Kalina and I spent most of the next Friday skipping class to hang out together at the Kapitolion, which was only a few blocks away from the archaeology department. The Kapitolion was one of the oldest standing buildings in the city, and it housed the museum showcasing the history of the Imperial governments. And although we had seen the length and breath of the collection in under two hours, the Kapitolion Square also harboured some of the most interested café’s and novelty shops outside the Byzantion ward. Kalina left after our early dinner, to catch her train to Philippopolis and meet up with her parents. As her parents were divorced, and she wasn’t very fond of her mother, she would stay with her father. According to her stories, he was a really swell guy, but when I offered to go with her to meet him, she said he probably get a heart attack when he heard his little girl had a boyfriend. Maybe she was right, and it was just too early. So that Friday evening I waved her goodbye on platform 6, and as always hoped to see her back again in one piece Tuesday.

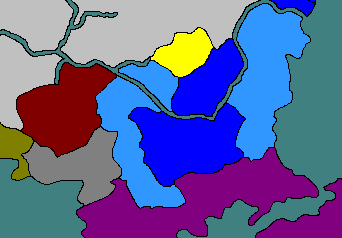

In other words, the weekend was rather slow, and instead of doing all the due homework I should have been doing I spent most time hanging on the couch or taking small strolls along the old wall. That Tuesday, the online schedule announced mister Doxiadus would once again not be able to make to the workshop. As I didn’t have any time for my assignment for that class, I didn’t really mind. When I saw Kalina before the lecture hall that afternoon, she told me she had gone so tired of her mother’s theatrics that she would invite her father to Constantinople from now on, and that Philippopolis could burn to the ground as far as she was concerned. We went into the lecture hall, where the professor was apparently ready to start. In fact, he closed the door less than a minute later, and he began his lecture with showing a coloured map on the screen. The different shapes and colours indicated it was indeed a map, but not one that seemed very familiar. It certainly wasn’t the Levant.

“Welcome everybody. I hope your weekend was as fun as mine. I’ve been to Korinthos this weekend, together with Professor Sisinis to visit a new dig one of our friends is leading. He believes to be able find a lot of new and exciting stuff about the city. Everybody who also follows my lectures at the archaeology department; prepare for a treat!”

I heard Kalina say ‘I wonder where he’d been off to,’ and I could see a spark of excitement in her eyes.

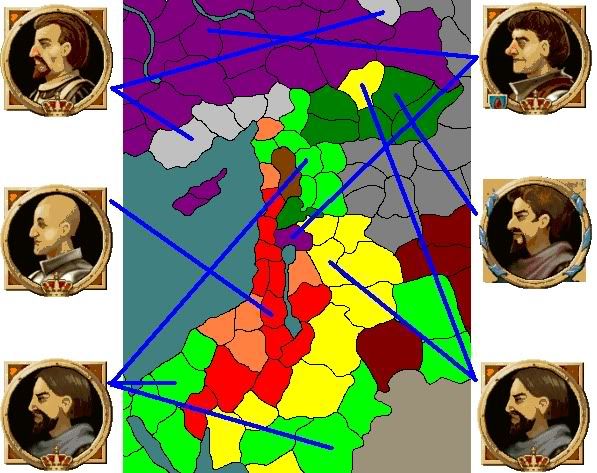

“Anyway, today we’re going to turn to the thirteenth century again, and to 1236 to be precise for that is where we left last Thursday. And as you can see, we’re going to leave the eastern borders of the Empire for a while. For this is a map of the Balkans in the year 1236, or rather, the kingdoms inside the Balkan region. They will be the focus of our attention today. Let’s see who’s around. There’s the Roman Empire of course, in Imperial purple, which need no further introduction. Then there is the Second Bulgar Tsardom, on this map in both shades in blue. Apart from what is shown on this map, they are also the Tsar-Protectors of most of the states of Rus. I’m not going to show a map of that yet, as that’s going to be a nice picture later on, but I must tell you what this title means. As I explained in the first lecture, the Bulgars declared themselves independent in 1186 after Isaakios Angelos forced too much tax on them. They would be led by the house of Asen, who would found the Second Tsardom soon afterwards. When the Kantakouzenoi rise to the Imperial Throne, and Romanion and Bulgaria become allies rather than enemies, the Bulgars start some small wars of conquest in their neighbourhood. These wars eventually lead them into battle with the Cuman, Turkish horse tribes who occupy the plains north of the Black Sea. As the Bulgars continue their crusade, their deeds are heard in the small princely halls of the Russian principalities. And soon, Russian princes seek protection and patronage from the Asens. And slowly but surely, even after the Cuman are defeated, the states of Rus gather behind the golden lion of the Bulgars, who will therefore be able to crown themselves Tsar-Protectors of Rus. And as of such, become one of the most powerful forces in Europe, overshadowing even Hungary and Poland. In fact, only the Roman Empire, and maybe France, Germany and Khwarizmian Persians could raise an army to match that of the Tsar-Protector, Tervel Asen.”

“We will come back to him shortly, but let’s finish the map. In the dark grey, west of Bulgaria, lies the Kingdom of Serbs, ruled by the old king Svetolik of the house of Nemanjic. He will too become important of today’s lecture later on, so remember his name. Finally we have some less important kingdoms – less important for this lecture, mind you – to cover. In dark red is the Kingdom of Bosna, whose territory seems to grow and dwindle with the season due to endless wars with the Serbs and Hungarians. In yellow is the Vlach Kingdom, a tiny mountain realm which has so far managed to remain out of the grasp of both the Bulgars and the Hungarians. And finally there are the Hungarians themselves in light grey and the Germans in olive, major powers but completely irrelevant to today’s story.”

Three portraits appear on the screen

“Now, the troubles start in the summer of 1236. While in Constantinople the old Queen-Regent Prokopios dies from a stroke, the Bulgarian Tsar Terval goes insane. The tsar had been on the throne for nine years already, since he was fifteen years old in fact. But from the start he had been under a lot of stress as he was clearly not made of the same cloth as his father. When he breaks, the world knows it soon enough. He begins insulting courtiers and ambassadors, he walks around the castle naked, and he developed serious signs of schizophrenia. Quite soon his vassals begin to question his ability to rule. As news travels slowly into Rus, the first to split were in fact Bulgarian vassals. They are depicted to the left and the right of this picture here; the elderly widow Desislava Shishman of Vidin, and Terval’s own cousin Ivan, who ruled Karvuna. In fact, Ivan wanted the Bulgarian throne himself, being an Asen and more sane than his cousin. If you remember the map I just showed, the rebellious areas were shown in lighter blue. Soon afterwards the Russian princes followed one by one, and Terval and his loyal generals were faces by the choice of either pacifying the ancestral Bulgarian lands or the distant, stronger Russian realms, with an ever-dwindling army. To illustrate this latter problem, Terval had been able to raise 120.000 men early 1236, while he could muster less than 10.000 two years later. Luckily for Terval and the Bulgarian Tsardom, Roman Emperor Basileios III was both honour- and treatybound to come to his aid.”

“So in the spring of the next year, Emperor Basileios himself rode north with an army of nearly seventeen thousand of Romanion’s finest, originated from Constantinople itself and thus containing the Imperial Bodyguard cataphracts, the Varangian Guard and the Imperial Archers. Within a few months, Basileios managed to conquer the cities of Karvuna and Constantia with little trouble, and managed to bring Ivan Asen to his knees. The principality was returned to Tsar Tarval while the Imperial Army moved west to take another rebellious principality called Dorostorum. The only thing Basileios got from this expedition was another bastard son produced with a Bulgarian lady of high standing whose name has gone lost in history. This boy – aptly named Romanos Boulgarios or Romanos the Younger – was brought into the Imperial Court around the same time Queen Glykeria gave birth to a daughter named Anthusa. And although she had had no problems when Basileios had brough Romanos the Elder to Constantinople, she was clearly very angry when she learned her husband had brought another bastard. It is widely believed that this is when the royal marriage began to break. Eventually, Romanos would be brought to the Athos Monastery to be raised by the monks there, just like his namesake half-brother.”

“In the autumn of 1238, while the Russian princes kept abandoning Terval one by one, revolt also started in the Bulgarian homeland again. This time it was the Despotate of Strymon, led by a six-year old puppet of the local nobility. Strymon had been claimed by the past Emperors for decades as there was a significant Greek majority. It was therefore decided that Strymon would be annexed to the Empire. The new Megas Domestikos Demetrios Meschos would lead the thematoi of Thessalonika against Strymon. Before Strymon would be reached, however, it was reported to Demetrios that also Desislava Shishman of Vidin had renounced her loyalty to the Tsar. Therefore he marched on to Naissus and took the principality of Vidin with little trouble. The Roman Empire had suddenly found herself along the Danube again, and Basileios and the court at Constantinople began to realise that if Tsar Terval might not be able to keep his realm together, it might be a good opportunity to retake some parts of what was lost with the Bulgarian independence fifty years earlier. As of such, Strymon and Vidin, which would be renamed to its ancient name Dardanoi, would become integrated into the Roman Empire as a part of the thema of Thessalonika and a whole new thema respectively.”

“Twice more would Basileios have to invade Karvuna again until it too would submit to him, and become another new thema under the name Mousia. In the same days would Queen Glykeria give birth to a boy who, according to Basileios, certainly could not have been his. The boy, named Demetrios after the Emperor’s father, would be locked away in the Myralaion Monastery and the Queen would be put under careful watch. According to the Emperor, he had not consummated his marriage for at least a year, after he believed Glykeria had been unable to produce him sons. In fact Basileios’ only legitimate son Nikolaos, who was thirteen in 1240, had been the son of Alexandra Argyropoulos. Although Glykeria had given birth to Maximos in 1231, he had been of bad health and had died four years later. Their second child had been a daughter. It was said that Basileios had been… errr… making bastard children to compensate for having only one male heir. The fact that his wife now gave birth to a boy only increasing the bad relationship between the two. From Glykeria’s point of view, her husband was an unfaithful and sexist man, who left her alone in Constantinople for months or even years, and then to return with a bastard son. Not to mention he refused to copulate with her for over a year. The situation eventually escalated when Glykeria was found in bed with an underling of Romanos Argyropoulos named Markos of Herakleia in late May, 1240. Although Markos would only be exiled, Glykeria and Basileios would rarely meet face to face again.”

“With this sad merital crisis in our head, let’s take a little break to get some coffee. The next part is also going to be kind of long, so no more than five, seven minutes. When you return, I’ll tell the conclusion of the collapse of the Bulgarian empire, and about the rise of the Serbian one.”

The coffee break was very hasty. Kalina and me were nearly knocked over by Mrs. Bokova, who came rushing into the lecture hall behind us. Apparently she was late or something. She and professor Doxiadus started talking very busily before the lectern. When the lecture started again after everybody was in, she quickly sat on her seat on the front row. I wondered why she always had to be present, if she didn’t do anything constructive. For some reason I had the feeling she was keeping an eye on the professor.

“Okay, everybody got their coffee? Oh, even Alexios?”

“Right here, professor! I got an Extra Large one.”

Alexios said cheerfully from out of nowhere. I suddenly spotted him on one of the front rows.

“Didn’t you get me one, lad?”

“What…? Oh, no… I’m sorry sir,”

Alexios said, apparently somewhat confused. “But… but you can have this one!”

He held his large paper cup up quite recklessly, and some coffee spilled on the girl next to him.

“Hehe, no that’s okay, I was just joking. Just… go help clean up your neighbour… Anyway…”

The professor gathered his thoughts again. “We left with Basileios’ and Glykeria’s marriage in shambles, although they would never divorce. In the same year, in Bulgaria, the Archbishop of Turnovo turned against Tsar Terval and with him the Bulgarian corelands would be divided to the core. This would effectively break the remaining power of Terval, who would loose his final Russian vassals and see his realm shrink to his crown lands, one loyal count on the north shore of the Danube and a single loyal lord in northern Russia. To add insult to injury, this was when the Serbs decided to attack. The Serbs had been the greatest contester to the Bulgar’s patronage of the Russian princes. In fact, some princes had instead accepted the Serbian king Svetolik Nemanjic as their protector, and this number grew as more princes renounced Terval. The most powerful of these princes was the prince of Kiev, the old Mikhail Rurikovic. Kiev had not been part of the Bulgarian Tsardom, though, but had been independent until swearing loyalty to the Serbs in 1240. In fact, it had been Kiev who single-handedly stopped the Mongol Horde in the 1220’s and for that they were considered the greatest of so-called High Princes. When Serbia and Kiev declared war on both the remains of Bulgaria as well as the Roman Empire, a new chapter of the so-called Balkan Wars.”

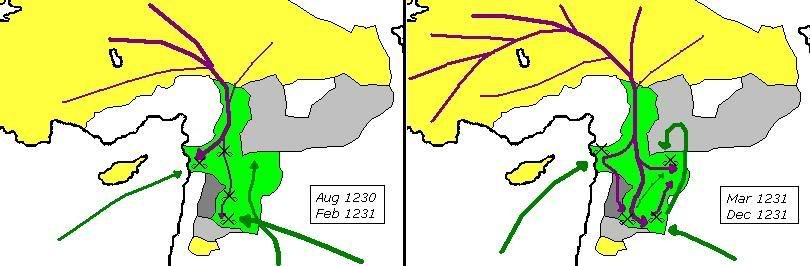

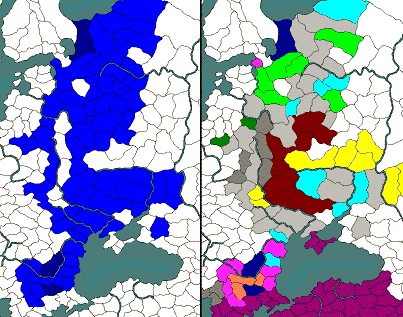

Two maps appeared on the screen. The first one was blue, the second one had all sort of colours.

“First, let’s see what happened to Rus. The first picture shows the Bulgarian domination of Rus. The lighter blue shows the vassals and holdings of Terval Asen in early 1236, the areas in darker blue show what remains of these holdings five years later. I guess you all agree that is pretty impressive, albeit not very pleasant for poor madman Terval. The second map shows what happened to these lost holdings. Purple shows the Empire in 1236, with what was gained from Bulgaria up to 1241 in pink. In the same respect, the dark grey shows the Kingdom of Serbs and her vassals in 1236, and the Russian holdings that sought Serbia’s patronage from 1236 up. You could therefore say the Serbians more or less inherited the title of Tsar-Protector of Rus, although they would never really wield that title. Furthermore, there are the powerful principalities of Ryazan-Novgorod in light green and Muscovy in dark red, and Kiev in yellow although it had not been part of the Bulgar Tsardom. Then there’s the independent Prince-Bishopric of Turnovo in orange, in dark green the areas that would be conquered by Poland and in cyan the remaining independent Russian princes and counts. Finally pay notice to the pink area in the upper left, for that is also part of the Roman Empire. This is the town of Torzhok, home of the strategos of the Peloponessos, Vladimir of Torzhok. Like Safed before the conquest of the Levant, Torzhok was not an integral part of the Empire, but rather a dependant trading post governed by Roman nobility.”

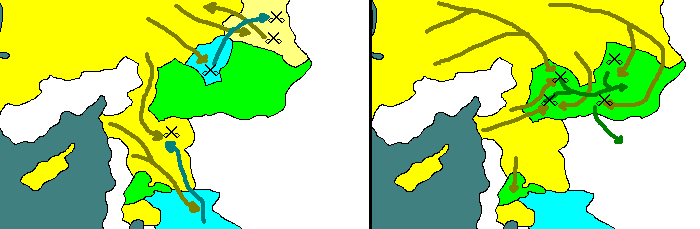

“Anyway, let’s return to King Svetolik of the Serbs. When he declared war on the Empire, he likely did underestimate the size of the Imperial Army. He also believed Basileios would send his army to chase into Rus to fight the Serbs there. And as you all know Rus is a very harsh place for military expeditions. But Basileios had refused to march into Rus to aid Tsar Terval, and was unwilling to do it now. Instead, he focussed his attention to the Serbian homelands just north of the Empire. Again, the thematoi of Thessaloniki would be raised, commanded by the Megas Domestikos Demetrios Meschos. Also, the thematoi of Dyrrachion under the command of strategos Petros Bryennios would be raised, raising the total of Imperial forces to around twelve thousand. While the Megas Domestikos marched to the coast to take the merchant city of Ragousa and the principality of Diokleia, Bryennios and his uncle Andronikos of Ochrid – the father of Queen Glykeria, in fact – went inland to take the Serbian crown lands of Rashka. Although both areas were quickly conquered, King Sverolik himself had fled to his Russian estates. And if they wanted him to surrender, they would have to march into Rus as well. And so, the armies marched through the Balkans towards Rus. Very quickly though, a message arrived at the army that the Megas Domestikos’ mother, Aikatenina Kantakouzenos, had passed away and that Demetrios had to travel to Lykandros to take his family estates. Weakened by the departure of the now former Megas Domestikos and his forces, strategos Petros Bryennios marched on. Meanwhile, however, the Serbian king had met with the armies of his Kievan ally, and both armies marched to Constantinople.”

“The arrival of Serbian and Kievan soldiers before the gates of the Imperial city was a bit of a shock to Basileios. Although the siege that Mikhail of Kiev had laid on the city could be lifted without much trouble, King Sverolik had crossed the Bosporus and marched straight into Anatolia. For three months Basileios and the new Megas Domestikos Isidoros Paleiologos searched for the raiding Serbian army in a wild goose chase. The Megas Domestikos himself became wounded during an attack near Ankyra. Meanwhile, what was left of strategos Bryennios’ army would be destroyed near Smolensk, preventing an easy victory in the Russian heartland. Basileios didn’t want to spend more time and forces against the Rus, and thus would sign a peace treaty with Sverolik himself in Anatolia. In the treaty it was agreed that although Diokleia would become part of the Empire, Rashka would not and Basileios would accept the new Serbian patronage of the Russian princes.”

“Thus began a new period of peace in the Empire, although not before Basileios had the rebellious strategos of Paphragonia, Bartholomaios Kontostephanos murdered and replaced with his two-year old nephew Ignatios Antiohites. Furthermore, Prince Nikolaos, still Basileios’ only legitimate heir, came of age. In a strong political move, it was decided that he would be married to the daughter and oldest child of the King of Armenia, a sixteen year old girl names Alexeia Rubenid. It was Basileios’ hope to see their children become kings of Armenia as well as Roman Emperors, thus finally uniting the two royal houses. Seeing how King Isaakios’ eldest son had just died of pneumonia and his younger son was also of bad health, this was not a far-fetched dream. Basileios sent Nikolaus and Alexeia to Aleppo, where the prince would become a sort of governor of Imperial Syria, as well as the titular bishop of Aleppo. Already in those early days in Aleppo, Nikolaos would reveal himself to be quite a scholar, bringing not only Aleppo and Antioch back to the Christian faith, but also personally or through patronage discovering old works from both Greek and Arab masters. What made Basileios even happier was that Alexeia wore him two sons in those early years; Nikolaus in 1246 and Eleutheros in the next year. Although the young Nikolaus’ health seemed to be somewhat weak, it appeared the Imperial bloodline was secured once more.”

“Well, before I end, I close with the usual, a map of… yes?”

Professor Doxiadus pointed at a female student sitting in one of the front rows, who had raised her hand.

“Sir, what about the Mongols?”

Doxiadus looked a bit confused. “What about them? Do you mean the Il-Khanate?”

“No sir, the Golden Horde. You know, who swept over the Volga plains and the Russian principalities in the 1240’s?”

The professor looked even more confused, upset actually. “What the hell are you talking about, girl? The Golden Horde was defeated by Mikhail of Kiev twenty years earlier. Now, the Il-Khanate…”

“But sir, Professor Bokova told us that it were the Mongols were the masters of Rus, but the Bulgars or Serbs.”

I suddenly heard defiance in the girl’s voice. As well as a Turkish accent. Was she pulling the professor’s leg?

“Well, then she was wrong. No, no more questions,”

professor Doxiadus said resolute. He seemed annoyed, but there was something else. The map appeared on the screen, but he didn’t spend a lot of attention to it.

“You can figure this one out for yourselves, people. That’s it for today… and I’ll see you all Thursday.”

And so the lecture ended. Kalina and I looked at each other, and she shrugged. Then we left the lecture hall together, as the other students also chaotically cleaned up and left. Professor Doxiadus was nowhere to be seen. Just outside the lecture hall, professor Bokova was talking with the Turkish girl who had just asked about the Mongols. She must have been one of Bokova’s students, of course. “Wait, you’re Alexandros Elias, right?”

I turned around. It was Bokova. I mentioned Kalina to walk on – I’d catch up with her. “That’s right, ma’am,”

I said to professor Bokova. “Professor Doxiadus said you were interested in talking with him about your grandfather. And he wonders if you are available next Friday, in the afternoon.” “Sure… but why didn’t he ask me himself?”

Professor Bokova smiled sheepish. “Professor Doxiadus is a very busy man, Alexandros. I help him sometimes, as his personal assistant, I guess.”

Right… his assistant… because she wasn’t the head of the archaeology department… I tried very hard not to roll with my eyes, and instead turned the movement into a nod. “Okay, that’s settled then. He’ll be in his office here at the faculty at four-ish. Oh… and one more thing. Professor Doxiadus has asked me also attend this meeting as I also knew your grandfather. I hope you don’t mind.”

I forced myself to smile and nod, and quickly walked on to catch up with Kalina. I had a bad feeling about this. Very bad indeed.

It wasn't the song I assumed it was going to be though lol (this one)