And once again, religion is the cause of the slaughter of millions. Business as usual.

Religion is hardly the cause of such slaughter. I'm, frankly, tired of hearing this repetitive line over and over. Granted, religion is often used to legitimize violence and adds to war a dimension otherwise not seen (but irreligious fanaticism for political reasons is just as equivalent). I mean, the modern Israeli-Arab conflicts are actually secular in origin (few people bother to note that, and has not been 'going on since the times of the Bible' as many people erroneously belief and report), and only recently has been inclusive of religious language to the conflict -- now that is problem for the peace talks as people claim religious zealotry and attachment to the region which was absent from the conflict from the late 1880s when it began through the 1960s. The Jewish settlers who immigrated through the Aliyah's from the 1880s-1920s were mostly secular, Atheist, and socialist in orientation. The conflict is purely fought over land -- I took 2 courses on the Palestinian and Arab-Israeli conflicts. Much like the Crusades, except for the First, and possibly the Third Crusades, the rest of the Crusades were largely fought for political and prestige purposes. (I plug these since they are often mis-attributed as the 'ideal' case studies of religion and violence).

Contrary to the claims of many talking heads in the media, religion has no more noticeable effect on violence than any other 'secular' or non-religious ideologies. There is much evidence to support a stronger case for religion and nonviolence, e.g. J.K. Kosek "Religion and Non-violence in American History", Jonathan Haidt's The Righteous Mind. Charles Phillips and Alan Axelrod's Encyclopedia of War covers nearly 1800 documented wars/conflicts in human history, and list only 123 as being a religious in conflict orientation and nature. Yeah, the 30 Years' War sticks out like a sore thumb, and so will TTL's equivalent, the 40 Years' War. When religion and violence go hand and hand, it is often far brutal than 'basic' war because of the 'divine' attachment to it. This should be explored, and as I hope to convey with my chapter on the religious character of the war. However I say this not as a 'believer' (Catholic), but as a historian. It's tiresome to hear the same repetitive claims with little historical basis to them. The idea that religion begets 'violence as usual' has little acceptability within mainstream academic scholarship.

Sorry about that, but I just can't let that slip.

Yeah it's hard to get used to playing France in EU4, when frank really perfected the feeling you get as a land major of playing a giant with feet of clay. I just can't get used to how easy it is to be OP as any country (which is partially a product of having idea groups rather than ideas--it's easier as France to say, get trading ideas and become the #1 income player because you're ahead of everything else, whereas in the momod you can't even compete with concentrated trading countries because to do so would make it impossible to compete with the countries with 5 army ideas--I mean I got my ass handed to me by the Saxons because I only had 3 army ideas which would never happen in vanilla EU4)

My wars with France, as Austria, often follow a similar pattern. I just checked their ideas, they have Offensive (complete) and Defensive (6 ideas) not quality. Thus, they're 0.5 ahead in the morale department, with a 10% advantage in discipline too.

Hadn't noticed you had started up another AAR until today, this is one if my favourites yet. Seems the Reformation is spreading surprisingly historically - looking forward to seeing how Austria deals with the coming period.

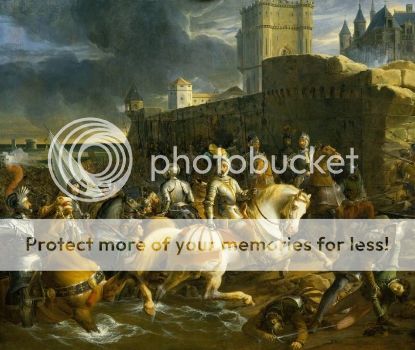

Why thank you for the kind words Tommy! But before we reach the apocalyptic struggle between German Protestantism and German Catholicism (headed by the Habsburgs), and to a lesser extent, due to interventions and alliances, the inclusion of the conflict with the French and Swedes, we still to get through the momentous and just as terrible Italian Wars, which will be the next chapter after I finish the final editing for the last post on the Reformation, laying the groundworks for Chapter 5: The Counter Reformation.

Last edited: