The infidels are splintering. Excellent, use that to your advantage and recover Syria... or perhaps Armenia...

The Queen of Cities: A Byzantine AAR

- Thread starter RossN

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Rome needs to strike down hard and capture as much land as possible before the Caliphate regroups!

time to grab some easy land? there is a lot of independent counties now in the Middle East

It's always by satisfying to watch an enemy power crumble from within. I have been observing the trials of England in my game from Scotland, Ireland and Wales with similar glee hehehe

Especially when they're large and powerful like a lot of the Muslim states are at the beginning of CK2.

I like that perspective change a lot. It's good to see the Abbasid demise up front and personal, and it sounds like the regency was fairly uneventful - good for you, but less interesting from a narrative perspective. So yes, good choice, as far as I'm concerned.

I'm looking forward to finding out what kind of Emperor Adrianos will make. Here's hoping that the turmoil in the Middle East gives the Empire opportunities to expand, instead of merely signalling the change from one powerful Muslim foe to another.

I'm looking forward to finding out what kind of Emperor Adrianos will make. Here's hoping that the turmoil in the Middle East gives the Empire opportunities to expand, instead of merely signalling the change from one powerful Muslim foe to another.

Certainly an intriguing perspective flip. It's good to peek behind the curtain once in a while and see what's going on on the other side of Byzantium's borders.

Also glad to hear that Adrianos's reign has been mostly uneventful, though I imagine this is going to change rather quickly once he reaches adulthood.

Also glad to hear that Adrianos's reign has been mostly uneventful, though I imagine this is going to change rather quickly once he reaches adulthood.

The standard setting is to subscribe when you post in a thread. Then you can find it in your settings page in the upper right corner of the forums, when there is new posts.

Then you can find it in your settings page in the upper right corner of the forums, when there is new posts.

Alternately, you can also subscribe through the Thread Tools dropdown in the upper right corner of the thread.

Part Two - Antioch

The Emperor Adrianos II had already worn the purple for more than half his life when he finally reached adulthood and began to rule in his own right in 957. He was a clever, pleasant young man, skilled at public speaking and politics, though his interests were primarily military. Though not intellectual by nature he was aware of the history of his family and country and knew he had much to live up. The aging Robin of Amalfi remained at court as Strategos (and now also rewarded with the title of Caesar) as did his father's venerable Sakelaris Count Laurentios of Euboea and the Ecumenical Patriarch Photios II[1]. The combination of a personally popular young Emperor and highly experienced court gave the Roman political world more stability than it had known since the days of Leon VI.

Following the tradition of his father Adrianos married a Roman woman rather than a foreign princess. Eusebia of Blachernae was of similar age to her husband and shared many of his traits, though she was perhaps more slightly intelligent overall. The match proved a happy one and their daughter Theodora was September 959. The young Emperor possessed the personal eccentricity of faithfulness, leading to a harmonious and loving marriage but a lot of bemusement amongst the gossipmongers of Constantinople.

The astonishing collapse of the Abbasids had sent ripples across the Near East. With the Muradin Caliphate itself relations were actually rather good; Adrianos was fully willing to seek the friendship of Murad who had no historic grudge against the Romans and might provide a useful buffer against the Kingdom of Georgia which was again growing in power. The sudden death of Murad in battle in October 957, followed mere weeks later by the mysterious death of his son Caliph Muslihiddin[2] left the Muradin Caliphate in the hands of five year old Caliph Faruk. Alarmed Adrianos sent another embassy to Dwin to seek alliance or at least benign neutrality with the grand vizier.

Against the smaller states who had declared independence from the Caliph the Romans were far more ambitious. The areas around Antioch were in the hands of Walid the Cruel, an Egyptian based Emir who was leading a revolt against the Muradins. Antioch itself paid tribute to Abu’l III Husayn, the Mustazhirid Emir of Tortosa who also claimed (but did not control) Edessa and Tripoli. Neither was likely to put up much resistance so Adrianos declared war on both in May 957.

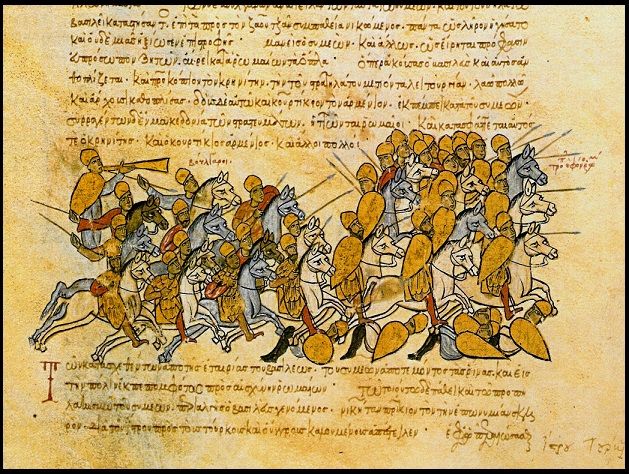

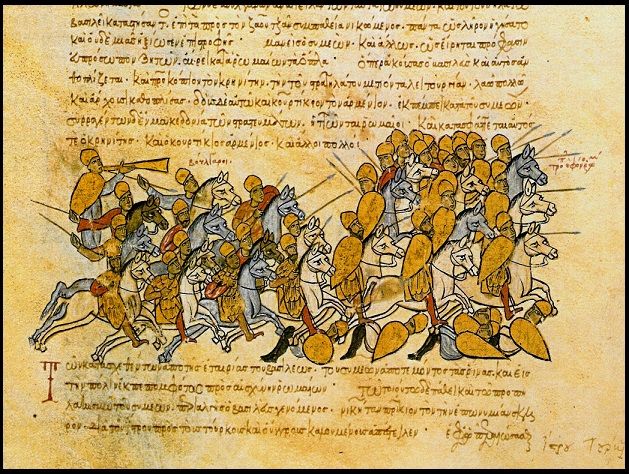

Much of the Roman army had to be kept in Europe to face the threat of the adventurer Domoszló and his designs on Rascia[3] but that still left the Varangian Guard, the Kataphraktoi regiments and levies from the themes of Asia Minor. Despite the intervention of the Emir of Aleppo (who earned the lasting enmity of the Romans) the war ran smoothly, mostly a series of sieges interspersed with sharp but short battles. Tortosa fell in February 958, Marclea followed in June and soon after the titular Emir of Tripoli sued for peace. Walid’s territory proved a trickier proposition and the Romans had to defeat a relief army from Egypt before he surrendered his Syrian territory in January 959. Only Antioch itself remained in Muslim hands, belonging to a Wali who had outlasted his temporal lord the Emir of Tortosa. As soon as Walid sued for peace the Romans began to lay siege to the ancient city and were fully prepared to storm it when sympathisers in the city opened the gates – much to the relief the Romans who dreaded the prospect of taking so holy a city by storm.

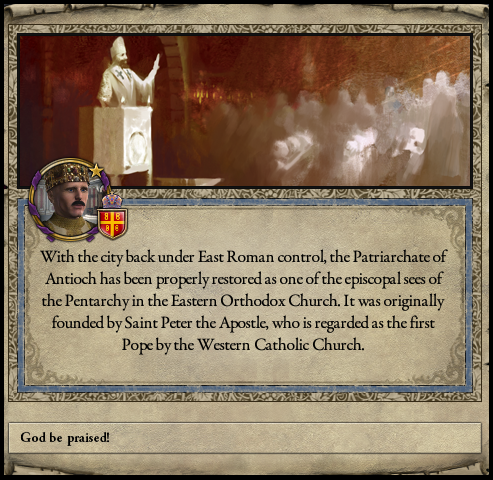

The young Patriarch of Antioch.

Antioch was Roman again and on 24th February 959 the first Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch in decades was consecrated. Bardas Straiotkos, a Sicilian Greek by birth who had been an army chaplain was elected Patriarch. He was a fine choice, pious man known for sense of justice and charitable nature but no stranger to diplomacy. He’d need that last as the Emperor Adrianos II (who went as a pilgrim to Antioch not long after) invested the Patriarchate with a great deal of power and land[4]. His reasons for doing so were complicated.

Antioch was of tremendous religious importance to all major branches of Eastern Christendom. By raising the Patriarch to be a powerful temporal figure in his own right the Emperor made a very strong claim that the Orthodox Church was the rightful power in Antioch. The rival Syrian Orthodox Church would hopefully rapidly diminish in the face of the wealth and prestige of Patriarch Bardas and his successors. Another reason had more to do with the internal politics of the Church in the Empire. While Adrianos had very good relations with the current Ecumenical Patriarch he knew Emperors had often clashed with their leading churchmen – his own grandfather had blinded one of Photios’ predecessors! A strong Patriarch of Antioch would provide a counterweight to an overambitious Ecumenical Patriarch. The Antiochenes might acknowledge the primacy of Constantinople but they knew their own lineage was much older, stretching back to the Apostles themselves.

Finally of course the restoration of Antioch restored one of the great centres of pilgrimage. Every Emperor since Basileios had paid a visit to the city as a pilgrim and the Makedon line had strong feelings of protectiveness and devotion towards the palace. The thought of placing it under some crude tax collector or military governor revolted the Imperial sensibilities. Antioch was not just an ordinary city and should not be treated as such. If he had any doubts the Emperor's pilgrimage removed them as the monks cured him of an illness that had dogged him for some weeks. If only Antioch had been Roman in Kyrillos' day!

[1] All three of these men are survivors from the time of Kyrillos's minority amazingly. Robin in particular has continuously been Strategos for almost thirty years by this point (even following Kyrillos into exile during the brief reign of Porphyrios.)

[2] I had nothing to do with either death but Muslihiddin did die under 'suspicious circumstances'. It is possible the Abbasids did it but the Muradins have many enemies.

[3] Another adventurer! This one was Hungarian and luckily I was able to defeat him without too much trouble; the terrain was very much in my favour.

[4] I gave the Bishop of Antioch (ie. The Patriarch) the Duchy of Antioch.

The Emperor Adrianos II in late 959 AD.

The Emperor Adrianos II had already worn the purple for more than half his life when he finally reached adulthood and began to rule in his own right in 957. He was a clever, pleasant young man, skilled at public speaking and politics, though his interests were primarily military. Though not intellectual by nature he was aware of the history of his family and country and knew he had much to live up. The aging Robin of Amalfi remained at court as Strategos (and now also rewarded with the title of Caesar) as did his father's venerable Sakelaris Count Laurentios of Euboea and the Ecumenical Patriarch Photios II[1]. The combination of a personally popular young Emperor and highly experienced court gave the Roman political world more stability than it had known since the days of Leon VI.

Following the tradition of his father Adrianos married a Roman woman rather than a foreign princess. Eusebia of Blachernae was of similar age to her husband and shared many of his traits, though she was perhaps more slightly intelligent overall. The match proved a happy one and their daughter Theodora was September 959. The young Emperor possessed the personal eccentricity of faithfulness, leading to a harmonious and loving marriage but a lot of bemusement amongst the gossipmongers of Constantinople.

The astonishing collapse of the Abbasids had sent ripples across the Near East. With the Muradin Caliphate itself relations were actually rather good; Adrianos was fully willing to seek the friendship of Murad who had no historic grudge against the Romans and might provide a useful buffer against the Kingdom of Georgia which was again growing in power. The sudden death of Murad in battle in October 957, followed mere weeks later by the mysterious death of his son Caliph Muslihiddin[2] left the Muradin Caliphate in the hands of five year old Caliph Faruk. Alarmed Adrianos sent another embassy to Dwin to seek alliance or at least benign neutrality with the grand vizier.

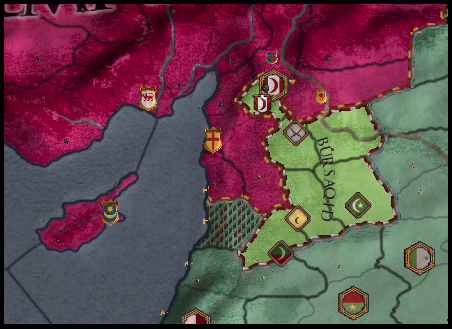

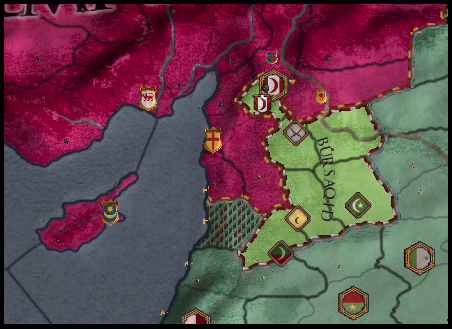

Against the smaller states who had declared independence from the Caliph the Romans were far more ambitious. The areas around Antioch were in the hands of Walid the Cruel, an Egyptian based Emir who was leading a revolt against the Muradins. Antioch itself paid tribute to Abu’l III Husayn, the Mustazhirid Emir of Tortosa who also claimed (but did not control) Edessa and Tripoli. Neither was likely to put up much resistance so Adrianos declared war on both in May 957.

Much of the Roman army had to be kept in Europe to face the threat of the adventurer Domoszló and his designs on Rascia[3] but that still left the Varangian Guard, the Kataphraktoi regiments and levies from the themes of Asia Minor. Despite the intervention of the Emir of Aleppo (who earned the lasting enmity of the Romans) the war ran smoothly, mostly a series of sieges interspersed with sharp but short battles. Tortosa fell in February 958, Marclea followed in June and soon after the titular Emir of Tripoli sued for peace. Walid’s territory proved a trickier proposition and the Romans had to defeat a relief army from Egypt before he surrendered his Syrian territory in January 959. Only Antioch itself remained in Muslim hands, belonging to a Wali who had outlasted his temporal lord the Emir of Tortosa. As soon as Walid sued for peace the Romans began to lay siege to the ancient city and were fully prepared to storm it when sympathisers in the city opened the gates – much to the relief the Romans who dreaded the prospect of taking so holy a city by storm.

The young Patriarch of Antioch.

Antioch was Roman again and on 24th February 959 the first Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch in decades was consecrated. Bardas Straiotkos, a Sicilian Greek by birth who had been an army chaplain was elected Patriarch. He was a fine choice, pious man known for sense of justice and charitable nature but no stranger to diplomacy. He’d need that last as the Emperor Adrianos II (who went as a pilgrim to Antioch not long after) invested the Patriarchate with a great deal of power and land[4]. His reasons for doing so were complicated.

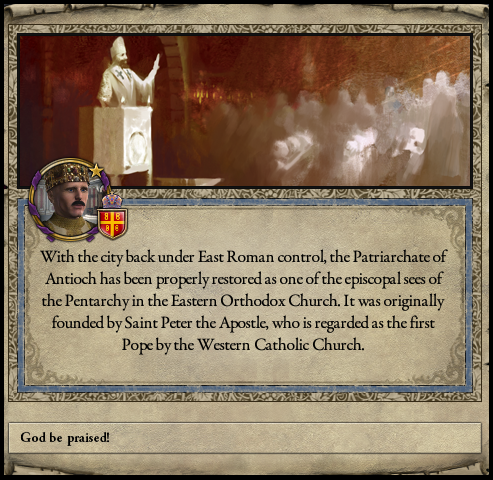

Antioch was of tremendous religious importance to all major branches of Eastern Christendom. By raising the Patriarch to be a powerful temporal figure in his own right the Emperor made a very strong claim that the Orthodox Church was the rightful power in Antioch. The rival Syrian Orthodox Church would hopefully rapidly diminish in the face of the wealth and prestige of Patriarch Bardas and his successors. Another reason had more to do with the internal politics of the Church in the Empire. While Adrianos had very good relations with the current Ecumenical Patriarch he knew Emperors had often clashed with their leading churchmen – his own grandfather had blinded one of Photios’ predecessors! A strong Patriarch of Antioch would provide a counterweight to an overambitious Ecumenical Patriarch. The Antiochenes might acknowledge the primacy of Constantinople but they knew their own lineage was much older, stretching back to the Apostles themselves.

The religious importance of Antioch.

Finally of course the restoration of Antioch restored one of the great centres of pilgrimage. Every Emperor since Basileios had paid a visit to the city as a pilgrim and the Makedon line had strong feelings of protectiveness and devotion towards the palace. The thought of placing it under some crude tax collector or military governor revolted the Imperial sensibilities. Antioch was not just an ordinary city and should not be treated as such. If he had any doubts the Emperor's pilgrimage removed them as the monks cured him of an illness that had dogged him for some weeks. If only Antioch had been Roman in Kyrillos' day!

Antioch, Tortosa & the Emirate of Aleppo, 960 AD.

[1] All three of these men are survivors from the time of Kyrillos's minority amazingly. Robin in particular has continuously been Strategos for almost thirty years by this point (even following Kyrillos into exile during the brief reign of Porphyrios.)

[2] I had nothing to do with either death but Muslihiddin did die under 'suspicious circumstances'. It is possible the Abbasids did it but the Muradins have many enemies.

[3] Another adventurer! This one was Hungarian and luckily I was able to defeat him without too much trouble; the terrain was very much in my favour.

[4] I gave the Bishop of Antioch (ie. The Patriarch) the Duchy of Antioch.

Asantahene: Yes, yes it is right?

GulMacet, Nikolai and guillec87: Easy land grabbed.

Henry v. Keiper: Very true. currently the most powerful Muslim state are the Ummayads in Spain who seem pretty stable (though the Saffarids in Persia are also doing well.)

Stuyvesant and Specialist290: Glad you both like the flip. I thought it was an important enough development I had to take a closer look.

From a narrative point of view I acually hope the Muradid's stabilise. Aside from the game being more interesting with a 'rival' like this it's fascinating to see such a different Caliphate rise!

Dakilla TM: Welcome, really glad you like it! For subscribing just follow the advice Nikolai and Specialist290 gave you.

For subscribing just follow the advice Nikolai and Specialist290 gave you.

GulMacet, Nikolai and guillec87: Easy land grabbed.

Henry v. Keiper: Very true. currently the most powerful Muslim state are the Ummayads in Spain who seem pretty stable (though the Saffarids in Persia are also doing well.)

Stuyvesant and Specialist290: Glad you both like the flip. I thought it was an important enough development I had to take a closer look.

From a narrative point of view I acually hope the Muradid's stabilise. Aside from the game being more interesting with a 'rival' like this it's fascinating to see such a different Caliphate rise!

Dakilla TM: Welcome, really glad you like it!

And they were first called Christians at Antioch, Acts 11:26. Eh, I suppose it's time to retake Jerusalem, Nazareth, and Origen's hometown of Alexandria next...

Alexios is certainly off to a flying start! Antioch and its surroundings recaptured within one (or two) years of reaching majority - quite the feat. How is support for the young Emperor amongst the nobility of the Empire? And has the succession been secured yet? If the internal situation is calm (and if he can actually stay alive for a good time), then this could be an age of expansion.

Looks like RossN's maxed out his bandwidth limit for the time being, as they were there when I first opened this thread.

Nice to see Antioch once again in Christian hands, considering its place in that religion's heritage (which volksmarschall has so graciously reminded us of). The situation in the East may indeed be ripe for a Roman resurgence, although I'm also rather curious how the western frontier is holding up (though that adventurer invasion does seem to suggest tantalizing hints of disorder beyond your borders).

Nice to see Antioch once again in Christian hands, considering its place in that religion's heritage (which volksmarschall has so graciously reminded us of). The situation in the East may indeed be ripe for a Roman resurgence, although I'm also rather curious how the western frontier is holding up (though that adventurer invasion does seem to suggest tantalizing hints of disorder beyond your borders).

Sorry about that the bandwith issue should be fixed now.

Currently the succession would go to Adrianos' younger (but still adult) brother Symeon, Doux of Adrianople. He would not make a great Emperor going by his traits but he is no would be Caligula or Nero either. Adrianos himself is very popular: being kind, gregarious, charitable and temperate tends to impress people and he now has a lot of prestige working for him.

The Empire's western frontier is stable in Italy and mostly so along the Danube but I'll be going into than in the next update!

Currently the succession would go to Adrianos' younger (but still adult) brother Symeon, Doux of Adrianople. He would not make a great Emperor going by his traits but he is no would be Caligula or Nero either. Adrianos himself is very popular: being kind, gregarious, charitable and temperate tends to impress people and he now has a lot of prestige working for him.

The Empire's western frontier is stable in Italy and mostly so along the Danube but I'll be going into than in the next update!

Last edited:

Part Three – On the Danube

The years immediately after the capture of Antioch were a Golden Age for the Roman Empire, reminiscent of the time of Leon VI half a century earlier. Adrianos was popular and respected, so much so that the Senate voted he be called Adrianos ho Mégas ('Adrianos the Great'). The birth of his son Symeon in November 963 seemed to guarantee the succession. The treasury was full, the borders more secure than in generations and trade flourished with the West. A growing population led to the establishment of a new city founded near Tortosa. The colony, settled from the seemingly endless pool of Constantinople poor was named Adrianosopolis after the Emperor (called Adrianopolis in Syria to distinguish it from the great city in Thrace[1].) The stability of the Empire saw a rise in Frankish and Italian pilgrims en-route to Antioch, who returned home spreading word of the wealth and power of the Romans.

That power rested on military strength. The Roman Army of the 10th century was a powerful force; a standing army of about eighteen thousand formed around a core of heavy cavalry and Varangian guardsmen. Together with the levies raised from the themes Adrianos could raise a field army with a grand total of perhaps fifty five thousand soldiers, though in truth no Emperor would dare do so unless faced with a threat to the very existence of the Empire. The Makedons preferred to field armies of ten to twelve thousand which were more flexible while being large enough to besiege and take cities. Above all it did not place the future of the Empire in one basket because however capable, disciplined and well led the Romans were not invincible. Back in 948 during the war with the Abbasids the Romans had suffered a catastrophic defeat at Hireapolis where an entire army of nine and a half thousand was killed or captured; according to Arab chroniclers the price of male slaves fell to unheard of lows in Damascus in the days after the battle. The Romans had sufficient reserves to recover, and defeat the Abbasids but it was a lesson they did not forget in a hurry.

The great Roman fear was to fight two great enemies at once. This had happened in the very recent past when the adventurer Domoszló had invaded while the Romans had been fighting the Arabs. Domoszló, a Hungarian with an obscure claim on Rascia had assembled a vast army of malcontents and mercenaries but lacked the skill to lead them properly and his men had perished in droves before the Romans on the banks of the Danube. However the next adventurer might be a greater threat.

After the end of the Antiochene War the Emperor had turned his focus to the Danube. The great river formed the natural border for the Empire and for the past century the Romans had been slowly pushing north at the expense of Bulgaria. By 962 the tiny kingdom was clinging to the Euxine Sea and a swift campaign by the Romans that began in April of that year reduced it still further as Karvuna was annexed. The wretched King Drizislav was permitted to maintain a precarious independence for the moment. Relations with Hungary were far friendlier (Domoszló aside). For decades the Hungarian royals had been linked with the Imperial Family and King Ödön was married to Adrianos's sister. To the west (on the Imperial side of the Danube) lay the independent states of Slavonia and Croatia, home to many of the brigands who aided Domoszló and therefore an object of deep Roman suspicion. In January 965 Adrianos went to war with the two duchies, determined to finally secure the Empire's Danubian frontier before returning his attentions back to Asia.

The campaign was a swift one, fought using the troops from the Balkan themes and the Varangian Guard. Adrianos was genuinely hoping to establish good relations with the Muradin Caliphate but he was more than savvy enough to keep the bulk of the army ready incase the Arabs went to war. The Emperor did see some combat, and led well but the Roman armies were chiefly led by Caption Leon, a Varangian veteran officer who had converted to Christianity. By December 965 Leon and the other generals had conquered Krizevci and Usora, pushing the roman frontier into the northwest and securing almost total control of the southern banks of the Danube. The diminished Slavonia and Croatia were now too small to be a serious threat and had in fact become useful buffer states against the Franks.

During the war the elderly Ecumenical Patriarch Photinos II died. Relations between the Emperor and Photinos had been warm but the old Patriarch had always maintained a certain aloofness. His successor was a young priest from Sinope, known for his kindliness, temperance and deep theological insight (and less appreciated for his streak of envy). Patriarch Gabriel at once got along well with the Emperor. By a strange turn of fortune, or perhaps providence both the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople and the Patriarch of Antioch were young men, as was the Emperor, himself a zealous man known for his support of the church. Eastern Christendom was slowly recovering from the Iconoclast heresy and Gabriel and Bardas were part of a new wave of clever, devout young men who dominated the Orthodox Church. If they had a flaw it was their tendency towards intolerance towards the Armenian Miaphysites, though as yet they were too few for this to be problematic outside of Edessa where they made up a majority of the populace and had an uneasy relationship with the official Church.

The Catholics who looked to the Bishop of Rome as their spiritual leader were more numerous but surprisingly less troublesome, lacking the long tradition of conflict with Orthodoxy that distingushed the Miaphysites and other eastern churches. They tended to assimilate swiftly[2].

Ecumenical Patriarch Gabriel in 965 AD.

[1] Adrianopolis in Syria is a City built in Tortosa county. I renamed it from Margat but I think Jabala makes more sense for a city as against a castle, so assume it is built on that site.

[2] My religious policy is to try and convert Muslims and heretical offshoots of Orthodoxy (like Iconoclasm) and leave everyone alone. The exception is when I have an Emperor with Sympathy for Islam, like Leon VI. When that happens I stick to converting heretics.

Romans vs. Slavonians, 965 AD.

The years immediately after the capture of Antioch were a Golden Age for the Roman Empire, reminiscent of the time of Leon VI half a century earlier. Adrianos was popular and respected, so much so that the Senate voted he be called Adrianos ho Mégas ('Adrianos the Great'). The birth of his son Symeon in November 963 seemed to guarantee the succession. The treasury was full, the borders more secure than in generations and trade flourished with the West. A growing population led to the establishment of a new city founded near Tortosa. The colony, settled from the seemingly endless pool of Constantinople poor was named Adrianosopolis after the Emperor (called Adrianopolis in Syria to distinguish it from the great city in Thrace[1].) The stability of the Empire saw a rise in Frankish and Italian pilgrims en-route to Antioch, who returned home spreading word of the wealth and power of the Romans.

That power rested on military strength. The Roman Army of the 10th century was a powerful force; a standing army of about eighteen thousand formed around a core of heavy cavalry and Varangian guardsmen. Together with the levies raised from the themes Adrianos could raise a field army with a grand total of perhaps fifty five thousand soldiers, though in truth no Emperor would dare do so unless faced with a threat to the very existence of the Empire. The Makedons preferred to field armies of ten to twelve thousand which were more flexible while being large enough to besiege and take cities. Above all it did not place the future of the Empire in one basket because however capable, disciplined and well led the Romans were not invincible. Back in 948 during the war with the Abbasids the Romans had suffered a catastrophic defeat at Hireapolis where an entire army of nine and a half thousand was killed or captured; according to Arab chroniclers the price of male slaves fell to unheard of lows in Damascus in the days after the battle. The Romans had sufficient reserves to recover, and defeat the Abbasids but it was a lesson they did not forget in a hurry.

The great Roman fear was to fight two great enemies at once. This had happened in the very recent past when the adventurer Domoszló had invaded while the Romans had been fighting the Arabs. Domoszló, a Hungarian with an obscure claim on Rascia had assembled a vast army of malcontents and mercenaries but lacked the skill to lead them properly and his men had perished in droves before the Romans on the banks of the Danube. However the next adventurer might be a greater threat.

After the end of the Antiochene War the Emperor had turned his focus to the Danube. The great river formed the natural border for the Empire and for the past century the Romans had been slowly pushing north at the expense of Bulgaria. By 962 the tiny kingdom was clinging to the Euxine Sea and a swift campaign by the Romans that began in April of that year reduced it still further as Karvuna was annexed. The wretched King Drizislav was permitted to maintain a precarious independence for the moment. Relations with Hungary were far friendlier (Domoszló aside). For decades the Hungarian royals had been linked with the Imperial Family and King Ödön was married to Adrianos's sister. To the west (on the Imperial side of the Danube) lay the independent states of Slavonia and Croatia, home to many of the brigands who aided Domoszló and therefore an object of deep Roman suspicion. In January 965 Adrianos went to war with the two duchies, determined to finally secure the Empire's Danubian frontier before returning his attentions back to Asia.

The campaign was a swift one, fought using the troops from the Balkan themes and the Varangian Guard. Adrianos was genuinely hoping to establish good relations with the Muradin Caliphate but he was more than savvy enough to keep the bulk of the army ready incase the Arabs went to war. The Emperor did see some combat, and led well but the Roman armies were chiefly led by Caption Leon, a Varangian veteran officer who had converted to Christianity. By December 965 Leon and the other generals had conquered Krizevci and Usora, pushing the roman frontier into the northwest and securing almost total control of the southern banks of the Danube. The diminished Slavonia and Croatia were now too small to be a serious threat and had in fact become useful buffer states against the Franks.

The Danubian border in 966 AD.

During the war the elderly Ecumenical Patriarch Photinos II died. Relations between the Emperor and Photinos had been warm but the old Patriarch had always maintained a certain aloofness. His successor was a young priest from Sinope, known for his kindliness, temperance and deep theological insight (and less appreciated for his streak of envy). Patriarch Gabriel at once got along well with the Emperor. By a strange turn of fortune, or perhaps providence both the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople and the Patriarch of Antioch were young men, as was the Emperor, himself a zealous man known for his support of the church. Eastern Christendom was slowly recovering from the Iconoclast heresy and Gabriel and Bardas were part of a new wave of clever, devout young men who dominated the Orthodox Church. If they had a flaw it was their tendency towards intolerance towards the Armenian Miaphysites, though as yet they were too few for this to be problematic outside of Edessa where they made up a majority of the populace and had an uneasy relationship with the official Church.

The Catholics who looked to the Bishop of Rome as their spiritual leader were more numerous but surprisingly less troublesome, lacking the long tradition of conflict with Orthodoxy that distingushed the Miaphysites and other eastern churches. They tended to assimilate swiftly[2].

Ecumenical Patriarch Gabriel in 965 AD.

[1] Adrianopolis in Syria is a City built in Tortosa county. I renamed it from Margat but I think Jabala makes more sense for a city as against a castle, so assume it is built on that site.

[2] My religious policy is to try and convert Muslims and heretical offshoots of Orthodoxy (like Iconoclasm) and leave everyone alone. The exception is when I have an Emperor with Sympathy for Islam, like Leon VI. When that happens I stick to converting heretics.

volksmarschall: Perhaps not quite yet but maybe in time.

Stuyvesant: The succession is secure for the moment with the birth of Prince Symeon. Unfortunately he is a sickly child.

Henry v. Keiper: Indeed.

guillec87: Pics restored!

Specialist290: I tried to detail events on the Empire's European border here. In general the story has been one of slow but relentless advance to the natural (and historic) border of the Danube.

Asantahene: There you go.

Stuyvesant: The succession is secure for the moment with the birth of Prince Symeon. Unfortunately he is a sickly child.

Henry v. Keiper: Indeed.

guillec87: Pics restored!

Specialist290: I tried to detail events on the Empire's European border here. In general the story has been one of slow but relentless advance to the natural (and historic) border of the Danube.

Asantahene: There you go.