Pharaoh hardened his heart

XIV – Makes you think

1703, on the slopes of Mount Jordan, near Sidon

“Just look at them.” Mercato said.

Captain Jacopo di Pazzi was already looking at them, a hundred bare-chested brown men exercising silently in the still cold morning, under the example of their own captain.

“Makes you think.” He finally said, rather to put an end to the silence than anything else. Even since the Egyptian Army had joined them he kept his word guarded. No use ending up like his grandfather’s uncle. And of course, for all they knew, the Egyptians had saved them from a complete rout. When they'd seen the new army the Greeks had stopped right where they were, two days before.

“Timeo Danaos et dona ferentes. Both objects need not be the same.”

“What’s that?”

“Timeo Danaos et dona ferentes. It’s from the Aneid, something Aeneas says.”

“Yes, I kn… It’s not even Aeneas! It’s Laocoon.”

“Technically it is Aeneas, because it’s a story within a story, so Aeneas says it even if he repeats Laocoon’s words when he tells his tale to Dido.”

“… Ok, fine, what’s your point with both objects?”

“See, the second ‘Danaos’ is implied, so it means ‘I fear the Greeks and even when they bear gifts’, the Greeks, right?”

“Right.”

“That’s the conventional reading. But it might just as well read ‘I fear Greeks, and also those who bear gifts’, meaning not the Greeks. If it was out of context.”

“… I guess.” He turned his gaze again to the magnificent men lined up in silent effort.

“You see who I mean?”

“YES.”

Zealots, in Pazzi’s experience, made poor soldiers. They thought fervor made up for recklessness or disorganization or even worse traits. They did not take well to orders from this world. And they always stuck together, so there was no rooting the weak and the bad from their ranks. Good fighters, sometimes, but as troops, pretty bad. These ones were different, not hot-headed at all, quite the contrary. Stone cold fanatics. Egyptians Jihadi kept themselves and their camp clean and in order. They did not gamble, drink, or brawl, although they did smoke from collective hookahs. They did not leave their camp, except on business, and when an Italian tried to get in theirs and see what was what, they made it clear he was unwelcome. And now that. Lifting weights in the cold of the early morning.

“Could you do that?” Mercato asked. Even from a friend, it was a little unkind.

“I think so,” Captain di Pazzi snapped.

“I mean make your men do that. Every morning, without noise, without complaints.”

“They’d kill me.” Pazzi was the closest thing to a father his men had and, for most, had ever had; but they were still scum from the gutters of Venice. Deepest gutters in the world.

“Me too.”

At this point he could see a rider hurrying toward the camp from one of their advanced positions.

“I’d better take care of that.”

The rider saw an officer coming to meet him and changed his course. When he was near he shouted without dismounting: “The Greeks ! They are moving.”

“Which way?”

“South-east. They are trying to turn the mountain by the East, give us a wide berth. Slowly. A screen of outriders around the main force.”

“I’ll tell the council. Make sure another rider is ready to depart right here with a fresh horse, and then go get some rest.”

He turned and jogged to the General’s tent, through the bestirring camp. Every sentry had seen the rider now, and confused and contradictory rumors would run through the army. As long as they readied themselves.

When he entered the command tent other officers were hurrying in too. It had been a little crowded at the beginning of the campaign, when all sixty captains and majors and colonels gathered to get orders; but now there were four-and-twenty less, and they could almost breathe. General Umadbro was sitting at a table with what few maps they had of the region, on top of which hostile and friendly troops were represented by pieces commandeered from a cheap chess set. At his side a D.R.A.G.O. intelligence office bit his lip nervously. But it was Pharaoh, sitting on the other side, who spoke.

“… So it is good I came here. It means the position of C.U.C.K. forces is untenable without adjustments.”

Pharaoh, whom Captain di Pazzi had seen before, but never so close, was a big dark man in a clean but simple white linen tunic. Only grey hair in his braided beard showed his age. His poise was confident, his naked arms bulged with impressive muscles, and behind his hooked nose fierce black eyes burned with commanding power. Pharaoh was born to lead men; in fact it almost seemed men were born to be lead by him.

Pharaoh coming in the person at the head of his Holy Warriors to crush the Grecian counter-attack

“Greeks move this way,” he said, nudging a black rook. “And this way.” His big black fingers closed on a black pawn.

Captain di Pazzi almost cleared his throat, and then he realized Pharaoh was already giving what information he had. Did the Egyptians have sentries of their own? Outriders, maybe?

“… Screen of cavalry. So, what do we do.”

“As you know,” General Umadbro said, “Our men have yet to recover from the previous clashes. They will fight,” he insisted, “but not as well as fresh troops.” Egyptian troops went unsaid.

“Yes. I have studied Byzantine strategy for a long time. They never truly commit; they always hedge their bets. This is a prodding move. When they meet fierce resistance, such as my men will provide, they will not try to break through but retreat carefully to a more secure position.”

For the first time Captain di Pazzi realized Pharaoh was not only speaking in Italian, but with the nasal lilt of his Trentine mother, the yokel accent he himself had spent ten painful years scouring from his tongue. What was that? An insult?

“We must take advantage of this predictable development. While my shock troops make a stand down in the valley, yours will deploy in a thin line high on the slopes of mount Lebanon, protecting your artillery far to the left, with a full view on the battlefield.” A show. He was giving them a show. “Once they fall back your artillery will start pounding them from the side, denying them the opportunity to make an orderly retreat.”

“Apologies, your Highness, but if we spread that thin, could they not turn and overcome us.”

“If they turn we will take them from behind. This mountain is young, the slopes only increase as you go up. Which means a pursuing army will always catch us with the pursued one.”

This mountain is young? What the hell did that mean? But the General nodded, pretended to hesitate briefly, then hung his head in complete submission.

“Do it.”

They filed out of the tent hurriedly. Mercato touched Captain di Pazzi’s elbow.

“You did not say what the rider was about.”

“He already knew.”

The cannon master smiled with a hundred meanings.

“…Et dona ferentes.”

“Wait, I thought it was at the beginning, before he meets Dido. That’s why everybody quotes that, because it’s at the beginning.”

“Aeneas meets Dido at the beginning. Then he tells her what happened, that’s the point of having a story within a story.”

“You’re sure it’s not the Odyssey?”

“Dido is not in the Odyssey.”

“I KNOW! I mean the story within the story.”

“All stories are within stories. Makes you think.”

Mercato could be really exasperating when he put his heart into it.

“Just get your cannons ready. We’re going to see a show.”

“Beside that one, you mean?”

Below them Egyptian soldiers were filing out, singing hymns of a sort in their strange tongue and perfect harmony. Captain di Pazzi did not understand everything but he could make out some fragments: “One god, in a thousand aspects”; “from the darkness beyond our world” ; “always watching” ; “one faith, one people”; “the blood of the unbeliever”.

“Yes. Beside that one.” It will be a long day.

But at the end of the day, they won. Or did they?

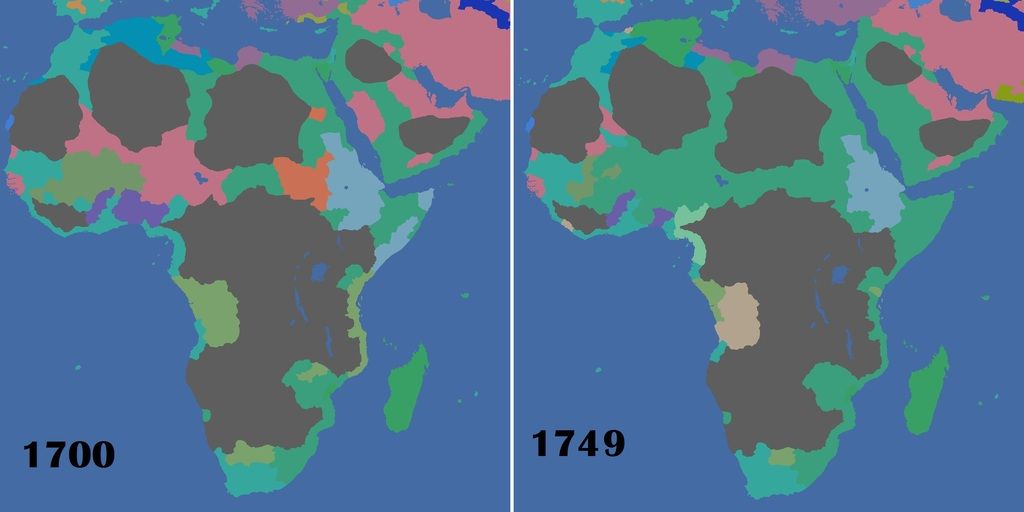

I conquered all of the Hejaz region in former Persia. Now that I’m an empire (oh yes, I’m a n empire now since… two weeks?) Arabic culture group provinces are yum-yum to eat.

I also completed the religious idea group, converted all remaining kafirs quickly and started the slower process of cultural unification.

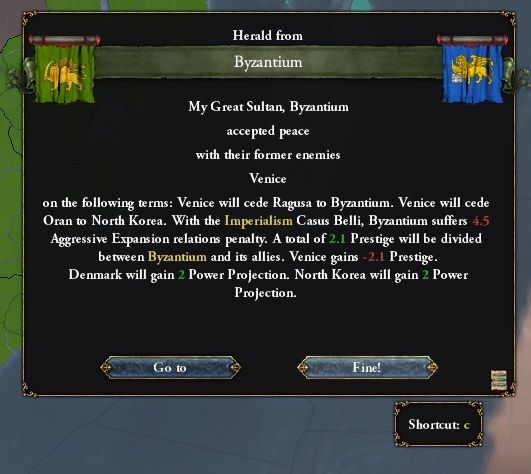

Then the Cooperative Union of Central Kingdoms (Germany, Venice and Egypt) responded to Byzantium’s provocations by attacking it with Fox’s help. England and Denmark intervened on Byzantium’s side...

... and it became a true world war with multiples fronts:

• On the Syrian front the lack of maneuvering space forced a stalemate at the single province of Sidon. Many times Grecian forces tried to retake the fortress from Italians but the intervention of Pharaoh himself and his elite troops threw back that meek and effete rabble.

• On the Mali, on the contrary, it was the vast distances of immense undeveloped bush that lead to and indecisive campaign. Me, Fox and Baron all tried some half-hearted maneuvering that came to nothing.

• In the Americas, Fox triumphed unopposed. But the struggle was not to be decided there.

• In the Baltic Germany made small progresses but I did not pay much attention.

• In Maghreb, the bulk of the Egyptian army secured Byzantine Lybia and Venitian Atlas. But then English started pushing back, at offs of three to one or more. After a valiant resistance and one successful counter-offensive, Egyptian forces were finally routed when reinforcement from Best Korea sailed half a world to victimized me. Egyptian troops started on a desperate and xenophonic flight home, behind the cover of forts and deserts and mountain.

• Finally, it was in Italy that the back of the Union was broken. England conquered everything and even started breaking through the Alps in Jakob’s backyard. At that point resistance was futile.

So we surrendered. At least lucky Kuipy dodged the bullet, only Germany and Venice had to pay up.