The Argus

Two things before we get started here.

First - This AAR will primarily be driven by the characters themselves, and the events they experience will form the heart of the writing. But the events will be created by the decisions of Australia, and any other Allied viewpoints will not be of my creation. Basically - I'll be playing as Australia ingame, but do not intend to restrain their perspective to an Australian one.

Second - The Argus was actually a Melbourne - based newspaper which shut down in 1957. It was formed in 1854, and did indeed experience many of the mentioned events. They were viewed as a very convservative and innovative newspaper. As a bit of (useless) trivia, I'd also point out that it was bought and shut down by Keith Murdoch, in 1957, father of the infamous/famous Rupert Murdoch, and as such a forerunner and founder of the News Ltd empire of today.

Enjoy.

Table of Contents

Prologue (June 20th, 1914 - August 5th, 1914)Prologue I - The Three Reporters on Collins Street

Prologue II - Gearing up for the Big Slog

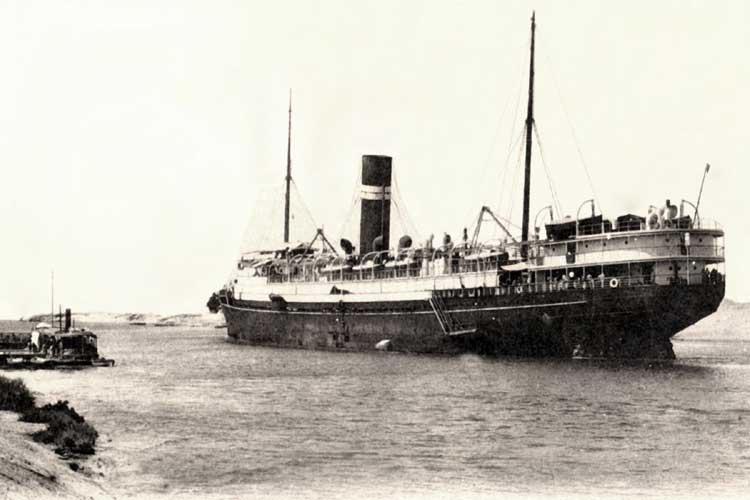

Prologue III - Port Said

Prologue IV - Leaning on the King's shoulder

Part One : The Worker's Government (August 9th, 1914 - September 13th, 1914)

Chapter I - The Right Man for the Job

Chapter II - Stonewall's Mistake

Chapter III - The Minister for Indecisiveness

Chapter IV - An Exotic Adventure

'Perhaps he could be Minister for Indecisiveness?'

Part Two : Innocence's Swansong (July 8th, 1914 - 25th September, 1914)

Chapter I - Au revoir, sweet mirage

Chapter II - The State of the Front

Chapter III - Last Train to Belgium

Chapter IV - Mercy

Chapter V - Fight or Flight?

''You left for the greener grass, my friend.''

Part Three : Mobilizing Spring Street (October 1st, 1914 - November 18th, 1914)

Chapter I - Cocoon of Distance

Chapter II - Where the axe would fall?

Chapter III - The Invasion of Papua New Guinea

"... just for you and me, Ed, you and me..."

Part Four : The War in Asia (November 4th, 1914 - )

Chapter I - 'Nos Morituri Te Salutamus'

____

Prologue - Prologue I - The Three Reporters on Collins Street

The Argus main office on Collins Street, Central Melbourne.

Prologue - Prologue I - The Three Reporters on Collins Street

The Argus main office on Collins Street, Central Melbourne.

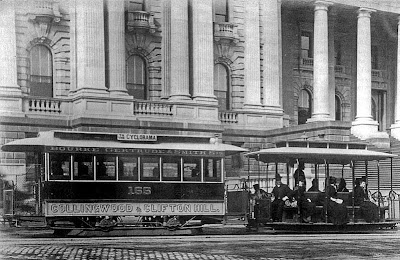

Can you imagine a cold Melbourne night? It bites, it sure does bite. In July, especially, the cold air likes to take a stab at the dead of night. During the day swirls of remaining dew and the still air create a muffled feeling. The dock workers in Geelong watch, as the early morning sun burns through a cold mist, as a large warship chugs by cheerily. The trams running keep the businessmen happy, as they shift through the day's news. Most people, at seven in the morning, are getting ready for the walk to work, kissing goodbye to their families and placing on heavy overcoats.

Today - today was extra cold.

The red hot shrapnel of a searing bomb in Serbia had sliced through the collective, built-up fat of government bureaucracy. Prime Minister Joseph Cook was woken up by the War Minister, informing him his position was about to become very prominent.

In the main office of the Argus in central Melbourne, on Collins Street, James Foveaux was summoning several of his reporters. The office had several rows of desks, all of them full of papers and ink. While some tired writers were quietly discussing events amongst themselves in scattered groups, there was an organised pack to the side. Nearly three desks were separated from the others, and stapled on the walls around them were torn maps and proudly stapled stories. They now turned as Foveaux called them over, and the office watched them disappear into the small meeting room at the front of the room.

He sat them down, amidst a cloud of cigar smoke. The three men were so wildly different it almost boggled Foveaux. Well, he had hired them - but any other editor would have to ask why. That was until they saw their resume - or colleagues.

"You blokes are now in the money. You've struck Ballarat gold, fellas." declared Foveaux with a macabre rumble of laughter, "You've got the biggest news story of your lifetime landing right in yar little laps. And well, I'm bloody jealous." They all exchanged confused looks. The oldest, on the far right, had a mess of shockingly white hair. His bifocal classes slipped a notched as he leant forward and seared the editor with a searching look.

"You're not winding me up, are you, James?" He prodded defensively, still searching. Foveaux shook away his defences, standing up with dramatic energy.

"Look, call me a profiteer, but we've got a big war coming up. Our research division just got word from the boys in London that we've got a Austrian royal gunned down in Serbia. Now, I don't need to explain to you, of all people..." He inclined to the three men, "But, like I said, you blokes have got a war coming up. And I want you lot there when it happens."

Bursting looks of excitement echoed from the three men. Why, the young fella down the end could have cheered, had not Mr. Foveaux been staring down at him. But instead he took a gasp of air and gave a quick nod. Anything more and he'd damn well cheer - blimey, the bloke next to him could've cried.

But, still, decorum.

The shot that lit up Collins Street and Fleet Street.

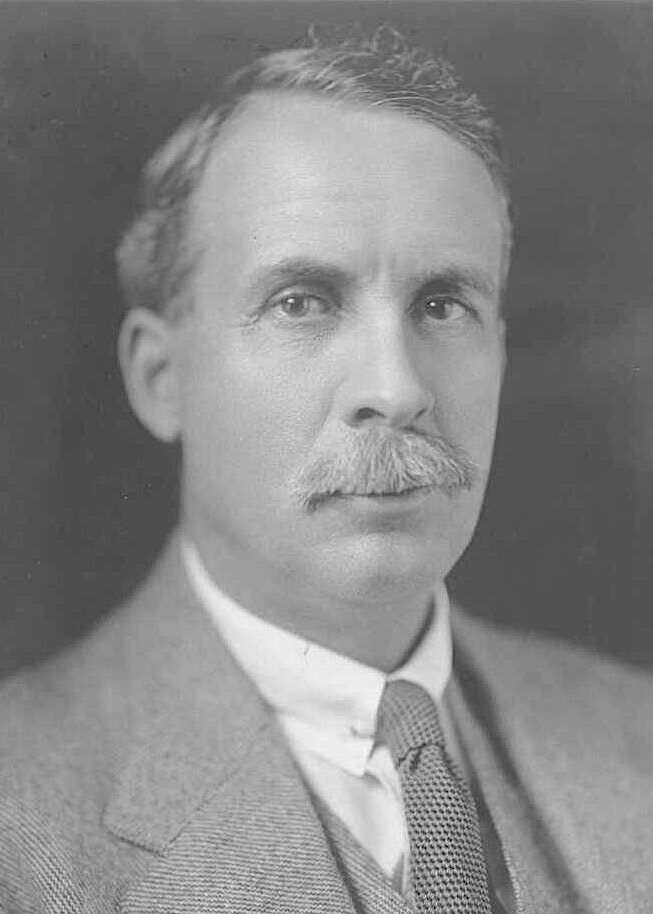

That bloke was Anthony Stonewall. Stoney, as the local reporters affectionately called him, could break down a person faster than the Melbourne inspectors. He could charm the milk out of a cow. He could, well, he could charm Mr. Foveaux, who was a newspaper legend, veteran and tycoon.

Yes, we are forgetting someone. And many never noticed him. Not personally, not at the time. But when he was gone and out, others whispered whether that was Steven Cowell. It was, though. And just like then, he now kept his words to himself.

"Listen, I'm not cut out for that stuff anymore. But you blokes, you blokes still have it. You can still make this news into something. Bugger it, I'm paying you for it! But I want you bastards, you lucky bastards, to get over there and report the hell out o' this story. " confided Foveaux, looking at them with a grin wider than the Nullabor. What was some war to these men? Foveaux had made his fortune riding along the plains of South Africa with the Welsh lancers. He'd seen a fair amount of young men cut down by a Boer's bullet. His father himself had handled his own musket while the Indians cut down comrades nothing on a few yards away, back in '57.

Had Foveaux really seen it happen?

None could doubt his dashing stories of death and glory which seemed to hang on well to the tune of 'Britannia Rules the Waves'. To doubt this man's very character would be a crime on any fine soul. But, that same character was tainted with a exploiters glee like none other. It made Steven Cowell shift with a sense of incoming fear. It even made Stoney give a second glance at the tycoon who wrapped Melbourne round his pinkey - and give a good crack at Sydney, if he tried harder.

The young fella piped up at the end. Edward Gale was that rearing young bloke who gave his peers a slap in professionalism and sure did challenge his older colleagues. He'd earnt a fine wrap from the Richmond police force, reporting crimes with a passion none had seen. Now, Foveaux was counting on him like a young horse at the Cup.

"Sir, so you're posting us all over there?" Wondered Gale, and his innocent question was a good one. They'd be the first to admit their surprise when Foveaux nodded fervently.

"Sure am, Gale. Not all at once, mind you. But I want you three right next to the bloody Emperor next time. Let me clarify it a bit more. I'm sendin' Cowell over to London tonight. Yep, pack it all, Cowell. Yar got a ship waitin' down at Geelong and you got Asquith waitin' at Portsmouth for yar." Cowell didn't looked shocked. He had held off on a family for some... few decades, at least until this whole reporting thing ever died down. One day, though, he'd take a stop up at Bendigo, take a breather.

No one was taking any breathers today.

"Stonewall, yar goin' up over to Carlton. Least 'till this all dies down a bit. I want you attached to the War Office and reportin' on where we're deploying, and what the headmaster is up to."

"Sounds bloody good, boss. Give them a second opinion on sparkin' up any wars, here on out." boomed Stoney, crumbling with laughter. But, look, you could've painted the disappointment seeping across Gale's face.

"Gale, your on hold f'r now. But, and there is no exception to this one, I'm getting you over to Berlin by August. I reckon the Kaiser has as much to say that the King does."

Now it all stopped for a second. They knew what to do now, didn't they just? Maybe it was time everyone leant back and had a think about what was going on. Mr. Foveaux thought they'd hit a few pounds of hard gold, but any day now and the actual diggers themselves could be packing up an heading out. Stoney might as well report on the draft now, before the Kaiser gave the bottle a good shake in Europe and everyone was drunk on jingo. Hell, all these blokes sitting here had grown up with the worst news being of a bit of a fight over in France a few years back. Edward Gale was hardly old enough to remember when the fellas marched off down through Burke Street fourteen years back to fight for Queen Victoria over in Africa. Now Mr. Foveaux was claiming he had seen that pot of gold, and that his one damned shot fired was a bright, blimey, flaming bursting rainbow. You know, that they'd seen nothing but peace and the wealth of an era which hadn't been burdened with death, destruction and the morbid lessons of a great war, and that wealth had damn well already cursed them into a spirit of drunk jingoism.

Couldn't fool Cowell though.

He gave Stoney and Gale a wave as they slipped out, before turning back to Foveaux with a depressed look which was weighed down with guilt carried over many a year.

"You can't blame me for this one, Steven. You can see that we've got the biggest piece since Federation, or when the bloody workers got their own say. There is a story over there, and you're the best shovel to dig it all up, the Argus 'as got." Cowell wasn't buying this one, though. He wanted his own say and the editor was going to listen.

"Look, I'm not naive about this stuff. I've been with the diggers with the Boxer thing, I reported with you in South Africa! You know me, James. And you bloody know what we've seen. And I, I just got this feelin' 'bout this one." He finished lamely, sitting back and trying to capture that nagging thought. What the hell was he trying to say here?

"What the hell are you saying, Steven?" barked Foveaux, "We've seen more wars then I've seen sun rises. They come dime a dozen, every year we got a new issue. Might be the Turks, might be the Chinamen. It all goes away." He promised grandly, pulling up an old map of Europe and grinning at Cowell.

"C'mon, where's your adventure? Ten years ago and you would've been beggin' me to go over." That was true, Cowell couldn't deny it. A small part of him was still cheering at him to go. What are you doing, Steven? It would ask so hurriedly. But there was that other part, that part which questioned whether he'd taken his draw of God's luck and this time, well, it was his time.

"Okay, what if something happens? What if the Kaiser gets touchy and we've got a war on? And don't you bloody deny that, either! 'Cause we've all seen what's been waitin' up in Europe, we all know it's comin'." accused Cowell.

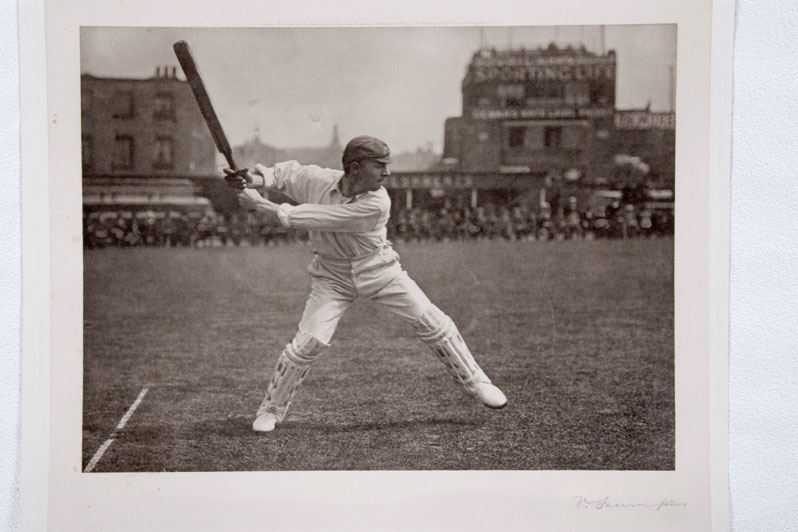

"If somethin' happens..." begun Foveaux, "Then... you'll be there to report it. You can head on over with the troops while I send over Stonewall or Gale. Look, Steven, I need someone in London. The Argus needs to beat the Herald bastards, we need an Australian reporter watchin' things for us colonials. Now, when you get on that boat tonight, you'll be headin' for Singapore. After that, it'll be the Suez and then straight through to London. Meet up with the Times reporters there, but then you'll be keeping tabs on the European innings, eh?" He gave a chuckle, and Cowell did as well.

"If something does happen, Steven," said Foveaux softly, sitting down on his desk and looking at his long time friend, who looked mighty worried, "I would trust no other reporter here with this. Now go and make the Argus the first and best. I trust you to."

Now what could Steven Cowell say?

He'd just been given a warrant to wreak havoc with what he says. While the blokes are back here reporting that the ALP was still crushing the Liberals, or Stoney was hanging on to Cook's every word Steven would be in London, waiting for the executioner's axe to fall. And, well bugger them all, he'd be damned to miss this one.

It really was the story of a lifetime.

"I'll take it, James, and I'll give you the best correspondence yet. I'll go to Europe."

Last edited: