Ah, finally figured out who the Wing Commander is. None other than Air Chief Marshal Sir Ronald Ivelaw-Chapman

Weltkriegschaft

- Thread starter TheHyphenated1

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Chapter III: Part XXXI

Chapter III: The Lion’s Den

Part XXXI

November 12, 1936

Fackel. Joseph Auspitz had been resting at the home of Moss Twomey, the Irish Republican Army’s Chief of Staff, when the daily signal from occupied France came over his radio. Fackel. Torch. The codeword signaled the Abwehr’s decision that a general uprising should begin in Ireland within a fortnight. That had been October twenty-eighth, and the intervening two weeks had seen final plans set in motion to rekindle the Old Resistance. Now, in just hours, the Second World War would at last break over the Irish Free State.

Auspitz huddled over his wireless set in a barn in County Donegal. He heard the new codeword a second time. Lauffeuer. Wildfire. The codeword for the general uprising to begin. Auspitz took down the rest of his instructions, then concealed his radio set. He walked out to the barn door where Seamus O’Donovan was having a smoke in the midnight air.

“It’s on.”

The IRA chieftain said nothing, but the end of his cigarette glowed bright red in the dark.

“Word from Germany is that they should have men ashore very soon.”

O’Donovan let the cigarette fall from his lips and stamped it out with the sole of his boot. “By sea or by air?”

“I -- I believe the plan is still by sea, and just the Treaty Ports. Even larger than we thought. I asked about Galway, but did not get an answer.” Auspitz was referring to the three ports in the southern twenty-six counties of Ireland that remained under British control. IRA men had spoken to members of de Valera’s government, and indications were good that he would not interfere with German operations against these ports insofar as they were of military value in the ongoing war. He might even be disposed to look the other way if the IRA participated directly. And so, Auspitz had been under intense pressure to obtain assurances that Germany would not take any action against the port of Galway, which belonged to the Free State. The Abwehr had not proven willing to make any such assurances, and Auspitz was highly skeptical of their motives in not doing so once Fackel had gone out.

“I just hope t’God they don’t. Would really sour Dev’s people on this.” When O’Donovan saw that the German was just as concerned as he was he nodded. “I’ll telephone someone who knows where MacBride is.”

Auspitz gave his assent. Seán MacBride, the center of their prearranged communications network, reportedly feared that Auspitz and his erstwhile colleagues in the George cell would betray members of the old Anti-Treaty IRA to de Valera in return for his government’s cooperation. He had refused to interact with the Germans other than through intermediaries, and Auspitz had consented to this treatment on O’Donovan’s advice. MacBride’s men, with their knowledge of the telephone and telegraphy networks, would were now poised to send the first nerve impulses of the Lauffeuer signal out through the country -- like wildfire.

Following sustained unrest in and around Belfast, including widespread and relatively successful IRA sabotage, the Abwehr had decided that the iron was hot. Better, they reasoned, to start the uprising in the south now, before the one in the north could be put down, and before any more of the British Army could be ferried from England. With luck, de Valera would see the situation similarly, and accept German assistance in driving British loyalists from the island like so many snakes. If anything was done to alienate him, the forces of the Free State would inevitably try to crush the IRA insurrection -- setting up a Second Civil War at odds that did not favor the guerrillas.

On the sixth of November, they had practiced the muster signal in anticipation of the real thing. From O’Donovan relaying the codeword to four thousand men gathering at their secret assembly points around the country was little more than two hours. If that speed was achieved tonight, the IRA brigades would be ready to assault the Treaty Ports two hours before dawn.

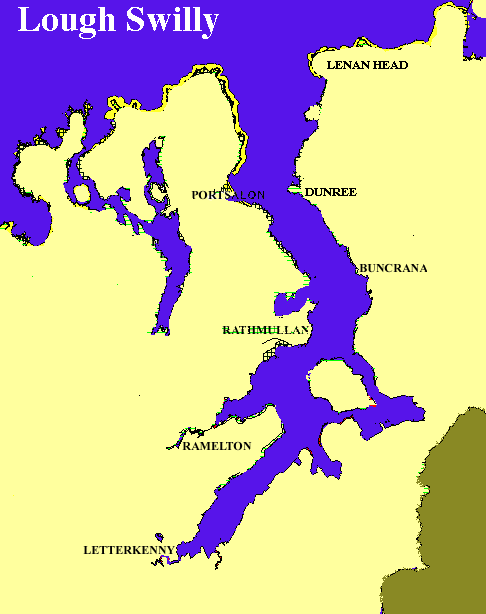

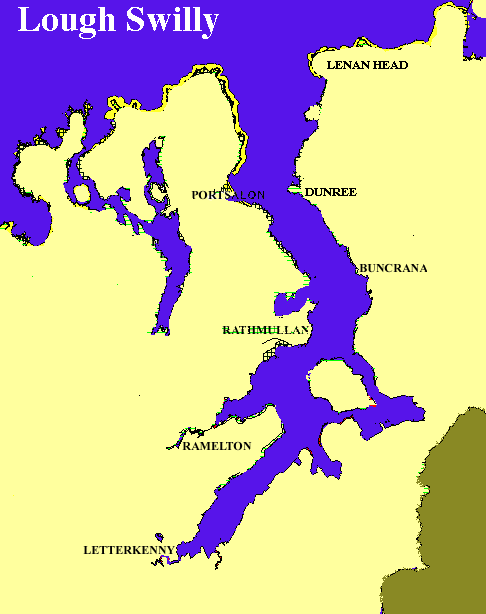

At Cobh, Tom Barry would lead a large number of men, many from County Cork, in an attempt to seize the most vital port on Ireland’s south coast. At Castletownbere, Jimmy Steele would lead a smaller raid to secure the town’s docks and neutralize its coastal defenses. The largest assault would come at Lough Swilly, just 10 kilometers to the north of the barn where Auspitz now stood.

According to reconnaissance, three Royal Navy vessels presently were sheltering in the lough. HMS Codrington, a modern destroyer armed with five 4.7 inch guns and eight torpedo tubes, would pose the greatest threat. HMS Halcyon, a minesweeper coming off repairs at Belfast, was docked nearby. Finally, a supply ship of unknown name sat at anchor near the town of Buncrana half way up the lough.

The plan called for O’Donovan and perhaps as many as 1,700 armed men to march into Letterkenny at the southern end of the lough, raising the alarm and trying to bring the police into the uprising. From there, they would race north and storm the Royal Navy’ shore installation and armory. Meanwhile, men would be trying to sink the ships in the lough with explosives. By now, with the hue and cry being raised throughout the county, more men would gather in Letterkenny to the sound of ringing church bells. O’Donovan would see to arming them with captured and spare weapons, then reinforce the eastern roadblocks set up by his cousin Ernan’s men to prevent British troops out of Derry from interfering. Meanwhile, Auspitz was told, fighters further up the lough would join small teams of German soldiers in disabling the defensive shore batteries, allowing the approach of the German ships that would firmly secure the port.

“The word’s going out, Captain.” O’Donovan was back. “A car’ll be here for us soon.” Auspitz noticed that the Irishman had a Soviet-made submachine gun slung over his shoulder and two bandoliers of improvised explosives across his chest.

“I hope,” Auspitz said sincerely, “that the police do not shoot you.”

“For their own sake,” O’Donovan grinned.

The Abwehr had been adamant that the uprising be carried off in such a way that the IRA not be brought into conflict with official Free State forces unless it was certain that they were offering resistance. In the critical first hours, the uprising was to present itself as a strictly anti-British popular movement. This presented a serious strategic difficulty -- planning Wildfire for both contingencies. That is, the insurrectionists had to be equally prepared to work with Éamon de Valera’s government if it chose to side with Germany against the British military, and to depose the very same government if it attempted to hinder the uprising. Experience told Auspitz that the result would likely be a patchwork of both eventualities.

A blacked-out automobile arrived with a driver and bodyguard and took O’Donovan and Auspitz overland to the tiny church near Cairn High on the west bank of the lough. A light was on in the belfry, and as the driver cut the engine and entered with O’Donovan, it was extinguished. Out came about a dozen fighters, heavily armed and with Ernan O’Donovan at their head.

“Y’remember Captain Auspitz, Ernan.” Seamus said as Auspitz stepped out of the car to meet them.

“Of course I do,” he said, lowering his Thompson submachine gun to shake the German’s hand. “Pleasure.”

Auspitz and the two O’Donovans agreed on a plan of action. Hauptmann Auspitz was to follow Ernan and his men to the cache of guns just a few kilometers to the north at Garrygort. Shortly after they got there, about 250 men were expected to converge on the area. They were to oversee the orderly distribution of arms and then march southward with all haste to Letterkenny, where they would meet Seamus’ larger force as it came up from the southwest.

Lough Swilly, County Donegal.

Up the narrow road they marched, kilometer by slow kilometer, keeping watchful eyes on the dark hills piled around them. Auspitz had the most formal training of any of them, but was in awe of the way they knew the country. With each step, Ernan checked the sounds of the night. These men could sense danger in these hills better than anyone -- Auspitz trusted their instincts far above his own.

They were nearing an intersection with a wider lane that had a ditch on the far side. All of a sudden, the men at the front drew to a stop at the same time. No one spoke. Auspitz listened, but the dead hours were still and silent. His mouth was dry -- it was dark ahead, he strained to see.

Something wasn’t right. Auspitz sensed a presence in the deep shadows of the roadside ditch ahead. He could sense that the other men were thinking exactly the same thing. The hairs on the back of his neck were standing up. Something wasn’t right at all.

“Ho!” Ernan raised the Thompson in the dark. All around, Auspitz heard the other fighters aiming their weapons into the gloom. “Ho!”

There was a moment of silence -- Auspitz couldn’t in his state of thunderous alertness tell whether it was ten seconds or less than one -- and then the sound of undergrowth crashing just meters in front of them. At the same instant, dark faces emerged from within the ditch and Ernan’s fighters bellowed calls to surrender. Somewhere to Auspitz’ right, a hunting rifle discharged, its muzzle flash illuminating a multitude of shining eyes in the ditch.

The next thing he was aware, Auspitz was leaning over Billy McCaughey’s bloody abdomen, trying to calm him as he applied pressure. The terrified boy couldn’t have been more than sixteen.

“Captain, captain!” Shouting as though from a great distance. An arm was tugging at Auspitz’ sleeve.

He looked up to find a knot of Ernan’s fighters nose-to-nose with men in German uniforms, on the verge of blows. Both sides had guns pointed at each other and were shouting in mutually unintelligible languages. One of the Irishmen was jabbing a thin-faced German with his sawed-off shotgun. Leaving Billy McCaughey to the care of one of his brothers, Auspitz physically placed himself between the two sides, begging for calm in both languages.

The strangers wore Heer uniforms but had faces painted black like minstrels, and wool caps instead of helmets. In German: “I am Luftwaffe Hauptmann Joseph Auspitz, here in Ireland as commandant of the Abwehr’s mission in the Free State. I want to know who you are and why you shot someone. These Irish are friendly.”

The man who had been jabbed with the shotgun turned to face Auspitz. “Oberleutnant Poch. Good. You take orders from the Army now. The invasion has begun.”

“You must at least give this man medical attention --”

“Not in the road.” Poch ordered two of his men to carry McCaughey into the field beyond the ditch where his men had been lurking.

Once they were out of the road, the Germans seemed to warm up, and two of them treated McCaughey while his worried comrades stood around him. Poch discussed the incident apologetically with Auspitz. It seemed that it had been McCaughey who had fired first into the ditch. One or two of the Germans, equally startled, and not fully certain as to the allegiance of these armed irregulars, had fired back in the direction of the shot. Poch’s goal was to stabilize the wounded man an get him to a friendly farmhouse, which could call for a doctor when they had departed. Did Auspitz know of one? He answered Poch that some of the Donegal men would surely know the land better.

The two conferred about the start of the operation. Poch said that he and his six men had been inserted by submarine, along with a raft full of explosives that he needed help getting safely off the beach. They would have to get up the mouth of Lough Swilly to disable the defensive artillery there. He fired off a battery of reconnaissance questions, most of which were different from the ones the Abwehr had told Auspitz to anticipate. When were the watch shifts at the base of the lighthouse? How far could the heavy coastal guns be traversed? Was there a ’round-the-clock guard on the Inch Island causeway? Where did the chief of police in Letterkenny live? Was the Oldtown Bridge stone or concrete? How deep was the water off Lenan Head?

Auspitz somehow managed to halt him. “Write down your questions, Oberleutnant, and I’m sure I can have someone get you the answers you need. For now, I just need some more information myself. Are your men alone?”

“No. Two other teams should have been put ashore somewhere in the lee of something called, I think -- no, it can’t, or -- something like ‘something-Head’.”

“Malin Head? That’s just north of the mouth of Lough Swilly. Is that it?”

“I think so. Two teams should have gone in on that side, but we haven’t heard from them since our submarines parted company at fiftieth parallel north. They could be delayed or lost, and we’ll have no way of knowing.”

Almost forty minutes had elapsed before they managed to get Billy McCaughey to a friendly farm and start out on their way north -- and for the narrow inlet where the Germans’ raft had been beached. Auspitz and Ernan agreed to send one of his men ahead to the cache at Garrygort while the rest helped offload the explosives, which, Oberleutnant Poch complained hotly, had been loaded far in excess of the realistic carrying capacity of his men. Ernan had been loath to risk the delay entailed in hours’ extra marching in the dark, but without taking out the guns that guarded the lough, the rest of the uprising in Donegal was doomed to failure.

They reached the raft without meeting anyone on the way, and trekked the explosives up near the mouth of the lough, where medium artillery had been emplaced at Knockalla. The guns here were not continuously manned, and so Poch’s men would simply rig their charges for detonation at 0500 and then proceed down the lough’s western shore to Macamish Point, where three smaller guns could be disabled with leftover explosives. Last would come the guns of Rathmullan, which would be destroyed just as the IRA fighters were beginning their assault. Carefully repeating the timetable to Poch, Auspitz wished him luck and led his men back south to Garrygort.

They arrived at the site to find no more than a hundred men, all of them milling about aimlessly and almost none of them armed. None of them seemed to have seen the runner they had sent ahead to open the cache.

“Where is he, Ernan?”

“I don’t know, Captain.”

Auspitz swore. “Then -- he -- he could have just gone off and betrayed us?”

“I know Bobby as well as anyone and he’s firmly with us.”

“But there is no other explanation. It’s been enough hours for --”

“Listen, Captain. Even if he has betrayed us, that doesn’t make any difference now. What’s on is on. Start handing out rifles.”

This undersized company was on the march southward by 0415 -- almost two hours behind schedule. They had not long passed the Cairn High church when the throaty rumble of demolition charges rolled over the still waters of Lough Swilly. Again and again the explosions sounded in the distance -- but rushing to a bluff, Auspitz saw nothing.

The rolling hills along the western shore of Lough Swilly.

About a quarter of an hour later, another set of charges went off, closer this time, and then silence. The sky was getting light by the time they came, after half a night of frantic marching in the dark, upon the fading lights of Letterkenny. Auspitz had half expected to see the town ablaze, or hear the sounds of gunfire, but he did not. The town looked almost peaceful as Ernan O’Donovan’s company descended from the hills.

They arrived unmolested at St. Eunan’s Cathedral, where Auspitz found Seamus and his lieutenants gathered, surveying the commanding view from the cathedral’s tall tower. The twelve great bells were pealing urgently, calling the muster.

“Only nine hundred, Captain,” O’Donovan said grimly as he gazed out over the lightening scene. In the blue-gray mist to the north, the minesweeper Halcyon sat inexplicably at anchor. “But more are coming. More may yet come to the sound of the bells.”

“We came into the town without being challenged, Seamus,” Auspitz hissed. “You must send men down to man the western and southern roads!”

The IRA chief didn’t lower his eyes from his binoculars. “With respects, Captain Auspitz, I d’n think you heard me. We’ve only got nine hundred men. Half of what we should. There aren’t men to block anything right now.”

“What about the police?”

“That’s the good news. The city is ours and except for a few fools, they’re staying out of the way. We’re mustering our next battalion all along Upper Main Street, down there --” he pointed a finger into the town center below, “while the nine hundred are marching up the eastern shore of the lough.”

“And the British?”

“That’s the bad news, but it could be worse. They’ve pulled back to Buncrana, including the destroyer. By how quick they did it, they probably had warning.”

“Now they can only be waiting for reinforcements from Derry,” one of Seamus’ men added, “and those can’t be long.”

“How many are there?”

O’Donovan sighed. “Several hundred men from the port, and a few hundred more regulars. They have us almost matched in numbers, and the advantage of the guns.”

“The guns? We heard the charges going off hours ago.”

“The destroyer’s guns, I mean. Out of the six main shore batteries, we’re mostly sure that four are down.” He pointed into the distance, sweeping his arm across the western shore of the lough. “Knockalla, Rathmullan and Macamish are blown, ninety percent certain, and we haven’t heard a pip from them. Unlikely that crews ever got to man them. The small guns on Inch Island -- that green mound that looks like a foreland of the eastern shore -- were destroyed, and we met the German saboteurs that did it. So we’re left with three hard places: the heavy nine-inchers at Lenan Head, the fort at Dunree and the medium guns all around Buncrana.”

“You never heard explosions from those positions?”

“Oh no, we did. But we’ve also heard the fire of heavy guns from that direction. We don’t have anything that heavy.”

It was after seven, and the sun was just shearing through the dawn mists to the east of Letterkenny. “How many men does Ernan need to hold the road from Derry?”

“Two hundred, at least. That’s enough for a delay, at least.”

Auspitz sized up the eastern ground. “Then give him a hundred, and two of the heavier machine guns. Everyone else is to form up with me at the Courthouse and then march up north. The battle will be at Buncrana.”

“Jack, Tom, Johnny,” O’Donovan said to the lieutenants around him, “do as Captain Auspitz says.”

It was not long before Ernan was sent east with a hundred men to block the way of any force force from over the border in Derry, while Auspitz scraped together as many men as he could to reinforce the nine hundred already headed for Buncrana.

Precious minutes of initiative passed as IRA fighters trickled onto Upper Main Street in nothing near the sense of hurry Auspitz thought warranted. He exhorted the officers to get them going. If the guns of Buncrana weren’t silenced -- to say nothing of the long guns at Lenan Head -- the German ships coming into the lough wouldn’t stand a chance.

“Message for Cap’n Spitz from Mister O’Donovan, sir!”

Auspitz whirled. A blue-eyed boy of twelve had sidled up behind him. “Yes?”

The boy handed him a scrap of paper.

Castletownbere report poor. Steele dead. RN cruiser holds port. --O’Donovan

Biting his lip, Auspitz scrawled off a reply.

Any word on Cobh? Am going to Buncrana. Telephone Twomey for reinforcements. --Auspitz

The boy darted back toward the cathedral with the message, and Auspitz turned to the IRA officers around him.

“Head-count?”

“We can probably get four hundred if we --”

“Not probably! How many men are on the street right now?”

Counting took several minutes. “Two hundred and fifty or so.”

These were the most dangerous few hours of the entire uprising. Further delay, Auspitz knew, could prove fatal. “Form them up!”

With Auspitz at the head, 213 men set off double-quick on the three hour march up the shore of the lough to Buncrana. They proved to have excellent stamina, and the German found himself taxed trying to keep up. He slipped up and down the column, inspecting the arms of the fighters -- at least half had automatic weapons, he was immensely pleased to see, but ammunition was short. The fastest men he posted as screens ahead of the column to deter ambush, but none materialized on the open road winding through the hills east of Lough Swilly.

Lough Swilly, seen from the south, looking out over Inch Island.

Just after ten, the sound of gunfire became audible ahead, and Auspitz ordered his ad hoc company into a skirmish line. Cresting a wooded bluff, they saw the battle a few hundred meters below.

About a hundred British regulars were dug in around an apple orchard outside the town of Buncrana, trading fire with a large mass of IRA fighters spread across a gentle stony slope.

Auspitz turned to his men. “Hold here.”

He sprinted down the slope, weaving between Irishmen as the enemy raked ground around him. He picked out O’Cannon, the leader of the force, and ducked behind a boulder not far from where he was standing. The air was full of sharp rifle cracks and grumbling bursts from the Irish submachine guns. From his position he could see two Irishmen fallen in the road, and another slumped against a tree. White smoke hung over the Irish lines.

“O’Cannon!” Auspitz cupped his hands to his mouth. “O’Cannon!” Louder: “O’Cannon! Come here!”

The forty-eight year old son of ancient nobility broke from his cover behind a tree and ran to the German’s side. “Captain?”

“Yes. Listen -- the way those marines are shooting, you’re never going to win like this. They’ll just wear you down. Do you understand me?”

“Yes.” His proud blue eyes belied serious leadership deficiencies. Unused to pitched battle, he had done perhaps the worst possible thing, and gotten his men checked by a force they outnumbered almost ten to one.

Auspitz pointed up the slope. “I have two hundred good men with me. Listen -- you are pinned down right now -- you cannot advance without getting shot up. I do not want you to advance. I want you to get your men ready to all fire at once. I will take my men into that sunken lane over there. We will get around the side of the orchard, where the road curves by that yellow farmhouse. Do you see that?”

“Aye.”

A fighter standing next to the boulder screamed in pain and crumpled. “Look at me, O’Cannon! I want each one of these men to start shooting as soon as you see us reach the yellow farmhouse. You’ll be able to see us as we move toward it. Once we’re there, shoot like a devil into the orchard to keep their heads down. This will allow us to come around and get them.”

“Aye. I’ll tell the men.”

Auspitz scrambled back to the crest of the slope and relayed the plan to his company. They jogged into the sunken lane, keeping their eyes on the yellow farmhouse half a kilometer ahead.

“Go! Go!” The company broke into a run, following the curve of the road around the farmhouse and emerging into an empty field next to the orchard. The men on the slope slope came alive with supporting fire. Auspitz unslung his MP34 and pointed at the crouching figures ahead. “At them! At them!”

The men rushed forward, firing hotly at the already-engaged British. Some tried to break into the road and and flee to the west, but most of these were cut down in the crossfire. The blistering firefight lasted less than a minute, and when it was ended, Auspitz counted just four dozen British soldiers still standing. Directing the dazed surrenders under guard to the rear, he ran to rejoin O’Cannon as he brought his men down the slope.

Congratulations were brief. “What we must do now,” Auspitz told him, “is to storm the town of Buncrana itself.”

Although the men were already exhausted from a speed march from Letterkenny, they would have to assault Buncrana and its coastal artillery quickly. The HMS Codrington was loitering just off the docks, and with its large guns could decimate the Irish as they crossed a 900 meter wide exposed greenbelt outside the town. Once they were in the town, they would be protected from the destroyer’s guns and too close to the defenders for the Codrington to be able to fire on them safely.

An automobile horn oogahed as its driver nudged through the dazed fighters toward the two conferring leaders.

Seamus O’Donovan stepped out. He congratulated O’Cannon warmly for the daring assault before turning to Auspitz. “No word on how the battle for Cobh is running. But two pieces of good news. First is the Lenan Head and Dunree guns were blown up. Eight lorries of our boys and the Carndonagh lot took ‘em down along with some Germans. Just like we thought, most of the gunners are quartered farther to the south, and ‘cept for a few hot exchanges, the boys almost walked right in. ‘Parently the gunners who were there got nervous, though, and shot up a neutral ship in the mouth of the lough before it was all over -- we’ll see to that later. The second bit is that I’ve got near two thousand more boys coming up the road now under Seán Russell.”

The German raised an eyebrow.

“Five hundred are veterans, he says, and the rest are just eager. Most of them aren’t armed, anyhow. The first of them will be here in an hour.”

Auspitz checked his watch. That means a little before noon. “Fine. But I want you to make sure Russell follows our plan of attack.”

Russell’s motivated column arrived a quarter of an hour ahead of schedule and he immediately joined Auspitz, O’Cannon and O’Donovan on the slope overlooking Buncrana.

Auspitz drew up the attackers into three formations. O’Cannon would lead the inexperienced men -- almost two thousand in all -- and lead them around to the northern side of Buncrana. O’Donovan and Russell would each lead several hundred of the hardened fighters -- the former from the south and the latter from the southwest -- and cross the greenbelt under fire. They would take casualties, Auspitz said, but both commanders knew that their men could take them and keep going. O’Cannon, of course, insisted that his own brigade could fight to the last.

“Yer problem is that you’d give them a chance to do it, Tom,” Russell scowled.

“Gentlemen.” Auspitz turned back to the map he was drawing in the soil with a small branch. “Seamus from the south and Russell from the southwest. You must get across the open ground fast, and fight those marines where the destroyer can’t support them. Once you are pressing them strongly, O’Cannon’s larger force sweeps in from the north --” Auspitz drew a large X over the British defenses, “-- and overruns them. Meanwhile, I want to get every heavy machine gun from your men. They’ll have to move too fast to set them up anyway. I want you to set up a base of support fire in that long stand of trees over there. It’s out of the destroyer’s line of fire but is in a good position to lay fire on the town. Is that agreed?”

It was. At 1307, O’Cannon’s force signaled readiness from its position just north of Buncrana. Auspitz ordered the machine guns to lay fire into the town, and with a great shout, more than seven hundred of the IRA’s best fighters charged out onto the greenbelt and under the guns of the HMS Codrington.

At once, the destroyer started firing, its powerful shells tearing great clouds of Donegal’s black soil into the air. The Irish were lifelong skirmishers -- they spread out naturally and moved across the killing zone quickly, but the Royal Navy guns would not be denied. Dozens fell, never to rise, as the Codrington gouged terrible holes in the IRA lines.

After four long minutes, they surged among the neat, whitewashed houses of Buncrana, and the town came alive with a stunning volume of gunfire. At once, the Codrington’s battery fell silent, its sailors watching the battle with the same interest as Auspitz himself.

White smoke hung over parts of the town, marking roughly where the fighting was thickest. Fifteen minutes passed with no headway made. “Signal O’Cannon to attack,” Auspitz instructed, sending a man further up the slope with semaphore flags.

As Tom O’Cannon’s men swept in from the north, they too were checked by the British defenders.

With nothing else to be done from his position above the town, Auspitz and the IRA officers with him crossed the greenbelt on foot to join their men and perhaps influence the decision in person. When the German reached the fighting, several dozen of Seamus’ men were in a brisk firefight with the British defenders of a merrily burning grocery.

The Irish would duck out from cover to fire shotguns, pistols or Thompsons into the ruined store, and every few seconds a yellow flash strobed deep within as a machine gun spat a reply to keep the attackers at bay.

As Auspitz watched from behind a corner, one of the fighters ran forward with an improvised fuel bomb. Bullets kicked up the dirt around him, but he managed to reach the grocery’s outer wall and press himself against it. Without looking, he hurled his gasoline-filled bottle deep into the store and sprinted back towards his comrades. The glass bottle shattered, and the burning rags stuffed into its neck set the gasoline alight in a splash of orange flame.

Instinctively, Auspitz ducked around the corner and began firing his MP34 into the blazing maw of the store. “Go in! Go in!”

As he covered them, six fighters stormed in and returned signaling what they had seen inside. The defenders were dead.

They inched further up the street, watchful of every door and window, following the crackle of enemy gunfire. Men lay dead in the road, most of them Irish, surrounded by the white-gray powder that had been shot from the pockmarked buildings.

They climbed over a broken fence and emerged into an open yard between the cemetery and the side of the protestant church. Both sides were trading fire in the street, as two machine guns in the vestibule kept anyone away from the entrance. Firebombs had hit the stone walls in several places to little effect, leaving only great black scorch marks and smoldering clumps of grass below.

Christ Church, Buncrana, County Donegal.

Auspitz caught a flash of movement in one of the darkened windows and threw himself to the ground just as a stubby barrel poked out and began spraying the field with automatic fire. One of his men screamed that he had been hit. Rolling onto his side, Auspitz fired an entire clip at the window and scrambled behind a parked automobile a few meters away to reload. Two fighters were already there, also reloading.

“I think I might have knocked out the machine gun. When I say, I want you to start come out from --”

The windows behind him exploded in a renewed staccato of gunfire. All three men sheltering behind the car crouched as low as they could, pressed against its black body, just as the dull think of bullets pounded against the doors on the other side. One of the tires blew, and the next moment the gun fell silent.

“When I say --” Auspitz paused, expecting the the shooting to start again, “when I say, I --”

A sharp burst of gunfire slammed into the car again, rocking its entire body and showering Auspitz with broken glass. More fighters out of his line of sight screamed, hit. The Irishmen were firing back, but probably blindly and from cover.

Auspitz dropped to his stomach to look out from under the car. A water-cooled machine gun was raking the field in wide arcs. A man with a shotgun appeared from behind a large headstone in the cemetery and fired straight at the window. A shower of wood and brick erupted around the window-frame -- but the machine gun reopened fire before Auspitz even had time to hope that it had been silenced, battering the words from the headstone’s face as the shooter sheltered pitifully behind it.

He turned to the men next to him. “When I say, I want you to shoot right into that window for as long as you can.”

Misunderstanding, the nearer of the two leapt up at once and started squeezing off rounds from his old revolver. Auspitz pulled him down by the legs just as the man attracted the attention of the machine gun. It must have fired fifty more rounds into the stricken car, as Auspitz pressed his face into the earth for protection.

A tinkle and the loud whump of deflagration told him that one of the Irishmen had at last gotten close enough to lob a firebomb. Overwhelmed by the smell of burning gasoline, he held his breath and jumped up from cover to see flames pouring from the church window.

He shouted for the others to follow him, but they needed no encouragement. Several men charged forward and forced open the side door. Auspitz ran after them, his submachine gun up, through the doorway and into the church -- stepping over a wounded man and spraying the packed sanctuary with bullets.

He heard another tinkle and felt the roar and heat of a fireball slam into his back and throw him to the floor. As the smoke cleared, Auspitz pulled himself to his knees. He found at least twenty Irishmen inside the church, pointing their guns at a much larger number of British, many of whom didn’t seem to be soldiers. Their hands were up in surrender.

Auspitz joined O’Donovan, O’Cannon and Russell on the dazed street in front of Christ Church. The German’s ears rang, but he was almost certain that the gunfire was over.

“The destroyer’s pulled off and gone up a quare way toward Lenan Head along with the minesweeper,” O’Donovan said, dabbing a bleeding cheek with his sleeve. “Some of our boys got to the guns near here and managed to fire a few times. Made them nervous. Do you think the guns should be blown up now?”

“If you’ve got men who served on them in the last war, and can work them, no. But if you cannot put them to use, we ought to blow them.”

Aside from two of the guns, which had ready ammunition, the rest had none to hand, and so were ruined with explosives. As soon as the town was confirmed to be secure, Russell and O’Donovan agreed to detach O’Cannon and most of the non-fighters who had marched up with Russell southward -- there to keep order in Letterkenny and reinforce Ernan’s tiny contingent on the Derry road.

The aftermath of the Battle of Buncrana held a great surprise. Although the IRA men had at first appraised the enemy as nearly a thousand strong -- and had sent out a proclamation of defeating such a number -- it was not nearly so. Between the Battle of the Apple Orchard and that for Buncrana itself, they had faced no more than three hundred armed British. Although gravely outnumbered, their training had come to tell. Not thirty of them had been killed, in exchange for nearly a hundred IRA dead or about to die.

As the women of Buncrana came out to tend to the injured, a car trundled in from the north, with an urgent request for Auspitz to go north to Dunree. Legs numb from hours of marching down one side of the great lough and up the other, he slumped agreeably into the back seat. They drove north along the shore of the lough, two fighters hanging onto the runners for protection. The point at Dunree Head jutted up like a ship’s prow in the waters of Lough Swilly, crowned by a small fort first built to keep a different Continental enemy out of Ireland -- Napoleon. The car came to the top of the hill, and Auspitz shook his head at the strange sight.

A great British passenger liner lay off the adjacent Crummies Head, discharging dozens of boats into the shallow water. Some of the boats had already come ashore on the wide beach, and -- German soldiers were disembarking. Hundreds of them were already on the slopes, erecting winches or pulleys of some kind.

Farther out in the lough, Auspitz saw with surprise, a small flotilla of strange ships was steaming southward, in the direction of Letterkenny. He reached for his binoculars. There were two Norwegian-flagged cargo vessels, a long tanker flying the Stars and Stripes, and two staggeringly large French-flagged liners that dwarfed the one now sitting off Crummies Head. Some way behind these, two German destroyers loitered near a pair of masts sticking out of the water.

“Sunk by a U-Boat, Herr Hauptmann.”

Auspitz turned.

Oberleutnant Poch, sporting a broken nose, was standing behind him, his arm raised in salute. “And the minesweeper also. A lucky thing -- both of our destroyers have had problems with their gun turrets.”

Auspitz returned it. “What’s going on? I have received no word...”

Poch pointing to the men hauling tackle gear up from the beach. “We are preparing to make the fort here defensible again.”

Auspitz felt he was beginning to understand what was happening. “I was told that the British gunners here accidentally fired on a neutral ship. It was really one of our own under a false flag, yes?”

“Yes. If you walk with me not fifty meters along this hilltop, Herr Hauptmann,” Poch said, “you shall be able to see the situation.”

About 10 kilometers to the north, Auspitz saw, a ship was sitting dead in the water at the mouth of the lough, sending up a winding column of brown smoke.

“I have been told that that is one of the ships carrying ammunition. Once it was on fire, there was no hope of towing it to safety. It could explode at any time.”

Auspitz cursed under his breath. “Is that the only ship, then, that was lost?”

“I fear that it is not the only one, Herr Hauptmann. But you must speak to Major Kohler for the specifics, for I have heard very little.” Poch cast about for a few moments before leading Auspitz up the prow of Dunree -- to the overlook that commanded the lough where it was at its narrowest.

There they found the staff officer in conversation with a recently-arrived Seamus O’Donovan. Kohler introduced himself and brought Auspitz up to speed.

The invasion force had sailed several days earlier with the intent of steaming unnoticed through a powerful storm sweeping down into the North Sea from Iceland. Sailing separately and under false colors, nearly all of the ships attempting this route -- between the Shetlands and Faroes and then threading the shipping lanes north of Ireland -- reached Lough Swilly. One of the slower ships did not, he said. The converted liner Stuttgart had been stopped and sunk by a British light cruiser as it passed through the dangerous gap between the Stacs and North Uist in the Outer Hebrides, taking its precious cargo of more than sixty Panzer Is to the bottom.

Ships taking the southern route -- from Brest to Ireland’s south coast -- departed later, hoping to arrive off Ireland at the same time as the ships rounding the Shetlands. And here came the bad news, Kohler said. When the German ships had neared Cobh, they had been warned over wireless by the soldiers already ashore by U-boat: they could not land. There had been four destroyers in port and Tom Barry’s assault had failed. The ships had shaped course for Castletownbere only to receive an emergency warning from OKM in Berlin. The light cruiser Dauntless had been unexpectedly reactivated from the Reserve Fleet and decrypted signals listed the ship in Castletownbere taking on supplies, bound for the Mediterranean. With no hope of finding one of the Treaty Ports in friendly hands, the German vessels had been ordered to steam up Ireland’s west coast to Galway.

“And they’re landing there?”

Major Kohler hesitated, his mouth held slightly open.

“Yes,” O’Donovan hissed. “Word just reached Buncrana before I came up here.”

“Without the Free State’s permission?”

“Of course not. But nobody in Galway’s stopping ‘em either.”

“If German ships are being allowed into Galway as an open port,” Kohler said, “I fail to see the problem.”

“The problem, sir, is that we’ve just pessed away any chance of not having to fight other Irishmen in all this.” He ran a hand through his hair, gripping a great clump as if to pull it out. “The problem is that maybe hundreds of good men have been killed attacking fixed defenses for no reason.”

“I am sorry,” Kohler said, “but you must see that we have had no choice. If those ships had gone into Cobh, all would have been sunk. Surely you see this?”

O’Donovan nodded with great effort.

“I cannot pretend that these landings have gone without error. But it is fact that in Lough Swilly we have enough men to take Derry before the British can react. Enough men are in port at Galway -- one armored regiment and two infantry regiments, Hauptmann Auspitz -- that President de Valera would be very foolish to oppose us. Now our greatest worry is the security of Lough Swilly. British heavy ships are only a few hours of steaming from here, and it is essential that we have have working guns set up again before evening, and a good boom placed across the mouth of the lough early tomorrow. What is most important now is to have every available Irishman who will work on the defenses -- as many as you can find.

“Auspitz, you must gather as many fighters as you can, and join them with Russell’s main force of IRA men. Take as many as you can get in lorries and cars and speed straightaway for Dublin, telling the others to march across the country with all speed. The die is now cast. With or without Valera, you must go there and proclaim a United Ireland.

“Oberst von Bismarck hopes that before nightfall, 6. Schützen-Regiment will cross the border into Northern Ireland to screen your left flank and engage the British Army before they can be reinforced. It is just 100 kilometers from here to Belfast, and that will be the final objective of the panzers landing here. The loss of the panzers on the Stuttgart will, ironically, allow the remaining vehicles enough fuel to advance comfortably.

“Meanwhile, the men at Galway will race eastward to join you in Dublin. If the President can only be shown the solidity of the German position, he can almost certainly be induced to join with us.

“For myself, I must get a motorboat and cross to Portsalon as quickly as I can. General Hausser is about to come ashore.”

Chapter III: The Lion’s Den

Part XXXI

November 12, 1936

Fackel. Joseph Auspitz had been resting at the home of Moss Twomey, the Irish Republican Army’s Chief of Staff, when the daily signal from occupied France came over his radio. Fackel. Torch. The codeword signaled the Abwehr’s decision that a general uprising should begin in Ireland within a fortnight. That had been October twenty-eighth, and the intervening two weeks had seen final plans set in motion to rekindle the Old Resistance. Now, in just hours, the Second World War would at last break over the Irish Free State.

Auspitz huddled over his wireless set in a barn in County Donegal. He heard the new codeword a second time. Lauffeuer. Wildfire. The codeword for the general uprising to begin. Auspitz took down the rest of his instructions, then concealed his radio set. He walked out to the barn door where Seamus O’Donovan was having a smoke in the midnight air.

“It’s on.”

The IRA chieftain said nothing, but the end of his cigarette glowed bright red in the dark.

“Word from Germany is that they should have men ashore very soon.”

O’Donovan let the cigarette fall from his lips and stamped it out with the sole of his boot. “By sea or by air?”

“I -- I believe the plan is still by sea, and just the Treaty Ports. Even larger than we thought. I asked about Galway, but did not get an answer.” Auspitz was referring to the three ports in the southern twenty-six counties of Ireland that remained under British control. IRA men had spoken to members of de Valera’s government, and indications were good that he would not interfere with German operations against these ports insofar as they were of military value in the ongoing war. He might even be disposed to look the other way if the IRA participated directly. And so, Auspitz had been under intense pressure to obtain assurances that Germany would not take any action against the port of Galway, which belonged to the Free State. The Abwehr had not proven willing to make any such assurances, and Auspitz was highly skeptical of their motives in not doing so once Fackel had gone out.

“I just hope t’God they don’t. Would really sour Dev’s people on this.” When O’Donovan saw that the German was just as concerned as he was he nodded. “I’ll telephone someone who knows where MacBride is.”

Auspitz gave his assent. Seán MacBride, the center of their prearranged communications network, reportedly feared that Auspitz and his erstwhile colleagues in the George cell would betray members of the old Anti-Treaty IRA to de Valera in return for his government’s cooperation. He had refused to interact with the Germans other than through intermediaries, and Auspitz had consented to this treatment on O’Donovan’s advice. MacBride’s men, with their knowledge of the telephone and telegraphy networks, would were now poised to send the first nerve impulses of the Lauffeuer signal out through the country -- like wildfire.

Following sustained unrest in and around Belfast, including widespread and relatively successful IRA sabotage, the Abwehr had decided that the iron was hot. Better, they reasoned, to start the uprising in the south now, before the one in the north could be put down, and before any more of the British Army could be ferried from England. With luck, de Valera would see the situation similarly, and accept German assistance in driving British loyalists from the island like so many snakes. If anything was done to alienate him, the forces of the Free State would inevitably try to crush the IRA insurrection -- setting up a Second Civil War at odds that did not favor the guerrillas.

On the sixth of November, they had practiced the muster signal in anticipation of the real thing. From O’Donovan relaying the codeword to four thousand men gathering at their secret assembly points around the country was little more than two hours. If that speed was achieved tonight, the IRA brigades would be ready to assault the Treaty Ports two hours before dawn.

At Cobh, Tom Barry would lead a large number of men, many from County Cork, in an attempt to seize the most vital port on Ireland’s south coast. At Castletownbere, Jimmy Steele would lead a smaller raid to secure the town’s docks and neutralize its coastal defenses. The largest assault would come at Lough Swilly, just 10 kilometers to the north of the barn where Auspitz now stood.

According to reconnaissance, three Royal Navy vessels presently were sheltering in the lough. HMS Codrington, a modern destroyer armed with five 4.7 inch guns and eight torpedo tubes, would pose the greatest threat. HMS Halcyon, a minesweeper coming off repairs at Belfast, was docked nearby. Finally, a supply ship of unknown name sat at anchor near the town of Buncrana half way up the lough.

The plan called for O’Donovan and perhaps as many as 1,700 armed men to march into Letterkenny at the southern end of the lough, raising the alarm and trying to bring the police into the uprising. From there, they would race north and storm the Royal Navy’ shore installation and armory. Meanwhile, men would be trying to sink the ships in the lough with explosives. By now, with the hue and cry being raised throughout the county, more men would gather in Letterkenny to the sound of ringing church bells. O’Donovan would see to arming them with captured and spare weapons, then reinforce the eastern roadblocks set up by his cousin Ernan’s men to prevent British troops out of Derry from interfering. Meanwhile, Auspitz was told, fighters further up the lough would join small teams of German soldiers in disabling the defensive shore batteries, allowing the approach of the German ships that would firmly secure the port.

“The word’s going out, Captain.” O’Donovan was back. “A car’ll be here for us soon.” Auspitz noticed that the Irishman had a Soviet-made submachine gun slung over his shoulder and two bandoliers of improvised explosives across his chest.

“I hope,” Auspitz said sincerely, “that the police do not shoot you.”

“For their own sake,” O’Donovan grinned.

The Abwehr had been adamant that the uprising be carried off in such a way that the IRA not be brought into conflict with official Free State forces unless it was certain that they were offering resistance. In the critical first hours, the uprising was to present itself as a strictly anti-British popular movement. This presented a serious strategic difficulty -- planning Wildfire for both contingencies. That is, the insurrectionists had to be equally prepared to work with Éamon de Valera’s government if it chose to side with Germany against the British military, and to depose the very same government if it attempted to hinder the uprising. Experience told Auspitz that the result would likely be a patchwork of both eventualities.

A blacked-out automobile arrived with a driver and bodyguard and took O’Donovan and Auspitz overland to the tiny church near Cairn High on the west bank of the lough. A light was on in the belfry, and as the driver cut the engine and entered with O’Donovan, it was extinguished. Out came about a dozen fighters, heavily armed and with Ernan O’Donovan at their head.

“Y’remember Captain Auspitz, Ernan.” Seamus said as Auspitz stepped out of the car to meet them.

“Of course I do,” he said, lowering his Thompson submachine gun to shake the German’s hand. “Pleasure.”

Auspitz and the two O’Donovans agreed on a plan of action. Hauptmann Auspitz was to follow Ernan and his men to the cache of guns just a few kilometers to the north at Garrygort. Shortly after they got there, about 250 men were expected to converge on the area. They were to oversee the orderly distribution of arms and then march southward with all haste to Letterkenny, where they would meet Seamus’ larger force as it came up from the southwest.

Lough Swilly, County Donegal.

Up the narrow road they marched, kilometer by slow kilometer, keeping watchful eyes on the dark hills piled around them. Auspitz had the most formal training of any of them, but was in awe of the way they knew the country. With each step, Ernan checked the sounds of the night. These men could sense danger in these hills better than anyone -- Auspitz trusted their instincts far above his own.

They were nearing an intersection with a wider lane that had a ditch on the far side. All of a sudden, the men at the front drew to a stop at the same time. No one spoke. Auspitz listened, but the dead hours were still and silent. His mouth was dry -- it was dark ahead, he strained to see.

Something wasn’t right. Auspitz sensed a presence in the deep shadows of the roadside ditch ahead. He could sense that the other men were thinking exactly the same thing. The hairs on the back of his neck were standing up. Something wasn’t right at all.

“Ho!” Ernan raised the Thompson in the dark. All around, Auspitz heard the other fighters aiming their weapons into the gloom. “Ho!”

There was a moment of silence -- Auspitz couldn’t in his state of thunderous alertness tell whether it was ten seconds or less than one -- and then the sound of undergrowth crashing just meters in front of them. At the same instant, dark faces emerged from within the ditch and Ernan’s fighters bellowed calls to surrender. Somewhere to Auspitz’ right, a hunting rifle discharged, its muzzle flash illuminating a multitude of shining eyes in the ditch.

The next thing he was aware, Auspitz was leaning over Billy McCaughey’s bloody abdomen, trying to calm him as he applied pressure. The terrified boy couldn’t have been more than sixteen.

“Captain, captain!” Shouting as though from a great distance. An arm was tugging at Auspitz’ sleeve.

He looked up to find a knot of Ernan’s fighters nose-to-nose with men in German uniforms, on the verge of blows. Both sides had guns pointed at each other and were shouting in mutually unintelligible languages. One of the Irishmen was jabbing a thin-faced German with his sawed-off shotgun. Leaving Billy McCaughey to the care of one of his brothers, Auspitz physically placed himself between the two sides, begging for calm in both languages.

The strangers wore Heer uniforms but had faces painted black like minstrels, and wool caps instead of helmets. In German: “I am Luftwaffe Hauptmann Joseph Auspitz, here in Ireland as commandant of the Abwehr’s mission in the Free State. I want to know who you are and why you shot someone. These Irish are friendly.”

The man who had been jabbed with the shotgun turned to face Auspitz. “Oberleutnant Poch. Good. You take orders from the Army now. The invasion has begun.”

“You must at least give this man medical attention --”

“Not in the road.” Poch ordered two of his men to carry McCaughey into the field beyond the ditch where his men had been lurking.

Once they were out of the road, the Germans seemed to warm up, and two of them treated McCaughey while his worried comrades stood around him. Poch discussed the incident apologetically with Auspitz. It seemed that it had been McCaughey who had fired first into the ditch. One or two of the Germans, equally startled, and not fully certain as to the allegiance of these armed irregulars, had fired back in the direction of the shot. Poch’s goal was to stabilize the wounded man an get him to a friendly farmhouse, which could call for a doctor when they had departed. Did Auspitz know of one? He answered Poch that some of the Donegal men would surely know the land better.

The two conferred about the start of the operation. Poch said that he and his six men had been inserted by submarine, along with a raft full of explosives that he needed help getting safely off the beach. They would have to get up the mouth of Lough Swilly to disable the defensive artillery there. He fired off a battery of reconnaissance questions, most of which were different from the ones the Abwehr had told Auspitz to anticipate. When were the watch shifts at the base of the lighthouse? How far could the heavy coastal guns be traversed? Was there a ’round-the-clock guard on the Inch Island causeway? Where did the chief of police in Letterkenny live? Was the Oldtown Bridge stone or concrete? How deep was the water off Lenan Head?

Auspitz somehow managed to halt him. “Write down your questions, Oberleutnant, and I’m sure I can have someone get you the answers you need. For now, I just need some more information myself. Are your men alone?”

“No. Two other teams should have been put ashore somewhere in the lee of something called, I think -- no, it can’t, or -- something like ‘something-Head’.”

“Malin Head? That’s just north of the mouth of Lough Swilly. Is that it?”

“I think so. Two teams should have gone in on that side, but we haven’t heard from them since our submarines parted company at fiftieth parallel north. They could be delayed or lost, and we’ll have no way of knowing.”

Almost forty minutes had elapsed before they managed to get Billy McCaughey to a friendly farm and start out on their way north -- and for the narrow inlet where the Germans’ raft had been beached. Auspitz and Ernan agreed to send one of his men ahead to the cache at Garrygort while the rest helped offload the explosives, which, Oberleutnant Poch complained hotly, had been loaded far in excess of the realistic carrying capacity of his men. Ernan had been loath to risk the delay entailed in hours’ extra marching in the dark, but without taking out the guns that guarded the lough, the rest of the uprising in Donegal was doomed to failure.

They reached the raft without meeting anyone on the way, and trekked the explosives up near the mouth of the lough, where medium artillery had been emplaced at Knockalla. The guns here were not continuously manned, and so Poch’s men would simply rig their charges for detonation at 0500 and then proceed down the lough’s western shore to Macamish Point, where three smaller guns could be disabled with leftover explosives. Last would come the guns of Rathmullan, which would be destroyed just as the IRA fighters were beginning their assault. Carefully repeating the timetable to Poch, Auspitz wished him luck and led his men back south to Garrygort.

They arrived at the site to find no more than a hundred men, all of them milling about aimlessly and almost none of them armed. None of them seemed to have seen the runner they had sent ahead to open the cache.

“Where is he, Ernan?”

“I don’t know, Captain.”

Auspitz swore. “Then -- he -- he could have just gone off and betrayed us?”

“I know Bobby as well as anyone and he’s firmly with us.”

“But there is no other explanation. It’s been enough hours for --”

“Listen, Captain. Even if he has betrayed us, that doesn’t make any difference now. What’s on is on. Start handing out rifles.”

This undersized company was on the march southward by 0415 -- almost two hours behind schedule. They had not long passed the Cairn High church when the throaty rumble of demolition charges rolled over the still waters of Lough Swilly. Again and again the explosions sounded in the distance -- but rushing to a bluff, Auspitz saw nothing.

The rolling hills along the western shore of Lough Swilly.

About a quarter of an hour later, another set of charges went off, closer this time, and then silence. The sky was getting light by the time they came, after half a night of frantic marching in the dark, upon the fading lights of Letterkenny. Auspitz had half expected to see the town ablaze, or hear the sounds of gunfire, but he did not. The town looked almost peaceful as Ernan O’Donovan’s company descended from the hills.

They arrived unmolested at St. Eunan’s Cathedral, where Auspitz found Seamus and his lieutenants gathered, surveying the commanding view from the cathedral’s tall tower. The twelve great bells were pealing urgently, calling the muster.

“Only nine hundred, Captain,” O’Donovan said grimly as he gazed out over the lightening scene. In the blue-gray mist to the north, the minesweeper Halcyon sat inexplicably at anchor. “But more are coming. More may yet come to the sound of the bells.”

“We came into the town without being challenged, Seamus,” Auspitz hissed. “You must send men down to man the western and southern roads!”

The IRA chief didn’t lower his eyes from his binoculars. “With respects, Captain Auspitz, I d’n think you heard me. We’ve only got nine hundred men. Half of what we should. There aren’t men to block anything right now.”

“What about the police?”

“That’s the good news. The city is ours and except for a few fools, they’re staying out of the way. We’re mustering our next battalion all along Upper Main Street, down there --” he pointed a finger into the town center below, “while the nine hundred are marching up the eastern shore of the lough.”

“And the British?”

“That’s the bad news, but it could be worse. They’ve pulled back to Buncrana, including the destroyer. By how quick they did it, they probably had warning.”

“Now they can only be waiting for reinforcements from Derry,” one of Seamus’ men added, “and those can’t be long.”

“How many are there?”

O’Donovan sighed. “Several hundred men from the port, and a few hundred more regulars. They have us almost matched in numbers, and the advantage of the guns.”

“The guns? We heard the charges going off hours ago.”

“The destroyer’s guns, I mean. Out of the six main shore batteries, we’re mostly sure that four are down.” He pointed into the distance, sweeping his arm across the western shore of the lough. “Knockalla, Rathmullan and Macamish are blown, ninety percent certain, and we haven’t heard a pip from them. Unlikely that crews ever got to man them. The small guns on Inch Island -- that green mound that looks like a foreland of the eastern shore -- were destroyed, and we met the German saboteurs that did it. So we’re left with three hard places: the heavy nine-inchers at Lenan Head, the fort at Dunree and the medium guns all around Buncrana.”

“You never heard explosions from those positions?”

“Oh no, we did. But we’ve also heard the fire of heavy guns from that direction. We don’t have anything that heavy.”

It was after seven, and the sun was just shearing through the dawn mists to the east of Letterkenny. “How many men does Ernan need to hold the road from Derry?”

“Two hundred, at least. That’s enough for a delay, at least.”

Auspitz sized up the eastern ground. “Then give him a hundred, and two of the heavier machine guns. Everyone else is to form up with me at the Courthouse and then march up north. The battle will be at Buncrana.”

“Jack, Tom, Johnny,” O’Donovan said to the lieutenants around him, “do as Captain Auspitz says.”

It was not long before Ernan was sent east with a hundred men to block the way of any force force from over the border in Derry, while Auspitz scraped together as many men as he could to reinforce the nine hundred already headed for Buncrana.

Precious minutes of initiative passed as IRA fighters trickled onto Upper Main Street in nothing near the sense of hurry Auspitz thought warranted. He exhorted the officers to get them going. If the guns of Buncrana weren’t silenced -- to say nothing of the long guns at Lenan Head -- the German ships coming into the lough wouldn’t stand a chance.

“Message for Cap’n Spitz from Mister O’Donovan, sir!”

Auspitz whirled. A blue-eyed boy of twelve had sidled up behind him. “Yes?”

The boy handed him a scrap of paper.

Castletownbere report poor. Steele dead. RN cruiser holds port. --O’Donovan

Biting his lip, Auspitz scrawled off a reply.

Any word on Cobh? Am going to Buncrana. Telephone Twomey for reinforcements. --Auspitz

The boy darted back toward the cathedral with the message, and Auspitz turned to the IRA officers around him.

“Head-count?”

“We can probably get four hundred if we --”

“Not probably! How many men are on the street right now?”

Counting took several minutes. “Two hundred and fifty or so.”

These were the most dangerous few hours of the entire uprising. Further delay, Auspitz knew, could prove fatal. “Form them up!”

With Auspitz at the head, 213 men set off double-quick on the three hour march up the shore of the lough to Buncrana. They proved to have excellent stamina, and the German found himself taxed trying to keep up. He slipped up and down the column, inspecting the arms of the fighters -- at least half had automatic weapons, he was immensely pleased to see, but ammunition was short. The fastest men he posted as screens ahead of the column to deter ambush, but none materialized on the open road winding through the hills east of Lough Swilly.

Lough Swilly, seen from the south, looking out over Inch Island.

Just after ten, the sound of gunfire became audible ahead, and Auspitz ordered his ad hoc company into a skirmish line. Cresting a wooded bluff, they saw the battle a few hundred meters below.

About a hundred British regulars were dug in around an apple orchard outside the town of Buncrana, trading fire with a large mass of IRA fighters spread across a gentle stony slope.

Auspitz turned to his men. “Hold here.”

He sprinted down the slope, weaving between Irishmen as the enemy raked ground around him. He picked out O’Cannon, the leader of the force, and ducked behind a boulder not far from where he was standing. The air was full of sharp rifle cracks and grumbling bursts from the Irish submachine guns. From his position he could see two Irishmen fallen in the road, and another slumped against a tree. White smoke hung over the Irish lines.

“O’Cannon!” Auspitz cupped his hands to his mouth. “O’Cannon!” Louder: “O’Cannon! Come here!”

The forty-eight year old son of ancient nobility broke from his cover behind a tree and ran to the German’s side. “Captain?”

“Yes. Listen -- the way those marines are shooting, you’re never going to win like this. They’ll just wear you down. Do you understand me?”

“Yes.” His proud blue eyes belied serious leadership deficiencies. Unused to pitched battle, he had done perhaps the worst possible thing, and gotten his men checked by a force they outnumbered almost ten to one.

Auspitz pointed up the slope. “I have two hundred good men with me. Listen -- you are pinned down right now -- you cannot advance without getting shot up. I do not want you to advance. I want you to get your men ready to all fire at once. I will take my men into that sunken lane over there. We will get around the side of the orchard, where the road curves by that yellow farmhouse. Do you see that?”

“Aye.”

A fighter standing next to the boulder screamed in pain and crumpled. “Look at me, O’Cannon! I want each one of these men to start shooting as soon as you see us reach the yellow farmhouse. You’ll be able to see us as we move toward it. Once we’re there, shoot like a devil into the orchard to keep their heads down. This will allow us to come around and get them.”

“Aye. I’ll tell the men.”

Auspitz scrambled back to the crest of the slope and relayed the plan to his company. They jogged into the sunken lane, keeping their eyes on the yellow farmhouse half a kilometer ahead.

“Go! Go!” The company broke into a run, following the curve of the road around the farmhouse and emerging into an empty field next to the orchard. The men on the slope slope came alive with supporting fire. Auspitz unslung his MP34 and pointed at the crouching figures ahead. “At them! At them!”

The men rushed forward, firing hotly at the already-engaged British. Some tried to break into the road and and flee to the west, but most of these were cut down in the crossfire. The blistering firefight lasted less than a minute, and when it was ended, Auspitz counted just four dozen British soldiers still standing. Directing the dazed surrenders under guard to the rear, he ran to rejoin O’Cannon as he brought his men down the slope.

Congratulations were brief. “What we must do now,” Auspitz told him, “is to storm the town of Buncrana itself.”

Although the men were already exhausted from a speed march from Letterkenny, they would have to assault Buncrana and its coastal artillery quickly. The HMS Codrington was loitering just off the docks, and with its large guns could decimate the Irish as they crossed a 900 meter wide exposed greenbelt outside the town. Once they were in the town, they would be protected from the destroyer’s guns and too close to the defenders for the Codrington to be able to fire on them safely.

An automobile horn oogahed as its driver nudged through the dazed fighters toward the two conferring leaders.

Seamus O’Donovan stepped out. He congratulated O’Cannon warmly for the daring assault before turning to Auspitz. “No word on how the battle for Cobh is running. But two pieces of good news. First is the Lenan Head and Dunree guns were blown up. Eight lorries of our boys and the Carndonagh lot took ‘em down along with some Germans. Just like we thought, most of the gunners are quartered farther to the south, and ‘cept for a few hot exchanges, the boys almost walked right in. ‘Parently the gunners who were there got nervous, though, and shot up a neutral ship in the mouth of the lough before it was all over -- we’ll see to that later. The second bit is that I’ve got near two thousand more boys coming up the road now under Seán Russell.”

The German raised an eyebrow.

“Five hundred are veterans, he says, and the rest are just eager. Most of them aren’t armed, anyhow. The first of them will be here in an hour.”

Auspitz checked his watch. That means a little before noon. “Fine. But I want you to make sure Russell follows our plan of attack.”

Russell’s motivated column arrived a quarter of an hour ahead of schedule and he immediately joined Auspitz, O’Cannon and O’Donovan on the slope overlooking Buncrana.

Auspitz drew up the attackers into three formations. O’Cannon would lead the inexperienced men -- almost two thousand in all -- and lead them around to the northern side of Buncrana. O’Donovan and Russell would each lead several hundred of the hardened fighters -- the former from the south and the latter from the southwest -- and cross the greenbelt under fire. They would take casualties, Auspitz said, but both commanders knew that their men could take them and keep going. O’Cannon, of course, insisted that his own brigade could fight to the last.

“Yer problem is that you’d give them a chance to do it, Tom,” Russell scowled.

“Gentlemen.” Auspitz turned back to the map he was drawing in the soil with a small branch. “Seamus from the south and Russell from the southwest. You must get across the open ground fast, and fight those marines where the destroyer can’t support them. Once you are pressing them strongly, O’Cannon’s larger force sweeps in from the north --” Auspitz drew a large X over the British defenses, “-- and overruns them. Meanwhile, I want to get every heavy machine gun from your men. They’ll have to move too fast to set them up anyway. I want you to set up a base of support fire in that long stand of trees over there. It’s out of the destroyer’s line of fire but is in a good position to lay fire on the town. Is that agreed?”

It was. At 1307, O’Cannon’s force signaled readiness from its position just north of Buncrana. Auspitz ordered the machine guns to lay fire into the town, and with a great shout, more than seven hundred of the IRA’s best fighters charged out onto the greenbelt and under the guns of the HMS Codrington.

At once, the destroyer started firing, its powerful shells tearing great clouds of Donegal’s black soil into the air. The Irish were lifelong skirmishers -- they spread out naturally and moved across the killing zone quickly, but the Royal Navy guns would not be denied. Dozens fell, never to rise, as the Codrington gouged terrible holes in the IRA lines.

After four long minutes, they surged among the neat, whitewashed houses of Buncrana, and the town came alive with a stunning volume of gunfire. At once, the Codrington’s battery fell silent, its sailors watching the battle with the same interest as Auspitz himself.

White smoke hung over parts of the town, marking roughly where the fighting was thickest. Fifteen minutes passed with no headway made. “Signal O’Cannon to attack,” Auspitz instructed, sending a man further up the slope with semaphore flags.

As Tom O’Cannon’s men swept in from the north, they too were checked by the British defenders.

With nothing else to be done from his position above the town, Auspitz and the IRA officers with him crossed the greenbelt on foot to join their men and perhaps influence the decision in person. When the German reached the fighting, several dozen of Seamus’ men were in a brisk firefight with the British defenders of a merrily burning grocery.

The Irish would duck out from cover to fire shotguns, pistols or Thompsons into the ruined store, and every few seconds a yellow flash strobed deep within as a machine gun spat a reply to keep the attackers at bay.

As Auspitz watched from behind a corner, one of the fighters ran forward with an improvised fuel bomb. Bullets kicked up the dirt around him, but he managed to reach the grocery’s outer wall and press himself against it. Without looking, he hurled his gasoline-filled bottle deep into the store and sprinted back towards his comrades. The glass bottle shattered, and the burning rags stuffed into its neck set the gasoline alight in a splash of orange flame.

Instinctively, Auspitz ducked around the corner and began firing his MP34 into the blazing maw of the store. “Go in! Go in!”

As he covered them, six fighters stormed in and returned signaling what they had seen inside. The defenders were dead.

They inched further up the street, watchful of every door and window, following the crackle of enemy gunfire. Men lay dead in the road, most of them Irish, surrounded by the white-gray powder that had been shot from the pockmarked buildings.

They climbed over a broken fence and emerged into an open yard between the cemetery and the side of the protestant church. Both sides were trading fire in the street, as two machine guns in the vestibule kept anyone away from the entrance. Firebombs had hit the stone walls in several places to little effect, leaving only great black scorch marks and smoldering clumps of grass below.

Christ Church, Buncrana, County Donegal.

Auspitz caught a flash of movement in one of the darkened windows and threw himself to the ground just as a stubby barrel poked out and began spraying the field with automatic fire. One of his men screamed that he had been hit. Rolling onto his side, Auspitz fired an entire clip at the window and scrambled behind a parked automobile a few meters away to reload. Two fighters were already there, also reloading.

“I think I might have knocked out the machine gun. When I say, I want you to start come out from --”

The windows behind him exploded in a renewed staccato of gunfire. All three men sheltering behind the car crouched as low as they could, pressed against its black body, just as the dull think of bullets pounded against the doors on the other side. One of the tires blew, and the next moment the gun fell silent.

“When I say --” Auspitz paused, expecting the the shooting to start again, “when I say, I --”

A sharp burst of gunfire slammed into the car again, rocking its entire body and showering Auspitz with broken glass. More fighters out of his line of sight screamed, hit. The Irishmen were firing back, but probably blindly and from cover.

Auspitz dropped to his stomach to look out from under the car. A water-cooled machine gun was raking the field in wide arcs. A man with a shotgun appeared from behind a large headstone in the cemetery and fired straight at the window. A shower of wood and brick erupted around the window-frame -- but the machine gun reopened fire before Auspitz even had time to hope that it had been silenced, battering the words from the headstone’s face as the shooter sheltered pitifully behind it.

He turned to the men next to him. “When I say, I want you to shoot right into that window for as long as you can.”

Misunderstanding, the nearer of the two leapt up at once and started squeezing off rounds from his old revolver. Auspitz pulled him down by the legs just as the man attracted the attention of the machine gun. It must have fired fifty more rounds into the stricken car, as Auspitz pressed his face into the earth for protection.

A tinkle and the loud whump of deflagration told him that one of the Irishmen had at last gotten close enough to lob a firebomb. Overwhelmed by the smell of burning gasoline, he held his breath and jumped up from cover to see flames pouring from the church window.

He shouted for the others to follow him, but they needed no encouragement. Several men charged forward and forced open the side door. Auspitz ran after them, his submachine gun up, through the doorway and into the church -- stepping over a wounded man and spraying the packed sanctuary with bullets.

He heard another tinkle and felt the roar and heat of a fireball slam into his back and throw him to the floor. As the smoke cleared, Auspitz pulled himself to his knees. He found at least twenty Irishmen inside the church, pointing their guns at a much larger number of British, many of whom didn’t seem to be soldiers. Their hands were up in surrender.

Auspitz joined O’Donovan, O’Cannon and Russell on the dazed street in front of Christ Church. The German’s ears rang, but he was almost certain that the gunfire was over.

“The destroyer’s pulled off and gone up a quare way toward Lenan Head along with the minesweeper,” O’Donovan said, dabbing a bleeding cheek with his sleeve. “Some of our boys got to the guns near here and managed to fire a few times. Made them nervous. Do you think the guns should be blown up now?”

“If you’ve got men who served on them in the last war, and can work them, no. But if you cannot put them to use, we ought to blow them.”

Aside from two of the guns, which had ready ammunition, the rest had none to hand, and so were ruined with explosives. As soon as the town was confirmed to be secure, Russell and O’Donovan agreed to detach O’Cannon and most of the non-fighters who had marched up with Russell southward -- there to keep order in Letterkenny and reinforce Ernan’s tiny contingent on the Derry road.

The aftermath of the Battle of Buncrana held a great surprise. Although the IRA men had at first appraised the enemy as nearly a thousand strong -- and had sent out a proclamation of defeating such a number -- it was not nearly so. Between the Battle of the Apple Orchard and that for Buncrana itself, they had faced no more than three hundred armed British. Although gravely outnumbered, their training had come to tell. Not thirty of them had been killed, in exchange for nearly a hundred IRA dead or about to die.

As the women of Buncrana came out to tend to the injured, a car trundled in from the north, with an urgent request for Auspitz to go north to Dunree. Legs numb from hours of marching down one side of the great lough and up the other, he slumped agreeably into the back seat. They drove north along the shore of the lough, two fighters hanging onto the runners for protection. The point at Dunree Head jutted up like a ship’s prow in the waters of Lough Swilly, crowned by a small fort first built to keep a different Continental enemy out of Ireland -- Napoleon. The car came to the top of the hill, and Auspitz shook his head at the strange sight.