wonderfully grim stuff, nicely hints at an entire society at the brink (or beyond?) of collapse

Lords of France: Roads to the Enlightenment

- Thread starter Merrick Chance'

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Wonderfull update as always. This will no doubt be very bloody. Is the outcome certain yet or is it still anyones game?

Wonderfull update as always. This will no doubt be very bloody. Is the outcome certain yet or is it still anyones game?

So I'm going to be honest here

My computer died a bit more than a week ago. However! I'm not letting that kill this AAR. What I'm going to do is 'play through' some of the peripheral conflicts of the war (which by and large are understandable continuations of trends already present in the AAR), and when my computer gets back I'll try as hard as I can to get up to 1600 with relatively similar European borders (luckily the 40 Years War period is so tumultuous that most changes to minor countries can be explained as a casualty of the war).

Luckily the War of Hispaniola will likely take up the next 1-2 weeks, and that war mainly involves Canada (about which I can make up a lot of stuff because its isolated position makes it a largely 'roleplay'y region), and the decline of Portugal's colonial empire (which was already happening at this point in the game already).

A question: does anyone know of any French Catholic priests (or possible French priests, including theologians and philosophers) of any significance before 1600? I'm planning on having a short introduction on the way that the church developed in Canada (which became an asylum for European Catholics, and thus became a far more important and independent French holding). Matteo Ricci could fit the bill--he was a major Jesuit, and considering that France expanded into Canada far earlier than in OTL (and that European exploration of the East is far slower), it's possible that he could be sent to Canada instead of the east. However, I don't see Ricci, an Italian, becoming powerful in Canada without a significant conflict with the crown, which isn't what I'm going for just yet.

well considering this is Alt. History you could just make someone up. Its what I did. Im certain you could make it work.

St. Francis Xavier (1506-1552), from Spanish Navarre; his parents could theoretically have emigrated to French Navarre. Also Xavier's French roommate at the University of Paris, "Blessed" Peter Faber (1506-1546). There are a lot of notable Jesuits in the mid-16th century.

EDIT: If you need guys from the latter half of the 16th century, the Wikipedia category "16th century French Jesuits" has about a dozen theologians and scholars in it.

EDIT: If you need guys from the latter half of the 16th century, the Wikipedia category "16th century French Jesuits" has about a dozen theologians and scholars in it.

Last edited:

From that description, I only know one Portuguese Jesuit - Father Fernão Cardim (1549-1625). I do not know much about him, but from what I know, he was a priest sent to the Jesuit mission in Brazil. He is known for his documentation of the Brazilian flora and fauna (not sure), as well as for being one of the teachers of Father António Vieira (also a Jesuit priest whose sermons influenced Portuguese literature).

EDIT: I found this web page in Portuguese about Father Fernão Cardim. I am sorry for not finding any information about thus man in English.

Great to hear from you Chris!!! What happened to your AAR? It was so fantastic!!!

EDIT: I found this web page in Portuguese about Father Fernão Cardim. I am sorry for not finding any information about thus man in English.

St. Francis Xavier (1506-1552), from Spanish Navarre; his parents could theoretically have emigrated to French Navarre. Also Xavier's French roommate at the University of Paris, "Blessed" Peter Faber (1506-1546). There are a lot of notable Jesuits in the mid-16th century.

EDIT: If you need guys from the latter half of the 16th century, the Wikipedia category "16th century French Jesuits" has about a dozen theologians and scholars in it.

Great to hear from you Chris!!! What happened to your AAR? It was so fantastic!!!

Last edited:

Great to hear from you Chris!!! What happened to your AAR? It was so fantastic!!!

I don't want to threadjack attention away from Merrick's own excellent AAR; the short version is that real life got in the way (as it sometimes does), but that I expect to update before the end of the month.

Merrick, it's a shame about the computer glitches (no saves survived?). I am sure that difficulties notwithstanding, you will find a way to weave it together into a compelling alternative history.

My god, it's Chris Taylor! Thanks for posting!

Firstly, given your tip I found the perfect man for the job of attempting to turn Quebec into a Bishopric.

Secondly, I'm psyched to see the way that your AAR develops.

And thirdly, I've somehow gone my whole life without learning to do backups. I'll probably start now (no time like the present, and starting Grad school with this rink-a-dink netbook is killing me), but yeah, no saved games. Thanks for the encouragement, and I'll probably post a new entry within the week!

Firstly, given your tip I found the perfect man for the job of attempting to turn Quebec into a Bishopric.

Secondly, I'm psyched to see the way that your AAR develops.

And thirdly, I've somehow gone my whole life without learning to do backups. I'll probably start now (no time like the present, and starting Grad school with this rink-a-dink netbook is killing me), but yeah, no saved games. Thanks for the encouragement, and I'll probably post a new entry within the week!

Last edited:

Having just finished reading this..... All I can say is very, very well done. Can't wait for the update!

The Bishopric of Quebec

The War of Hispaniola occurred in the final years of the 40 Years War, and represented the expansion of the war into the one place which had been considered safe in the last quarter of the 16th century: the New World. Brasilia, the English colonies, and the Caribbean colonies all became refugee centers, and the colonies grew massively through the 1600s.

The New France colony was one of the few bastions of stability in the Western world during the 40 Years War, and reaped massive benefits from it.

But no colony grew faster than New France, which went from being a backwater to becoming a massive, sprawling colony with a highly multiethnic population. The reason for this is intrinsically tied to the fate of the Catholics of Northern Europe. After the Brabantese Revolt (1), the loss of most Danish territories during the Northern War, the utter failure of the Parliamentarians in the English Civil War (2), and the collapse of the Spanish-supported, Catholic ‘Provincial Governments’ in Northern Germany all led to the expulsion of thousands upon thousands of Catholics from their native lands. Many of those Catholics found refuge in Southern Germany, which was highly depopulated after the war. But a sizable amount (4,500 Germans 4,000 Flemish, 3,500 Scots and 1,400 Danes) found refuge in the New World, and in the New World, most of these refugees of civil war ended up settling in New France, specifically in ‘les trois provences’, or the three least developed southern provinces in New France—Abnaki (which became Nymark after its settlement by Danes), Mikmack (which became Ecosse Nueve after its settlement by Scots), and Epekwitk (which became Neuisle after its settlement by Germans) .

A painting of a neighborhood in the colony of Neuisle. Les Trois Provences, or the colonies occupied mostly by non-French settlers, brought a huge amount of revenue to New France, but also a good deal of discord

This influx of immigrants completely changed the nature of Canada’s economy and culture. What had been a relatively monocultured region turned into a melting pot of Northern European cultures. This societal complexity was further increased by the integration of several American tribes into Canadien society over the 1590s. But the huge increase in New France’s urban population had another effect, which greatly troubled King Louis; that effect was the increasing power of the Jesuits in the New France colony.

One must understand, although Canada remained one of the most homogenously Catholic regions of the world until the 1800s, the kinds of Catholicism practiced by the different peoples of the colony varied wildly.

An etching of the capture and murder of a Catholic Indian by Canadiens. Sectarian conflict was a constant underlying issue in Canada during the 16th and 17th centuries, and though the influence of the Jesuits led to some degree of compromise, lynchings and 'communal murders' weren't a rarity, especially in Les Trois Provinces

Even the differences in religious interpretation between the more religious Canadiens and the more secular Cosmopolitains led to constant struggle, and then throw onto that the differences between Danish, German, Dutch, and Indigenous Catholicism, and Canada started to look completely ungovernable.

But the Jesuits saw this diversity as an opportunity for them. The lack of a common religious language made these monks (who were to a man experts on Catholic theology) the administrators of the New France colony overnight. Pierre Biard in particular went from the local pastor and occasional missionary to the Abnaki tribes to a massively popular regional figure in les trois provences. Biard’s uncompromising view of Catholicism struck a chord with the men and women who had fled Europe in the face of Protestant persecution. This local notoriety turned into region-wide popularity when the town elders of New Glasgow asked for a shared communion. Scottish Catholicism, though unquestionably a denomination of Catholicism, had accepted certain aspects of Protestantism into it, and the shared communion was the most important thing that differentiated Scottish Catholics from Roman Catholicism.

A more tolerant minister would have accepted such a difference. But Biard reacted to the town elder's request by summarily excommunicating the whole village. When he returned to the village two months later, they begged to be brought back into the religious fold--6 members of the village had died in a state of excommunication, which would mean that their souls had gone to hell. It was only after the village accepted the orthodox Catholic practice on communions that Biard rescinded their excommunication. As news of the Excommunication of New Glasgow spread around New France, Biard quickly gained a reputation as a hardliner and, possibly, as the only man who could control the provinces of Canada.

Father Biard in the Maine colony. Biard was famous for his ability to find common ground with both the newly Catholic Indians and the evangelical refugees. His dark charisma and uncompromising attitude made him the perfect man of his time, even in as peaceful a land as New France.

Biard’s massive popularity in the supposedly ungovernable settled provinces put him in exactly the right spot at the right time, because his rise to power occurred in parallel to a movement within the Papacy to create a bishopric within the borders of New France. So in 1601, when Pope Gregor VII forced Louis XII to create the Bishopric of Quebec, Biard was the obvious choice for Bishop. He set out to reach the new capital of the colony, Sacremont, and reached it in the spring of 1602, assuming both the titles of Bishop of Quebec and Vicar-General of the Jesuits in New France.

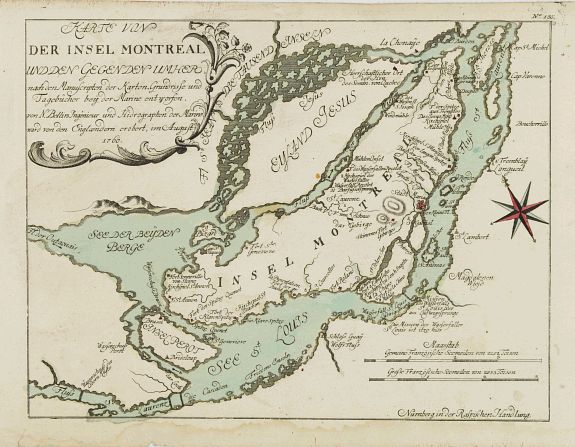

A map of the island of Sacremont, later named Montreal

Sacremont was the perfect example of the rise of Jesuit rule in Quebec. Settled in 1587 by 300 Frenchmen and 270 Dutchmen, the 30 mile long island soon became the center of both the trade and religious aspects of the colony. As Canadiens and Frenchmen moved into the interior to avoid Spanish/Portuguese pirates, and Flemish refugees moved to the colony in search of a more purely Catholic lifestyle, the city of Sacremont (3) grew in just 20 years from a village of 500 to a city of nearly 3,000. The makeup of the city was also unique in the New World, and perhaps in the world as a whole—nearly 20% of the city (or 600) was made up of monks, priests, and friars.

The city was also perhaps the most educated in the world: the Quebec school for boys in, which was created 1598 (and became the University of Quebec under Biard’s watch in 1627) taught literacy in French, Latin, and the Indian languages to any Sacremontese male Catholic. It is estimated that in 1640 Sacremont was the most literate city in the world, with 80% of males and 50% of females being able to read and write at least in French. This educational advance was crucial to Sacremont’s survival because the city’s importance was twofold: it was the stronghold from which both traders and missionaries colonized the Canadian interior.

[

Sacremont University, established in the 1620s, was one of the oldest facilities for higher education in the New World, and remained the only university north of the Rio Grand until the establishment of Harvard in the 18th century

Sacremont University, established in the 1620s, was one of the oldest facilities for higher education in the New World, and remained the only university north of the Rio Grand until the establishment of Harvard in the 18th century

Soon enough, traders and priests were traveling as far inland as the modern state of Michigan, converting and trading with hundreds of different tribes, most importantly the Huron tribe. But trade was unquestionably put behind the necessities of religion. Biard was horrified at the possibility of a conflict on the Saint Othe River (which could possibly lead to the closing of the river by hostile tribes, cutting off the missions in Huronia), and thus forbade settlement further west than Sacremont. He also banned the sale of liquor to Indians, which led to many conflicts between the clerical and mercantile classes throughout the 17th century.

But regardless of these conflict and the many restrictive laws that Biard created in his capacity as Bishop of Quebec, Biard was a massive political player, whose authority rivaled the King’s throughout the colony. From the mixed French-Indian populations of Newfoundland and the northern expanses to the evangelical population of Sacremont to the panEuropean and volatile Trois Provences, Biard’s seemed to be the only person holding the Bishopric of Quebec together.

This very swiftly started affecting the political culture of the region. Priests, not mayors, were the purveyors of laws and regulations. Young Quebecois grew up wanting to become frontiersman-priests, and Canada became the largest producer of Jesuit missionaries through the 17th century. All of this affected the popular culture as well. Quebec saw itself as the City on the Hill, the manifestation of what had been the Catholic dream since the collapse of Charlemagne’s Empire: a panEuropean society living peacefully under Catholic law.

Father La Dassow, the German Jesuit which Biard appointed Vicar Colonel to les Trois Provences. Biard's tendency to disregard ethnicity when picking his delegated was just one of the many issues that king Louis XII had with him

This was a huge threat to Louis XII—in the middle of the longest war in memory, the King saw his only colony slipping away from him. Worse still, the rules against expansion were cutting off what Louis saw as the main avenue of France’s economic expansion postwar—even in 1608 the Saint Omer river valley was one of the biggest investments of the Parisian mercantile class. Worse still, even though Biard was nominally a Gallic Bishop, appointed by the King, there weren’t any obvious replacements. This left the King in a rough position—he needed to find a way to increase his authority in the colonies, but he also needed to do so in a way that wasn’t obviously an affront to the zealous Bishop of Quebec.

And so a Portuguese attack on a French mission in the Bahamas in 1610 gained colossal significance. Although this attack was only the last in a long line of Portuguese attempts to expel the French (and the native allies of the French) from the Caribbean, Louis saw the attack both as a way to make a grab for the defenseless Portuguese colonies in the Caribbean and as a way to station a large contingent of French soldiers in the Bishopric of Quebec. And thus the War of Hispaniola began.

Next: The History of the Portuguese Colonies

1 The revolt, led by Dutch revolutionaries and Flemish evangelists, led to the creation of the Provisional Republic of the Netherlands, which spanned the old provinces of Antwerp, Brabant, Limburg, Breda, and Zeeland. The Republic was fiercely Calvinist, and expelled on grounds of collusion with Imperialists any Catholics who refused to convert.

2 the Parliamentarians have to this day been cast as erstwhile Republicans seeking to create a state similar to what became of the Flemish Netherlands. What is ignored is that this revolt of the non-English periphery against the English center occurred primarily due to religious causes, and that the failure of the Scottish, Welsh, Cornish and Irish rebellions led to mass deportations at the end of the War)

3 This world’s version of Montreal

4 Which had always been known for their ability to accept and tolerate Indian fashions, which was understandable, as the Indian hinterland was their livelihood.

Last edited:

I'm in the middle of reading your update, which is great, and want to suggest a small correction/name change.

In French, tres means "very". Since you're referring to the three multiethnic French colonies, I assume (and pardon me if I'm wrong) that what you really mean is "three" (i.e. trois in French). If they were three Spanish colonies, tres would be right on target.

EDIT: Many nice touches in this update. Sacremont instead of Mont Royal; Jesuits as the "honest brokers" (and power brokers) between the different settlements and ethnicities; and introducing aspects of real-life Pierre Biard (village excommunication etc).

Hopefully Biard and his successors avoid becoming the Catholic version of Puritans; that might lead to all sorts of colonial unpleasantness.

In French, tres means "very". Since you're referring to the three multiethnic French colonies, I assume (and pardon me if I'm wrong) that what you really mean is "three" (i.e. trois in French). If they were three Spanish colonies, tres would be right on target.

EDIT: Many nice touches in this update. Sacremont instead of Mont Royal; Jesuits as the "honest brokers" (and power brokers) between the different settlements and ethnicities; and introducing aspects of real-life Pierre Biard (village excommunication etc).

Hopefully Biard and his successors avoid becoming the Catholic version of Puritans; that might lead to all sorts of colonial unpleasantness.

Last edited:

I'm in the middle of reading your update, which is great, and want to suggest a small correction/name change.

In French, tres means "very". Since you're referring to the three multiethnic French colonies, I assume (and pardon me if I'm wrong) that what you really mean is "three" (i.e. trois in French). If they were three Spanish colonies, tres would be right on target.

Ooof! You're right. It's funny how a year of college Spanish completely infiltrated the knowledge i gained from 7 years of high school French

Nice job! I think we can safely say that grad school has only diminished your quantity, not your quality.

Nice job! I think we can safely say that grad school has only diminished your quantity, not your quality.

Thank you!

So the way I see it is that I'll arrange my presentation of the war by front (as I said), with each section showing a more villainous and depraved France, and a more convulsive and pained Europe. This lets me navigate the complexity of the war (Spanish and French soldiers fought in Switzerland and in the Palatinate, but not on the Pyrenees and were allied in the Caribbean), and gives me (and you, the reader) time to acclimate to the attitudes of the time until the widespread razings of west German cities becomes, if disgusting, understandable; the sections are arranged almost as a descent from earth to hell.

In this section (the War of Hispaniola), we're relatively far from the action, seeing the war from the perspective of the region which (perhaps) benefited most from the war, and we're seeing a war where France is playing a relatively benevolent role. But even here we see sectarian violence, intolerance, and the kind of state which would likely be an active participant in the War's many crimes against humanity if it had the opportunity to.

But as we go further into the war and closer to the main front, we begin to see a France who is ever more tempted to use her overwhelming strength not to force any advantage or to create a more tolerant Europe, but rather to preserve a status quo ante. And we see an increasingly degraded French army acting more and more like a lynch mob.

War of Hispaniola (1610-1614) -> The Dutch Front of the War (including the revolt by the protestant southern Netherlanders) (1575-1595) -> The French War of Religion (1578 -> 1611) -> the Rhenish Campaign (1610 -> 1616)

Last edited:

The Portuguese Caribbean

The Caribbean as of 1600. Note that the Portuguese held, through their alliances with the tribes of the Caribbean islands, nearly all of the approaches to the Gulf of Mexico. However this indirect rule was especially fragile, as evinced by the encroachment of French influence into the Bahamas starting in 1590

Ever since Christobal Colombus landed on what became Cuba in 1496, the Caribbean had been the center of European colonial wealth. Sugar, coffee, liquor and gold flowed from this small island chain into the courts of the Kings of Europe. By 1580, money from Hispaniola alone had accounted for more than a third of Portugal’s treasury, making it a more profitable colony by far than Brasilia or the Kingdom itself. But Hispaniola wasn’t the only Portuguese colony in the Caribbean at the time; in fact it was the center of a veritable empire by 1600, an empire that was on the verge of collapse. This section will discuss the growth of the Portuguese empire in the Caribbean, as well as the factors that led to the colony’s loss in the War of Hispaniola.

Portugual’s colonization of the New World started with the Treaty of Algarve between Spain and Portugal (the two leading naval powers of the time), which divided the Latin American continent into two halves—the Eastern half would be colonized by Portugal, the Western half would be colonized by Spain. This affected Portugal’s early colonization in two key ways:

1. The Caribbean, excluded from the treaty, became the focus of Portuguese efforts in the late 16th century.

2. This colony, as well as the Brasilia colony, was created in the context of a complete lack of military competition from other great powers.

The Caribbean islands were a huge temptation for any colonizing power—its islands were small, rich, and easy to dominate with garrisons; its natives were less militaristic than the native tribes of North America or the kingdoms of the East, and the sea’s position at the mouth of the trans-Atlantic trade routes made it easily accessed from Europe. These factors made the Caribbean the stomping ground of the great colonial powers in the 17th century, but it also made the region easy pickings for the Portuguese colonial empire.

A map of the Brasilia colony, circa 1570. Brazil was largely ignored until the Treaty of Trinidad, after which the colony became the main driver of the ailing Portuguese economy

Growth

The Portuguese model of colonialism was very different than the French, English, or even Spanish model. Unlike the French and the Spanish, the Portuguese deployed relatively few military assets to her colonies—the largest troop concentrations were a 600 man garrison on the tip of northern Brazil and a 1,000 man army deployed in the Caribbean—and unlike the English, who made great pains to homogenize her colonies (leading to a long and arduous war against the Cherokee and Iroquois), the Portuguese were content with using native American forces to do most of the ‘heavy lifting’ of the colonies while the white settlers remained at the head of a complicated administrative hierarchy.

These natives weren’t forced into the Catholic faith, they weren’t asked to learn Portuguese or put into schools. The Portuguese system was a relatively simple one: they traded their manufactured goods for the valuable goods of the New World, and taught the Indians several technological processes (the process of distilling liquor, or of creating molasses, spread rapidly through South America after European contact).

This system worked very well for what it was—Portuguese merchants soon traded across the whole of the West Indies, and this trade system grew into a system of political interdependence once the Portuguese started trading arms to the natives. Best yet, the system required very little actual colonization and imposed few administrative costs—the only actual Portuguese settlements by 1600 in the West Indies were in Hispaniola and Puerto Rico. But from Hispaniola and Maranhao, a network of Portuguese traders, administrators, and plantation owners controlled an area which was larger than Portugal by multiple magnitudes.

Overreach

The Battle of Tunis. In 1590 the largess of the Portuguese treasury had convinced king Manuel IV to embark on a crusade against the Ottoman viceroy in Tunisia. The war was won, but its effects led to Portugal’s massive loss in the West Indies

While the Portuguese system worked well for what it was—a mercantile empire designed with cost effectiveness in mind—its swift success soon overwhelmed the minds of the royal bureaucrats looking west from Lisbon. Letters to Manuel IV and the King’s speeches themselves indicated an increasing level of imperial arrogance, with the widespread belief that Portugal’s trade dominance over the West Indies could be turned into a military dominance, putting Portugal in an advantaged position over Spain, and the thought that wealth from the New World could be used to fund imperial adventures in the Old World.

This imperial arrogance also came from Portugal’s secluded position in the corner of Europe. Without sizable Protestant minorities or any real part to play in Germany’s wars of religion, Manuel IV had spent most of his time growing rich, sending colonists and merchants to the new world, and offering highly profitable loans to the Spaniards. But Manuel was not content with this; he saw that his country was the richest in the known world but that it had little to show for it: its culture was not lauded, its soldiers not prideful, its territories languished in obscurity. So, in 1602, Manuel decided to spend the money gained from the West Indies to fund a massive fleet of galleys and light transports, and he reorganized his soldiers into Legiones, who fought in the Swiss style, and with this massive new military, Manuel declared war on the Turk with the aim of the conquest of Tunis.

Manuel IV was an otherwise sensible and levelheaded man who was seduced by the glory that his wealth could give him. Paulo Machiavelli, who was Italy’s ambassador to France at the time, was known to call him “the slave of fortune”

The war went well at first. Portuguese galleys and galleons were growing to be more advanced than their Ottoman rivals, and several Italian states joined the war, worried at what capital they would lose should Manuel fail. Francisco Erno, grand admiral of the Venetian republic, became the commander in chief of the operation. This was for the best, as the Venetian navy was easily one of the most experienced navies in the world at the time, and Erno was an old hand, trained under fire in the use of mixed operations during his wars with Barbary pirates. But Erno was also, most importantly, not Portuguese, and he had no loyalty to the arrogant king of Portugal. So he used the Portuguese navy as bait, sending them to fight the Turks and then retreat to the Alboran Sea, where the Turkish fleet would then be pincered between the fleets of Portugal and a coalition of Italian states which included the Duchy of Modena and the Republic of Venice.

The naval plans for the War of the League of Sardinia. Dark green denotes Portugal and her holdings, light green the Ottoman holdings, light blue represents the members of the Italian coalition while dark blue represents members of the Italian League who also joined the coalition. Solid lines indicate the first stage of the plan, dotted lines represent the second stage.

The plan went perfectly, helped along by Erno’s knowledge of the commander of the Turkish fleet, the Greco Bey, who was overeager and undercautious. But being used as a rapidly moving anvil weakened the Portuguese fleet drastically—battles fought first on the coast of Algiers and then all along the Western Mediterranean led to hundreds of galleys and several capital ships being lost to attrition, storms, and the attacks of quick Turkish raiders. So though the Battle of Granada led to the sinking of much of the Ottoman naval presence west of Malta, it also annihilated the Portuguese treasury, which needed to be used to rebuild the fleet. It also crippled the transport fleet, which led to the war dragging out for 7 whole years. By the Treaty of Sardinia (in 1610), which gave Manuel IV the cities of Malta and Tunis, Portugal was deep in the pocket of Italian bankers.

Fall

We have every indication that this was done purposefully—Erno boasted many times that he had defeated two enemies with one battle at Granada—but it had ripple effects which hit the whole world. To pay off his debts, Manuel IV had to find revenue somewhere. This somewhere, argued his advisers, could be the West Indies. Manuel had never levied a tariff on the region’s trade, even though Portugal controlled every entrance to the Gulf of Mexico. With that tariff, argued his advisers, he could recoup his losses and look strong in the eyes of the world.

This tariff may have been possible in the 1580s or even the 1590s, but it was not possible in 1600. The late 16th century featured multiple battles between the French and the Spanish across Germany, with especially intense fighting occurring in Switzerland, with France supporting the Protestant cantons and Spain supporting the Catholic ones. The only reason these battles didn’t turn into a full fledged war was the constant toil of d’Estrees and the Spanish ambassador Montecello. But in 1608, the Treaty of Bearn occurred and signaled the exit of Spain from the wars of religion and renewed friendship between the French and Spanish kingdoms. Without a war to fight in Germany and without an enemy on the other side of the Pyrenees, king Charles III started looking back to his colonies to provide the gold required to pay off his debts and pay for public works projects. The Portuguese Tariff only reminded him that his weak neighbor threatened to cut him off from the entirety of his New World territories.

There were two other reason that the Portuguese tariff was highly unwise: firstly, Portugal simply did not control the whole of the Caribbean anymore. Bishop Biard had seen the colonies in the South, led by a Catholic King who chose not to convert his subjects to the true faith, as a center of blasphemy, and thus started sending missionaries to the Caribbean starting in the late 1590s. These missionaries eventually signed treaties that linked tribes in the northern Bahamas and in the Antilles to Canada, and French Jesuits and soldiers were well aware of Hispaniola and had had some contact with the tribes there.

Jean Claver, who was born in 1560 and assigned as the vicar general of the West Indies in 1606 (well before France or the Jesuits had any influence in the region) soon surpassed his capacity as a preacher to become an advocate for insurrection by the Taino Indians against their Portuguese masters

Lastly, the Portuguese West Indies was not a militarized colony, capable of sustaining a war. Its captains were untrained, its supply depots were empty, its links to the tribes easily broken. The Portuguese fleet had been traditionally seen as a home defense fleet, and as such only 4 squadrons of light transports were assigned to the area. The Viceroy of the West Indies, Rao Estobal, had never been tried in combat. But he was just as arrogant as his superior.

Estobal saw the Jesuit missions (which were primarily staffed with French and Canadian Jesuits) as an infringement on his territory, and made repeated attempts to push them out of the Viceroyality of the West Indies. But his attempts were failing--the Jesuits were increasingly entrenched in their bases in the northern Bahamas and used that base to send missions to Hispaniola and other islands in the Viceroyality. Estobal decided that he needed to eject the Jesuits somehow. So on the night of the 14th of February, 1610, Estobal sent a group of Portuguese soldiers, dressed as pirates, to burn the mission of Thaumond down. But the soldiers didn't expect the level of resistance they faced. A garrison of 15 Frenchmen guarded the mission, and the battle between the garrison and the Portuguese raiders went through the night. As dawn came, Thaumond was burned to the ground, but 3 men of the garrison survived and made the trip to Cuba. There, the Viceroy of New Spain was told of the actions of the Portuguese, and news quickly got to France. The declaration of war by the Spanish and French kings was the first unified act by the two kingdoms since 1575, and was soon met by a declaration of war by England against the new Franco-Spanish bloc.

A storm was coming to the West Indies. A storm which would destroy the old order.

Last edited:

well one message there is don't trust your fleet to a Venetian

and now everyone seeks to feast on the corpse of their empire

and now everyone seeks to feast on the corpse of their empire

well one message there is don't trust your fleet to a Venetian

and now everyone seeks to feast on the corpse of their empire

That's a really fantastic phrase--I imagine some really old sailor saying it at a tavern.

I think that I'm going to make it come up later just for that.

Last edited:

Please do, that was my reaction as well!That's a really fantastic phrase--I imagine some really old sailor saying it at a tavern.

I think that I'm going to make it come up later just for that.

Also, fantastically ominous update. Gameplay question - is there an in-game justification for the 'native allies' of the portuguese? It has been WAY too long since I've played MM - basically since I got HTTT and a mac. Always tempted to reinstall Complete tho, just to play MMP.

Please do, that was my reaction as well!

Also, fantastically ominous update. Gameplay question - is there an in-game justification for the 'native allies' of the portuguese? It has been WAY too long since I've played MM - basically since I got HTTT and a mac. Always tempted to reinstall Complete tho, just to play MMP.

The Portuguese either had small colonies or no actual presence in the Lesser Antilles. The only actual colonies they had were in Hispaniola and Puerto Rico. But they also spent most of their NIs on colonization or trade ideas, and they chose 'trade superiority' as their colonial policy, so I decided to go with that for the reason I invaded the area (also because I really wanted those islands--sugar starts to become insanely profitable around 1600 or 1650)