yourworstnightm: I was a bit surprised, but nevertheless pleased by what the Brits managed to assemble in Scotland.

Viden: They are... in Austria and Poland.

Kurt_Steiner

Kurt_Steiner: Indeed, and the front lines still aren't anywhere near them.

Enewald

Enewald: Land where?

Nathan Madien

Nathan Madien: Looks like you don't need my help now.

-----

The United States in the World War - Part VIII

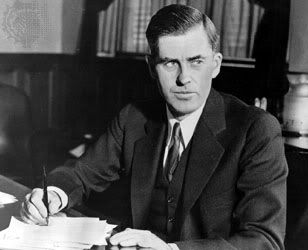

As the incumbent party in power, the Democrats assembled for their national convention a month after their Republican counterparts. Held in Chicago, the former heart of the Syndicalist rebellion, the nation's worse kept secret was Roosevelt's intention to run for a third term. Despite this precedent-setting move, breaking an unwritten tradition in American politics, the party was only too eager to grant Roosevelt his wish. No serious opposition stood in the President's way, and few could deny that he maintained an impressive electability; having weathered civil war, officiated over sweeping reforms and policies that returned economic prosperity, and command-in-chief through two successive wars, Roosevelt's experience was undeniable, his personal charisma undiminished, and his political intuition as sharp as ever. But the reality was not all good; stricken by polio and enduring the strain of governing the nation for eight years had taken an unmistakable toll on the President's health. Many, accustomed to a warm and energetic voice over the radio, were often shocked at the sight of Roosevelt's frailty. The difference between Roosevelt and Willkie was obvious.

Roosevelt aged significantly in the eyes of many Americans.

In spite of the Roosevelt's assurances that he was healthy and as fit as ever to serve as President, several delegates nevertheless began to see the choice of Vice President, the only issue still in question even as the convention began, in a far grimmer light: as the inevitable successor to the Presidency. Henry Wallace, serving faithfully as Vice President since his fateful decision in 1936 to throw his lot in with Roosevelt against Garner, naturally assumed his renomination would follow without any undue difficulties.

Left-leaning, Wallace served as a lightning rod for former-Syndicalist voters, and also for the criticisms of the more staunchly conservative elements of the Republican Party. As such, the Vice President ultimately found himself at odds with many of Roosevelt's advisors within the administration, his presence something to be tolerated or endured rather than welcomed. Roosevelt's own style of hands-on governance also meant Wallace's influence within the government remained at a dreary minimum. With more time and less responsibilities, Wallace was allowed to indulge in a peculiar private life for the time. A mystic in simple terms, Wallace was involved with the Russian intellectual Nicholas Roerich; though neither scandalous or illicit in nature, the relationship, if brought to public attention, would prove an embarrasment.

Such issues, however, were dwarfed by the growing rift between Wallace and Roosevelt regarding the conduct of the war. A Syndicalist sympathizer to a large extent, Wallace believed that cooperation, not conflict, with Syndicalist Europe was essential, and that the war should be brought to a speedy conclusion. American honor, he insisted, had been restored in full; the attack on the Atlantic Fleet hardly warranted an all-out war with the entire continent. For his part, Roosevelt had remained ambiguous on overall American objectives, not wishing to commit himself and therefore limit his freedom of action in the future. What considerations the President operated under eluded even his closest advisors, and this frustrated Wallace to no end.

Had Roosevelt insisted, Wallace would be renominated Vice President without a fight. But even the President had his misgivings; Willkie was unlike McNary or Curtis; with humble Midwestern origins, a dynamic appeal, and ties to big business, he could appeal to a wide spectrum of voters, wide enough to clinch the election if Roosevelt was not careful. The President, therefore, began looking for alternatives: support for Senator John Bankhead, an Alabama lawyer who, though an advocate of poor farmers, refused to fall prey to National rhetoric prior to the civil war. His background, it was hoped, could also draw off voters from the nascent Southern wing of the Republicans; his popularity had allowed him to survive the civil war and emerge to win a House seat twice. But it was a little-known Missouri Senator by the name of Harry Truman that emerged as a prominent dark horse candidate. Drawn from humble Midwestern origins just like Willkie, Truman gained local notoriety during the civil war organizing relief for his fellow farmers against the oppressive collectivist directives of the Syndicalist authorities. In 1940, they repaid the favor by sending Truman to the Senate, where he once again distinguished himself by investigating charges of corruption and waste in the wartime military, in particular an unnamed multi-billion dollar project, that served to greatly annoy Roosevelt.

The first ballot for Vice President indicated that many of the more liberal Democrats refused to abandon Wallace, with 397 cast in his favor, with the rest split almost evenly between Truman and Bankhead, with another 150 scattered amongst a bevy of lesser candidates. Bankhead's relative obscurity outside of the Deep South proved his undoing, as the remaining conservatives and moderates began to shift to Truman on the second ballot. Enraged, Wallace demanded that the party leadership renominate him; 'Americans won't stand this slaughter in England much longer!' he was said to yell, 'And they won't stand for you much longer either!' Undeterred by his threats, the third ballot decisively swung toward Truman. Approximately 250 delegates, the core of the liberal wing, stayed with Wallace, as the rest rallied to Truman, clinching him the nomination. Disgusted with what he saw as an abandonment of the socialist principles of the new Democratic Party and the 'New Deal' reforms, Wallace dramatically denounced the results and stormed out of the convention, taking his supporters with him.

Harry Truman at the convention, Democratic Vice Presidential nominee.

If America was surprised by Truman's nomination, Wallace's walk-out came as a complete shock. In an instant, the party seemed to be rupturing. Republicans breathed a sigh of relief; rather than facing the daunting left-center coalition held together by Roosevelt and Wallace in '36 and '40, it seemed their opposition was disintegrating right before their eyes. Roosevelt put up a calm front, but privately scolded Democratic leaders: 'I don't intend to lose this before I even begin.' Mustering his strength, Roosevelt took center stage on the final day of the convention and unfurled into a magnificent speech, rivaling that which inaugurated his New Deal in '36. Roosevelt began by vowing to maintain the prosperity brought about by his reforms and 'enact what measures may be necessary to ensure their greater benefit for the American people.' Continuing with denouncements of the threat Willkie represented to almost a decade of reform work, as well as the 'disorderly radicalism of certain factions of both conservative and liberal backgrounds' which 'threatens to disrupt the integrity of the political system so many thousands perished to persevere and protect.' However, all this paled in comparison to his pronouncement on the war:

And it must be admitted, my friends, that we live in perilous times. The grim specters of war, depression, and revolution appear in every foreign capital, on every horizon that we cast our eyes. Since the last great cataclysm that swept across Europe and the whole world, the old order of things has been overturned by a force no less threatening to the integrity of our great republic. One great radicalism has been replaced by another. At this very moment, this nation is engaged in a great struggle with that grave threat. Though we may be separated from the turmoil of the Old World by great oceans, time has shown that this is no defense against that which plagues the world.

It is by the good fortune of Providence and our own illustrious history that we stand at this moment in history as defenders of the great democratic principles, assured by our bountiful lands, booming factories of industry, and the stalwart character of the American people. My friends, it is time that we as a people take up the mantle fate has bestowed on us; should we ignore this grave undertaking and turn inwards as we did in the face of the last Great War, we will only invite disaster upon ourselves. Instead, let us all here assembled constitute ourselves prophets of a new order. The world must be made safe for America; the world must be made safe for democracy.'

Such an abrupt announcement, made in the chaotic and highly-charged atmosphere of the convention hall, begged elaboration, but the President was hardly forthcoming and short on details. Roosevelt's speech posed as much a direct challenge to Wallace and his dissenting Syndicalist cohorts as it did to Willkie, like-minded as he was on the issue of the war. In accentuating their similarities on foreign policy, Roosevelt seemed to be gambling that voters would choose the incumbent, who had proven himself capable in handling more wars than any other president in American history, in in the meantime preempting Wallace. The risk was very real indeed. Wallace threatened to tap into the sympathies of a very large pool of voters, voters who were growing increasing distressed at the stalemate in Scotland and the steadily-rising casualty lists; despite the years of social calamity and civil war, Americans remained as reluctant to send young American men to die on foreign battlefields.

Nevertheless, a new party had emerged on the American political theater following the Democratic convention. Showing no second thoughts and wasting no time, Wallace gathered his allies and disparate left-leaning elements, many of them the remnants of Reed's Syndicalist party, in New York City for the formation of the Social Progressive Party on August 3rd. Wallace, the hero of the hour, was nominated by acclamation. Choosing the Vice Presidential candidate proved far easier than it was for the Democrats: Earl Browder, a former-popular front communist from Kansas, was chosen for both his inclusivist stances and his relative lack of involvement with the rebellion. The Social Progressive platform called for reaffirmation of the New Deal, renewed reforms along socialist lines, and a negotiated peace with the Syndicalist alliance 'that satisfies the necessities of American national honor.'

Henry Wallace, Presidential candidate for the new Social Progressive Party.

Thus, Roosevelt had what he had wanted least: a referendum on the current war and, worse still, the defection of the leftist branch of the Democratic Party. The political landscape of the election had abruptly shifted over the course of just a few days, and the outcome of the November elections was suddenly cast into confusion.