven, row by row

Hey-di Hi-di ho

Old Laird Herbert sailed home alone

Sailed one lone ship back to port

Said the laird "The French did pay,

But not so much as us to-day."

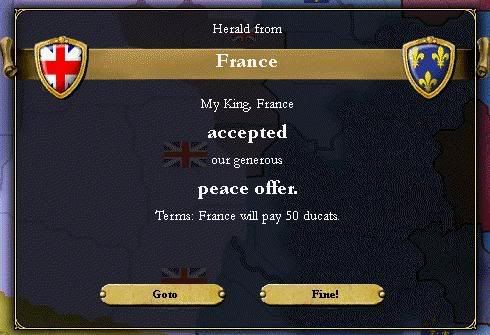

Encouraged by this victory, Henri II offered Charles a peace treaty to end the war that would result in the status quo, and Charles, despairing of any chance of turning the war into his favor, accepted. The ports of Calais and Dunkirk were returned to England while Orkney was returned to Norway, and both sides maintained their honor, so vitally important to both monarchs.

Only a few days after France and Burgundy made peace with the United Kingdoms, Burgundy annexed Switzerland. This overt aggression did one favor for the United Kingdoms: it convinced the pope to turn away from France in disgust and back to England.

Although the United Kingdoms had not won the war, she had achieved her aims: Great Britain had rallied around her king, won the pope's blessing, gained support from her Irish allies, maintained her territory and fought the French to a standstill. Even better was a gift to the state the following spring, in 1487, from Irish earls grateful for British protection during the war.

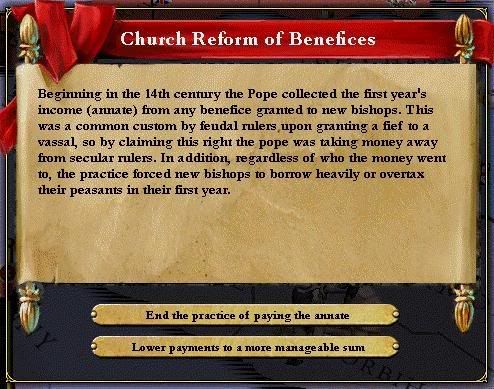

That June the Council of Ostergotland opened, and Charles made good use of his newly-won prestige by sending British bishops to the council and quietly supporting certain resolutions. The council went on to condemn the excesses of indulgence sellers, emphasized the importance of parishes, demanded that bishops supervise their parishes and finally ending the practice of paying annates for church benefices. The council ended on this high-water mark in September 1488. During the council Britain's standing in Christendom had risen substantially as British bishops, outnumbering those from many other Christian nations, had argued eruditely one way or the other.

The main issue of the Council of Ostergotland was that of payment for benefices

Two Kingdoms

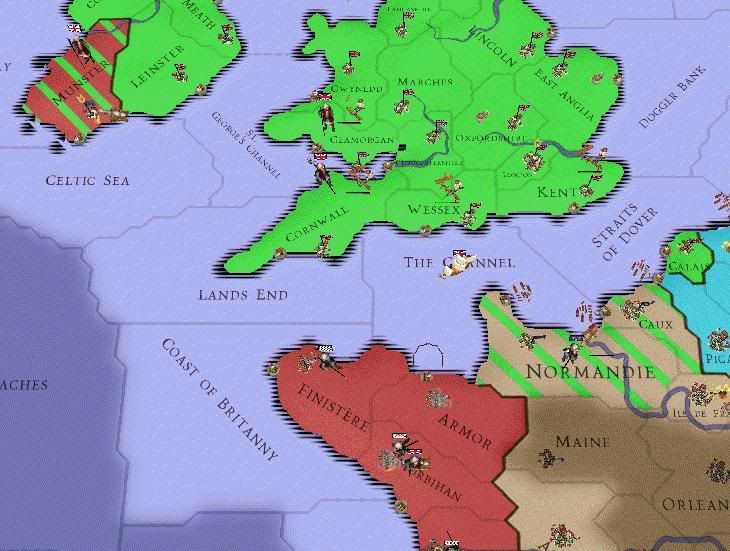

At home, Charles squandered some of this prestige trying to convince the earls to join the Kingdoms. For two long years the Irish showed their stubbornness; finally, in the autumn of 1488, Charles forced their hand by sending his troops into Munster. This brazen act was typical of Charles, designed not only to convince the earls to accept his rule, which they did in short succession, but also for even grander aims. As most of Ireland accepted British sovereignty, Brittany became alarmed. Allied with the earl of Munster, the Bretons declared war on the United Kingdoms when British troops entered Munster, not realizing they were playing into the king's hands.

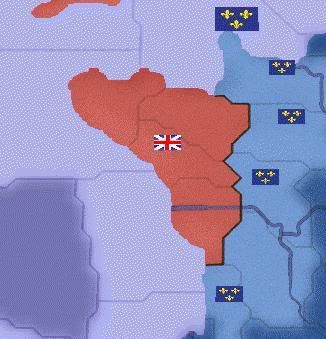

The War of British Unification began in 1488 with the invasion of Munster

Charles had as his goal the unification of all Anglo-Saxons and all Celts under one empire that would stretch from Scotland to Brittany and from Leinster to Anglia. As 'little Britain', Brittany was as much part of the British crown as Ireland. It was painfully obvious, however, that the situation was very different: Brittany was a strong country neighboring France, and the Bretons who lived there had little in common with the Irish, Welsh and Scots who made up the "Celts" of the United Kingdom.

It was unlikely that the French would sit idly by, and in fact French troops massed around the border with Brittany in an ominous manner. A potential conflict was averted, however, when shortly after the war began, Charles received an offer of alliance from the erstwhile French ally Burgundy. With them supporting the British - although merely in spirit - Britain could act unimpeded in Brittany.

A powerful English navy, mainly the powerful new carracks, quickly ferried across English armies into Brittany. Fierce resistance from the Bretons made little difference to the outcome; British troops lost one initial battle and then overwhelmed the defenders. After they won a few towns along the coast, victory was assured.

The invasion of Brittany began in 1489

The pivotal battle of Moribhan, September 1489

Seeing the way things were going, Brittany's Francois II began negotiating in 1490, but only after the last Breton rebels surrendered in March did he even consider serious terms.

The conquest of the Vendee broke the final Breton resistance

In fact, Francois proved remarkably stubborn; even while he was kept prisoner in the Tower of London, Francois resisted becoming a vassal of the king. After a year's fruitless negotiation, Charles was seriously considering simply annexing the country and leaving Francois in charge of a rump Breton state to satisfy the French. It was doubtless the thought of his country being divided that made Francois accept the inevitable; in 1491 he knelt in front of Charles II and pledged fealty to the king of the Britons, and Charles added a new kingdom to his empire.

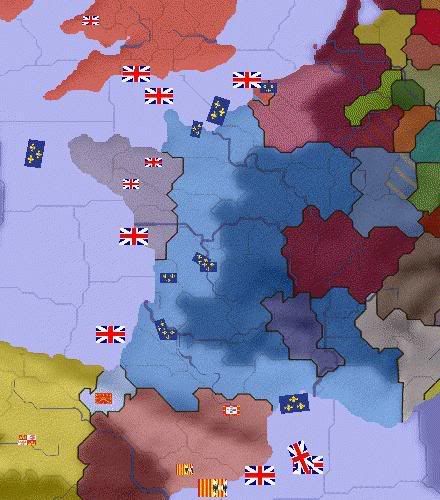

Map of the United Kingdoms in 1491 showing the height of Carolingian power in the Continent.

It is perhaps telling that Shakespeare chose to end his history of Charles II with this diplomatic triumph:

Francois: O, what envenom'd gift the Moirae give;

This matter of Britain! May God forgive

Human frailty; I, no Meriadoc

Indeed, say but a kestrel to his hawk

Can'st not eke out another Nominoe.

Gloat, sir; here you have Bretagne brought low.

[Francois kneels]

Charles: I fear my intentions have gone awry:

Stand! No hawk, sir, but a tercel see I,

Fitting for John, who painted Richmond red

And won a county; My lord, have no dread,

No black poison shines this gift's golden hue

Of opportunity to bid adieu

To the matter of France! May God forgive

Human pride; Disparate, we are captive

To the fates. United, six make a fasces

That cannot break! Hesitation betrays

That noble dream. Swear and be king in Nantes

Or wait, while another awaits detente.

Francois: Honeyed words, majesty, but not untrue.

By vowing, my daughter's birthright accrues

And tho' Bretagne fade to Brittany

Her marriage bed a better jubilee

Than a bier! Generations of pure gold

Can satisfy silver centuries old.

I swear! I am your man, and you high king

Of all the Celts. Let Armorica sing!

Charles II, Act V, Scene V, 201-26

This matter of Britain! May God forgive

Human frailty; I, no Meriadoc

Indeed, say but a kestrel to his hawk

Can'st not eke out another Nominoe.

Gloat, sir; here you have Bretagne brought low.

[Francois kneels]

Charles: I fear my intentions have gone awry:

Stand! No hawk, sir, but a tercel see I,

Fitting for John, who painted Richmond red

And won a county; My lord, have no dread,

No black poison shines this gift's golden hue

Of opportunity to bid adieu

To the matter of France! May God forgive

Human pride; Disparate, we are captive

To the fates. United, six make a fasces

That cannot break! Hesitation betrays

That noble dream. Swear and be king in Nantes

Or wait, while another awaits detente.

Francois: Honeyed words, majesty, but not untrue.

By vowing, my daughter's birthright accrues

And tho' Bretagne fade to Brittany

Her marriage bed a better jubilee

Than a bier! Generations of pure gold

Can satisfy silver centuries old.

I swear! I am your man, and you high king

Of all the Celts. Let Armorica sing!

Charles II, Act V, Scene V, 201-26

Cole's Notes: In this last scene Charles persuades the reluctant king Francois of Brittany to swear fealty to him.

Francois first curses the fates (Gk. Moirae) for forcing him to surrender to the English, one of the two principal enemies of Brittany, then compares his own defeat against the British to Conan Meriadoc's legendary victory over the French in the 9th century in the battle of Nominoe which established Breton independence.

Charles proceeds to turn Francois' speech against him; instead of a kestrel (a servant's bird), Charles compares him to a tercel (a king's falcon) and suggests Francois compare his situation to John the Red, who was born of a union between the Duchess of Brittany and the Earl of Richmond and ended up lord of both domains. The tacit promise in this stanza is that Francois' only child Mathilda will have children who rule over both England and Brittany. Charles also suggests that France is the real enemy, just waiting for the chance to conquer Brittany, and that by allying themselves with England they can defy the fates and retain their autonomy. The fasces metaphor is another Roman symbol - the bundle of sticks carried by consuls - that Charles uses to make his point. The six are, of course, the six Celtic nations of Scotland, Ireland, Wales, Brittany, Cornwall and the Isle of Man.

After hearing all these arguments, Francois gives in and agrees that his daughter Mathilda will marry Charles' son Frederick, uniting the two nations at some future date. He believes that these grandchildren (the generations of 'pure gold') will be enough to prevent an uprising in Brittany - the Armorica of Roman times - by suggesting it will honor his ancestors (the 'old silver'), coming back a final time to Shakespeare's precious metal metaphor.

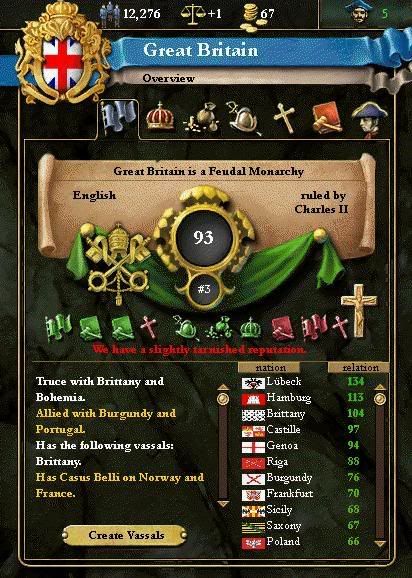

The United Kingdoms at a Glance in 1491

Treasury: 73 million ducats

Estimated GDP: 398.4 million ducats

Standing Army: 18,000 Landsknechten and 9,000 knights

Reserves: 13,000

Royal Navy: 9 small ships and 6 transports

Prestige: 3rd highest (93.1)

Reputation: Slightly Tarnished (3.32/23)

Last edited: