British Parliamentary style, I filibuster this motion, and keep it from coming into effect.Densely, you are henceforth forbidden to make the Conservatives look bad.

A Biography of Great Men – A History of Britain: 1836-1935 [HoD 3.03]

- Thread starter DensleyBlair

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Don't you mean American Tea Party style?British Parliamentary style, I filibuster this motion, and keep it from coming into effect.

While a perfectly valid tactic, I feel British style filibustering will be more appropriate. (This AAR has the effect on me of making me think I am talking like a British gentleman...)Don't you mean American Tea Party style?

Point taken. Can't really see Newt Gingrich filibustering in Britain, anyhow.While a perfectly valid tactic, I feel British style filibustering will be more appropriate. (This AAR has the effect on me of making me think I am talking like a British gentleman...)

Densely, you are henceforth forbidden to make the Conservatives look bad.

Believe me, I won't need to.

British Parliamentary style, I filibuster this motion, and keep it from coming into effect.

Don't you mean American Tea Party style?

While a perfectly valid tactic, I feel British style filibustering will be more appropriate. (This AAR has the effect on me of making me think I am talking like a British gentleman...)

Point taken. Can't really see Newt Gingrich filibustering in Britain, anyhow.

The all-time longest speech in the Commons, although it wasn't actually a filibuster, was six hours in duration, a record set by the Lord Brougham and Vaux in 1828. So far, you've managed eight minutes.

Well this is great, really great. Though a split in the Conservative will be fun story wise (if it happens), for alt-history a Tory Party run by Gladstone would be very interesting. Either way I'm sure you'll make it fun.

Really, only six hours? Us hangs to like 20!The all-time longest speech in the Commons, although it wasn't actually a filibuster, was six hours in duration, a record set by the Lord Brougham and Vaux in 1828. So far, you've managed eight minutes.

Well this is great, really great. Though a split in the Conservative will be fun story wise (if it happens), for alt-history a Tory Party run by Gladstone would be very interesting. Either way I'm sure you'll make it fun.

I always enjoy having new faces pop up – great that you've joined us, Dr. Gonzo! Glad you're enjoying things.

Gladstone running the Tories would certainly be an intersting twist. I think I'll have to see where the game and the story take his poltical beliefs before committing. Without giving anything away, I'm not sure it's too likely, but there's always the possibility.

Really, only six hours? Us hangs to like 20!

Well, there was an eleven hour speech by an MP during the committee stage of the British Telecoms Bill, though the speaker was able to take breaks to eat as he was not in the Commons at the time. We also have Gyles Brandreth, a former MP and endearingly eccentric personality, who formerly held the world record for the longest after-dinner speech, which clocked in at twelve and a half hours, but it wasn't parliamentary in nature.

I've just finished a bespoke map for the next update, which I'm very pleased with. I'll be uploading the rest of the pictures at varying points during the week whenever I get the chance, so I should be on-track for an update some time over the weekend.

America still has longer filibusters! I would say that is awesome, except long filibusters have always been trying to stop good things, like civil rights... Still, I would much prefer a British filibuster, because apparently I can eat! (American filibusters are like torture...)Well, there was an eleven hour speech by an MP during the committee stage of the British Telecoms Bill, though the speaker was able to take breaks to eat as he was not in the Commons at the time. We also have Gyles Brandreth, a former MP and endearingly eccentric personality, who formerly held the world record for the longest after-dinner speech, which clocked in at twelve and a half hours, but it wasn't parliamentary in nature.

1. 'MRICA! WE GOT HUGE FILIBUSTERS! WOOOH!The all-time longest speech in the Commons, although it wasn't actually a filibuster, was six hours in duration, a record set by the Lord Brougham and Vaux in 1828. So far, you've managed eight minutes.

2. But that is Great Britain. This is Internetland. Riddle me that, good sir.

America still has longer filibusters! I would say that is awesome, except long filibusters have always been trying to stop good things, like civil rights... Still, I would much prefer a British filibuster, because apparently I can eat! (American filibusters are like torture...)

You can't eat in the Commons, actually, so you might want to cancel any plans to travel here specially. The speech took place during a special all night committee. There have previously been beds put out in the Lords, though – again, during a very long speech.

Relevant pictures are coming gradually, so I'm still confident of updating at the weekend. See you all then!

Wow! This looks like a nice AAR! I shall stay tuned!Good Luck!

Thanks Duck_Army! And might I also add that I'm especially flattered that you used your first post to say so. Hoepfully you'll continue to enjoy the show.

Update incoming. Stay tuned.

A War At Home and Abroad

Despite Peel's election and the Conservatives' new foothold in government, the mood in Westminster was notably sober during the new administration's first few days and weeks. At first glance, there were certainly no glaring worries for Peel's cabinet. Indeed, Henry Goulburn was running a healthy surplus in the budget, which passed the Commons with relative ease, while foreign diplomacy continued smoothly. Though optimism certainly existed amongst the new elite of Parliament – the Tory front bench – the Commons certainly remained subdued. The mood amongst the People – at this point in time still an altogether frightful phrase, reminiscent of mob violence and the dramatic overthrowing of all upheld order – was especially, and uncharacteristically, quiet. Many, in particular those without the vote, felt that they had been cheated in the elections. Melbourne and his wild, runaway stagecoach of reform had been set to take to the road with not a care for any turnpikes or toll gates it encountered, promising a better Britain for all – or, if not all, then a lot closer to all than at the present. Instead, Peel – notoriously cool about the idea of Reform in general – now occupied Number Ten. Nothing was malicious yet, but there certainly existed, under all of the sobriety, tones of discontent. In a situation alarmingly similar to that of '32 – for the new Tory government, at least – it appeared that Peel's term might not be as smooth as many in the Clubs Carlton and Conservative had hoped. And in a painfully irony, very few of these people were aware of the lurking danger. Indeed, by August, it was estimated that nearly half a million people had joined, or were affiliated with, popular reform societies and groups promoting further electoral reform. Though peaceful societies, such as the still-active Birmingham Political Union,[1] vital in securing the passage of the Great Reform Bill nearly a decade earlier, one could not deny that, again, in another parallel to the mood a decade earlier, the potential for confrontation was present. Nevertheless, Peel pressed on with business blithely unaware of this fact.

Abroad

Britain and her East India Company had long had a history of meddling in the affairs of small Indian states, and Peel was in no mind to see this arrangement come to an end. Sindh had up until 1840 enjoyed freedom from British rule, though the two nations had enjoyed trading links and amicable relations. When it was reported that the Sindhi Mir[2], Sher Muhammad Talpur, was training a force of men for incursions into the surrounding states – all of which were under British control, the government in London responded decisively, relishing the chance to extend Britain's territory on the Subcontinent. War was declared on the 21st August, with General Frederick Lyons, a competent commander who had thus far enjoyed a career based largely on his ability to put down small revolts on the Subcontinent, was dispatched with the Dehli Army – a force numbering just shy of 30 thousand, deemed sufficient for the prosecution of the war in its entirety – to Ahmedabad post haste. Peel's timing could not have been worse.

War was declared on August 21st 1840, just 52 days into Peel's administration.

Only nine days after Lyons was dispatched to Ahmedabad, London was hit by an outbreak of influenza, disrupting all governmental business as Parliament's focus turned to looking for ways to allay the effects of the virus. The Sindhi War, fought five thousand miles from Westminster by foreigners against foreigners, did not sit in the front of many people's minds, and, far from congratulating each other on how grand and prestigious Britain was – as was Peel's plan, the war largely being a show of self-aggrandisement designed to let the Conservatives make their mark on a decidedly Whig-sympathetic nation – the great and good of Parliament instead busied themselves with stopping the spread of disease, or, at the very least, ensuring that the virus wouldn't spread into the confines of the Palace of Westiminster – until recently a very cramped and claustrophobic centre of contagion and with a high-susceptibility to the spread of various mild maladies. Peel's display of might had fallen flat on its face, and his first few months in office had proved to be less than auspicious.

Nonetheless, the war continued in earnest, with the Delhi Army reaching Ahmedabad, a British-controlled city in the province of Gujarat, on October 19th. Lyons was met by a force of around 20 thousand Sindhi troops, who had gone on the offensive under the command of Morad Ali Bhatti. The native forces were wholly outmatched on every front, and Lyons was able to make easy work of the battle. Of the initial 20 thousand, only around six thousand Sindhi troops survived. Lyons, meanwhile, took losses of just under that figure. Ali Bhatti had certainly not proven to be a pushover, but with the technological and tactical advantage, there was no question that the day would go to the attackers. The Sindhi commander managed to give the order to retreat, and his force sped south west towards Rajkat. Lyons gave the order to pursue the enemy, catching up with the remains of the Sindhi forces on November 6th. The ensuing battle was another walkover for Lyons, whose forces had no difficulty in carrying the day. In a fit of particular ruthlessness, the general – more used to dealing with native insurrections than formal situations of war – ordered that every Sindhi soldier caught attempting to flee the battlefield be killed. By the conflict's close, not one member of the defending army had been spared.

The battles of Ahmedabad and Rajkat were wholly one-sided affairs, demonstrating just how little a chance the native forces held against the British.

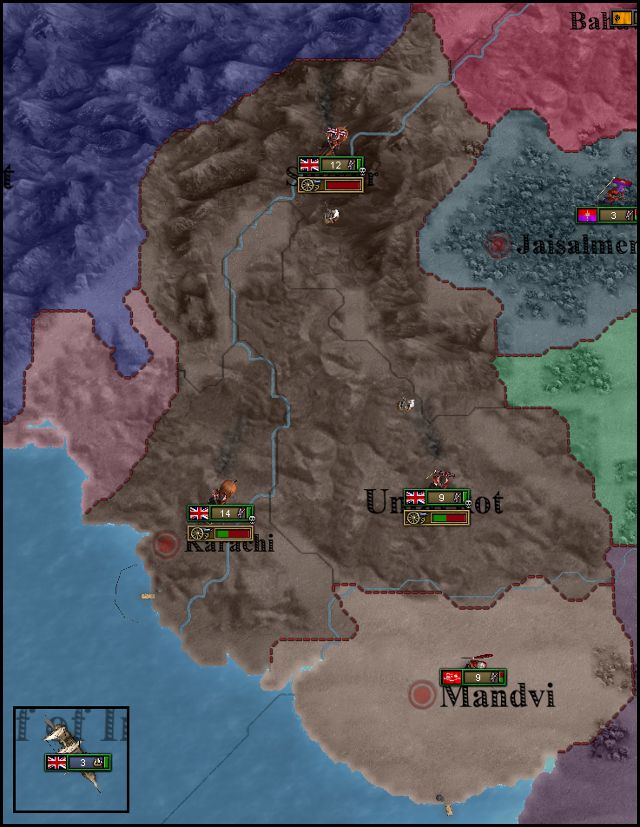

Lyons next marched his army north to Umarkot, where he dispatched nine thousand men to siege the city under the command of Colonel Charles Napier, a veteran commander of the Peninsular War who had been serving in England until only a few months before the outbreak of war.[3] Lyons himself marched on to Karachi, while the 1st Ahmedabad Division under General Edmund Campbell – numbering 12 thousand men – were dispatched and sent to siege Sukkur in the north. To supplement this force, three frigates – HMS Valiant, HMS Portland and HMS Winchester – were sailed from Ceylon to blockade the Sindhi ports.

The situation by the end of 1840. Napier and his portion of the Delhi Army were stationed in Umarkot, while Lyons and the main bulk of the force attacked the capital in Karachi. General Edmund Campbell and the 1st Ahmedabed Division stood ready to attack the northern province of Sukkur.

At Home

The new year saw the obligatory reshuffling of the House of Lords, with the Whigs achieving a minor gain at the expense of the Tories to give them control of about a third of the House. The biggest news of the month, however, would come – wholly unexpected – a few days after. Lord Melbourne, now 60 years old, had been leading the Whigs – both in the Lords and overall – since 1834, serving twice in the capacity of Prime Minister during that time. With Peel's election, Melbourne was faced with the prospect of a maximum spell of seven years in opposition before the next election[4], by which time he would be 67. His predecessor as leader, the venerable Lord Grey, had resigned as Prime Minister for the final time at the age of 70. Melbourne was not made of such sturdy stuff, and now faced with the prospect of no reform – his raison d'être of late – for the next seven years, he was not prepared to wait Peel's government out. On the January 4th, Melbourne delivered his final adress to the Lords: he was retiring with immediate effect, bowing out gracefully in favour of his country home in Melbourne. The news sent shock waves across all of Britain – Queen Victoria herself sending her personal wishes to the man who had become a father she had never had. For the Whigs, the loss was similar. Melbourne had been the paternal figure of the party for nearly a decade, and his absence would be sorely felt by those at Holland House.

Peel, on the other hand, breathed out a sigh of relief when he heard the news. The liberal population of Britain had lost their most prominent, well-respected champion and, more pressingly for the Tories, an ardent reformist. The Whigs were yet to resubmit the Expansion of the Franchise Act to the House, less optimistic after the sobering shock of election night. With Melbourne gone, so too would much of their remaining desire to push through the bill. Without its architect, the Whigs were left without drive, and the Conservatives were able to sleep a little more soundly. Indeed, it seemed as if the people of the United Kingdom had finally come to terms with the prospect of a less ambitious, more Conservative government. Even Ireland, the hotbed of radicalism for the past few years and constant thorn in all politicians' sides, was beginning to calm – a process aided in no small part by the work of a group of influential, anti-liberal Catholic priests who were able to convince many of the "evils" of rash reform. Contrary to the expectations, Britain was actually warming to the idea of a change of tone in national politics. Or so went the theory.

In reality, though it could indeed be said that the populace were, broadly speaking, more accepting of the Conservative administration, in truth this impression was merely a side effect of the inactivity of previously very active radical and reformist organisations. The loud voice of dissent and discontent had been usurped by a more pragmatic tone amongst the protesters. Leading radicals such as Attwood and Joseph Parkes – a less radical figure who had acted as an intermediary between the Radicals and the Whigs during the Reform Crisis – stopped encouraging bank runs and mass demonstrations, and instead focused on the dissemination of pamphlets and philosophical treatises on utilitarianism. Membership of reformist unions and Societies did not diminish, however, and remained healthy. By June 1841, it was claimed by those supportive of reform that there were nearly two million discontented people in the United Kingdom, though active actual figure is unknown.

Not all within Peel's government were wholly oblivious to this fact. The Vice-President of the Board of Trade, though a very junior minister, had held a keen interest in electoral reform since the Reform Crisis, and delivered an impassioned speech in the Commons arguing against reform. His name was William Ewart Gladstone. In his eight hour speech, Gladstone outlined suffrage not as a right, but a duty and a privilege, arguing that when voting one must do so with the interests of one's peers in mind. An influx of new voters, often knowing little of politics outside of what the (in Galdstone's view, biased) local unions and societies espoused. Such a voter would not be able to carry out the duty of suffrage to the best of his ability, and therefore giving him the vitw would be detrimental to society as a whole. It was certainly a convincing argument, and Gladstone soon became a leading anti-reformist figure, noted for his oratory skill and sharp, sober eloquence. As Conservative sympathy swelled in Britain, so did the young Minister's star start it's assent.

In the wake of Gladstone's speech, the Home Office under Sir James Graham, Bt. launched an Investiagtion into the true extent of the membership of the various reformist societies so as to fully understand whether or not there was any real danger to the nation's stability. Delivering his findings to the Commons in September, Graham stated that, contrary to the "positively outlandish" claims of the societies themselves, membership stood at around only 70 thousand, dismissing the biased estimates of nearly two million as "nonsense on stilts".[5] In a worst-case scenario, he revealed, about half of that would be able to be called upon to fight for reform. This idea of fighting for reform was an alarming realisation for the Conservatives, who had hitherto shrugged off any predictions of violence as inflammatory hokum. Not since the Reform Crisis had the fear of revolution been mooted, and it seemed as if it was a possibility as rooted in history as the Norman Invasion – and no one in Parliament had any worries about the French.

Ending the War

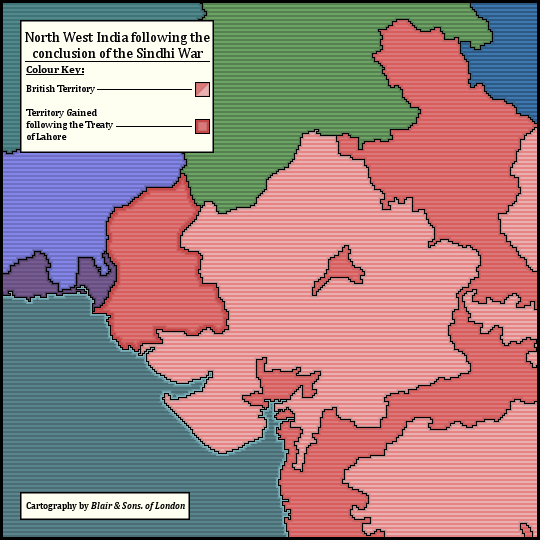

By early October, the war in Sindh, or "Peel's Folly", as it had become known – a lavish show of political prestidigitation – had drawn itself to a close. Napier and Lyons had held control of Umarkot and Karachi, respectively, for over a month, while Campbell had just overseen the completion of the siege of Sukkur. The Mir and his generals had long since surrendered, and had been waiting for the British to formalise their dominance in the region for weeks when, on October 3rd, Lyons and his staff invited them to peace negotiations in Lahore – a city in neighbouring Punjab, a neutral location for the talks. Terms were quickly agreed and ratified in what would become the Treaty of Lahore – the Talpur Mir would abdicate in favour of a British Governor-General, while control of the region would go to the East India Company. The task of informing Westminster of the developments fell to Napier, who simply sent a single worded telegram. The following week, Lord Aberdeen received the missive, no doubt with a wry smile. "Peccavi", it read; "I have sinned".[6]

A map detailing north western India following the Sindhi War. The signing of peace on October 3rd 1841 saw the end of nearly two years of hostilities.

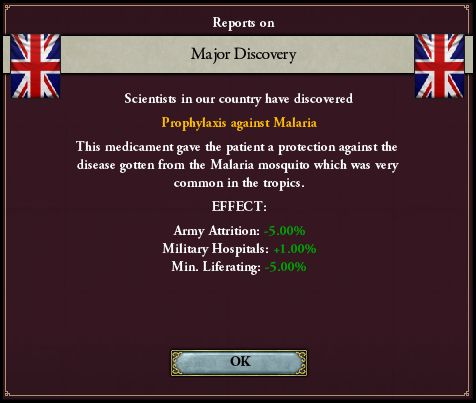

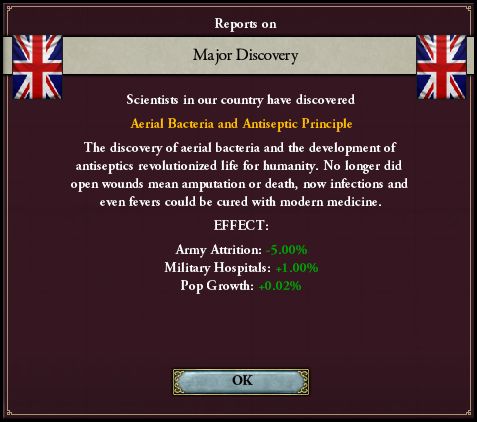

With the cessation of hostilities, Peel was once again able to turn his attention to the home front. He had weathered nearly two years in office, and as he drew closer to the landmark, it seemed his term was finally beginning to settle into a period of calm. Towards the end of 1841, great advances in medical science were the most noteworthy occurrences, with the discovery of nore efficient methods of prophylaxis for malaria and the development of the antiseptic principle among the most high-profile advances. Britain was, like a middle-aged man finally coming to terms with himself, at last starting to accept a more relaxed, Conservative order – a reputation as an innovator and world leader, a shining beacon of stability in the face of not insignificant discontent. All that remained to be seen was how long this lull would last.

Major medical breakthroughs towards the end of 1841 helped to encourage a feeling of stability in the United Kingdom that had not been felt for a long time. Many also suspected that burgeoning colonial interests in the little-explored lands of Africa and Australia would benefit from these new discoveries.

1: Although the BPU disbanded after the Great Reform Bill's implementation into law, Thomas Attwood had reformed the organisation following the decalration of fresh grievances with the electoral system in 1838, working especially to promote Melbourne's Expansion of the Franchise Act.

2: A title equivalent to the Arabic "Emir".

3: In our timeline, Napier was dispatched to India in 1842, though I didn't feel that it would be appropriate to leave the historical capturer of Sindh out of our war as so moved his appointment forward.

4: Parliament was summoned for a maximum of seven years at a time, though very few ever survived until their mandate expired.

5: With thanks to Mr. Bentham.

6: Whether the historical Napier actually came up with the line himself is a hotly debated topic in some circles, though I thought I'd give him full credit in our timeline.

I like the Peccavi bit, and also the Blair & Sons cartographers.  Obviously an esteemed company, with many great works in their name.

Obviously an esteemed company, with many great works in their name.

I see I have a great deal of reading to do. Until then, Congratulations, Densley! You have won the Weekly AAR Showcase

A really fantastic AAR (and I am kicking myself for not coming here sooner!) Keep up the great work!

Interesting update. Peel has managed to convince the British population his Party wont be bringing back the Stuarts or serfdom so he might have a chance at a strong ministry. Also I feel Napier should be slapped for that pun.

So tension amongst reformers but Peel is maintaining the Empire, good good. You mention Britain being relaxed and mature, well I believe Europe is only a few years from going mental so it'll be fun to see how long that lasts!