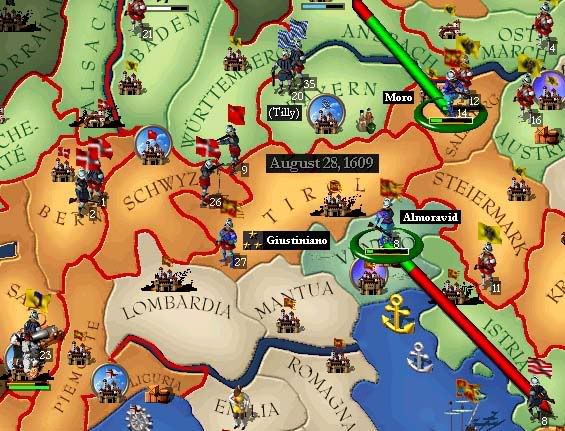

In our war against Bavaria, I have given command of our army in Lombardia to General Pompeo Giustiniano (3, 5, 2, 1 with our DPs) in January 1609. I already outlined my strategy to the Senate. Since Bavaria is small and is focused in Tirol, I have decided to kill her soldiers by attrition, as the Bavarian army is under command of the excellent Flemish General Johan Tserclaes Tilly (3, 4, 5, 1), also known as "the butcher of Magdeburg", famous killer of Protestant Bohemians and Swedes, and we would not win a single battle against him. However I believe I can kill more Germans by attrition, than the limited resources of Bavaria can replace. We will just have to achieve a total victory over our enemy, and I count on Savoy for that.

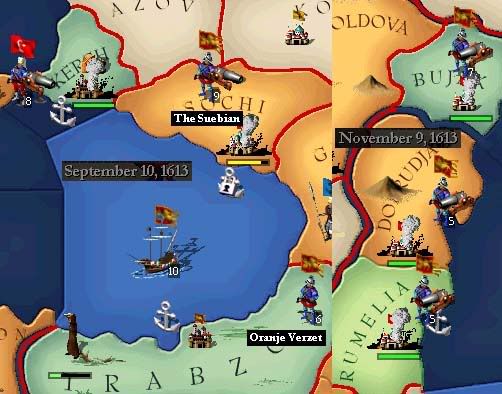

Every two months Giustiniano pays a visit to Tilly and about 5,000 Bavarians die of attrition while our forces retreat. Giustiniano makes sure that the total number of troops in Tirol is not over 45,000, our support limit. Bavaria has to build troops all the time, and will soon run out of funds. Already in June Savoy has conquered Alsace, and while Bavaria tries to attack Lombardia, I send Colonel Moro through Austrian lands to surprise the Bavarian rearguard.

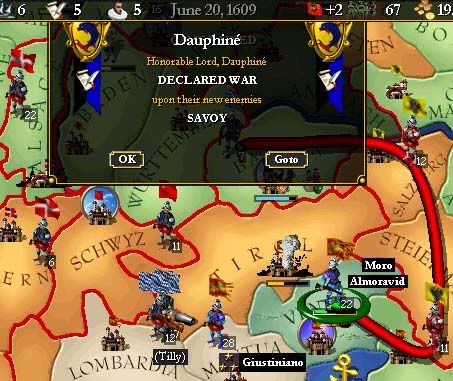

But suddenly Dauphiné, Hungary and Switzerland decide to declare war on Savoy and Jerusalem. We are forced to join in the fight out of loyalty, but our situation becomes very compromised. We are at war with three of our neighbours. Finishing Bavaria is still our priority, and just in time, our finantial effort in researching new weaponry produces a significant advance (level 18) and our troops become much more eficient in combat than our enemies. Tilly is still a headache, but the Hungarians melt like cheese in a fondue when they try to overcome the much smaller army of Almoravid.

But for Savoy things are not looking bright. The Swiss defend the passes to their mountains fiercely, and the French army of the Dauphin sieges their capital. Meanwhile Moro arrives to the Danube and waits until Ansbach is undefended. The summer is dying but the war against Dauphiné's alliance does not allow for any delays. If winter comes and the snow covers Ansbach we will pay a dear price in Venetian lives. Moro establishes his camp at the North Bank of the Danube and defeats several attempts to dislodge the siege. The Bavarians invade the plains of Lombardia, but are met with deadly force even if the army of Giustiniano suffers grievous loses. The Bavarians claim the battle as their victory, since Giustiniano had to retire to Mantua, but Tilly also suffered tremendous loses, and his small army is completely routed by the Savoyards, while attempting to reach Alsace. Tilly ends his career in the Alps of Bern. A great loss for Bavaria, as Tilly was so young and had a long and promising career ahead of him.

Troops are needed everywhere. Moro needs reinforcements to sustain the siege of Ansbach, Almoravid resists the Hungarian attacks, but is dangerously low on troops, and requests reinforcements to invade Hungary. Giustiniano has to make good the loses suffered at the hands of Tilly. We call to arms everybody born between 1580 and 1588, then those born between 1588 and 1590. The Venetian recruitment system consists in making groups of six men. They chose between themselves who goes to war, and the other five pay for his equipment, sustainment and even support his family if he has dependants. It is a good system when we need few soldiers, but it is ineffective when we reach the bottom of the bucket. Calling for the second soldier in the group is perhaps too much to ask from them.

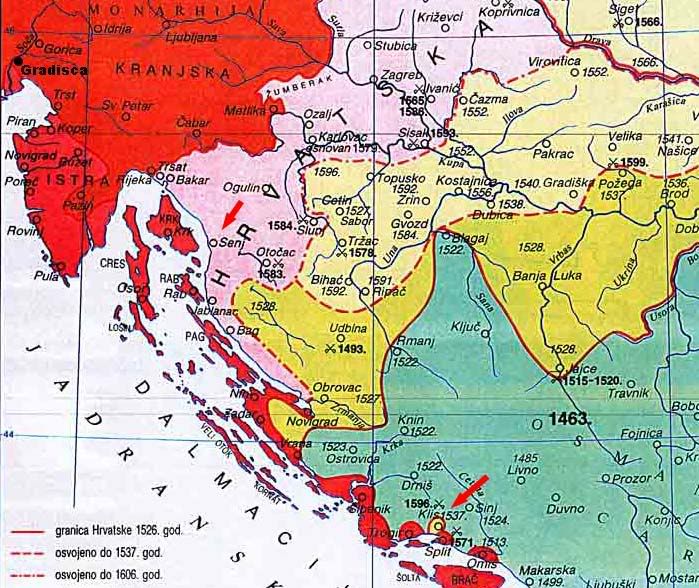

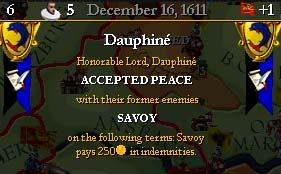

But Bavaria has even worse problems than we do. By the next summer (1610), of the 60,000 soldiers of the once proud Bavarian army, and despite the intensive recruitment only 25,000 are left. Maximilian of Bavaria starts to be more reasonable in his peace offers, and since Charles Emmanuel is having a rough time, Maximilian gets his offer of 54[,000] ducats to Savoy in exchange for the return of Alsace to Bavaria accepted. Savoy is now out of the war, and our warscore is terrible despite our great estrategic position. We will need to occupy every Bavarian province, including Alsace to meet our goals. Damned Charles Emmanuel. Meanwhile Almoravid sends Colonel Roberto Contarini to besiege Krein, while he defends Istria and Dalmatia.

By the end of 1610, the Bavarian armies had finally been destroyed, and Moro conquers Ansbach. Just when one enemy is being defeated, another takes the torch. The armies of Dauphiné finally conquer Savoie unmolested, and cross the Alps invading Piamonte.

A new army is recruited hastily in Lombardia, and Giustiniano leaves the siege of Bayern in the hands of Moro, and in a surprise attack routes the forces of the Dauphin. Giustiniano leads his army directly to Dauphiné, with the goal of knocking them out of the war. Almoravid's regiment is destroyed by a large Hungarian army that runs through the North of Italy towards the French Alps, looting our countriside in their path.

But once Dauphiné is under siege, and Roberto Contarini conquers Krain, and heads towards Pest, the capital of Hungary, it looks like we are soon going to win this war. Once again Charles Emmanuel I "The Great" of Savoy throws our effort through the window, and agrees to pay 250[,000] ducats to return to status quo. Double damned Charles Emmanuel. With friends like that, who needs enemies? We have to pay one third of that amount, 83[,000] ducats. Next time we are leaving Savoy out in the cold.

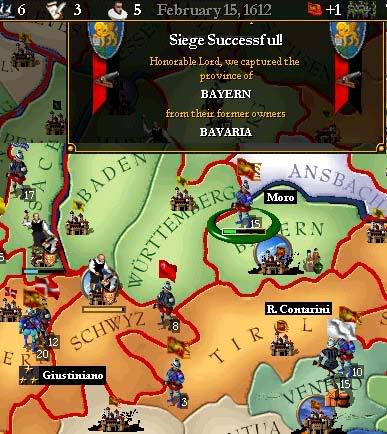

But we are still at war against Maximilian Wittelbach of Bavaria. Giustiniano is sent from Dauphiné to Alsace, and Moro conquers Bayern.

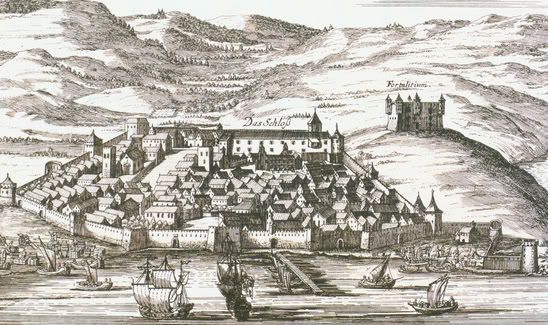

Maximilian escapes towards Alsace to continue the resistance, but resistance is futile. Without Tilly, Giustiniano is king of the hill, and makes good work of the last Bavarians. The siege of Alsace goes slowly. It has already been 5 years of war, and the Signorie is anxious of starting the Indian campaign. When November arrives, Giustiniano decides to launch a full assault before the first snow. Our soldiers are able to overcome the defenders, and enter the city through the breach in the walls. Victory. Maximilian surrenders without terms. He finds the conditions of the Signoria extremely generous. He will have to yield access to Venice armies at all times in Bavaria, and will be obliged to pay 100[,000] ducats in war indemnities. Half of that amount to the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

I have ordered the recruitment of native auxiliaries in Kerala, forming a Gurka regiment, and ships have been built in Nile, increasing the size of our Red Sea Squadron, even during our hostilities in the Alps. I will move some regiments to Egypt, and start transporting troops to India. We will soon be ready for our Indian campaign.

Capitano Generale Fodoroni

Last edited: