The Queen of Cities: A Byzantine AAR

- Thread starter RossN

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

And once again the Empire reclaims territories long lost to previous invaders. Glad to see some measure of stability returning to the Balkans, although the death throes of Bulgaria are somewhat lamentable (if only because they herald the end of a potentially useful buffer state).

It sounds like the Byzantines might finally have attained some measure of peace and stability, though if I know either this game or typical Byzantine history, it won't be long before something dramatic shatters that moment of respite.

It sounds like the Byzantines might finally have attained some measure of peace and stability, though if I know either this game or typical Byzantine history, it won't be long before something dramatic shatters that moment of respite.

Any plans in the future to go beyond the Danube? Or do you just intend to rebuild the Roman Empire, or...?

I really thought the Autokrator Kyrillos was going to convert the Bulgars to Roman rule. Battle of Manzikert -Byzantine defeat - that's a yes we know, do not fight battles there. I think you are doing really well. You have had a shed load of luck with the Abbassids flunking their existence like that. You've a century before the Pechnegs and Seljuks show up, though you're right on the verge of the Rus trying to take Constantinople - it's after they've destroyed the Khazars. I think your retinue is just slightly too small to effect a conquest of Alexandria and you've probably gone through the survivors of that rebel army that one of your Emperors inherited.

Hungary is not a threat, the Frankish successor states have no direct border with you and a fellow Orthodox Georgia rules the Caucasus. Time to go back to the Levant... perhaps even as far as Aegyptos?

Measured, steady expansion. Adrianos seems to have the luxury of choosing his wars, and how much of his might he wants to commit to them. An enviable position to have (and I doubt it will last long enough  ).

).

Does Adrianos have any grand goals he is trying to achieve, or are his conquests more a matter of expediency?

Liked that little tidbit about the crushing Roman defeat lowering the price of slaves in Damascus.

Does Adrianos have any grand goals he is trying to achieve, or are his conquests more a matter of expediency?

Liked that little tidbit about the crushing Roman defeat lowering the price of slaves in Damascus.

I like your roleplaying with the religious conversions. It's something I never even thought of in my AAR.

Part Four - The Aleppon War

With the decline of Damascus and Antioch only beginning to regain her former glory Aleppo was perhaps the richest, largest city in Syria in the second half the 10th century. It was an old city, known as Beroea to the Greeks. Aleppo was built on eight hills and surrounded by stony ground but close to the fertile plains. It's wealth derived less from this than from the eastern trade which from time immemorial had passed through her gates on the way to the Syrian coast. In Roman times it had been an important Christian city and even today contained many Christians but by the age of the Emperor Adrianos II it had long since become a centre of Muslim power. The Emirs of Aleppo had maintained a precarious independence from the Abbasids (and later the Muradids) for over a century relying on wealth and diplomacy to steer would be conquers elsewhere.

The current Emir was Abdul-Razzaq, derisively known as 'the Ill-Ruler' by his subjects. Abdul-Razzaq had intervened in the Antiochene War in the late 950s, thereby earning Roman emnity. The Emperor had been in little position to punish him then but by March 968 the situation was very different. The Balkans were quiet and Adrianos could return his attentions to the East. He was glad to do so as very recently the Muradid Caliph had transferred his court from distant Dwin to the Syrian port of Tripoli. The concern in Constantinople was that Faruk (or rather his regent) was planning to annex the upstart emirate once and for all.

Relations between Constantinople and the Muradid Caliphate were complex. Murad himself had been the great foe of the Abbasids and though there had been no formal alliance with the Romans there had been a certain understanding. After his death and the minority of Caliph Faruk Adrianos had opened up relations with the new Caliphate. The Emperor was concerned with reopening the lucrative trade with Persia and Egypt which had all but ceased in recent decades and securing the safeguards of Christians in the Levant. The establishment of the great Muslim court at Tripoli turned the Muradids focus from Armenia and the Caucasus and towards Syria and the Mediterranean and in 967 the first Roman envoys had arrived in Tripoli. At the moment the two great states were relatively friendly rivals but Aleppo had the potential to upset all that. Therefore Adrianos did not move against Abdul-Razzaq until he reached an understanding that Tripoli would remain neutral.

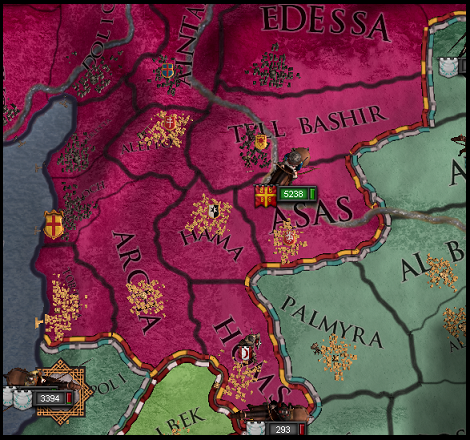

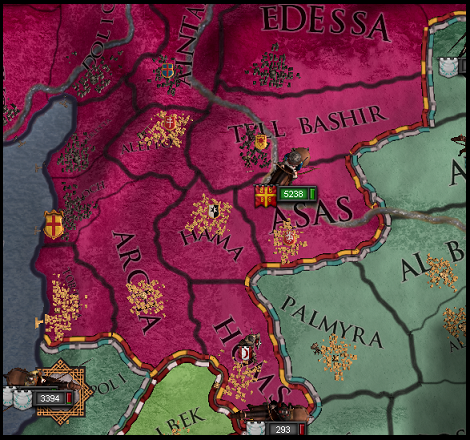

The war against Aleppo that started in March 968 was swift and bloody and the Romans quickly overran the Emirate and took the cities by was storm. Led by Captain Leon of the Varangians the Roman army also included the Kataphraktoi retinues and levies from the Asian themes. The Emir had hoped for help from Tripoli and wrote desperate letters to the boy Caliph but Faruk took no action and sent no reply, uninterested in fighting the Romans for the sake of an Emir who flaunted his independence. The Muradids were the only power that might seriously trouble the Romans. Without their aid the outcome was inevitable. On 29th September 968 Abdul-Razzaq signed a peace that left him with just Baalbek. Asas, Homs, Hama and Aleppo itself all passed to the Romans. Suprisingly while Adrianos chose to keep only Homs under his personal control, appointing noblemen to rule in the other three counties. Homs was strategically significant and Adrianos began construction of a new city nearby, intending to plant a colony of Greek speaking Christians that would bring the ways of Rome to this corner of Syria. He oversaw the start of work personally.

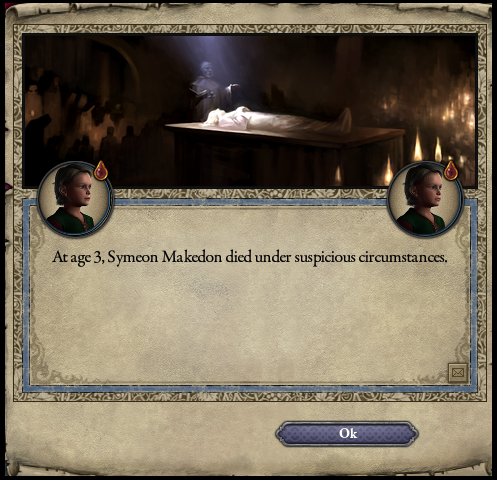

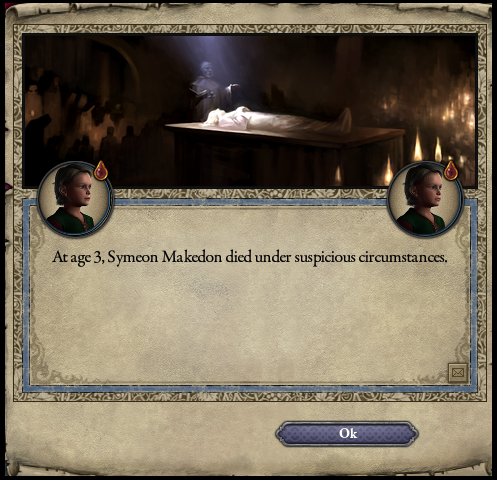

The Emperor had a good reason for being out of Constantinople; he was consoling his grief through work. Over the past year there had been three deaths that lay close to his heart. The death of the Caesar, Robin of Amalfi and the Sakelaris Count Laurentios of Euboea was hard but not unexpected; both men were elderly and had served the state for literally decades. Far harder to deal with was the strange death of Adrianos' three year old son Symeon on 23rd June 968. The young prince seemingly died from suffocation after accidently trapping himself in a chest while playing but doubts quickly emerged that he would have been strong enough to lift the lid open in the first place. The eunuch charged with guarding him had disappeared mysteriously the same day so could not be questioned. A few days later he washed ashore on the Golden Horn, his throat slit from ear to ear.

Historians since have strongly suspected the prince was killed but not one shred of conclusive proof has ever emerged about who might have done the deed[1]. While there were several who might have profited from the deed suspicion focused then and now mostly on Adrianos' younger brother Symeon, Doux of Adrianopolis who now became heir, a position he had lost after the birth of his nephew and namesake. Adrianos refused to believe the public suspicions, unable to believe his brother might have been involved but the Empress began pushing for the law to be changed so that their daughter Theodora would ascend to the purple and managed to persuade her husband not to appoint Doux Symeon Caesar after Robin died. As both Adrianos and Eusebia were still under thirty it was hardly impossible they would have another son, but if they did not the succession might become problematic down the road...

The unsolved death of Prince Symeon.

[1] I don't know who did it myself. I suspect Doux Symeon but there are other would be claimants to the purple who haven't always been scrupulous.

The Emperor Adrianos II recieves an embassy from the Muradid Caliphate.

With the decline of Damascus and Antioch only beginning to regain her former glory Aleppo was perhaps the richest, largest city in Syria in the second half the 10th century. It was an old city, known as Beroea to the Greeks. Aleppo was built on eight hills and surrounded by stony ground but close to the fertile plains. It's wealth derived less from this than from the eastern trade which from time immemorial had passed through her gates on the way to the Syrian coast. In Roman times it had been an important Christian city and even today contained many Christians but by the age of the Emperor Adrianos II it had long since become a centre of Muslim power. The Emirs of Aleppo had maintained a precarious independence from the Abbasids (and later the Muradids) for over a century relying on wealth and diplomacy to steer would be conquers elsewhere.

The current Emir was Abdul-Razzaq, derisively known as 'the Ill-Ruler' by his subjects. Abdul-Razzaq had intervened in the Antiochene War in the late 950s, thereby earning Roman emnity. The Emperor had been in little position to punish him then but by March 968 the situation was very different. The Balkans were quiet and Adrianos could return his attentions to the East. He was glad to do so as very recently the Muradid Caliph had transferred his court from distant Dwin to the Syrian port of Tripoli. The concern in Constantinople was that Faruk (or rather his regent) was planning to annex the upstart emirate once and for all.

Relations between Constantinople and the Muradid Caliphate were complex. Murad himself had been the great foe of the Abbasids and though there had been no formal alliance with the Romans there had been a certain understanding. After his death and the minority of Caliph Faruk Adrianos had opened up relations with the new Caliphate. The Emperor was concerned with reopening the lucrative trade with Persia and Egypt which had all but ceased in recent decades and securing the safeguards of Christians in the Levant. The establishment of the great Muslim court at Tripoli turned the Muradids focus from Armenia and the Caucasus and towards Syria and the Mediterranean and in 967 the first Roman envoys had arrived in Tripoli. At the moment the two great states were relatively friendly rivals but Aleppo had the potential to upset all that. Therefore Adrianos did not move against Abdul-Razzaq until he reached an understanding that Tripoli would remain neutral.

The war against Aleppo that started in March 968 was swift and bloody and the Romans quickly overran the Emirate and took the cities by was storm. Led by Captain Leon of the Varangians the Roman army also included the Kataphraktoi retinues and levies from the Asian themes. The Emir had hoped for help from Tripoli and wrote desperate letters to the boy Caliph but Faruk took no action and sent no reply, uninterested in fighting the Romans for the sake of an Emir who flaunted his independence. The Muradids were the only power that might seriously trouble the Romans. Without their aid the outcome was inevitable. On 29th September 968 Abdul-Razzaq signed a peace that left him with just Baalbek. Asas, Homs, Hama and Aleppo itself all passed to the Romans. Suprisingly while Adrianos chose to keep only Homs under his personal control, appointing noblemen to rule in the other three counties. Homs was strategically significant and Adrianos began construction of a new city nearby, intending to plant a colony of Greek speaking Christians that would bring the ways of Rome to this corner of Syria. He oversaw the start of work personally.

Syria in 969 AD.

The Emperor had a good reason for being out of Constantinople; he was consoling his grief through work. Over the past year there had been three deaths that lay close to his heart. The death of the Caesar, Robin of Amalfi and the Sakelaris Count Laurentios of Euboea was hard but not unexpected; both men were elderly and had served the state for literally decades. Far harder to deal with was the strange death of Adrianos' three year old son Symeon on 23rd June 968. The young prince seemingly died from suffocation after accidently trapping himself in a chest while playing but doubts quickly emerged that he would have been strong enough to lift the lid open in the first place. The eunuch charged with guarding him had disappeared mysteriously the same day so could not be questioned. A few days later he washed ashore on the Golden Horn, his throat slit from ear to ear.

Historians since have strongly suspected the prince was killed but not one shred of conclusive proof has ever emerged about who might have done the deed[1]. While there were several who might have profited from the deed suspicion focused then and now mostly on Adrianos' younger brother Symeon, Doux of Adrianopolis who now became heir, a position he had lost after the birth of his nephew and namesake. Adrianos refused to believe the public suspicions, unable to believe his brother might have been involved but the Empress began pushing for the law to be changed so that their daughter Theodora would ascend to the purple and managed to persuade her husband not to appoint Doux Symeon Caesar after Robin died. As both Adrianos and Eusebia were still under thirty it was hardly impossible they would have another son, but if they did not the succession might become problematic down the road...

The unsolved death of Prince Symeon.

[1] I don't know who did it myself. I suspect Doux Symeon but there are other would be claimants to the purple who haven't always been scrupulous.

guillec87: true, though it is good to have buffer states!

Specialist290: Well the death of my heir was a blow.

Henry v. Keiper: The Danube is very much my natural border in Europe. I'm still looking at other options though!

Chief Ragusa: Actually they are mostly the army I inherited along with my retinues. I also keep the Varangian Guard on permant retainer (they aren't onscreen there.)

GulMacet: That's far to go, but I'll think about it.

Nikolai: Two Patriarchs - Gabriel and Bardas.

Stuyvesant: The price of slaves dropping is historical truth after a big battle or capture of a city; it happened after the Battle of Hattin.

As for plans, well honestly I'm trying to decide. I'm a little reluctant to take the war to the Caliphate because in a narrative sense I want to see how the Muradids evolve. Of courase if they attack all bets are off!

Idhrendur: Thank you, I try to keep in character. I only blinded and castrated prisoners when the Cruel Emperor Symeon was in power.

The in game year is 968 AD meaning slightly over a century has passed in game. Here is a map of the Roman Empire in 968:

(Compare with the 866 AD map on the first page.)

Specialist290: Well the death of my heir was a blow.

Henry v. Keiper: The Danube is very much my natural border in Europe. I'm still looking at other options though!

Chief Ragusa: Actually they are mostly the army I inherited along with my retinues. I also keep the Varangian Guard on permant retainer (they aren't onscreen there.)

GulMacet: That's far to go, but I'll think about it.

Nikolai: Two Patriarchs - Gabriel and Bardas.

Stuyvesant: The price of slaves dropping is historical truth after a big battle or capture of a city; it happened after the Battle of Hattin.

As for plans, well honestly I'm trying to decide. I'm a little reluctant to take the war to the Caliphate because in a narrative sense I want to see how the Muradids evolve. Of courase if they attack all bets are off!

Idhrendur: Thank you, I try to keep in character. I only blinded and castrated prisoners when the Cruel Emperor Symeon was in power.

The in game year is 968 AD meaning slightly over a century has passed in game. Here is a map of the Roman Empire in 968:

(Compare with the 866 AD map on the first page.)

The Empire is strong and getting stronger. The Emperor... That's a tough loss. You can't replace a son, but I do hope the Empire gets a more secure succession than Adrianos's suspicious brother. But first, a continuance of Adrianos's prosperous reign! He's bringing the most internal peace the Empire has seen in a long time.

I do wonder how long the Caliphate will tolerate you nibbling away bits of his own sphere of influence friendly rivalry or not lol!

Great update though. All seems pretty stable for you at mo though I'm wondering his long that will last...

Quick question as I've tried looking it up: what is theme?

Great update though. All seems pretty stable for you at mo though I'm wondering his long that will last...

Quick question as I've tried looking it up: what is theme?

Since expaqnsion into the ME is out of the question for the moment, perhaps the Balkans should be united? Or Italy. But keep away from Rome, if you took it, the whole Catholic world would come down on you.

Quick question as I've tried looking it up: what is theme?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theme_(Byzantine_district)

But keep away from Rome, if you took it, the whole Catholic world would come down on you.

That, and there's really no good reason to want Rome in particular at this stage, at least historically speaking -- it's an empty shell of its former self, and the Great Schism technically hasn't even happened yet (despite the fact that the game models it otherwise. I can sort of understand why Paradox kind of glosses that over, but it's still a bit awkward to have "Catholic" and "Orthodox" as separate religions before the formal split.) A general reclamation of Italy (while perhaps giving the Pope a special exemption in due deference to his station) sounds like it might be in order, though, especially if there's no longer a Karling on the Italian throne to get his entire extended family mixed in with the conflict.

Killing off Symeon was a rather low blow for the game. Me and my big mouth... Glad as always to see the Empire expanding and integrating new territory, though.

Just when things go well, the lineage issue rears its ugly head again (but that's CK2 again).

Part Five - New Enemies, Old Enemies

The Saffarid dynasty of Persia was the most successful Muslim dynasty of the 9th and 10th century. The vast and wealthy Shahdom lacked the internal rot that had brought down the Abbasids and though faced with enemies in the unimaginably distant lands of India they lacked many of the foreign troubles that plagued Constantinople and Damascus alike. For a while they had enjoyed a vague alliance with the Abbasid Caliph, though the rise of the Muradids had rendered this moot.

The collapse of Armenia in the late 9th century had established a Saffarid toehold in the Kurdish territories of Amida and Nisibin, separated from Saffardid Empire by many miles of Abbasid (later Muradid) territory. For seventy years these territories had been left on their own under the lax rule of Persian governors but in the early 970s they began to attract more and more Roman attention. Having conquered Aleppo the Emperor Adrianos II sought to consolidate the rest of his Asian domains. Annexing the Saffarid domains would greatly strengthen his hand in eastern Asia Minor and project Roman authority beyond the far bank of the Tigris. Nisbin more however had a majority Christian population, albeit Miaphysite, left over from the days of Armenian rule. In May 971 the Romans invaded, easily brushing aside the locals garrisons though it would not be until June of the following year that the Shah would agree to a peace ceding the two territories. In triumph the Romans changed the name of the capital of Amida from the barbarously unpronounceable 'Kia Burc' to 'Adrianopolis of Mesopotamia'.

The following year saw the final act in the Bulgarian tragedy. On 5th January 973 the Romans invaded the tiny kingdom and by 24th February it was all over and the last province of the once might Bulgarian Empire belonged to Constantinople. King Drizislav trundled off into exile, his palace in Constantia occupied by a Roman governor. The Bulgarians had long since ceased to be a great threat to the Romans but memories of the menace they had been remained embedded in the public consciousness and news of the fall of Constantia resulted in celebrations the likes of which had not been seen since the capture of Antioch. There was a mass in Hagia Sophia - and a drunken public party in the Forum.

The war if such a short campaign can be called that was the last led by Captain Leon. The elderly Varangian general passed away not long after, too much sorrow. Leon was not a subtle general, or a sophisticated man; he had worn his Norse ways too obviously to be popular in Roman society, but he had been a loyal and gallant soldier and a great asset to the Empire. His funeral when it took place was worthy of a Caesar.

Adrianos was ruthless about expanding his empire, but to the people he conquered he was tolerant and gentle. Poor Drizislav fled from his besieged capital so quickly he left his wife behind. The Emperor sent her to him in safety with all her personal possessions intact and an honour guard befitting a queen. The Bulgarian churches who followed the Latin rite and looked to Rome were allowed to keep their positions, even the Bishop of Adamclisi who had been an intimate of the Bulgarian royals. While part of this was practical politics - the Bulgarians and the Kurds were his subjects - Adrianos genuinely believed in the light of Roman civilisation and the Orthodox Church. Famous for his charity Adrianos took a great interest in the poor, including those who had recently been his enemies. As much as it was noted for war the age of Adrianos was marked by the reappearance of cheap grain (from Siciliy) subsided by the Imperial purse.

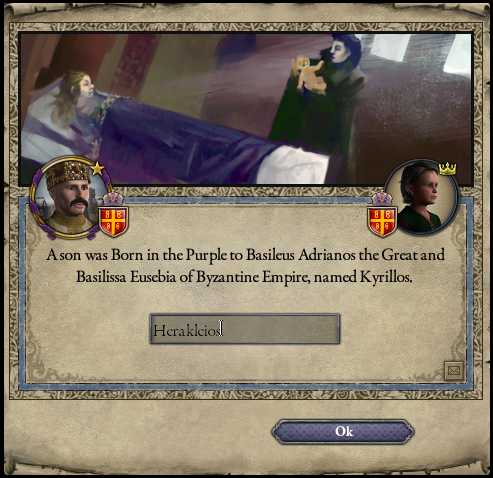

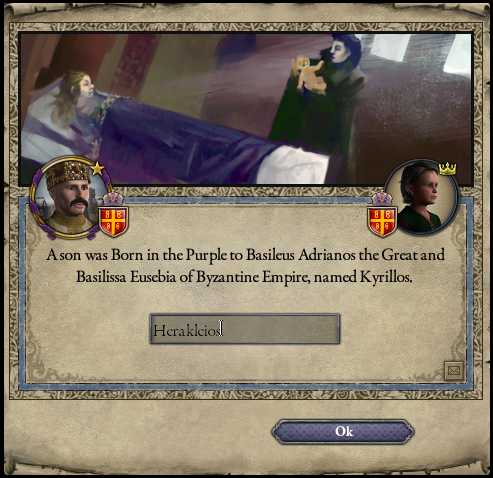

The birth of Herakleios.

The Roman citizenry would soon have another reason for celebration. On 23rd September 973 the Empress Eusebia gave birth to twins, itself noteworthy for Eusebia was thirty four and widely assumed to be passed her childbearing years. The elder of the twins was another daughter christened Nikoletta, followed three and half minutes later by her brother. Eusebia suggested naming the baby boy Kyrillos after his grandfather but Adrianos, though he had loved his father thought the name unfitting for a future Emperor. Instead he chose the name of one of his predecessors and heroes: Herakleios.

The birth of Herakleios pushed aside the delicate question of inheritance for now but it also brought a change in foreign policy. Previously the Emperor Adrianos had pursued an aggressive campaign of expansion against minor states on the pheriphary. The Empire had consolidated much territory and by 973 was sufficiently strong that a war against the Caliphate itself could be countenanced. However no one knew better than Adrianos the risks of an Emperor dying too young and leaving a child to inherit. A war against Tripoli would be a tremendous undertaking that would certainly require the Emperor to spend years away on campaign with all the risks involved. So for the time being the prospect of foreign wars faded.

For Adrianos the peace allowed time to continue his public building programme and reform the army. Previously the Kataphraktoi retinues had been the core of the standing army but Adrianos, though greatly appreciating their power considered them expensive and inflexible, especially in rough terrain that was the battleground the Romans frequently fought in. Of the seven standing Kataphraktoi brigades five were disbanded, replaced by faster light cavalry brigades, augmented by brigades of shock infantry and skirmishers. He could not know when war might strike but when it did so he intended the army would not be found wanting.

The Roman Empire in 974 AD.

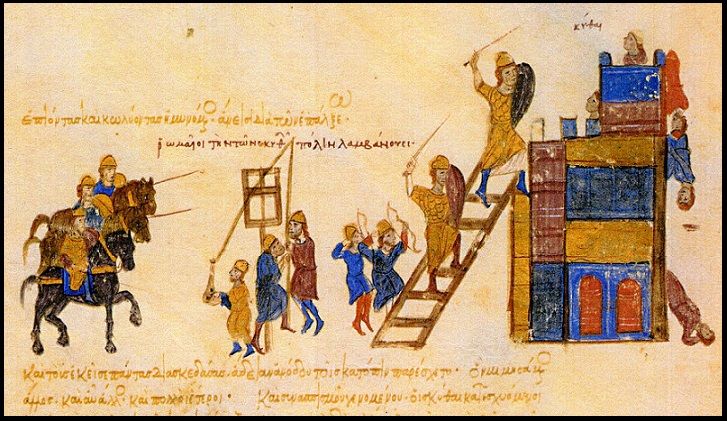

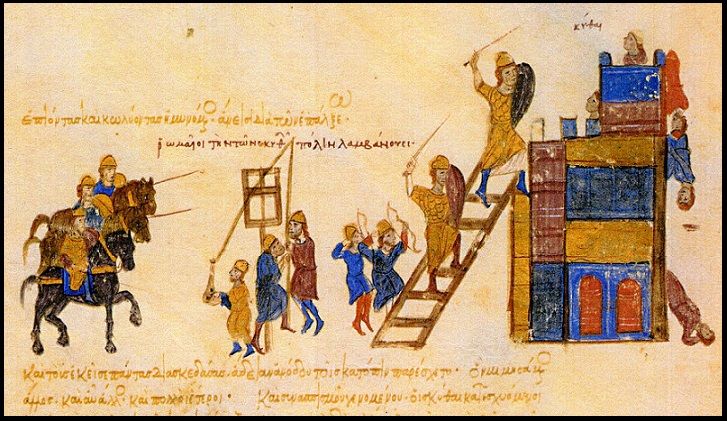

The Roman capture of Constantia, 973 AD.

The Saffarid dynasty of Persia was the most successful Muslim dynasty of the 9th and 10th century. The vast and wealthy Shahdom lacked the internal rot that had brought down the Abbasids and though faced with enemies in the unimaginably distant lands of India they lacked many of the foreign troubles that plagued Constantinople and Damascus alike. For a while they had enjoyed a vague alliance with the Abbasid Caliph, though the rise of the Muradids had rendered this moot.

The collapse of Armenia in the late 9th century had established a Saffarid toehold in the Kurdish territories of Amida and Nisibin, separated from Saffardid Empire by many miles of Abbasid (later Muradid) territory. For seventy years these territories had been left on their own under the lax rule of Persian governors but in the early 970s they began to attract more and more Roman attention. Having conquered Aleppo the Emperor Adrianos II sought to consolidate the rest of his Asian domains. Annexing the Saffarid domains would greatly strengthen his hand in eastern Asia Minor and project Roman authority beyond the far bank of the Tigris. Nisbin more however had a majority Christian population, albeit Miaphysite, left over from the days of Armenian rule. In May 971 the Romans invaded, easily brushing aside the locals garrisons though it would not be until June of the following year that the Shah would agree to a peace ceding the two territories. In triumph the Romans changed the name of the capital of Amida from the barbarously unpronounceable 'Kia Burc' to 'Adrianopolis of Mesopotamia'.

The following year saw the final act in the Bulgarian tragedy. On 5th January 973 the Romans invaded the tiny kingdom and by 24th February it was all over and the last province of the once might Bulgarian Empire belonged to Constantinople. King Drizislav trundled off into exile, his palace in Constantia occupied by a Roman governor. The Bulgarians had long since ceased to be a great threat to the Romans but memories of the menace they had been remained embedded in the public consciousness and news of the fall of Constantia resulted in celebrations the likes of which had not been seen since the capture of Antioch. There was a mass in Hagia Sophia - and a drunken public party in the Forum.

The war if such a short campaign can be called that was the last led by Captain Leon. The elderly Varangian general passed away not long after, too much sorrow. Leon was not a subtle general, or a sophisticated man; he had worn his Norse ways too obviously to be popular in Roman society, but he had been a loyal and gallant soldier and a great asset to the Empire. His funeral when it took place was worthy of a Caesar.

Adrianos was ruthless about expanding his empire, but to the people he conquered he was tolerant and gentle. Poor Drizislav fled from his besieged capital so quickly he left his wife behind. The Emperor sent her to him in safety with all her personal possessions intact and an honour guard befitting a queen. The Bulgarian churches who followed the Latin rite and looked to Rome were allowed to keep their positions, even the Bishop of Adamclisi who had been an intimate of the Bulgarian royals. While part of this was practical politics - the Bulgarians and the Kurds were his subjects - Adrianos genuinely believed in the light of Roman civilisation and the Orthodox Church. Famous for his charity Adrianos took a great interest in the poor, including those who had recently been his enemies. As much as it was noted for war the age of Adrianos was marked by the reappearance of cheap grain (from Siciliy) subsided by the Imperial purse.

The birth of Herakleios.

The Roman citizenry would soon have another reason for celebration. On 23rd September 973 the Empress Eusebia gave birth to twins, itself noteworthy for Eusebia was thirty four and widely assumed to be passed her childbearing years. The elder of the twins was another daughter christened Nikoletta, followed three and half minutes later by her brother. Eusebia suggested naming the baby boy Kyrillos after his grandfather but Adrianos, though he had loved his father thought the name unfitting for a future Emperor. Instead he chose the name of one of his predecessors and heroes: Herakleios.

The birth of Herakleios pushed aside the delicate question of inheritance for now but it also brought a change in foreign policy. Previously the Emperor Adrianos had pursued an aggressive campaign of expansion against minor states on the pheriphary. The Empire had consolidated much territory and by 973 was sufficiently strong that a war against the Caliphate itself could be countenanced. However no one knew better than Adrianos the risks of an Emperor dying too young and leaving a child to inherit. A war against Tripoli would be a tremendous undertaking that would certainly require the Emperor to spend years away on campaign with all the risks involved. So for the time being the prospect of foreign wars faded.

For Adrianos the peace allowed time to continue his public building programme and reform the army. Previously the Kataphraktoi retinues had been the core of the standing army but Adrianos, though greatly appreciating their power considered them expensive and inflexible, especially in rough terrain that was the battleground the Romans frequently fought in. Of the seven standing Kataphraktoi brigades five were disbanded, replaced by faster light cavalry brigades, augmented by brigades of shock infantry and skirmishers. He could not know when war might strike but when it did so he intended the army would not be found wanting.

The Roman Empire in 974 AD.