From Rus to Russia - Russia Megacampaign, pt.2

- Thread starter unmerged(59077)

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Really cracking stuff. I've read a bit about Mongol history myself, nowhere near enough though, and its a very fascinating subject. As ever the detail in your updates is simply astounding and I especially like the map.

Kir sounds a good name for a dog. It is alot better than the Yorkshire Terrier I look after for my sister, who named her Tiny. Aptly named but I always feel a bit of a tool when yelling out her name during walks...

Kir sounds a good name for a dog. It is alot better than the Yorkshire Terrier I look after for my sister, who named her Tiny. Aptly named but I always feel a bit of a tool when yelling out her name during walks...

Everything is so beautiful. Into the hands of health care. However, if you leave space at the beginning of the line would be super. I think I have an obsession. But the truth is this.

Khublai Khan didn't leave a single stone unturned in East Asia, did he?

And never mind Alexis Colby or Angela Channing, they had nothing on Mongol matriarchs

And never mind Alexis Colby or Angela Channing, they had nothing on Mongol matriarchs

Wonderful Yuan update! Your history book, like your narrative, is fascinating to read. You should write textbooks if all else fails--your language makes the history come alive.

Replies to replies:

asd21593: I try, but great graphics take by far the most time. I am sometimes tempted to write more and make less graphics. Not that this in any way excuses my absense of late, but it was project crunch time at work, so...

General_BT: you flatter me, sir

I actually think I overuse certain phrases, a lot. Still. Thank you.

aldriq: Yes, Mongol royal ladies were rather mean old grandmas. The kind of grandma that could order your nails pulled out and then go right back to playing with the kids. And Khubilai was busy, yes, though his successors are decidely lesser men.

Kommunaut: thank you!

Erturkhan: alright, I will try to leave the leading line empty.

MorningSIDEr: thanks. This is a middling amount of detail but cramped into a short update, agreed, it looks like a lot. I will be returning to China once in a while, as the story progresses.

As for the dog: well, he's grown quite a bit now (and yes, I know, that's how long it's been!), so I can't call him "Tiny" even if I wanted to.

Enewald: The Yuan is still there in 1393; or at least they CLAIM to be the Yuan.

ComradeOm: yes, this is very near-historical. The major differences are in the West and how I moved populations around here and there.

Vesimir: Mount and Blade, correct. All of that is MnB stuff.

Kir is for Cyrus the Great.

Thanks everyone. I plan to get updating again soon.

asd21593: I try, but great graphics take by far the most time. I am sometimes tempted to write more and make less graphics. Not that this in any way excuses my absense of late, but it was project crunch time at work, so...

General_BT: you flatter me, sir

I actually think I overuse certain phrases, a lot. Still. Thank you.

aldriq: Yes, Mongol royal ladies were rather mean old grandmas. The kind of grandma that could order your nails pulled out and then go right back to playing with the kids. And Khubilai was busy, yes, though his successors are decidely lesser men.

Kommunaut: thank you!

Erturkhan: alright, I will try to leave the leading line empty.

MorningSIDEr: thanks. This is a middling amount of detail but cramped into a short update, agreed, it looks like a lot. I will be returning to China once in a while, as the story progresses.

As for the dog: well, he's grown quite a bit now (and yes, I know, that's how long it's been!), so I can't call him "Tiny" even if I wanted to.

Enewald: The Yuan is still there in 1393; or at least they CLAIM to be the Yuan.

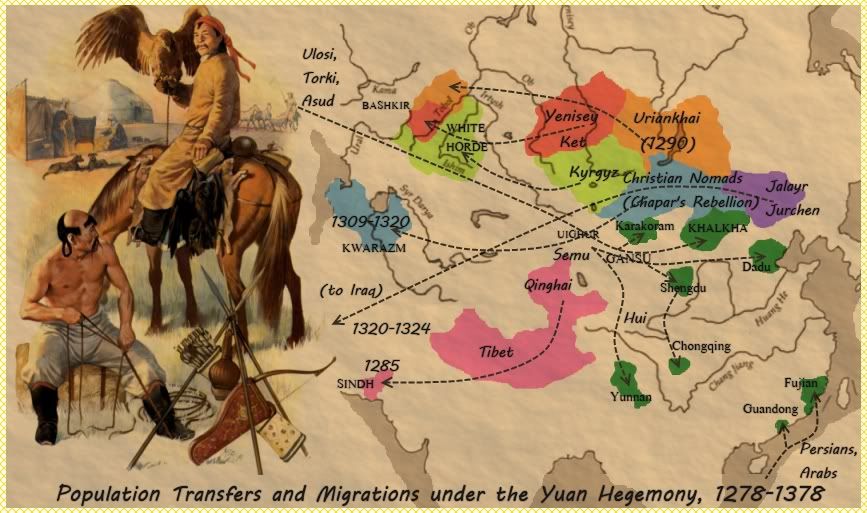

ComradeOm: yes, this is very near-historical. The major differences are in the West and how I moved populations around here and there.

Vesimir: Mount and Blade, correct. All of that is MnB stuff.

Kir is for Cyrus the Great.

------

Thanks everyone. I plan to get updating again soon.

The Yuan Empire and its Aftermath - part 2

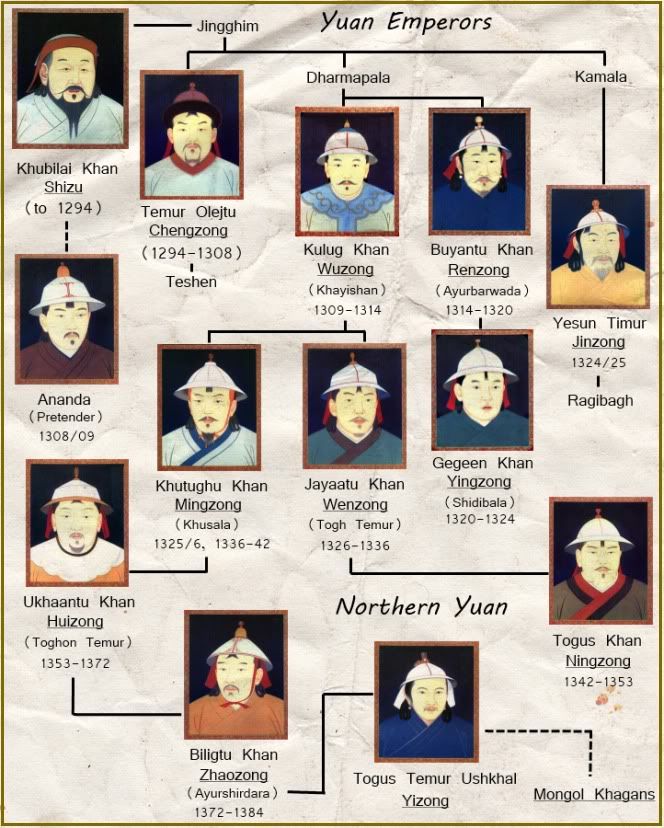

The Middle Yuan

The Mongols settled in China as conquerors, but before long they found themselves as administrators who were often out of their depth. To run their Empire, they relied on the Westerners (Muslims, Buddhists and Christians) as well as the Chinese themselves. Those factions often fought against each other, and even in a relatively tolerant Mongol milieu cultural conflicts sometimes required intervention by the government, which didn’t always change things for the better.

In 1302, Chengzong proclaimed the first of Revere Confucius edicts; this was meant to accommodate the Chinese members of the Imperial structure. The Confucian officials, however, wasted little time in identifying the greatest threats to their prosperity, and that was the entrenchment of the Semu-ren in various sectors of public and commercial life. In 1306, an edict was passed against Jews and Muslims in their meat slaughter traditions; this was ostensibly deemed offensive to traditional Mongols, but was largely used as an excuse by others to wrest the lucrative food trade away from those minorities, as the Mongol diet was heavily meat-based and herding was the occupation of vast areas of the state.

Upon the deaths of Temur and his son, the Nestorians were in turn targeted. The Eastern Christians had, besides a heavy involvement in money-lending, an almost complete monopoly on health services and professional surgery and medicine trade, and the Khans’ deaths were used as proof of their malice. Targeted along with the city Nestorians (mostly Persians and Uighurs) were the Nestorian tribes of the Mongol borderlands, including the Naimans, Kereits and Merkits. This led to a fight against Bulughan of the Bayud, the Emperor’s widow, headed by Chapar son of Kaidu. Chapar and the tribes ultimately lost, and took refuge with the Nogai horde, further swinging the balance of population of the Nogai Khanate towards the Christians.

Ananda, Bulughan’s chosen successor, was a friend to Muslims and reversed the 1306 edict and allowed a new influx of the Semu-ren into the Empire. In 1309, however, Ayurbarwada and Khayishan, of the Khuggirat branch of the House of Khubilai, led a rebellion to overthrow Ananda and Bulughan. The brothers agreed to rule together, but the former’s pro-Chinese tendencies instilled by his Confucian tutors clashed with the latter’s expansionist militarism. Ayurbarwada stepped down with the promise of taking over after his brother, on the condition that their sons would also alternate rule. Khayishan began rule as Kulug-Khan. Salt state monopoly is established in 1310, the money used to build forts and shipyards, and a military road to run north to south. Great Embassy of Kulug to South East Asian states by sea was instituted, collecting tribute, and including Ceylon and Malabar. In 1313, a Timurid-Chaghatid expedition was launched into Delhi, and ended once again in defeat. Timurids, in their weak state, acknowledged Seljuk overlorship and adopted Islam as a result of being integrated into the Seljuk system. Purges of Christians, Buddhists and Shamanists soon followed as the Khans sought legitimacy in Persia and Khorasan. The Yuan Emperor was not consulted about any of these matters.

In 1314, Kulug-Khan died, and Ayurbarwada took over as Buyantu-Khan, Emperor Renzong. His stated focus was to redesign the governorship of the Empire and set it up for a stable posterity. To that end, systematization of the Kublai edicts to be used in the future law and examination process was ordered, not to be completed until 1317. In 1315, the Emperor ordered the restoration of the entrance examination systems, with neo-Confucian studies as the focus. Han subjects got an ethnic quote allowance in the governance; finally, a project to unify the princely Mongol courts and the civil Chinese courts was tabled. All three were stymied in their implementation by the survivors of his brother’s cabinet. Furious, Renzong spent the next few years purging the ministers and ordered the removal of his brothers’ sons from the court in Dadu, breaking his old promise. Temuder-noyon, a key figure of the period, was set as prime minster to centralize the government, and the state acquired a lucrative iron monopoly. By 1317 it was obvious that attempt to reform examinations would be met with disapproval from Confucians who otherwise backed the Emperor. A parallel examination system was set up for Mongols and Semu people, dealing mostly with practical issues, such as geography, law, mechanical studies, Mongol history and commerce. In 1320, Buyantu Khan died; his son Gegeen Khan (Shidibala) was enthroned by his grandmother and Temuder. Both of his protectors soon died in 1322, leaving him alone.

To his credit, he lasted two full years on the throne. During the time, Shidibala persecuted Muslims, forbidding them to engage in slave trade (where they were very active) and from taking North People Examinations. He also continued pro-Confucian policies, repressing the traditional freedoms of North People women. Jalayr tribe, long a vital military component, split under this pressure into Muslims (exiled/migrated to Iraq) and Jurchen Jalayrs, who would later reappear as a coherent state in the Sunghari basin. In 1324, he was overthrown by the traditional Guard; Yesug Temur Khan (backed by the oppressed Muslims hoping to reverse the situation) was asked to be Emperor, only to be immediately opposed by the South Western Army, championing Khulug's sons Khutughtu (Kusala) and Jayaatu (Togh Temur). Yesug Temur was defeated and executed by the brothers' supporters, including the Christian Kipchak Guard captain El Temur and Nestorian Bayan of the Merkits, with whose rise the Nestorian persecution in the Yuan ended.

Kusala was at first sole Emperor, but soon there developed a struggle between him and El Temur. He came to an agreement similar to Byuantu and Khulug's with his brother, leaving the throne temporarily. Togh Temur reigned until 1336, establishing Confucian morality and a Confucian learning academy. His forces, however, were defeated in the West due to his lack of interest in the military; he was rescued from defeat by Bayan, who thereafter entrenched in Dadu and fell into intense rivalry with El Timur. Togh Temur’s reign oversaw the re-establishment of Princely courts and lowering the Han quota for Imperial Examination under pressure from his Semu protectors, a drastic reversal of previous policies. Following his death, his brother took the throne. Bayan and El Temur immediately fell into a struggle for power, and Bayan won. El Temur and family were executed. Under Bayan’s leadership, the Yuan government experienced anti-Confucian movements and a partial reversion to traditional Steppe structures. Kusala sent another Grand embassy by sea, this time including Okinawa. In response, wokou hit China again, and the Yuan responded weakly.

Between 1336 and 1340, the Yuan defeated the Chaghatai and allowed the allied Blue Horde to recruit from among them. The Blue Khans sent more North People over in gratitude, as guards, among them many Russians who were getting directly integrated into Sarai’s tax base. Bayan died in 1340, eliminated by his nephew Toghtoga and his anti-Chinese policies were relaxed. Following the brief unification of Blue, White, Shaybanid and Chaghatid Hordes under the rule of Sarai, Mongols devastated Europe for two decades in repeated raids that reached as far as Verona and Augsburg. The expansion was followed by plagues, weakening both the Great Khans and the united Golden Horde, and ultimately breaking Sarai’s supremacy over Central Asia. In the 1350s Temurids attacked and defeated the weakened Shaybani and Chaghatai hordes. As a result, the reticent Chaghatais officially converted to Islam, cutting off Chinese trade overland due to lack of a large enough Muslim merchant community following the prior persecutions.

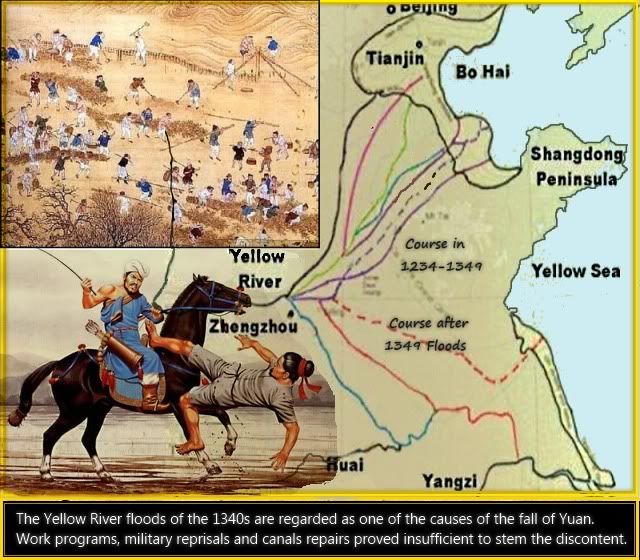

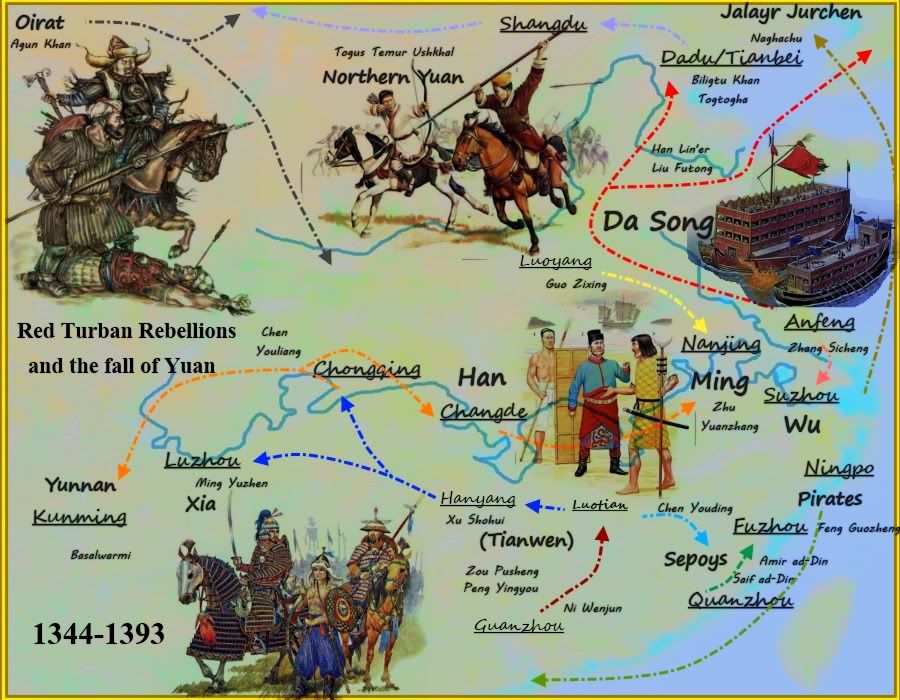

Fall of the Yuan

In 1342, after the death of Kusala, Tegus Khan, son of Togh Temur took over, guided by Toghtoga. Two years later, the new Emperor was facing massive flooding and collapse of the Grand Canal, and the ensuing starvation in the North of China. Plagues broke out in overcrowded refugee tent cities, and followed by White Lotus proselytizing among the disaffected. The terrible situation did not let up; 1349 saw repeated flooding of the Yellow River and harvest failure, followed by the Yellow River shifting course hundreds of miles to the south and covering the most fertile and best-developed part of the Yuan in a layer of silt. Toghtoga was dismissed by Tegus and stayed in exile until Tegus died. Toghun Temur son of Kusala took over in 1353 and recalled Toghtoga. However, the very next year the hastily reconstructed Grand Canal suffered another collapse, and forced labour rounded up to restore it broke into rebellion. The country was spinning out of control; attempts at conciliation with the Chinese were clearly not working.

The years following 1355 saw, in addition to wars with the rebels, struggles between Toghan Temur and his son, crown prince Ayushirdara backed by the generals Koke Temur (of Henan) and Bolad Temur (of Datong); several attempts to enthrone Ayushidrara failed. The court once again blamed Toghtoga; rebellions were contained but not defeated, the house was in disarray. Toghtoga was executed in 1368, and the Crown Prince inflicted a defeat on the rebels (the Later Da Song) that same year. 1372 was marked by the death of Toghan Temur; Biligtu Khan now led the Yuan, which lost all power south of the Yangtzi to increasingly well-organised rebels, with somewhat firmly held front lines around the river. The Mongols then took a risky decision to intervene in Korea to support pro-Mongol faction under King U, who was a victim of a power struggle between Choe and Yi, the leading noble houses of the country. The internal war in the end stopped not because of the Mongols, but to deal with amazingly active and successful wokou who even occupied several coastal fortresses. The Mongols retook Liaodong from rebels, and held on to Dadu. That was the sum of their successes.

In 1378, the Ulosi (Russian) Guards were established, a welcome gift from the Golden Horde to manpower-strapped Yuan; Basalwarmi-noyon of Yunnan defeated attacks of Chen Youliang of the rebel state of Han, retaining his autonomy. Basalwarmi then used the opportunity to funnel tribute to himself instead of the Great Khans. With Yuan fatally weakened, Singhasari attacked Srivijaya, defeating it and forming several smaller vassal kingdoms from its beaten rival, cutting off any tribute by sea. In 1384, with the death of the warlike Biligtu Khan, rebel Da Song resumed advance into Yuan territory, but was repelled at the siege of Dadu after their artillery train was ambushed. Togus Temur Ushkhal Khan was enthroned, with help of Naghachu, prince of the Jurchen Jalayr, whose support proved enough to prop up the Yuan until a famine struck Manchuria in 1387; Naghachu laid down arms, in return for food from the Wu of Suzhou. The Yuan in Dadu were now doomed.

Their homelands threatened by a 1390 Oirat rebellion, the Mongols took the decision to retreat North, though Togus Temur was defeated by the Oirats even there. Da Song captured Dadu by 1391, renaming in Tianbei, Heavenly City of the North, and laying the claim to leading a radically new China. In Korea, the suspended Civil War between the Choe (Choson) and Goryeo (backed by Yi) resumed. The remains of the great Yuan slunk away into the Steppes, accompanied mainly by the remains of the Torki, Ulosi and Asud, though still not quite ready to give up their grand claim to the legacy of Khubilai. Shangdu remained the last major city still in their hands.

A New China Arises

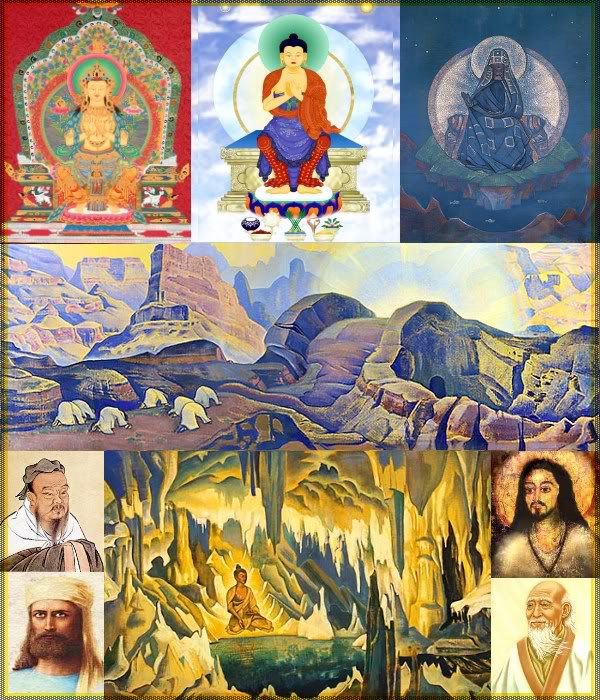

The Yuan Empire, in the end, was not overthrown by a more talented invader, but by a rebellion so deep and broad and breathtaking it has little parallel in history. The revolts centered around the figure of Maitreya, the Future Buddha, which held promise to all; a dangerously attractive idea in class-stratified Confucian China and racially-stratified Yuan. Even as early as the Song dynasty itself, Maitreyan rebellions arose, prompting the government to proclaim the followers heretics and practitioners of unsanctioned religions after a rebellion in Beizhou. When the Yuan weakened, it was ironically with the name of Song that the new wave of Maitreyan rebellion crested. The religion was esoteric and millenarian and besides the unorthodox Buddhist ideals contained parts of Manichean lore, folk beliefs and Daoism, as well as echoes of the Western religions most of the Semu practiced and varied greatly from incarnation to incarnation and leader to leader.

Although Fang Guozhen attacked Yuan officials and started his pirate kingdom as early as 1344, it was in 1353, in the chaos and despair of late Yuan, that a wealthy bureaucrat Han Shantong became leader of the secret White Lotus society. Conspiring with the commander of Chinese Troops Liu Futong, they launched the first Red Turban rebellion, proclaiming The empire is in utter chaos. Maitreya Buddha has incarnated, and the King of Light has appeared in this world. Preachers went around, spreading the sect’s message.

The Unborn Venerable Mother, they said, created Fuxi and his wife, and from them sprang the enlightened beings, and thence humanity. Thus it was the nature of every human to seek their way back to the Heavenly Palace of Western Paradise, where the three still dwelt. “Forebears, Nirvana, Ancestral Lands,” they said, like a password “are achievable by anyone; everyone is equal, sisters and brothers, heirs of the Eternal Ones”. To do so, one had to join the movement, accept the teachings, venerate the Unborn Mother, and follow strictly the words of those higher along the Nine Steps to Enlightenment; at the edge of the last step, Truth would become manifest and the door to the ancestral lands shall open.

Humanity, they said, was in transition. In the era of Blue Sun, Buddha Kashaypa ruled from atop the Blue Lotus. The year was just six months, and the day two watches of six hours, and people have just barely discovered the path to wisdom. This earthly life is spent in the rays of the Red Sun, and from the Red Lotus, Buddha Shakyamuni rules the universe; but the flow of time is slowing, and in the end of this era, those that follow the call of the White Lotus, shall be close to returning to their ancestral paradise. This happy time shall be signified by the rebirth and enthronement of gentle Buddha Maitreya, bathed in the light of the White Sun. However, this momentous event would not occur without human help; to usher in the luminous era of the Kingdom of Maitreya (known to the less enlightened as Amitabha), one must oust the Northern Barbarians from Middle Kingdom.

Han Shantong called himself Ming Wang (King of Brightness), while his son, Han Lin'er called himself Xiao Ming Wang ("Small King of Brightness"); both were portentous names. The Mongols took notice, and the agents of the government caught and executed him; but by then it was too late. Liu Futong proclaimed his ward, Han Lin’er, as Emperor of Latter Da Song, claiming that the man was a direct descendant of the Zhao dynasty dethroned by Khubilai. In the South, in the port cities of Guangzhou and Fuzhou, others joined in, claiming allegiance to Maitreya though not necessarily the Song. In 1354 , Xu Shouhui, a cloth vendor from Luotian and a ranking member of the White Lotus, started an armed revolt and captured the city, turning it into the capital of Tianwen, the heavenly kingdom foretold, ruling it along with his supporters Chen Youliang, Ni Wenjun, Peng Yingyou, and Zou Pusheng. Although the Mongols in Yunnan, with help from the central government briefly defeated him, he returned later and captured Hanyang, making it his new capital. In all this he was assisted by the Manichean general Ming Yuzhen, whose troops occupied Yibin and Luzhou.

To combat them, the Yuan government had raised troops composed almost entirely from muslims from among more than hundred thousand of Semu foreigners that lived in Fujian, led by two Quanzhou Persian generals, Sayif ad-Din and Amir ad-Din. Instead of suppressing the Red Turbans, the muslim "sepoys" siezed Quanzhou, Xinghua (Putian), and finally Fuzhou itself. The government panicked and sent word to the local commanders to raise another force; the commander of the Yuan loyalists was Chen Youding, himself a muslim but of Chinese descent. The government forces at first enjoyed victory, pushing the sepoys out of Fuzhou, but soon ran out of steam, and a stalemate developed. Xu Sohui's forces broke the stalemate by enveloping Fujian from the north. Despite the intense anti-foreigner rhetoric of the White Lotus, Xu's lieutenants showed pragmatism, and sided with the sepoys. After skirmishing with the Tianwen forces, Chen Youding understood his position was hopeless, and offered to join forces with the muslim rebels, stepping in to assume control among the fractioning sepoys. His army split into many components - many joining the rebellion in Fujian, some going over to White lotus, the few Yuan loyalists retreating across Guanxi and into Yunnan to fight for Basalwarmi. Xu was thus outmaneouvred, to the disgust of Chen Youliang, the future King of Han. The muslims remained in control of Fujian and sought peace with Feng the Pirate and by extension the Yuan.

To the East, along the Yangtzi, Zhu Yuanzhang and Zhang Shicheng joined as lieutenants of Liu Futong. Zhu, a farmer's son and carreer soldier, captured Yicheng, later called Nanjing, an important city on the river. Zhang, formerly a salt merchant, settled in Suzhou. Liu’s headquarters were in Anfeng. The fighting went on inconclusively for many years in the North, though it was often the Red Turbans that attacked and the Yuan that defended. Rebel sorties reached as far as Korea, trying to stir up rebellions there, and even conquered Liaodong for a brief time. Meanwhile in the South, Chen Youliang set up Ni Wenjun to look as if he planned to assassinate Xu, the earthly reincarnation of Maitreya. Having rid himself of the rival, he next struck at Xu himself, and although he lost some of the more fervent followers who went North in great unorganized masses to join the Song, he set himself up as Emperor of Da Han, and strongest of all contenders. However, thereafter his military fortunes took a turn for the worse, and, having wasted his troops on aging Basalwarmi in Yunnan, he was unable to complete the domination of the Yangtzi, whose mouths were held by Zhu and Zhang, both claiming to be Kings of Wu, as well as the pirate king Feng from his bases in Ningbo, Zhejiang and Jiangsu.

Having overthrown Tianwei and defeated Peng Yingyou and Zou Pusheng, Chen Youliang sought to end fighting, and signed a secret agreement between Northern Yuan and Da Han; both were afraid of the White Lotus Empire and the Xia of Ming Yuzhen, who never forgave Chen the betrayal of Xu Shouhui. . Zhang (Northern Wu), also having had enough of the war, set his mind on trading with everyone except Da Han and Zhu (Southern Wu/Ming), his immediate rivals, To avoid easy depredation by the latter, he moved the capital from Jiangzhou (Chongqing) to Tingzhou (Changde). The situation looked like a stalemate, until Zhang unwittingly broke it by supplying grain to the Jurchen Jalayrs in exchange for peace and silver. Without support, the Yuan quickly fell to the Song, and in 1392 the Da Song Empire was proclaimed in Dadu, renamed Tianbei. Han Lin’er, a wholly unremarkable man, became the Great Luminous Emperor that replaced Yuan, while his erstwhile allies looked on from the South in fear and mistrust.

Last edited:

Hi everyone.

So the second part of the history of Yuan until 1393 is posted. There's a couple of things I wish to address for greater clarity and to preempt some questions.

The first is, the graphics quality is very rough. That is true, and I promise to keep working on it for future updates; in the meanwhile this is the best I could manage given my rusty skills.

The second is, an attentive reader might ask: RGB, why the slavish insistence on parallelism? Indeed, the differences from OTL are slight whereas by comparison the West of Eurasia is nigh-unrecognizeable. What gives? And what about the characters? Why must this historical universe also contain an Emperor Renzong and even a Zhu Yuanzhang? Why is this setup so much like MEIOU in 1350?

Well, I've got a multipart answer to that. Imagine that various permutations really happened due to some pretty powerful butterflies flapping wings and starting hurricanes. The names should definitely be different, and the events perhaps as well. I was, however, more concerned with keeping the idea of a China full of possibilities three to four decades later than it historically set upon a definite path, and that is why I took my main players directly from history. These are different people - but they are in a similar enough situation and they happen to follow set naming conventions (Buddhist, like say Sidhipala) or Mongol (like the variations of Temur), or in claiming their temple names from pretty stock ideals, and their dynastic country names from those of previously extinct dynasties.

In other words, this done for ease of research and recognition; and an alternate world so similar but with minor differences to our own is possible, if not particularly probable. Just assume it happened here, and something completely different happened in Europe.

And that's my message. Thanks for reading.

So the second part of the history of Yuan until 1393 is posted. There's a couple of things I wish to address for greater clarity and to preempt some questions.

The first is, the graphics quality is very rough. That is true, and I promise to keep working on it for future updates; in the meanwhile this is the best I could manage given my rusty skills.

The second is, an attentive reader might ask: RGB, why the slavish insistence on parallelism? Indeed, the differences from OTL are slight whereas by comparison the West of Eurasia is nigh-unrecognizeable. What gives? And what about the characters? Why must this historical universe also contain an Emperor Renzong and even a Zhu Yuanzhang? Why is this setup so much like MEIOU in 1350?

Well, I've got a multipart answer to that. Imagine that various permutations really happened due to some pretty powerful butterflies flapping wings and starting hurricanes. The names should definitely be different, and the events perhaps as well. I was, however, more concerned with keeping the idea of a China full of possibilities three to four decades later than it historically set upon a definite path, and that is why I took my main players directly from history. These are different people - but they are in a similar enough situation and they happen to follow set naming conventions (Buddhist, like say Sidhipala) or Mongol (like the variations of Temur), or in claiming their temple names from pretty stock ideals, and their dynastic country names from those of previously extinct dynasties.

In other words, this done for ease of research and recognition; and an alternate world so similar but with minor differences to our own is possible, if not particularly probable. Just assume it happened here, and something completely different happened in Europe.

And that's my message. Thanks for reading.

Last edited:

I've been reading up on my Chinese history especially for this update. Sort've. Good thing I did as well because that is a pretty condensed version of an exceptionally complex tale. Interesting to see Han Lin’er survive and re-establish (or at least co-opt the name of) the Song. Parallelism or not, its a pretty significant departure from history if Zhu Yuanzhang doesn't come to the throne, no?

With what troops did Han Lin'er occupy so much land, if other factions would have had their changes to backstab him?

Pretty excellent update. I expected a different fate for the Yuan empire actually, but oh well. Nice touch with the Fujian Emirate

Then... china is divided and had many religions spreading, am i right? Didn't red everything but from what i have red i suppose that world map would realy be interesting...

So Yuan China explodes, and there is no Hongwu readily on hand to mold it historically. This China is far more interesting, with oodles of possibilities that leave someone like me salivating. And hush about your graphics-they're a good balance of informative, pleasant, and simple to understand--unlike mine, which I readily admit often have too many bells and whistles which detract from the image.

And I completely understand about using historical characters--yes, by the butterfly effect none of them should have existed, but its easier for you as an author, and us as readers, to understand what has happened if they remain. Of course, historical characters in ahistorical situations also can make for good fun as well.

And I completely understand about using historical characters--yes, by the butterfly effect none of them should have existed, but its easier for you as an author, and us as readers, to understand what has happened if they remain. Of course, historical characters in ahistorical situations also can make for good fun as well.

Great chapter, it condenses a whole lot of messy history in a very succinct way. It's interesting how the Yuan made China a more cosmopolitan place, and how that internationalism faded away in late Ming and Qing as a counter-reaction. It makes you wonder, if the Mongols had allowed the Han a bit more autonomy from the beginning, China could have been a very different place in the 19th century when the Europeans came knocking...

By the way, you mentioned Korea but not a word about Japan - will it get its own chapter?

By the way, you mentioned Korea but not a word about Japan - will it get its own chapter?

Replies to Replies, and another announcement:

ComradeOm: it's not only condensed, it's at times simplified. However, that could not be avoided. Yuan politics were intense to say the least; Zhu not coming to power to me opens up possibilities in China, yes, and I was aiming at that conclusion with the many many small changes I introduced to an otherwise very similar history. Han Lin'er isn't really the prime mover in Song, Liu Futong is. Does that bode well for the Song? I don't know

enewald: A great question and one that almost blindsided me, except of course I actually did have an answer when I set to writing this. So I dug it up.

Thing was, the northern Red Turbans were the more powerful and the more populist faction even historically, and Zhu only rescued/captured Han Lin'er when the Yuan defeated Liu Futong. Moreover he left him alive until he could deal with Chen and later Zhang. It didn't quite happen that way here. Chen wasted too many men fighting to the west and is more cautious towards Zhu (Zhu's strategy was one of caution and relied on Chen overcommiting); Zhang is still around. Zhu has a lot to worry about. Meanwhile, Liu Futong simply ground down the Yuan who were continuously weakening since the floods of the 1340s. Having everything happen much later really helps that way; I think continuous victories for Red Turbans would win more zealots to their cause.

Now that Zhu has realised that he overwaited the window of opportunity and Liu has captured true Imperial legitimacy for Han Lin'er, he will probably...well. Wait more. He's got more to lose by attacking than by waiting, and the Song themselves probably cannot really enforce their will in the South. Zhang is likewise a wait-and-see guy; Chen is the aggressive one, but he is in no position to threaten too much, so much so that he has to informally ally with the Mongols just to keep his lands in the West safe.

Calipah: I thought you might enjoy it with Fujian; and the Chingisids aren't completely out of the picture yet, though the Imperial period may well be over. Islam may also play a larger role, or at least a more public one, in southern China.

asd21539: Thank you! I hope to deliver more unexpected good stuff in the future, but the future, being the future, is ever uncertain.

Iwanow: China has a profusion of religions held by the different warlords. At the time of upheaval, many that were hidden are actively striving for a chance to improve their fortunes. Fujian is ruled by a mostly-Muslim alliance of Semu and former Imperial army commanders of Han origin. Xia ruled by Ming (in Sichuan/Guanxi) is the Manichean branch of the White Lotus movement. Song themselves are White Lotus buddhists, but they may have to moderate the populist message if they mean to rule. Basalwarmi and the rulers of Yuan are very firmly Tibetan Buddhists, but their population is mixed.

The strong warlord states along the Yangtzi, however, are more traditional, with Confucian ideals overpowering their former Red Turban allegiance. Zhu, Zhang, Feng and Chen Youlian would probably revert to traditional Chinese ideology if they take power, as historically the Ming did (keeping only the dynasty name of the entire Red Turban background).

Yes, China is certainly pretty interesting; but that's almost historical. What isn't is the timeframe shift and the greater likelihood of these factions surviving in the medium to long term.

General_BT: heh. No *Hongwu is a double-edged blessing. He won't be on hand to Confucianise the economy and destroy the currency, but then the Song are far more radical and who knows what they may do? One thing remains for sure: as long as the Song don't take South China firmly in hand, the Semu may well do better than historically and thus keep China engaged to the wider world to a greater extent. On the other hand, that does mean continued political instability.

And yes, without the historical characters being themselves, none of this would make sense. Sometimes a shortcut is acceptable.

Thank you for the kind words about the graphics. Still, I think improvement is needed.

aldriq: I think China WILL be a different place when it comes to interacting with the world. As for the Yuan and the Han autonomy - I think the Mongols to be honest made the best attempt at governance in China. Look at their record in other settled societies.

Korea got a mention because I postponed the fall of Guryeo in favour of Choson; Japan is largely the same as historically, I think, so it won't be getting its own chapter.

Thanks all!

Now onto the announcement: there will be no updates within the next two weeks and a bit. RGB is going to Barcelona for a short time. I haven't been there since 92 and I'm very excited, actually.

See you all later!

ComradeOm: it's not only condensed, it's at times simplified. However, that could not be avoided. Yuan politics were intense to say the least; Zhu not coming to power to me opens up possibilities in China, yes, and I was aiming at that conclusion with the many many small changes I introduced to an otherwise very similar history. Han Lin'er isn't really the prime mover in Song, Liu Futong is. Does that bode well for the Song? I don't know

enewald: A great question and one that almost blindsided me, except of course I actually did have an answer when I set to writing this. So I dug it up.

Thing was, the northern Red Turbans were the more powerful and the more populist faction even historically, and Zhu only rescued/captured Han Lin'er when the Yuan defeated Liu Futong. Moreover he left him alive until he could deal with Chen and later Zhang. It didn't quite happen that way here. Chen wasted too many men fighting to the west and is more cautious towards Zhu (Zhu's strategy was one of caution and relied on Chen overcommiting); Zhang is still around. Zhu has a lot to worry about. Meanwhile, Liu Futong simply ground down the Yuan who were continuously weakening since the floods of the 1340s. Having everything happen much later really helps that way; I think continuous victories for Red Turbans would win more zealots to their cause.

Now that Zhu has realised that he overwaited the window of opportunity and Liu has captured true Imperial legitimacy for Han Lin'er, he will probably...well. Wait more. He's got more to lose by attacking than by waiting, and the Song themselves probably cannot really enforce their will in the South. Zhang is likewise a wait-and-see guy; Chen is the aggressive one, but he is in no position to threaten too much, so much so that he has to informally ally with the Mongols just to keep his lands in the West safe.

Calipah: I thought you might enjoy it with Fujian; and the Chingisids aren't completely out of the picture yet, though the Imperial period may well be over. Islam may also play a larger role, or at least a more public one, in southern China.

asd21539: Thank you! I hope to deliver more unexpected good stuff in the future, but the future, being the future, is ever uncertain.

Iwanow: China has a profusion of religions held by the different warlords. At the time of upheaval, many that were hidden are actively striving for a chance to improve their fortunes. Fujian is ruled by a mostly-Muslim alliance of Semu and former Imperial army commanders of Han origin. Xia ruled by Ming (in Sichuan/Guanxi) is the Manichean branch of the White Lotus movement. Song themselves are White Lotus buddhists, but they may have to moderate the populist message if they mean to rule. Basalwarmi and the rulers of Yuan are very firmly Tibetan Buddhists, but their population is mixed.

The strong warlord states along the Yangtzi, however, are more traditional, with Confucian ideals overpowering their former Red Turban allegiance. Zhu, Zhang, Feng and Chen Youlian would probably revert to traditional Chinese ideology if they take power, as historically the Ming did (keeping only the dynasty name of the entire Red Turban background).

Yes, China is certainly pretty interesting; but that's almost historical. What isn't is the timeframe shift and the greater likelihood of these factions surviving in the medium to long term.

General_BT: heh. No *Hongwu is a double-edged blessing. He won't be on hand to Confucianise the economy and destroy the currency, but then the Song are far more radical and who knows what they may do? One thing remains for sure: as long as the Song don't take South China firmly in hand, the Semu may well do better than historically and thus keep China engaged to the wider world to a greater extent. On the other hand, that does mean continued political instability.

And yes, without the historical characters being themselves, none of this would make sense. Sometimes a shortcut is acceptable.

Thank you for the kind words about the graphics. Still, I think improvement is needed.

aldriq: I think China WILL be a different place when it comes to interacting with the world. As for the Yuan and the Han autonomy - I think the Mongols to be honest made the best attempt at governance in China. Look at their record in other settled societies.

Korea got a mention because I postponed the fall of Guryeo in favour of Choson; Japan is largely the same as historically, I think, so it won't be getting its own chapter.

Thanks all!

Now onto the announcement: there will be no updates within the next two weeks and a bit. RGB is going to Barcelona for a short time. I haven't been there since 92 and I'm very excited, actually.

See you all later!

Last edited:

Just when I notice that this has updated again, you say you're going away. Typical. Ah well, have fun in Barcelona. I was there just 1 1/2 years ago. Be sure to look at the progress on the Sagrada Familia. Or at least, that's among the things I'd do, but I guess I just find such large-scale building projects interesting. As Deamon above me said, it's a great city.