Chapter 4

The warfare of the Italian Wars, as I said, was an important in the evolution of Western warfare. While tradition weapons likes lances, pikes, halberds, crossbows and swords were still commonplace for the fighting, the Italian Wars marked the beginning of the rapid and large employment of firearms, even if primitive. Matchlock firearms, wheellock pistols, and great artillery pieces were widely used as well, and especially by the French, who loved cannons ever since the weapon’s invention. While personal weapons common of the medieval era were still widely used, and indeed, remained widely used until the onset of the eighteenth century when the final disappearance of pole-arms from infantry formations was completed – the extensive use of firearms and a general, albeit slow to evolve, reliance upon mobility in campaigns became the norm upon which future wars would be fought.

The basic style of fighting in Renaissance Italy was with mass bodied infantry, often in squares, armed with pikes protecting the more exposed musketeers. Matchlock firearms, although deadly at close range, lacked the range of crossbowmen and other archers – at least in terms of their effectiveness and accuracy. Rather than being cut down by the enemy cavalry, it became important to protect these fire-armed units with pike-men and halberd infantry. As for the infantrymen, the majority were equipped with pole-arms, sometimes a shield and sword, and a breastplate of armor for protection. Fighting would often take place between the infantry in brutal hand-to-hand fashion after several volleys of musket fire or arrows. Artillery would be used to pound the enemy infantry into submission, and in the face of breaking, or in retreat, the heavy cavalry would be unleashed to mop up and cause most of the casualties. The key to warfare in the Italian Wars a unique variation of defense, offensive mobility, open fighting to actualize the effectiveness of firearms and cannons, as well as the more ancient but still deadly knights. The old castle defenses of the Middle Ages were otherwise useless, except for the large and “impregnable” city defenses that could hold out much longer than the smaller and isolated castles of the past.

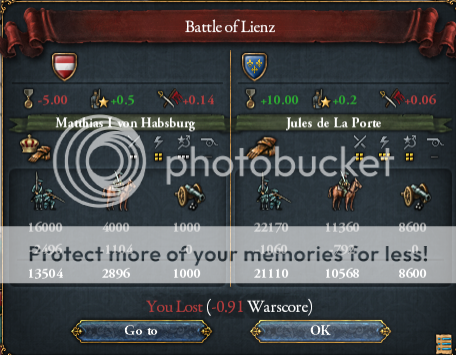

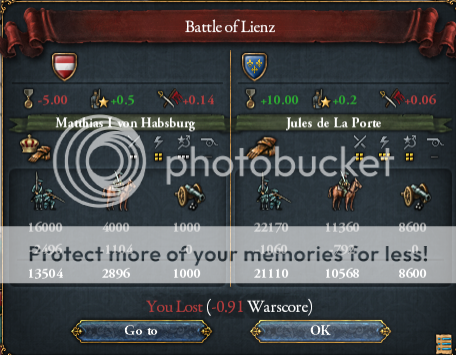

After the battle of Lake Constance, and the abandonment of Milan to the French, the Spring and Summer Campaign in Italy was an absolute disaster for Matthew and the Imperial Army, and that would be putting it nicely. After his victory over Matthew, Duke Jules de la Porte crossed the Austrian Alps into Italy from the north, after defeating Emperor Matthew once more at the Battle of Leinz, with King Louis marching eastward from Milan. They hoped to entrap the fleeing Imperial Army of Italy somewhere in Venice. Venice, which had deceitfully allowed for the Imperial forces to move through their territory, declared war along with Naples, who would come up from the south like a vicious storm. The war was taking shape: France, Provence, Milan, Savoy, Tuscany, Venice, and Naples (the anti-Habsburg Italian alliance, now including France) against the states of the Holy Roman Empire loyal to Matthew – Austria, Hungary, Alsace, the Palatinate, Salzburg (the German States) and the Kingdom of Castile-Aragon.

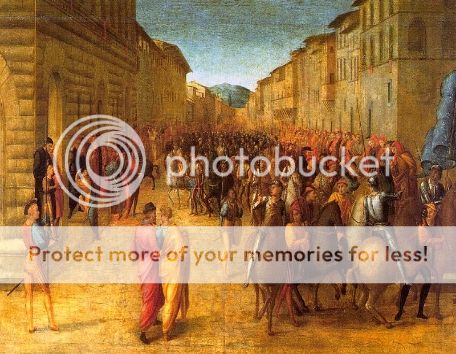

The defeat at Leinz, immediately after the defeat at Lake Constance, meant that the French armies were on the verge of linking up in Italy. Right, an image of French troops passing through an occupied Austrian village.

The French movement early in the war was splendid, and remarkable. Jules de la Porte crossed over the Alps, like Louis, and screamed south. Near Treviso, the Imperial Army of Italy encamped itself, with nearby reinforcements from Hungary and Alsace. Count Leopold Meinl was confident of his defensive position, and wrote back the Matthew that he was gathering the Imperial Army, totaling over 50,000 troops with the allied additions, and prepared to strike back against the French. It is here that the French maneuvering was both a curse and blessing at the same time. Jules de la Porte had not linked up with the advancing Franco-Venetian army under the command of Bernard de Bonnefoy. Bonnefoy, not having expected De la Porte’s rapid movement and crossing of the Alps, had pressed on by three days’ time. The Franco-Venetian Army numbered around 40,000 men, but could have been as high as 70,000 men had they had better communications with De la Porte and had waited a few days for him to arrive and unite. Instead, Bonnefoy was outnumbered.

However, he noticed a problem in the Imperial camp. The Imperial troops, for reasons unknown, had not completely linked up, and were divided at different locations on the field based on ethnicity. At sunrise, 22 July, Bonnefoy launched his attack against the isolated and exposed soldiers from Alsace, commanded by Graf Leopold von Pfasttatt. In the early hours of the morning, the rumbling of French artillery shook the battlefield. Catching the Imperial Army by surprise, Bonnefoy launched a heroic and magnificent cavalry assault on the unsuspecting troops.

“Around daybreak we were ordered to strike the enemy. Many of them were still asleep, and those awake were cooking breakfast. I prayed to the Virgin Mary for protection, but we could hardly believe our luck. With a thunderous roar of our cannons behind us, we galloped forth – about 3,000 of us, bursting down the hill with a loud cry to install fear into the enemy. When we reached the camp, the enemy were disconnected and not ready for combat. We ran over them like flowers on the field. In minutes, the entire camp had been broken, we lost but 30 men in the first minutes of the fighting – causing unmeasurable damage upon our enemy.

After chasing them from the field, we could not believe our luck – truly the Holy Mother was on our side this day. A German artillery camp was spotted, with about 6 cannons limbered and without infantry protection. After chasing off the German troops, we rushed the artillery, taking all six guns captive, along with the artillerists. In the span of less than 30 minutes, we had chased some 4,000 Germans from the field, and captured 6 guns.”

-French Knight’s memoirs of the battle.

The disastrous start to the battle was amended by 8 o’clock. The Imperial Army had formed up and counter-attacked the French positions. Hungarian and Italian soldiers, the Condottieri, had managed to ford the River Sile, and strike the French from the rear. By 9 o’clock, the battle seemed to be turning to Imperial favor. Captain Otto Minucci, an Imperial Condottiero, and the leader of the Imperial Italian mercenaries wrote:

“We crossed the river with the Hungarian cavalry, and took the French and Venetians by surprise. They had not expected us to attack from the rear. He routed the Venetian rearguard, and could see the panic look upon their forces. At that time, some of the men lost their composure. They began screaming and chanting prayers – giving thanks to the Holy Mother for the victory won. De Grunn, [one of the German mercenary captains] had joined with us,but lost control of his men. Believing the battle to be over, they began to loot the French and Venetian treasures back at their camp. I must also confess, I and my men had felt the same spirit.”[1]

For whatever reason, the decision to raid the French camps and rear luggage for loot had terrible consequences for the Imperial Army. The French regrouped, and at noon, launched a vicious counter charge against the Hungarians and Italian condottieri serving in the Imperial Army. Like the charge in the morning, the weight of 5,000 French knights crushed the Imperial forces, which broke and scattered minutes after being struck with the mighty blow. In their hasty flight back across the Sile, several thousands of men drowned in the river while being pursued by the French. The collapse of the Imperial right flank was about to cause a major defeat that could not be afforded.

Realizing that his right flank was about to be enveloped, Meinl order his reserves to the Sile to halt the French attack. This he did, and the French cavalry were repulsed at great loss. However, the decision to pull the reserves to block the French counterattack exposed the Imperial Center. Some 50 French cannons trained all of their attention onto the Imperial Army. By 3 o’clock, the French batteries had pummeled the Imperial center into pieces. Meinl then ordered his men to withdraw by four, using his cavalry to protect the retreating infantry. The Battle of Treviso ended in defeat, and the Imperial forces lost 13,000 men, of which 4,000 were captured. The French and Venetians also suffered heavy casualties, about 15,500. However, the French remained on the field and had forced the expulsion of the Imperial Army from Italy – one of the most remarkable feats in military history in that – in two battles and a few minor engagements, the French had expelled the feared Imperial Army of Italy. With the Imperial Army repulsed from Italy, Louis XIII turned south and captured Ferrera. By the end of August, 1511, in just a matter of months, the Imperial Army had been driven from Italy, and dark clouds over the Habsburg Monarchy had yet to dissipate.

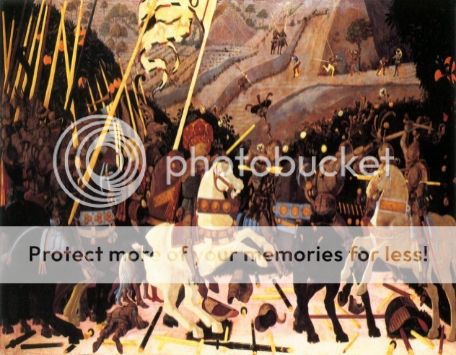

The Battle of Treviso, 22 July 1511 had ended in disaster for the Imperial forces. They were soon to be driven out of Italy by the French. Right, a depiction of the French counter attack at the apex of the battle.

Nearly a month later, just north of same spot where the First Battle of Treviso was fought, Matthew gallantly led a foolish “delaying” action to protect his army of Italy so it could retreat to Istria and recover. Shadowing Jules de le Porte’s army, and hoping to prevent it from countering into Istria, Matthew foolishly gave battle to a superior French army and was promptly routed form the field in a mere matter of hours. Having lost another 6,500 to only 1,800 French, Matthew wrote a nervous letter to his younger brother, Archduke Charles, “I wish to inform you that we have been defeated, alas, crushed. I request your immediate assistance if we are to salvage the situation in Italy.” Archduke Charles was in Moravia, rallying a new army for the 1512 campaign, but it was clear that he might need to leave for Italy understrength just to help save Matthew’s disastrous campaign.

The disastrous Italian Campaign of 1511 had come to an end, and France was the undisputed master of Northern Italy, having driven off the Imperial Army, and routing them in their first three major engagements. However, Louis XIII had to hand over the Italian Campaign to his Italian allies to counter the Castilian invasion of Southern France. At the same time, Leopold von Waldenstein, an elite Austro-German cavalry commander, came to the rescue of the Imperial Army. Taking over commanding from the aging Count Meinl, Waldenstein prepped the troops for the future Campaign of 1512, in which only a small attachment of French soldiers, commanded by the Duke Jules de la Porte, would provide assistance to the Venetian and Neapolitan Army. For Matthew, his hopes of becoming master of Northern Italy had seemingly vanished. Yet, he received the most benevolent Christmas present, a large loan, equivalent to over $4,000,000 (USD) today, from the Medici Bank – bankrolling the rest of the Italian Wars for the Habsburgs.

Fearing that the French would sweep south passed Ferrera, Pope Julius and the Curia had even abandoned Rome and fled into exile, temporarily, into the safe confines of the Monastery of Monte Cassino, where they would remain until the end of the war. Indeed, upon hearing the news that Rome had been abandoned, King Louis led a detachment of his favorite troops into the city – and sacked the city. For the Habsburgs, their defeat in Northern Italy and allowing for the sacking of Rome to happen was a major blow to their prestige in Italy – and as defenders of the Catholic Faith.

[1]Mercenary behavior in battle, like the one I described here, was common place during warfare in Renaissance Italy. Mercenary units were not just hired as part of their payment (that would have been too expensive), instead, they were also promised that they would keep all loot during any of their campaigns. There are many accounts of mercenaries, in the middle of battle, looting the enemy camp instead of continuing the fight. In many cases, the enemy would then regroup and win the day. One of the greatest examples of this behavior was at the Battle of Fornovo, 1495, when Italian mercenaries, fighting the French, decided to raid the French baggage train, allowing French knights to countercharge. In part, that account of Fornovo served as inspiration for the Battle of Treviso.

The warfare of the Italian Wars, as I said, was an important in the evolution of Western warfare. While tradition weapons likes lances, pikes, halberds, crossbows and swords were still commonplace for the fighting, the Italian Wars marked the beginning of the rapid and large employment of firearms, even if primitive. Matchlock firearms, wheellock pistols, and great artillery pieces were widely used as well, and especially by the French, who loved cannons ever since the weapon’s invention. While personal weapons common of the medieval era were still widely used, and indeed, remained widely used until the onset of the eighteenth century when the final disappearance of pole-arms from infantry formations was completed – the extensive use of firearms and a general, albeit slow to evolve, reliance upon mobility in campaigns became the norm upon which future wars would be fought.

The basic style of fighting in Renaissance Italy was with mass bodied infantry, often in squares, armed with pikes protecting the more exposed musketeers. Matchlock firearms, although deadly at close range, lacked the range of crossbowmen and other archers – at least in terms of their effectiveness and accuracy. Rather than being cut down by the enemy cavalry, it became important to protect these fire-armed units with pike-men and halberd infantry. As for the infantrymen, the majority were equipped with pole-arms, sometimes a shield and sword, and a breastplate of armor for protection. Fighting would often take place between the infantry in brutal hand-to-hand fashion after several volleys of musket fire or arrows. Artillery would be used to pound the enemy infantry into submission, and in the face of breaking, or in retreat, the heavy cavalry would be unleashed to mop up and cause most of the casualties. The key to warfare in the Italian Wars a unique variation of defense, offensive mobility, open fighting to actualize the effectiveness of firearms and cannons, as well as the more ancient but still deadly knights. The old castle defenses of the Middle Ages were otherwise useless, except for the large and “impregnable” city defenses that could hold out much longer than the smaller and isolated castles of the past.

After the battle of Lake Constance, and the abandonment of Milan to the French, the Spring and Summer Campaign in Italy was an absolute disaster for Matthew and the Imperial Army, and that would be putting it nicely. After his victory over Matthew, Duke Jules de la Porte crossed the Austrian Alps into Italy from the north, after defeating Emperor Matthew once more at the Battle of Leinz, with King Louis marching eastward from Milan. They hoped to entrap the fleeing Imperial Army of Italy somewhere in Venice. Venice, which had deceitfully allowed for the Imperial forces to move through their territory, declared war along with Naples, who would come up from the south like a vicious storm. The war was taking shape: France, Provence, Milan, Savoy, Tuscany, Venice, and Naples (the anti-Habsburg Italian alliance, now including France) against the states of the Holy Roman Empire loyal to Matthew – Austria, Hungary, Alsace, the Palatinate, Salzburg (the German States) and the Kingdom of Castile-Aragon.

The defeat at Leinz, immediately after the defeat at Lake Constance, meant that the French armies were on the verge of linking up in Italy. Right, an image of French troops passing through an occupied Austrian village.

The French movement early in the war was splendid, and remarkable. Jules de la Porte crossed over the Alps, like Louis, and screamed south. Near Treviso, the Imperial Army of Italy encamped itself, with nearby reinforcements from Hungary and Alsace. Count Leopold Meinl was confident of his defensive position, and wrote back the Matthew that he was gathering the Imperial Army, totaling over 50,000 troops with the allied additions, and prepared to strike back against the French. It is here that the French maneuvering was both a curse and blessing at the same time. Jules de la Porte had not linked up with the advancing Franco-Venetian army under the command of Bernard de Bonnefoy. Bonnefoy, not having expected De la Porte’s rapid movement and crossing of the Alps, had pressed on by three days’ time. The Franco-Venetian Army numbered around 40,000 men, but could have been as high as 70,000 men had they had better communications with De la Porte and had waited a few days for him to arrive and unite. Instead, Bonnefoy was outnumbered.

However, he noticed a problem in the Imperial camp. The Imperial troops, for reasons unknown, had not completely linked up, and were divided at different locations on the field based on ethnicity. At sunrise, 22 July, Bonnefoy launched his attack against the isolated and exposed soldiers from Alsace, commanded by Graf Leopold von Pfasttatt. In the early hours of the morning, the rumbling of French artillery shook the battlefield. Catching the Imperial Army by surprise, Bonnefoy launched a heroic and magnificent cavalry assault on the unsuspecting troops.

“Around daybreak we were ordered to strike the enemy. Many of them were still asleep, and those awake were cooking breakfast. I prayed to the Virgin Mary for protection, but we could hardly believe our luck. With a thunderous roar of our cannons behind us, we galloped forth – about 3,000 of us, bursting down the hill with a loud cry to install fear into the enemy. When we reached the camp, the enemy were disconnected and not ready for combat. We ran over them like flowers on the field. In minutes, the entire camp had been broken, we lost but 30 men in the first minutes of the fighting – causing unmeasurable damage upon our enemy.

After chasing them from the field, we could not believe our luck – truly the Holy Mother was on our side this day. A German artillery camp was spotted, with about 6 cannons limbered and without infantry protection. After chasing off the German troops, we rushed the artillery, taking all six guns captive, along with the artillerists. In the span of less than 30 minutes, we had chased some 4,000 Germans from the field, and captured 6 guns.”

-French Knight’s memoirs of the battle.

The disastrous start to the battle was amended by 8 o’clock. The Imperial Army had formed up and counter-attacked the French positions. Hungarian and Italian soldiers, the Condottieri, had managed to ford the River Sile, and strike the French from the rear. By 9 o’clock, the battle seemed to be turning to Imperial favor. Captain Otto Minucci, an Imperial Condottiero, and the leader of the Imperial Italian mercenaries wrote:

“We crossed the river with the Hungarian cavalry, and took the French and Venetians by surprise. They had not expected us to attack from the rear. He routed the Venetian rearguard, and could see the panic look upon their forces. At that time, some of the men lost their composure. They began screaming and chanting prayers – giving thanks to the Holy Mother for the victory won. De Grunn, [one of the German mercenary captains] had joined with us,but lost control of his men. Believing the battle to be over, they began to loot the French and Venetian treasures back at their camp. I must also confess, I and my men had felt the same spirit.”[1]

For whatever reason, the decision to raid the French camps and rear luggage for loot had terrible consequences for the Imperial Army. The French regrouped, and at noon, launched a vicious counter charge against the Hungarians and Italian condottieri serving in the Imperial Army. Like the charge in the morning, the weight of 5,000 French knights crushed the Imperial forces, which broke and scattered minutes after being struck with the mighty blow. In their hasty flight back across the Sile, several thousands of men drowned in the river while being pursued by the French. The collapse of the Imperial right flank was about to cause a major defeat that could not be afforded.

Realizing that his right flank was about to be enveloped, Meinl order his reserves to the Sile to halt the French attack. This he did, and the French cavalry were repulsed at great loss. However, the decision to pull the reserves to block the French counterattack exposed the Imperial Center. Some 50 French cannons trained all of their attention onto the Imperial Army. By 3 o’clock, the French batteries had pummeled the Imperial center into pieces. Meinl then ordered his men to withdraw by four, using his cavalry to protect the retreating infantry. The Battle of Treviso ended in defeat, and the Imperial forces lost 13,000 men, of which 4,000 were captured. The French and Venetians also suffered heavy casualties, about 15,500. However, the French remained on the field and had forced the expulsion of the Imperial Army from Italy – one of the most remarkable feats in military history in that – in two battles and a few minor engagements, the French had expelled the feared Imperial Army of Italy. With the Imperial Army repulsed from Italy, Louis XIII turned south and captured Ferrera. By the end of August, 1511, in just a matter of months, the Imperial Army had been driven from Italy, and dark clouds over the Habsburg Monarchy had yet to dissipate.

The Battle of Treviso, 22 July 1511 had ended in disaster for the Imperial forces. They were soon to be driven out of Italy by the French. Right, a depiction of the French counter attack at the apex of the battle.

Nearly a month later, just north of same spot where the First Battle of Treviso was fought, Matthew gallantly led a foolish “delaying” action to protect his army of Italy so it could retreat to Istria and recover. Shadowing Jules de le Porte’s army, and hoping to prevent it from countering into Istria, Matthew foolishly gave battle to a superior French army and was promptly routed form the field in a mere matter of hours. Having lost another 6,500 to only 1,800 French, Matthew wrote a nervous letter to his younger brother, Archduke Charles, “I wish to inform you that we have been defeated, alas, crushed. I request your immediate assistance if we are to salvage the situation in Italy.” Archduke Charles was in Moravia, rallying a new army for the 1512 campaign, but it was clear that he might need to leave for Italy understrength just to help save Matthew’s disastrous campaign.

The disastrous Italian Campaign of 1511 had come to an end, and France was the undisputed master of Northern Italy, having driven off the Imperial Army, and routing them in their first three major engagements. However, Louis XIII had to hand over the Italian Campaign to his Italian allies to counter the Castilian invasion of Southern France. At the same time, Leopold von Waldenstein, an elite Austro-German cavalry commander, came to the rescue of the Imperial Army. Taking over commanding from the aging Count Meinl, Waldenstein prepped the troops for the future Campaign of 1512, in which only a small attachment of French soldiers, commanded by the Duke Jules de la Porte, would provide assistance to the Venetian and Neapolitan Army. For Matthew, his hopes of becoming master of Northern Italy had seemingly vanished. Yet, he received the most benevolent Christmas present, a large loan, equivalent to over $4,000,000 (USD) today, from the Medici Bank – bankrolling the rest of the Italian Wars for the Habsburgs.

Fearing that the French would sweep south passed Ferrera, Pope Julius and the Curia had even abandoned Rome and fled into exile, temporarily, into the safe confines of the Monastery of Monte Cassino, where they would remain until the end of the war. Indeed, upon hearing the news that Rome had been abandoned, King Louis led a detachment of his favorite troops into the city – and sacked the city. For the Habsburgs, their defeat in Northern Italy and allowing for the sacking of Rome to happen was a major blow to their prestige in Italy – and as defenders of the Catholic Faith.

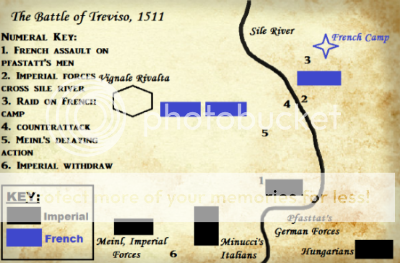

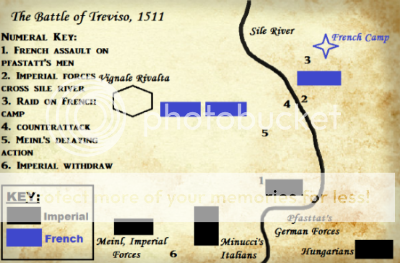

Map 1.1: The Battle of Treviso.

The map was drawn as accurately as possible through MS Paint, using google earth.

The map was drawn as accurately as possible through MS Paint, using google earth.

>>> Continue

[1]Mercenary behavior in battle, like the one I described here, was common place during warfare in Renaissance Italy. Mercenary units were not just hired as part of their payment (that would have been too expensive), instead, they were also promised that they would keep all loot during any of their campaigns. There are many accounts of mercenaries, in the middle of battle, looting the enemy camp instead of continuing the fight. In many cases, the enemy would then regroup and win the day. One of the greatest examples of this behavior was at the Battle of Fornovo, 1495, when Italian mercenaries, fighting the French, decided to raid the French baggage train, allowing French knights to countercharge. In part, that account of Fornovo served as inspiration for the Battle of Treviso.

Last edited: